Traditionalist Issues

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Dialogue Mass - CXLII

Ratzinger’s Anti-Scholastic Legacy

Ratzinger was one of the progressivist theologians of the 20th century who sought alternative explanations for the Eucharistic Presence that would enable them to move beyond the strictures of Thomistic Metaphysics so as to satisfy the requirements of the modern world and especially the demands of the Ecumenical Movement. In order to achieve these aims, the perennially valid formulations of the Council of Trent would have to be discarded on the grounds that they are incomprehensible in the world of modern science and “ecumenical fraternity.”

Before looking at Ratzinger’s contribution to aggiornamento in the area of Eucharistic theology, a timely reminder of an almost forgotten papal encyclical is in order – Mysterium Fidei (1965) issued by Paul VI just before the closing of Vatican II. In it, he stated that “it is not permissible … to discuss the mystery of transubstantiation without mentioning what the Council of Trent had to say about the marvellous conversion of the whole substance of the bread into the Body and the whole substance of the wine into the Blood of Christ.” (§ 11)

To illustrate his point about the necessity of using the correct terminology “regarding faith in the most sublime things” he quoted the stern warning of St. Augustine (City of God, X, 23) on this matter:

“But we have to speak in accordance with a fixed rule, so that a lack of restraint in speech on our part may not give rise to some irreverent opinion about the things represented by the words.” (§ 23)

“But we have to speak in accordance with a fixed rule, so that a lack of restraint in speech on our part may not give rise to some irreverent opinion about the things represented by the words.” (§ 23)

The problem for Ratzinger (who claimed to be a devotee of St. Augustine) was that using fixed formulas was not acceptable: he preferred, as we shall see, to let his imagination range freely over ways to describe the “Mystery of Faith” that would appeal to modern man.

Here the wisdom of St. Augustine puts the lie to Vatican II’s false dichotomy between true doctrine and the language in which it is expressed. The correct wording was always considered essential by the Church so as to guarantee the true meaning of transubstantiation, as Mysterium Fidei affirms:

“And so the rule of language which the Church has established through the long labor of centuries, with the help of the Holy Spirit, and which she has confirmed with the authority of the Councils, and which has more than once been the watchword and banner of orthodox faith, is to be religiously preserved, and no one may presume to change it at his own pleasure or under the pretext of new knowledge. Who would ever tolerate that the dogmatic formulas used by the ecumenical councils for the mysteries of the Holy Trinity and the Incarnation be judged as no longer appropriate for men of our times, and let others be rashly substituted for them? In the same way, it cannot be tolerated that any individual should on his own authority take something away from the formulas which were used by the Council of Trent to propose the Eucharistic Mystery for our belief”. (§ 24)

We will now consider to what extent – or whether at all – Ratzinger met the requirements of Mysterium Fidei on the subject of transubstantiation. One might be tempted to think that all is well because he used the term transubstantiation on more than one occasion as, for example in his 2003 book, God is Near Us. 1 How he wanted this to be understood, however, is shrouded in confusion, for only two pages earlier he had referred the reader to Edward Schillebeeckx’s Die Eucharistische Gegenwart (1967) in support of his argument. Schillebeeckx proposed “transignification” – which was specifically condemned by Paul VI in Mysterium Fidei (§ 11) – to replace transubstantiation because he believed that the “ontological dimension … may indeed be open to an interpretation that is different from that of Scholasticism.” 2

Therein lies the rub. The word substance in Scholastic Metaphysics has a different meaning from the same term used in modern physics. So, even when progressivist theologians use the word transubstantiation, there is no guarantee of conformity with Catholic doctrine. In their lexicon it could and often does mean that what changes during the Consecration is not the substance (understood in Scholastic terms) of the bread and wine, but their meaning for the recipient.

Ratzinger took advantage of the development of lexical semantics in modern times to justify getting rid of Aristotelian categories of substance and accidents that had served the Church for centuries, suggesting that they were no longer serviceable:

Ratzinger took advantage of the development of lexical semantics in modern times to justify getting rid of Aristotelian categories of substance and accidents that had served the Church for centuries, suggesting that they were no longer serviceable:

“In the course of the development of philosophical thought and natural sciences, the concept of substance has essentially changed (‘essenzialmente mutato’), as has the conception of what, in Aristotelian thought, had been designated by ‘accident.’ The concept of substance, which had previously been applied to every reality consistent in itself, was increasingly referred to what is physically elusive: to the molecule, to the atom and to elementary particles, and today we know that they too do not represent an ultimate ‘substance,’ but rather a structure of relationships. With this arose a new task for Christian philosophy. The fundamental category of all reality in general terms is no longer substance, but rather relationship.” 3

As is customary with neo-Modernist “explanations,” confusion reigns. The Aristotelian categories belong to the Church’s “perennial philosophy” and have never “essentially changed,” so they are still valid and useful for today and in the future. They remain unaffected by whatever advances are made in the domain of science.

Martin Buber’s Personalism & the ‘theology of relationship’

Ratzinger’s emphasis on a theology of “relationship” rather than of “being” as a means of explaining the nature of God illustrates the dangers of departing from Scholastic Metaphysics. He described God in “personalist” terms as a relationship, but without directing the human intellect to knowing Him as the source of Truth, or the necessity of first bringing our minds in tune with objective reality before we can experience any true relationships with God or one another.

Ratzinger’s emphasis on a theology of “relationship” rather than of “being” as a means of explaining the nature of God illustrates the dangers of departing from Scholastic Metaphysics. He described God in “personalist” terms as a relationship, but without directing the human intellect to knowing Him as the source of Truth, or the necessity of first bringing our minds in tune with objective reality before we can experience any true relationships with God or one another.

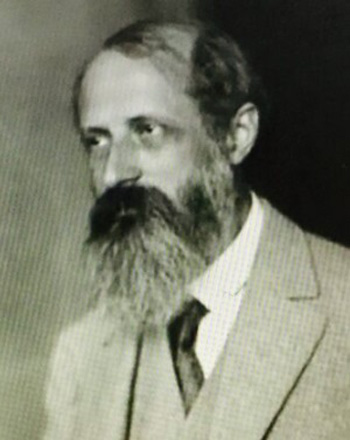

We see here a similarity with the “relationship theory” of the Jewish philosopher, Martin Buber, whom Ratzinger, in his own words, “revered very much … as the great representative of Personalism, the I-Thou principle.” 4 He stated on several occasions that Buber exerted a profound influence on him. Let us examine what kind of influence this was.

Buber was a religious anarchist with utopian ideas for a radical revolution in society along communistic lines. His ideas, transposed to the political sphere, made him hugely popular among Left-wing, liberal Catholics. His great appeal was that he rejected all power-relationships and structures exercising authority in the sense that there should be no moral domination of one person over another. One could say that in some respects Buber’s spiritual anarchism went hand in glove with the Vatican II-inspired image of the “inverted pyramid.” As a result of co-opting Buber’s philosophy of Personalism, Ratzinger allowed socialist and anarchist ideas to infiltrate the Catholic Church.

A new Eucharistic theology

If we were wondering why, whenever Ratzinger broached the question of transubstantiation in his own theological writings, he failed to give an adequate account of the concept as required by Mysterium Fidei, the explanation comes from a firsthand source – his own words:

“We can note with gratitude that in the past century we have been given a new and far-reaching starting point, also from an ecumenical perspective, for an in-depth theology of the Eucharist, which certainly still needs to be further meditated, lived and suffered.” 5 [Emphasis added]

The reference to a new starting point for Eucharistic theology is difficult to square with his previously touted “hermeneutic of continuity,” and is an admission of doctrinal change for the sake of “ecumenism.” It is obvious that this theology did not come from Tradition. His reference to the past century locates the source of the new ideas in the “New Theology” which brought Neo-Modernism into the Church and installed it in a place of honor at Vatican II.

This made it extremely difficult, if not impossible, for anyone who adopted the new Eucharistic theology – and Ratzinger did so, as he said, “with gratitude” – to pass on the Church’s traditional teaching about the Eucharist in a recognizably Catholic way, even if they inwardly accepted it.

For example, in the following passage taken from his book, God Is Near Us, Ratzinger gives the following account of what happens at the Consecration:

“There is something new there that was not before. Knowing about a transformation is part of the most basic Eucharistic faith. Therefore it cannot be the case that the Body of Christ comes to add itself to the bread, as if bread and Body were two similar things that could exist as two ‘substances,’ in the same way, side by side. Whenever the Body of Christ, that is, the risen and bodily Christ, comes, he is greater than the bread, other, not of the same order.

“The transformation happens, which affects the gifts we bring by taking them up into a higher order and changes them, even if we cannot measure what happens. When material things are taken into our body as nourishment, or for that matter whenever any material becomes part of a living organism, it remains the same, and yet as part of a new whole it is itself changed. Something similar happens here. The Lord takes possession of the bread and the wine; he lifts them up, as it were, out of the setting of their normal existence into a new order; even if, from a purely physical point of view, they remain the same, they have become profoundly different.” 6

He stops short, however, of saying exactly in what the difference consists. We can see how he typically advances towards the truth then, as one does in a sailboat, repositions his sails to alter course, tacking backwards and forwards between Catholic and Lutheran positions, but never manages to reach the whole truth. The only certainty that can be gleaned from this mishmash of confused and confusing ideas is that, whatever boat the future Pope was sailing in, it was not the Barque of Peter; he was steering it towards the shoals of “ecumenism” without articulating a coherent account of the central truth of transubstantiation. The reformulation of words in the passage is of the greatest significance. None of the words used by Ratzinger in relation to the Eucharist, such as transubstantiation, transformation, change, conversion etc, is used in a way that has been traditionally understood. They only retain the outer cover of the traditional meanings.

He stops short, however, of saying exactly in what the difference consists. We can see how he typically advances towards the truth then, as one does in a sailboat, repositions his sails to alter course, tacking backwards and forwards between Catholic and Lutheran positions, but never manages to reach the whole truth. The only certainty that can be gleaned from this mishmash of confused and confusing ideas is that, whatever boat the future Pope was sailing in, it was not the Barque of Peter; he was steering it towards the shoals of “ecumenism” without articulating a coherent account of the central truth of transubstantiation. The reformulation of words in the passage is of the greatest significance. None of the words used by Ratzinger in relation to the Eucharist, such as transubstantiation, transformation, change, conversion etc, is used in a way that has been traditionally understood. They only retain the outer cover of the traditional meanings.

This is clearly the case in the following excerpt from a book written by Pope Benedict in his twilight years, which he requested to be published after his death:

“Transubstantiation, not consubstantiation, means transformation, conversio and not just addition. This statement extends far beyond the offerings and fundamentally tells us what Christianity is: it is the transformation of our lives, the transformation of the world as a whole into a new existence.” 7

According to this model which smacks of Teilhardianism and Vatican II’s idea of the Eucharist as the “sacrament of the world,” the emphasis is no longer on the Real Presence but has shifted to the people and their role in transforming themselves and the world.

Continued

Before looking at Ratzinger’s contribution to aggiornamento in the area of Eucharistic theology, a timely reminder of an almost forgotten papal encyclical is in order – Mysterium Fidei (1965) issued by Paul VI just before the closing of Vatican II. In it, he stated that “it is not permissible … to discuss the mystery of transubstantiation without mentioning what the Council of Trent had to say about the marvellous conversion of the whole substance of the bread into the Body and the whole substance of the wine into the Blood of Christ.” (§ 11)

To illustrate his point about the necessity of using the correct terminology “regarding faith in the most sublime things” he quoted the stern warning of St. Augustine (City of God, X, 23) on this matter:

The problem for Ratzinger (who claimed to be a devotee of St. Augustine) was that using fixed formulas was not acceptable: he preferred, as we shall see, to let his imagination range freely over ways to describe the “Mystery of Faith” that would appeal to modern man.

Here the wisdom of St. Augustine puts the lie to Vatican II’s false dichotomy between true doctrine and the language in which it is expressed. The correct wording was always considered essential by the Church so as to guarantee the true meaning of transubstantiation, as Mysterium Fidei affirms:

“And so the rule of language which the Church has established through the long labor of centuries, with the help of the Holy Spirit, and which she has confirmed with the authority of the Councils, and which has more than once been the watchword and banner of orthodox faith, is to be religiously preserved, and no one may presume to change it at his own pleasure or under the pretext of new knowledge. Who would ever tolerate that the dogmatic formulas used by the ecumenical councils for the mysteries of the Holy Trinity and the Incarnation be judged as no longer appropriate for men of our times, and let others be rashly substituted for them? In the same way, it cannot be tolerated that any individual should on his own authority take something away from the formulas which were used by the Council of Trent to propose the Eucharistic Mystery for our belief”. (§ 24)

We will now consider to what extent – or whether at all – Ratzinger met the requirements of Mysterium Fidei on the subject of transubstantiation. One might be tempted to think that all is well because he used the term transubstantiation on more than one occasion as, for example in his 2003 book, God is Near Us. 1 How he wanted this to be understood, however, is shrouded in confusion, for only two pages earlier he had referred the reader to Edward Schillebeeckx’s Die Eucharistische Gegenwart (1967) in support of his argument. Schillebeeckx proposed “transignification” – which was specifically condemned by Paul VI in Mysterium Fidei (§ 11) – to replace transubstantiation because he believed that the “ontological dimension … may indeed be open to an interpretation that is different from that of Scholasticism.” 2

Therein lies the rub. The word substance in Scholastic Metaphysics has a different meaning from the same term used in modern physics. So, even when progressivist theologians use the word transubstantiation, there is no guarantee of conformity with Catholic doctrine. In their lexicon it could and often does mean that what changes during the Consecration is not the substance (understood in Scholastic terms) of the bread and wine, but their meaning for the recipient.

Despite Ratzinger stating a different doctrine, Paul VI made him a Cardinal

“In the course of the development of philosophical thought and natural sciences, the concept of substance has essentially changed (‘essenzialmente mutato’), as has the conception of what, in Aristotelian thought, had been designated by ‘accident.’ The concept of substance, which had previously been applied to every reality consistent in itself, was increasingly referred to what is physically elusive: to the molecule, to the atom and to elementary particles, and today we know that they too do not represent an ultimate ‘substance,’ but rather a structure of relationships. With this arose a new task for Christian philosophy. The fundamental category of all reality in general terms is no longer substance, but rather relationship.” 3

As is customary with neo-Modernist “explanations,” confusion reigns. The Aristotelian categories belong to the Church’s “perennial philosophy” and have never “essentially changed,” so they are still valid and useful for today and in the future. They remain unaffected by whatever advances are made in the domain of science.

Martin Buber’s Personalism & the ‘theology of relationship’

Martin Buber, anarchist & utopian

We see here a similarity with the “relationship theory” of the Jewish philosopher, Martin Buber, whom Ratzinger, in his own words, “revered very much … as the great representative of Personalism, the I-Thou principle.” 4 He stated on several occasions that Buber exerted a profound influence on him. Let us examine what kind of influence this was.

Buber was a religious anarchist with utopian ideas for a radical revolution in society along communistic lines. His ideas, transposed to the political sphere, made him hugely popular among Left-wing, liberal Catholics. His great appeal was that he rejected all power-relationships and structures exercising authority in the sense that there should be no moral domination of one person over another. One could say that in some respects Buber’s spiritual anarchism went hand in glove with the Vatican II-inspired image of the “inverted pyramid.” As a result of co-opting Buber’s philosophy of Personalism, Ratzinger allowed socialist and anarchist ideas to infiltrate the Catholic Church.

A new Eucharistic theology

If we were wondering why, whenever Ratzinger broached the question of transubstantiation in his own theological writings, he failed to give an adequate account of the concept as required by Mysterium Fidei, the explanation comes from a firsthand source – his own words:

“We can note with gratitude that in the past century we have been given a new and far-reaching starting point, also from an ecumenical perspective, for an in-depth theology of the Eucharist, which certainly still needs to be further meditated, lived and suffered.” 5 [Emphasis added]

The reference to a new starting point for Eucharistic theology is difficult to square with his previously touted “hermeneutic of continuity,” and is an admission of doctrinal change for the sake of “ecumenism.” It is obvious that this theology did not come from Tradition. His reference to the past century locates the source of the new ideas in the “New Theology” which brought Neo-Modernism into the Church and installed it in a place of honor at Vatican II.

This made it extremely difficult, if not impossible, for anyone who adopted the new Eucharistic theology – and Ratzinger did so, as he said, “with gratitude” – to pass on the Church’s traditional teaching about the Eucharist in a recognizably Catholic way, even if they inwardly accepted it.

For example, in the following passage taken from his book, God Is Near Us, Ratzinger gives the following account of what happens at the Consecration:

“There is something new there that was not before. Knowing about a transformation is part of the most basic Eucharistic faith. Therefore it cannot be the case that the Body of Christ comes to add itself to the bread, as if bread and Body were two similar things that could exist as two ‘substances,’ in the same way, side by side. Whenever the Body of Christ, that is, the risen and bodily Christ, comes, he is greater than the bread, other, not of the same order.

“The transformation happens, which affects the gifts we bring by taking them up into a higher order and changes them, even if we cannot measure what happens. When material things are taken into our body as nourishment, or for that matter whenever any material becomes part of a living organism, it remains the same, and yet as part of a new whole it is itself changed. Something similar happens here. The Lord takes possession of the bread and the wine; he lifts them up, as it were, out of the setting of their normal existence into a new order; even if, from a purely physical point of view, they remain the same, they have become profoundly different.” 6

Ratzinger’s God is Near Us blends Lutheranism with Catholicism

This is clearly the case in the following excerpt from a book written by Pope Benedict in his twilight years, which he requested to be published after his death:

“Transubstantiation, not consubstantiation, means transformation, conversio and not just addition. This statement extends far beyond the offerings and fundamentally tells us what Christianity is: it is the transformation of our lives, the transformation of the world as a whole into a new existence.” 7

According to this model which smacks of Teilhardianism and Vatican II’s idea of the Eucharist as the “sacrament of the world,” the emphasis is no longer on the Real Presence but has shifted to the people and their role in transforming themselves and the world.

Continued

- J. Ratzinger, God Is Near Us, San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 2003, p. 87.

- Edward Schillebeeckx, The Eucharist, New York: Sheed and Ward, 1968, p. 84.

- Benedict XVI, Che Cos’è il Cristianesimo?, p. 130 (online version)

- Benedict XVI, Last Testament, p. 99.

- Benedict XVI, Che Cos’è il Cristianesimo?, p. 133.

- J. Ratzinger, God Is Near Us, p.86.

- Benedict XVI, Che Cos’è il Cristianesimo?, p. 132.

Posted August 13, 2024

______________________

______________________

Volume I |

Volume II |

Volume III |

Volume IV |

Volume V |

Volume VI |

Volume VII |

Volume VIII |

Volume IX |

Volume X |

Volume XI |

Special Edition |