Traditionalist Issues

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Dialogue Mass - XLVI

A ‘Crazy Patchwork’ of Incongruous Elements

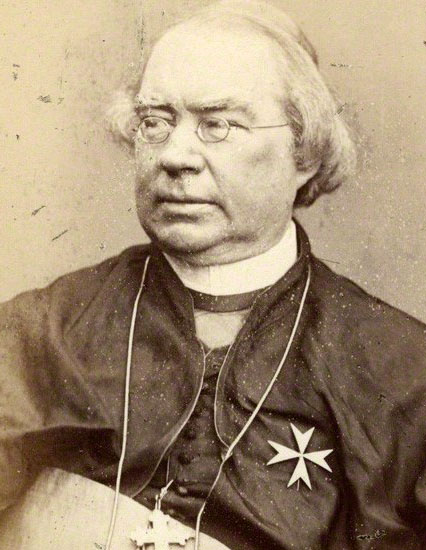

The 19th century Cardinal Archbishop of Westminster, Nicholas Wiseman, has shown how the Holy Week services were “an aggregate of religious observances, gradually framed in the Church, not by a cold and formal enactment, but by the fervid manifestations of the devout impressions of every age, till they have acquired a uniform, consistent and compact form.” (1)

That was, of course, how the liturgy was formed in the early centuries until it reached a stage of such excellence as to be codified in that form by Pope Pius V. But it was otherwise with Pius XII whose “cold and formal enactment” of 16 November 1955 destroyed rites that have long been understood as the very heart and centre of the Church’s year.

That was, of course, how the liturgy was formed in the early centuries until it reached a stage of such excellence as to be codified in that form by Pope Pius V. But it was otherwise with Pius XII whose “cold and formal enactment” of 16 November 1955 destroyed rites that have long been understood as the very heart and centre of the Church’s year.

“In attending them,” Card. Wiseman assured the faithful, “you may consider yourselves as led by turns to every period of religious antiquity … the same spirit has presided over the institution of them all. To abolish them, to substitute a new, systematic, formal and coldly meditated form, would be in truth a vandalism, a religious barbarism, of which the Catholic Church is quite incapable.” (2)

Who would have thought that in the very next century after His Eminence had spoken those fateful words, there would be Popes, starting with Pius XII, who proved quite capable of earning that shameful reputation in History?

Palm Sunday was only the opening gambit

The progressivist reformers did not limit their depredations to Palm Sunday. Their policy of cutting out traditional prayers and ceremonies and sewing on alien pieces turned the rest of Holy Week into a “crazy patchwork” of incongruous elements guaranteed to destroy the continuity and harmony of the traditional rites.

As we shall see from the evidence below, all the “cuts” had the effect of:

It is clear that these prototypes were the practical outcome of a coherent, integrated set of principles developed by the progressivists to achieve the above-mentioned effects. But we must note that they did not apply them comprehensively to the Holy Week liturgy, but rather in a piecemeal fashion, and sometimes only as an option, so as not to provoke too strong a reaction from the faithful and, so, endanger the future reforms that they had envisaged.

Let us consider some examples taken from the Triduum ceremonies of Holy Thursday, Good Friday and Holy Saturday:

The mandatum or foot-washing ceremony

Now, we come to a reform which did not arise spontaneously from the devotion of the people, and which nobody except the progressivists wanted and, certainly, no one requested or needed. Pius XII introduced a ceremony that had no precedent in the History of the Church: the washing of the feet of laymen during the Mass of Holy Thursday.

What is most disturbing about this innovation is that it originated from the most extreme wing of the Liturgical Movement, as Fr. Hermann Schmidt S.J., Professor of Liturgy at the Gregorianum, Rome, candidly admitted:

What is most disturbing about this innovation is that it originated from the most extreme wing of the Liturgical Movement, as Fr. Hermann Schmidt S.J., Professor of Liturgy at the Gregorianum, Rome, candidly admitted:

“It was during the Liturgical Congress at Lugano in 1953 that we proposed, not without opposition, putting the foot washing after the chanting of the Gospel at Mass. … It is a new evolution in the history of the mandatum. (3) [emphasis added]

The rubrics state that this can take place in the sanctuary (“in medio presbyterii”) after the homily. This is in marked contrast to the rubrics of the pre-1955 Missale Romanum, which stipulated that after the stripping of the altars, the clergy gathered together for the foot washing ceremony (conveniunt Clerici ad faciendum Mandatum). This was to take place in a specially designated area (in loco ad id deputato), which was usually a chapter house or a priest’s residence or a different part of the church building where the ceremony could be performed in privacy and without the participation of laymen.

The first point to note about Pius XII’s innovation is the cacophony of symbols it presents. In fact, when viewed against the backdrop of liturgical tradition, the whole ceremony abounds in anomaly.

This was the first papally sanctioned use of the sanctuary for the purposes of “active participation” by the laity. It may have seemed a small concession in 1955 and few people, then, realized the threat such an innovation posed to the priesthood. But History has shown that it acted as a snowball that gathered an unstoppable momentum until, with the proliferation of lay ministries in the liturgy in the 1970s, it completely submerged the uniqueness of the priesthood.

Clericalizing the laity

Theologically, there ensued some adverse results, which could have been foreseen and avoided. By giving lay people privileges to enter the sanctuary and therein perform liturgical functions hitherto reserved for the clergy, Pius XII opened the way to undermining the role of the ordained ministers.

It was inevitable that the effect of this radical innovation would not only blur the distinction between the priest and the non-ordained members of the Church, but also create confusion over the architectural expression of that distinction: the sanctuary for the clergy and the nave for the people. And it is equally obvious that this weakened concept of the priesthood would, in turn, lead to the re-ordering of churches or the building of new ones to express the “new theology” that exalted the laity and diminished the role of the priest.

In short, the reformed Holy Thursday rite fails to invoke the spiritual connections that were inherent in the traditional liturgy and its supporting architecture, both of which helped reinforce what the priesthood means. It is also clear that this particular reform went hand in hand with the progressivists’ revolutionary ideas of what a church is, how it should function and what message it should proclaim: the democratization of the People of God.

Continued

Card. Wiseman warned against abolishing the liturgical customs of the ages

“In attending them,” Card. Wiseman assured the faithful, “you may consider yourselves as led by turns to every period of religious antiquity … the same spirit has presided over the institution of them all. To abolish them, to substitute a new, systematic, formal and coldly meditated form, would be in truth a vandalism, a religious barbarism, of which the Catholic Church is quite incapable.” (2)

Who would have thought that in the very next century after His Eminence had spoken those fateful words, there would be Popes, starting with Pius XII, who proved quite capable of earning that shameful reputation in History?

Palm Sunday was only the opening gambit

The progressivist reformers did not limit their depredations to Palm Sunday. Their policy of cutting out traditional prayers and ceremonies and sewing on alien pieces turned the rest of Holy Week into a “crazy patchwork” of incongruous elements guaranteed to destroy the continuity and harmony of the traditional rites.

As we shall see from the evidence below, all the “cuts” had the effect of:

- Reducing the solemnity of the rites and the honor due to God;

- Obscuring some doctrines of the Faith;

- Minimizing the status of the priest;

- Depriving the Holy Week liturgy of some of its linguistic and musical heritage.

- Promoting the self-fulfilment of the laity through “active participation;”

- Downgrading the liturgy to meet that alleged need.

It is clear that these prototypes were the practical outcome of a coherent, integrated set of principles developed by the progressivists to achieve the above-mentioned effects. But we must note that they did not apply them comprehensively to the Holy Week liturgy, but rather in a piecemeal fashion, and sometimes only as an option, so as not to provoke too strong a reaction from the faithful and, so, endanger the future reforms that they had envisaged.

Let us consider some examples taken from the Triduum ceremonies of Holy Thursday, Good Friday and Holy Saturday:

The mandatum or foot-washing ceremony

Now, we come to a reform which did not arise spontaneously from the devotion of the people, and which nobody except the progressivists wanted and, certainly, no one requested or needed. Pius XII introduced a ceremony that had no precedent in the History of the Church: the washing of the feet of laymen during the Mass of Holy Thursday.

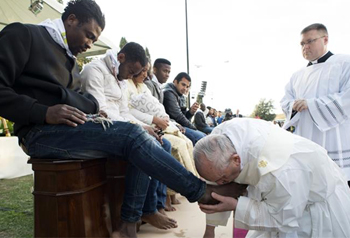

The mandatum was traditionally for clerics, a reflection of Christ washing the feet of the Apostles. After many abuses we see, below, Francis washing the feet of Muslim & Hindu male & female refugees

“It was during the Liturgical Congress at Lugano in 1953 that we proposed, not without opposition, putting the foot washing after the chanting of the Gospel at Mass. … It is a new evolution in the history of the mandatum. (3) [emphasis added]

The rubrics state that this can take place in the sanctuary (“in medio presbyterii”) after the homily. This is in marked contrast to the rubrics of the pre-1955 Missale Romanum, which stipulated that after the stripping of the altars, the clergy gathered together for the foot washing ceremony (conveniunt Clerici ad faciendum Mandatum). This was to take place in a specially designated area (in loco ad id deputato), which was usually a chapter house or a priest’s residence or a different part of the church building where the ceremony could be performed in privacy and without the participation of laymen.

The first point to note about Pius XII’s innovation is the cacophony of symbols it presents. In fact, when viewed against the backdrop of liturgical tradition, the whole ceremony abounds in anomaly.

This was the first papally sanctioned use of the sanctuary for the purposes of “active participation” by the laity. It may have seemed a small concession in 1955 and few people, then, realized the threat such an innovation posed to the priesthood. But History has shown that it acted as a snowball that gathered an unstoppable momentum until, with the proliferation of lay ministries in the liturgy in the 1970s, it completely submerged the uniqueness of the priesthood.

Clericalizing the laity

Theologically, there ensued some adverse results, which could have been foreseen and avoided. By giving lay people privileges to enter the sanctuary and therein perform liturgical functions hitherto reserved for the clergy, Pius XII opened the way to undermining the role of the ordained ministers.

It was inevitable that the effect of this radical innovation would not only blur the distinction between the priest and the non-ordained members of the Church, but also create confusion over the architectural expression of that distinction: the sanctuary for the clergy and the nave for the people. And it is equally obvious that this weakened concept of the priesthood would, in turn, lead to the re-ordering of churches or the building of new ones to express the “new theology” that exalted the laity and diminished the role of the priest.

In short, the reformed Holy Thursday rite fails to invoke the spiritual connections that were inherent in the traditional liturgy and its supporting architecture, both of which helped reinforce what the priesthood means. It is also clear that this particular reform went hand in hand with the progressivists’ revolutionary ideas of what a church is, how it should function and what message it should proclaim: the democratization of the People of God.

Continued

- Nicholas Wiseman, Four lectures on the offices and ceremonies of Holy Week, as performed in the Papal chapels delivered in Rome in the Lent of 1837, London: C. Dolman, 1839, p. 145.

- Ibid., p. 146.

- H. Schmidt S.J. (ed.), Hebdomada Sancta, 2 vols., Rome: Herder, 1956-1957, vol. 2, p. 775.

Posted February 27, 2017

______________________

______________________

Volume I |

Volume II |

Volume III |

Volume IV |

Volume V |

Volume VI |

Volume VII |

Volume VIII |

Volume IX |

Volume X |

Volume XI |

Special Edition |