Traditionalist Issues

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Dialogue Mass - XIII

The Appeasement Process:

Feeding the German Crocodile (1)

In the previous article, we have seen how papal authority was in ignominious retreat before the aggression of the German liturgists whose goals lay far beyond the limits of any reasonable accommodation. The seriousness of the German Bishops’ 1943 challenge can be seen as the first of a series of challenges, each one of which carried with it an extra nail in the coffin of Catholic Tradition, culminating in the reforms of Vatican II.

For what they were contemplating were changes in the millennial rites, starting with the Easter Vigil, to adapt them to the spirit of modern times. The loss of Latin and the destruction of the treasury of sacred music were also part and parcel of the whole plan. (Bugnini would certainly see to that.)

Confronted with an increasingly menacing international situation of anti-Roman hostility and wishing to avoid open conflict, Pope Pius XII adopted a conciliatory approach to the demands of liturgical reformers. His message to the German Episcopal Conference in 1943 was tantamount to saying: Continue breaking liturgical law and the Holy See will reward you with its prize of papal approval.

Confronted with an increasingly menacing international situation of anti-Roman hostility and wishing to avoid open conflict, Pope Pius XII adopted a conciliatory approach to the demands of liturgical reformers. His message to the German Episcopal Conference in 1943 was tantamount to saying: Continue breaking liturgical law and the Holy See will reward you with its prize of papal approval.

It must be admitted that an overwhelming preponderance of evidence pointed to the futility of appeasement well before this date. With the rise of the Liturgical Movement in the Benedictine Abbey of Maria Laach in Germany in 1914 and the pioneering work of Fr. Pius Parsch in Austria in 1918, liturgical anarchy and ecumenical contacts were flourishing with impunity in the German-speaking lands.

No amount of concessionary favors from the Holy See could have assuaged the hunger of the beast of reform: The German crocodile (1) was not content with a few scraps thrown in its direction. As everyone knows, crocodilians are predators with insatiable appetites.

Mediator Dei: a compromise document

A careful reading shows that Mediator Dei (1947) is a “political” document which takes both sides of the debate, so that reformers and traditionalists can find support for their point of view and argue endlessly over which side best represents the thinking of the Pope.

It is true that Pius XII reprimanded various liturgical abuses, but in the same document he also gave the reformers room to move, to make progress on their agenda of “active participation.” Most dismayingly of all for traditionalists, he praised the party of reform and demonstrated his commitment to the Liturgical Movement with these words:

“The movement owed its rise to commendable private initiative and more particularly to the zealous and persistent labor of several monasteries within the distinguished Order of Saint Benedict.” (2) And, “We derive no little satisfaction from the wholesome results of the movement just described.” (3)

Misplaced praise for a misbegotten movement

But was the outcome really so splendid? And were the liturgical leaders so admirable? To answer yes would be historically inaccurate and intellectually incoherent.

By 1947, the new breed of Biblical scholars, theologians and liturgists had been engaged in liturgical experimentation on their own initiative for decades.(4) They had also succeeded, largely unmolested by ecclesiastical hierarchy, in propagating their revolutionary agenda in books, reviews, lectures, liturgical centers, study weeks and conferences.

By 1947, the new breed of Biblical scholars, theologians and liturgists had been engaged in liturgical experimentation on their own initiative for decades.(4) They had also succeeded, largely unmolested by ecclesiastical hierarchy, in propagating their revolutionary agenda in books, reviews, lectures, liturgical centers, study weeks and conferences.

And it was from the Benedictine monasteries that these “new ideas” first spread to country after country around the world, with the towering figure of Dom Lambert Beauduin presiding over the movement like a brooding colossus. (5)

Pius XII seemed to be suggesting that the Liturgical Movement, purged of its abuses, was praiseworthy. That is the same argument used today in relation to the Novus Ordo. But, there could be no good outcomes, no “wholesome results” from reforms that were not rooted in the faith and tradition of the Church. (6)

Besides, it is only the merest fancy that there existed a liturgical “movement” before Beauduin appeared on the scene to claim that he was fulfilling the aims of Pope Pius X. Wherever the Catholic faith flourished, this was due to sound catechesis and the correct spirit and practice of the liturgy as taught by Pius X, who never considered himself part of anyone’s “movement.”

If we join the dots, the full picture emerges

There is a general reluctance among traditionalists to acknowledge that the liturgical reforms of Pius XII are part of a continuum from the inception of the Liturgical Movement in 1909 at the Benedictine Abbey of Mont-César to the creation of the Novus Ordo 60 years later. Yet these were the words of Paul VI when he promulgated the New Mass on April 3, 1969:

“It was felt necessary to revise and enrich the formulae of the Roman Missal. The first stage of such a reform was the work of Our Predecessor Pius XII with the reform of the Easter Vigil and the rites of Holy Week, which constituted the first step in the adaptation of the Roman Missal to the contemporary way of thinking.” (7)

It is not without significance that a future Abbot Primate of the Benedictine Order, Dom Rembert Weakland, who inherited the avant-garde ideas of Beauduin’s Liturgical Movement, would be one of Paul VI’s personal consultors with regard to the Novus Ordo. (8) This demonstrates that the official reforms of Pius XII, no less than those of Paul VI, were tarred with the same brush, tainted from their Benedictine sources.

It follows that Pacelli and Montini must bear the ultimate responsibility – each in his own way – for the unprecedented changes to the Roman Rite that they signed into law.

It follows that Pacelli and Montini must bear the ultimate responsibility – each in his own way – for the unprecedented changes to the Roman Rite that they signed into law.

Liturgical anarchy

In the early part of the 20th century, unauthorized liturgical experimentation was conducted in secret, among a select few, in the crypt of Maria Laach Abbey, at monastic retreats, in university chaplaincies and societies of youth groups, among soldiers on active duty during World War I, on seafaring missions or among radical groups such as The Catholic Worker.

Subversive ideas were spread in samizdat publications distributed from hand to hand or by word of mouth in small-scale conferences held behind closed doors.

But by 1940, the movement gradually spread around the world into parishes with the open or tacit approval of Bishops, who were won over in increasing numbers to the “new ideas.”

Let us not forget that this was Beauduin’s original stratagem. He had a clear, long-term goal in mind as cynical as it was malicious – to win support from Bishops and Prelates so that his revolutionary agenda would be imposed by “legitimate” authority, (9) (see here, p. 21) while the practice of traditional Catholicism would one day be turned into a prohibited activity by the same authorities. Prophetic, demonic or what?

But what about Pius XII’s criticisms in Mediator Dei of liturgical abuses and the faulty theology that inspired them? As these mildly expressed rebukes did not reveal a resolve to deal appropriately with the offenders (who either ignored or denied them), they were taken to be a display of weakness – as if to say the Church did not take too seriously her own liturgical laws.

Mediator Dei thus sent a clear signal of supine capitulation and, further, an invitation to side-step the system. (Bugnini would later boast that the incredible success of the reformers vindicated the adage that “Fortune favors the brave.”) (10)

The ease with which the reformers could get away with breaking the law was a huge incentive behind the Liturgical Movement. In the absence of tough-minded measures against the dissidents, it became clear to them that the possibility of a far more drastic reform of the liturgy was being opened up under Pius XII than had hitherto been dreamed of.

In fact, as we shall see in the next article, the 10 years following Mediator Dei saw the Pope steadily succumbing to their demands and entrenching some of their reforms in the Church’s liturgy. They would soon gain everything they had been fighting for, and much more besides, after Vatican II.

It was Pius XII’s profound ambivalence that made effective control of the Liturgical Movement impossible. Whose side was he really on? Opposing factions claimed victory.

But the claim for the traditionalist party rang hollow when they found themselves abandoned to the tender mercies of Bugnini who was given the executive role on the 1948 Commission for the General Reform of the Liturgy by none other than Pius XII himself.

Continued

For what they were contemplating were changes in the millennial rites, starting with the Easter Vigil, to adapt them to the spirit of modern times. The loss of Latin and the destruction of the treasury of sacred music were also part and parcel of the whole plan. (Bugnini would certainly see to that.)

Fr. Pius Parsch was a pioneer of liturgical reforms and ecumenical contacts

It must be admitted that an overwhelming preponderance of evidence pointed to the futility of appeasement well before this date. With the rise of the Liturgical Movement in the Benedictine Abbey of Maria Laach in Germany in 1914 and the pioneering work of Fr. Pius Parsch in Austria in 1918, liturgical anarchy and ecumenical contacts were flourishing with impunity in the German-speaking lands.

No amount of concessionary favors from the Holy See could have assuaged the hunger of the beast of reform: The German crocodile (1) was not content with a few scraps thrown in its direction. As everyone knows, crocodilians are predators with insatiable appetites.

Mediator Dei: a compromise document

A careful reading shows that Mediator Dei (1947) is a “political” document which takes both sides of the debate, so that reformers and traditionalists can find support for their point of view and argue endlessly over which side best represents the thinking of the Pope.

It is true that Pius XII reprimanded various liturgical abuses, but in the same document he also gave the reformers room to move, to make progress on their agenda of “active participation.” Most dismayingly of all for traditionalists, he praised the party of reform and demonstrated his commitment to the Liturgical Movement with these words:

“The movement owed its rise to commendable private initiative and more particularly to the zealous and persistent labor of several monasteries within the distinguished Order of Saint Benedict.” (2) And, “We derive no little satisfaction from the wholesome results of the movement just described.” (3)

Misplaced praise for a misbegotten movement

But was the outcome really so splendid? And were the liturgical leaders so admirable? To answer yes would be historically inaccurate and intellectually incoherent.

Dom Beauduin presided over the liturgical movement like a brooding Appennine Colossus

And it was from the Benedictine monasteries that these “new ideas” first spread to country after country around the world, with the towering figure of Dom Lambert Beauduin presiding over the movement like a brooding colossus. (5)

Pius XII seemed to be suggesting that the Liturgical Movement, purged of its abuses, was praiseworthy. That is the same argument used today in relation to the Novus Ordo. But, there could be no good outcomes, no “wholesome results” from reforms that were not rooted in the faith and tradition of the Church. (6)

Besides, it is only the merest fancy that there existed a liturgical “movement” before Beauduin appeared on the scene to claim that he was fulfilling the aims of Pope Pius X. Wherever the Catholic faith flourished, this was due to sound catechesis and the correct spirit and practice of the liturgy as taught by Pius X, who never considered himself part of anyone’s “movement.”

If we join the dots, the full picture emerges

There is a general reluctance among traditionalists to acknowledge that the liturgical reforms of Pius XII are part of a continuum from the inception of the Liturgical Movement in 1909 at the Benedictine Abbey of Mont-César to the creation of the Novus Ordo 60 years later. Yet these were the words of Paul VI when he promulgated the New Mass on April 3, 1969:

“It was felt necessary to revise and enrich the formulae of the Roman Missal. The first stage of such a reform was the work of Our Predecessor Pius XII with the reform of the Easter Vigil and the rites of Holy Week, which constituted the first step in the adaptation of the Roman Missal to the contemporary way of thinking.” (7)

It is not without significance that a future Abbot Primate of the Benedictine Order, Dom Rembert Weakland, who inherited the avant-garde ideas of Beauduin’s Liturgical Movement, would be one of Paul VI’s personal consultors with regard to the Novus Ordo. (8) This demonstrates that the official reforms of Pius XII, no less than those of Paul VI, were tarred with the same brush, tainted from their Benedictine sources.

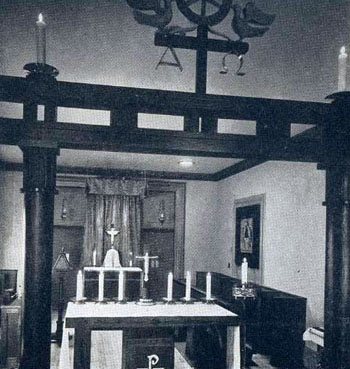

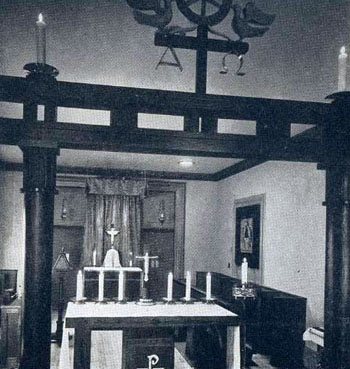

In the U.S. the liturgical reforms were also applied in the 1940s: above, St. Francis of Assisi Church in Portland, OR, and Little Flower Shrine in Royal Oak, MI; below, St. Paul's Priory Chapel in Keyport, NJ, and St. Mark's Church in Burlington, VT

Liturgical anarchy

In the early part of the 20th century, unauthorized liturgical experimentation was conducted in secret, among a select few, in the crypt of Maria Laach Abbey, at monastic retreats, in university chaplaincies and societies of youth groups, among soldiers on active duty during World War I, on seafaring missions or among radical groups such as The Catholic Worker.

Subversive ideas were spread in samizdat publications distributed from hand to hand or by word of mouth in small-scale conferences held behind closed doors.

But by 1940, the movement gradually spread around the world into parishes with the open or tacit approval of Bishops, who were won over in increasing numbers to the “new ideas.”

Let us not forget that this was Beauduin’s original stratagem. He had a clear, long-term goal in mind as cynical as it was malicious – to win support from Bishops and Prelates so that his revolutionary agenda would be imposed by “legitimate” authority, (9) (see here, p. 21) while the practice of traditional Catholicism would one day be turned into a prohibited activity by the same authorities. Prophetic, demonic or what?

But what about Pius XII’s criticisms in Mediator Dei of liturgical abuses and the faulty theology that inspired them? As these mildly expressed rebukes did not reveal a resolve to deal appropriately with the offenders (who either ignored or denied them), they were taken to be a display of weakness – as if to say the Church did not take too seriously her own liturgical laws.

Mediator Dei thus sent a clear signal of supine capitulation and, further, an invitation to side-step the system. (Bugnini would later boast that the incredible success of the reformers vindicated the adage that “Fortune favors the brave.”) (10)

The ease with which the reformers could get away with breaking the law was a huge incentive behind the Liturgical Movement. In the absence of tough-minded measures against the dissidents, it became clear to them that the possibility of a far more drastic reform of the liturgy was being opened up under Pius XII than had hitherto been dreamed of.

In fact, as we shall see in the next article, the 10 years following Mediator Dei saw the Pope steadily succumbing to their demands and entrenching some of their reforms in the Church’s liturgy. They would soon gain everything they had been fighting for, and much more besides, after Vatican II.

It was Pius XII’s profound ambivalence that made effective control of the Liturgical Movement impossible. Whose side was he really on? Opposing factions claimed victory.

But the claim for the traditionalist party rang hollow when they found themselves abandoned to the tender mercies of Bugnini who was given the executive role on the 1948 Commission for the General Reform of the Liturgy by none other than Pius XII himself.

Continued

- The British statesman, Sir Winston Churchill, once famously remarked with reference to Hitler that appeasement is tantamount to feeding a crocodile in the hope that it will eat you last;

- Mediator Dei § 4;

- Ibid., § 7;

- This included the unauthorized use of “Dialogue Masses,” the vernacular, Mass facing the people, Offertory processions, Communion in the hand and ecumenical services;

- The reference is to the massive 16th-century Italian sculpture known as the Colosso dell'Appennino or the Appennine Colossus created by the artist Giambologna. The giant statue sits brooding over a pool, staring into its murky depths like a malevolent spirit. Its body contains a number of interconnecting chambers while inside its head there is a sort of fireplace which, when lighted, emits billows of smoke from its nose. Beauduin fuming against Catholic Tradition?

- Ironically, this applies to Pius XII’s own reform of the Psalter which he mentioned in Mediator Dei § 6: “Only a short while previously, with the design of rendering the prayers of the liturgy more correctly understood and their truth and unction more easy to perceive, We arranged to have the Book of Psalms, which forms such an important part of these prayers in the Catholic Church, translated again into Latin from their original text.”

- Pope Paul VI, Apostolic Constitution Missale Romanum, April 3, 1969;

- In his Memoirs, Weakland explained how he was a protégé of Bugnini who assured him of Pope Paul’s high regard for him. See Rembert G. Weakland, A Pilgrim in a Pilgrim Church: Memoirs of a Catholic Archbishop, Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 2009, pp, 127-128;

- Beauduin outlined this stratagem in the Editorial of the first issue of La Maison-Dieu, January 1945, p. 21;

- A. Bugnini, The Reform of the Liturgy: 1948-1975, The Liturgical Press, 1990, p. 11.

Posted November 5, 2014

______________________

______________________

Volume I |

Volume II |

Volume III |

Volume IV |

Volume V |

Volume VI |

Volume VII |

Volume VIII |

Volume IX |

Volume X |

Volume XI |

Special Edition |