Traditionalist Issues

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Dialogue Mass - CXXXI

Pre- & Post-Vatican II Seminary

Training Compared

For 400 years after the Council of Trent’s reform of the seminaries, the life of a Major Seminarian was much the same the world over: a tightly structured order of the day, comprising early rising, Mass, Breviary, Rosary, visits to the Blessed Sacrament, prescribed studies (including Scholastic Metaphysics), meditation, spiritual reading, ascetical practices, a strict dress code, recreation and the Great Silence before retiring at the end of the day.

The strict regime resembled that of a tightly-knit monastic community (pre-conciliar, of course) insofar as it enforced separation from women, discouraged close friendships with other seminarians, restricted students to seminary grounds and forbade them, among other things, to frequent places of entertainment. Minor Orders and the Sub-Diaconate were mandatory before Ordination to the priesthood.

The strict regime resembled that of a tightly-knit monastic community (pre-conciliar, of course) insofar as it enforced separation from women, discouraged close friendships with other seminarians, restricted students to seminary grounds and forbade them, among other things, to frequent places of entertainment. Minor Orders and the Sub-Diaconate were mandatory before Ordination to the priesthood.

It is this fixed order of seminary life, upheld by the requirements of ecclesiastical law, that the progressivist reformers disparagingly labelled “rigidity.”

But they entirely missed the point. It is obvious from this checklist that the principles upon which life in the seminary were founded arose from a desire to lead a life that was more spiritual, prayerful and austere, and that the goal to be achieved was the salvation of souls.

The symbolism of the ‘hortus conclusus’ (enclosed garden)

The idea of a pre-Vatican II seminary – often located in a secluded area and surrounded with a wall – was separation from the world in order to remove students from temptation, in the interests of the higher calling of celibacy. When Vatican II encouraged unlimited openness to worldly values, and re-envisioned the role of the priest to suit, the model of a seminary as a “world apart” from ordinary life was held up to scorn by progressivists as foolish and unpractical.

Those who chose to immerse themselves in the worldly ways of living encouraged by Vatican II failed to appreciate how the rich religious symbolism of the “enclosed garden,” dating back to the Canticle of Canticles (4:12), was an eminently fitting model for a seminary. This is clear from the following analogies.

Those who chose to immerse themselves in the worldly ways of living encouraged by Vatican II failed to appreciate how the rich religious symbolism of the “enclosed garden,” dating back to the Canticle of Canticles (4:12), was an eminently fitting model for a seminary. This is clear from the following analogies.

First, the garden (contrasted with Eden) was interpreted by the Church Fathers as an allegory of the nuptial union between Christ (the Bridegroom) and the Church (the Bride). It follows that the young men who aspire to the priesthood so as to become, like Our Lord, wedded exclusively to the Church, must live in conditions that foster fidelity. The most suitable conditions were found in the pre-conciliar seminaries, where the students were separated from worldly relationships, especially with women, which might entice them away from contemplating a celibate life.

Second, the biblical image of the hortus conclusus was also applied to the perpetual virginity of Our Lady insofar as the garden of her womb, made accessible only to the Holy Spirit at the moment of the Incarnation, was closed to all others. This Marian doctrine, believed by the Church from the earliest times, was expressed poetically by Fr. Henry Hawkins S.J. in 1633:

Second, the biblical image of the hortus conclusus was also applied to the perpetual virginity of Our Lady insofar as the garden of her womb, made accessible only to the Holy Spirit at the moment of the Incarnation, was closed to all others. This Marian doctrine, believed by the Church from the earliest times, was expressed poetically by Fr. Henry Hawkins S.J. in 1633:

“The Virgin was a garden round beset

With Rose, and Lillie, and sweet Violet,

Where fragrant Sentss without distast [offence] of Sinne

Invited GOD the Sonne to enter in.” 1

Fr. Hawkins also mentioned that the Incarnation was brought about by the action of the “Holie Spirit” operating “like a subtile wind” – so subtle, in fact, that the birth of the Savior left Mary’s virginity intact.

For those who aimed to lead a celibate life in imitation of the purity of the Blessed Virgin, no better living arrangements for their training could be devised than the protective walls of a seminary. Because of the weakness of Fallen Nature, these walls were considered necessary in order to screen out as much as possible the noxious influences of the modern world. They are all the more necessary in the present day when society is awash with materialism, hedonism and eroticism.

And third, the cloistered garden, a hallowed space of prayer and tranquillity walled off from the outside world, was recognized as an image of the interior life.

No matter how sound these arguments were in support of the Church’s former decision to build seminaries in areas remote from worldly influences, and to keep clerical students segregated from lay people, they made no impact on progressivist reformers in charge of the post-conciliar seminaries. The reason for this rejection of traditional seminaries is not hard to find.

Vatican II distorted the ends of the priesthood and the Church by playing down their essentially supernatural nature while at the same time placing vastly more emphasis on secular activities and humanitarian goals to be pursued together with all the inhabitants of the world. This objective of the progressivists was remarked upon by one of the Council Fathers, Bishop Rudolph Graber of Regensburg who charged that they aimed to “deprive the Church of her supernatural character, to amalgamate her with the world... and thus to pave the way for a standardized world religion in a centralized world state.”2

Vatican II distorted the ends of the priesthood and the Church by playing down their essentially supernatural nature while at the same time placing vastly more emphasis on secular activities and humanitarian goals to be pursued together with all the inhabitants of the world. This objective of the progressivists was remarked upon by one of the Council Fathers, Bishop Rudolph Graber of Regensburg who charged that they aimed to “deprive the Church of her supernatural character, to amalgamate her with the world... and thus to pave the way for a standardized world religion in a centralized world state.”2

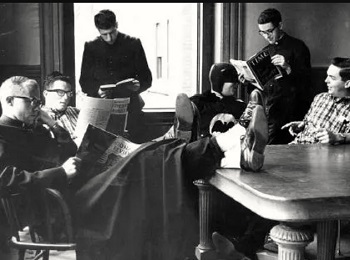

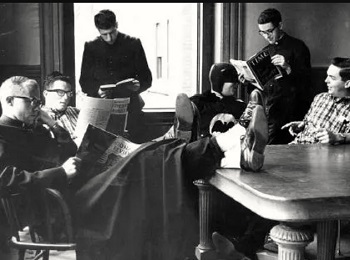

In this Masonic scheme of things, seminarians are presented with new objectives – the building up of the community in this world – for which he will need new skills – dialogue, listening, solidarity, conciliation, assembly-gathering etc. But these are suitable for the promotion of naturalistic ends, as we can see from the fact that they are required, for example, by any shop steward or union representative in the world of labor. Seminarians are expected to mix freely and socially with the laity and join in their efforts to “make a better world” for mankind.

And so the seminary which, as its name indicates, should be the seed bed of vocations in the supernatural sphere, becomes a construction site where trainee priests are given apprenticeships for naturalistic, Masonic projects. In this way, the purpose of the hortus conclusus becomes redundant.

Revolutionary Basic Plan for Priestly Formation

Now let us contrast the traditional manner of training priests with the methods based on the new concept of priesthood put forward by Vatican II. In March 1970, the Congregation for Catholic Education (which was then in charge of the seminaries) issued general guidelines for implementation by various Bishops’ Conferences around the world. The following points of the Basic Plan for Priestly Formation highlight what is required:

These new criteria for priestly training indicate that an anthropocentric revolution has taken place in response to Vatican II. This is the reverse of what pertained in the history of seminaries since they were first established by the Council of Trent.

These new criteria for priestly training indicate that an anthropocentric revolution has taken place in response to Vatican II. This is the reverse of what pertained in the history of seminaries since they were first established by the Council of Trent.

The whole tenor of the training programme betrays its subjectivist foundation, as priority over objective truth is given to the personal wishes of the subject, which fosters egoism and eventually a sort of self-deification. The Basic Plan for Priestly Formation exemplifies the new religion of “Personalism” put forward by Vatican II under the guise of “the dignity of man.”

All of this shows that the concept of the authority to govern exercised by a superior has been changed into a meeting of minds in a fraternal relationship among equals. The new kind of obedience is a misnomer, as it does not involve the submission of one’s will to that of another, but only a mutual agreement which is the result of dialogue.

It is evident that the Catholic idea of authority (to be obeyed because it comes from God) is here cast aside in favor of the autonomy of man who decides according to his own desires whether to obey or not. Thus, the goal of the priesthood has lost its transcendent orientation and is now primarily the service of man.

To put flesh on the bones of the Basic Plan for Priestly Formation, Fr. John J. Harrington C.M., an advisor to the American Bishops’ Conference, drew up a list of desiderata in 1973 which were subsequently adopted in US seminaries:

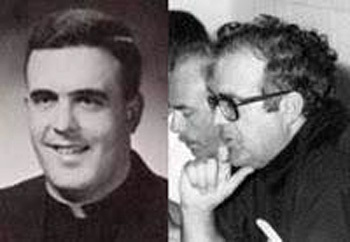

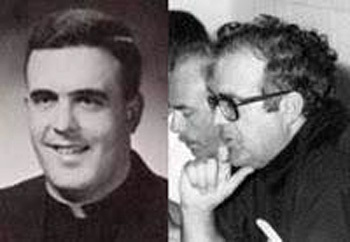

This is how an Irish-born priest, Fr. Hugh Behan – ordained in 1964 – voiced his criticism of the “old guard” of seminary Professors:

“[T]hey were prisoners of a system of negative theology and a culture that was destructive and produced the crisis that we face today. That is why suspicions of friendships even between the same sex in seminaries and convents and dangers of friendship with the laity were stressed, and hardly a word was said about the beauty and the power and the meaning of God’s love which is made present for us in the lives of other persons.”5

“[T]hey were prisoners of a system of negative theology and a culture that was destructive and produced the crisis that we face today. That is why suspicions of friendships even between the same sex in seminaries and convents and dangers of friendship with the laity were stressed, and hardly a word was said about the beauty and the power and the meaning of God’s love which is made present for us in the lives of other persons.”5

The case of Fr. Behan illustrates the consequences of the false optimism about human nature that was the keynote of Vatican II and the “New Evangelization.” The reformers set about destroying the very conditions considered in the Church’s age-old wisdom necessary for fostering holiness in seminarians – the strict discipline, the emphasis on penance and asceticism, the traditional, rule-bound liturgy of the seminaries.

All this was abandoned in the interests of greater freedom and self-determination, as seen in the above list. With the relaxation of morals encouraged by Vatican II, it is not surprising that the clergy abuse crisis exploded in the 1970s and the Church has been suffering the consequences ever since.

It is not without significance that after Fr. Behan criticized the pre-conciliar teaching for putting “a too heavy emphasis on guilt, particularly sexual sins,” 6 he himself was removed from the ministry by the Bishop of the Jefferson City Diocese in 1999 amid accusations of sexual misconduct stretching back for years.

Continued

Seminarians in the Newark Diocese 1900,

strict order & seriousness

It is this fixed order of seminary life, upheld by the requirements of ecclesiastical law, that the progressivist reformers disparagingly labelled “rigidity.”

But they entirely missed the point. It is obvious from this checklist that the principles upon which life in the seminary were founded arose from a desire to lead a life that was more spiritual, prayerful and austere, and that the goal to be achieved was the salvation of souls.

The symbolism of the ‘hortus conclusus’ (enclosed garden)

The idea of a pre-Vatican II seminary – often located in a secluded area and surrounded with a wall – was separation from the world in order to remove students from temptation, in the interests of the higher calling of celibacy. When Vatican II encouraged unlimited openness to worldly values, and re-envisioned the role of the priest to suit, the model of a seminary as a “world apart” from ordinary life was held up to scorn by progressivists as foolish and unpractical.

A closed world: St. Joseph’s Seminary

in Upholland, England

First, the garden (contrasted with Eden) was interpreted by the Church Fathers as an allegory of the nuptial union between Christ (the Bridegroom) and the Church (the Bride). It follows that the young men who aspire to the priesthood so as to become, like Our Lord, wedded exclusively to the Church, must live in conditions that foster fidelity. The most suitable conditions were found in the pre-conciliar seminaries, where the students were separated from worldly relationships, especially with women, which might entice them away from contemplating a celibate life.

Our Lady pictured in a closed garden, ny Jan van Eyck

“The Virgin was a garden round beset

With Rose, and Lillie, and sweet Violet,

Where fragrant Sentss without distast [offence] of Sinne

Invited GOD the Sonne to enter in.” 1

Fr. Hawkins also mentioned that the Incarnation was brought about by the action of the “Holie Spirit” operating “like a subtile wind” – so subtle, in fact, that the birth of the Savior left Mary’s virginity intact.

For those who aimed to lead a celibate life in imitation of the purity of the Blessed Virgin, no better living arrangements for their training could be devised than the protective walls of a seminary. Because of the weakness of Fallen Nature, these walls were considered necessary in order to screen out as much as possible the noxious influences of the modern world. They are all the more necessary in the present day when society is awash with materialism, hedonism and eroticism.

And third, the cloistered garden, a hallowed space of prayer and tranquillity walled off from the outside world, was recognized as an image of the interior life.

No matter how sound these arguments were in support of the Church’s former decision to build seminaries in areas remote from worldly influences, and to keep clerical students segregated from lay people, they made no impact on progressivist reformers in charge of the post-conciliar seminaries. The reason for this rejection of traditional seminaries is not hard to find.

After Vatican II a casual & worldly attitude

entered the seminarians

In this Masonic scheme of things, seminarians are presented with new objectives – the building up of the community in this world – for which he will need new skills – dialogue, listening, solidarity, conciliation, assembly-gathering etc. But these are suitable for the promotion of naturalistic ends, as we can see from the fact that they are required, for example, by any shop steward or union representative in the world of labor. Seminarians are expected to mix freely and socially with the laity and join in their efforts to “make a better world” for mankind.

And so the seminary which, as its name indicates, should be the seed bed of vocations in the supernatural sphere, becomes a construction site where trainee priests are given apprenticeships for naturalistic, Masonic projects. In this way, the purpose of the hortus conclusus becomes redundant.

Revolutionary Basic Plan for Priestly Formation

Now let us contrast the traditional manner of training priests with the methods based on the new concept of priesthood put forward by Vatican II. In March 1970, the Congregation for Catholic Education (which was then in charge of the seminaries) issued general guidelines for implementation by various Bishops’ Conferences around the world. The following points of the Basic Plan for Priestly Formation highlight what is required:

- “A greater esteem for the person” [i.e. individual wishes must be catered for];

- Removal of anything whose reason is an unjustified “convention” [i.e. no rights accorded to Tradition];

- Genuine dialogue must be established among all parties [i.e. no orders from “on high”];

- More numerous contacts with the world must be encouraged [i.e. secular life is not to be viewed as a danger to priestly vocations, and precautions can be abandoned];

- Everything that is prescribed or demanded should show the reason on which it is based, and be carried out in freedom [i.e. no one must be constrained to obey].3

The whole tenor of the training programme betrays its subjectivist foundation, as priority over objective truth is given to the personal wishes of the subject, which fosters egoism and eventually a sort of self-deification. The Basic Plan for Priestly Formation exemplifies the new religion of “Personalism” put forward by Vatican II under the guise of “the dignity of man.”

All of this shows that the concept of the authority to govern exercised by a superior has been changed into a meeting of minds in a fraternal relationship among equals. The new kind of obedience is a misnomer, as it does not involve the submission of one’s will to that of another, but only a mutual agreement which is the result of dialogue.

It is evident that the Catholic idea of authority (to be obeyed because it comes from God) is here cast aside in favor of the autonomy of man who decides according to his own desires whether to obey or not. Thus, the goal of the priesthood has lost its transcendent orientation and is now primarily the service of man.

To put flesh on the bones of the Basic Plan for Priestly Formation, Fr. John J. Harrington C.M., an advisor to the American Bishops’ Conference, drew up a list of desiderata in 1973 which were subsequently adopted in US seminaries:

- “Frequent “one-on-one” encounters of long duration with other seminarians in which both parties manifest themselves rather totally and tell each other of their mutual regard;

- Frequent informal gatherings of seminarians that can consume much time in a working day;

- Liturgical celebrations in which the emphasis is often on the communal shedding of inhibition, a short-cut to “feeling at one with the Lord and one another”;

- Apostolates to adolescents in which acceptance is both easily obtained and given;

- Avoidance of dress or behavior that will mark him [the seminarian] off as “different” from his contemporaries and thus possibly make acceptance by others more difficult;

- Courses and classes that will be of immediate assistance in his problem of “belonging.”4

Seminarians at Holy Trinity Seminary in Irving TX, immersed in the modern world

This is how an Irish-born priest, Fr. Hugh Behan – ordained in 1964 – voiced his criticism of the “old guard” of seminary Professors:

Fr. Hugh Behan in 1960; today, at right,

he is accused of molesting minors

The case of Fr. Behan illustrates the consequences of the false optimism about human nature that was the keynote of Vatican II and the “New Evangelization.” The reformers set about destroying the very conditions considered in the Church’s age-old wisdom necessary for fostering holiness in seminarians – the strict discipline, the emphasis on penance and asceticism, the traditional, rule-bound liturgy of the seminaries.

All this was abandoned in the interests of greater freedom and self-determination, as seen in the above list. With the relaxation of morals encouraged by Vatican II, it is not surprising that the clergy abuse crisis exploded in the 1970s and the Church has been suffering the consequences ever since.

It is not without significance that after Fr. Behan criticized the pre-conciliar teaching for putting “a too heavy emphasis on guilt, particularly sexual sins,” 6 he himself was removed from the ministry by the Bishop of the Jefferson City Diocese in 1999 amid accusations of sexual misconduct stretching back for years.

Continued

- Henry Hawkins SJ, Partheneia sacra, or, The mysterious and delicious garden of the sacred Parthenes: symbolically set forth and enriched with pious devises and emblemes for the entertainment of devout soules, contrived all to the honour of the incomparable Virgin Marie, Mother of God, for the pleasure and devotion especially of the Parthenian Sodalitie of her Immaculate Conception, Rouen: John Cousturier, 1633, p. 13.

- Rudolph Graber, Athanasius and the Church of Our Times, London: Van Duren, 1974, p. 37.

- The Congregation for Catholic Education, The Basic Plan for Priestly Formation, Introduction § 2, National Conference of Bishops, Washington, 1970.

- John J. Harrington CM, ‘Ten Years of Seminary Renewal’, American Ecclesiastical Review, November 1973, Vol. 167, Issue 9, p. 589

- Fr Hugh Behan, ‘Whatever became of Adolphe Tanquerey?’, The Furrow, Vol. 28, No. 3, March 1977, p. 169

- Fr Hugh Behan, Editor of the Catholic Missourian, the newspaper of the diocese of Jefferson City, ‘The Faithful Departing’, The Furrow, Vol. 49, No. 4, April 1998, p. 244

Posted October 27, 2023

______________________

______________________

Volume I |

Volume II |

Volume III |

Volume IV |

Volume V |

Volume VI |

Volume VII |

Volume VIII |

Volume IX |

Volume X |

Volume XI |

Special Edition |