Traditionalist Issues

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Dialogue Mass - CIV

Minor Orders Placed at the

Mercy of the Zeitgeist

It is certain that the Minor Orders did not stand a chance of survival after Vatican II’s call for aggiornamento. Mgr. Bugnini, as Secretary of the Consilium, recorded in 1966 that its members unanimously approved the following proposal regarding the Minor Orders:

“The Church may abolish, change or increase the number of the orders below the diaconate, as any given period needs or finds useful.” (1)

This shows that the dominant strain of thought among the reformers was that the Minor Orders were obsolete and were to be scrapped, like yesterday’s technology, for innovative models more in keeping with modern expectations. It is also evidence of the reformers’ desire to fashion and refashion the liturgy at will, subject only to the criterion of what “any given period needs or finds useful.”

In other words, the Minor Orders were given short shrift because a committee had sat and decided that they served no useful purpose: safeguarding the integrity of the priesthood was evidently not considered a worthy motive for their retention.

In other words, the Minor Orders were given short shrift because a committee had sat and decided that they served no useful purpose: safeguarding the integrity of the priesthood was evidently not considered a worthy motive for their retention.

Here we touch on the hidden springs of the revolution: The plan to ravage the Minor Orders was hatched in the committee room under Bugnini’s close supervision, and the target of the members of Paul VI’s Consilium was revealed by Bugnini to be that of an ever-evolving reform. We can further extrapolate that the same principles were applied to the creation of the Novus Ordo liturgy in 1969.

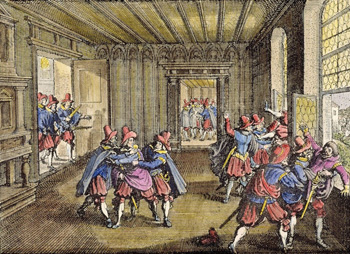

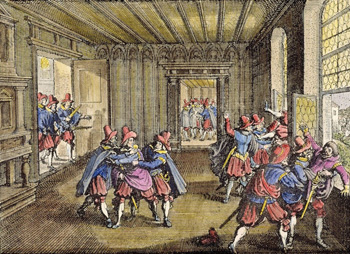

Out of the window: ‘defenestration’ of the Minor Orders

Now we will turn to the manner in which the Minor Orders were forcibly and peremptorily removed – “defenestrated” (literally thrown out of the window) would seem the most appropriate term to use in the circumstances. Historically a swift and effective means of dispatching one’s opponents, (2) the act of defenestration also facilitated the ejection of a substantial portion of the Church’s liturgical traditions from the time of Pope Pius XII onwards.

What follows is a summary of Mgr. Bugnini’s account of the behind-the-scenes operations of progressivists and their representatives on the Consilium to rid the Church of Minor Orders.

What follows is a summary of Mgr. Bugnini’s account of the behind-the-scenes operations of progressivists and their representatives on the Consilium to rid the Church of Minor Orders.

Of particular note is his casual reference to a groundswell of quiet rebellion against Minor Orders among seminarians in the German-speaking countries. It will become apparent that we are dealing with an act of ecclesiastical dissent that not only went uncorrected by the local Ordinaries, but was actually endorsed by Paul VI several years before he issued Ministeria quaedam. The whole account remains an unrivalled guide to what went on in the corridors of the Vatican to bring about the desired objective.

First, Mgr. Bugnini tells us about a group of married seminarians in Rottenburg who demanded to proceed straight to the diaconate without having to submit to Minor Orders. In October 1968, their Bishop requested a dispensation from the Pope, which Paul VI granted through the Congregation for the Sacraments “as a favor, on this one occasion.” (3)

Follow me & keep the paycheques coming

What Bugnini did not mention was that the Congregation was already parti pris in the situation.

What Bugnini did not mention was that the Congregation was already parti pris in the situation.

According to Dom Bernard Botte, its President, Card. Samoré, having consulted his expert opinion, concluded that the Minor Orders should be abolished because they were “no longer of any relevance in the Church” – and paid Dom Bernard 10,000 lira for his advice. (4)

But, unsurprisingly, the Rottenburg case did not remain for long a one-off event for, continues Bugnini, “requests multiplied: France, Belgium, Germany, Austria, Switzerland and Canada asked permission to do away with first tonsure and Minor Orders” for “candidates for the priesthood.” (5)

The water is now on this side of the dike

The only person standing between salvation and disaster for the Minor Orders was Paul VI, but once he produced a chink in the restraining wall of the dike, an unstoppable flood of water cascaded through the weakened area. Not even the Little Dutch Boy could have saved the situation.

If revolution finds opportunities in chaos, the reformers were well on their way to victory, considering the effects of Paul VI’s policy of non-intervention while national Episcopal Conferences took matters into their own hands: according to Bugnini, they simply “acted on their own responsibility and undertook their own reform.” (6)

Mgr. Bugnini describes, without making the least criticism, a mutiny staged by seminarians in the Diocese of Linz, Austria, against the discipline of Minor Orders. Their Bishop, Franz Zauner – a member of the Consilium with a marked propensity for defenestration of all things traditional (7) – naturally supported their cause. In a 1970 letter, he threw the gauntlet down at the Pope’s feet with the statement that “in his diocese the candidates for tonsure and the Minor Orders are this year refusing to receive them in the traditional form, claiming that they are ‘absurd and not fulfillable’ (sinnwidrig und nicht vollziehbar).” The Bishop added that they had “even supplied a new form [of ordination] that they want the consecrating bishop to use.” (8)

Mgr. Bugnini describes, without making the least criticism, a mutiny staged by seminarians in the Diocese of Linz, Austria, against the discipline of Minor Orders. Their Bishop, Franz Zauner – a member of the Consilium with a marked propensity for defenestration of all things traditional (7) – naturally supported their cause. In a 1970 letter, he threw the gauntlet down at the Pope’s feet with the statement that “in his diocese the candidates for tonsure and the Minor Orders are this year refusing to receive them in the traditional form, claiming that they are ‘absurd and not fulfillable’ (sinnwidrig und nicht vollziehbar).” The Bishop added that they had “even supplied a new form [of ordination] that they want the consecrating bishop to use.” (8)

The revolt against constituted authority represents a state of depravity that puts the German revolutionaries in the company of the Church’s opponents such as the 16th-century Protestant and 18th-century Jansenist heretics who likewise rejected Minor Orders. We can see in this expression of wayward passions a grave challenge to the preservation of Tradition that would have the most profound implications for the unity of the Church.

It was an early manifestation of the de facto schism operating today among the German Hierarchy of the “Synodal Church.” Allowing rebellious groups to dictate Church policy lies at the root of all Vatican II-inspired reforms, and the abolition of Minor Orders was no exception.

Bugnini’s joke: ‘While Rome is consulted, Saguntum falls’

Bugnini notes that Paul VI’s reaction was to remain aloof while dissent in the German-speaking lands ran rife.

Although the matter had gone beyond a joke, Bugnini was evidently much amused at the situation which he compared to the siege of Saguntum by his namesake, Hannibal, in 219 B.C. Those who are familiar with the history of the event will get the joke.

When Rome’s Iberian ally, Saguntum, was threatened by the Carthaginian General, Hannibal, its citizens appealed to Rome for help. But all that Rome sent were envoys to make diplomatic overtures to the Carthaginians and to convey its highest esteem for the people of Saguntum. It was not willing, however, to commit any force behind its words to save its stricken friends.

When Rome’s Iberian ally, Saguntum, was threatened by the Carthaginian General, Hannibal, its citizens appealed to Rome for help. But all that Rome sent were envoys to make diplomatic overtures to the Carthaginians and to convey its highest esteem for the people of Saguntum. It was not willing, however, to commit any force behind its words to save its stricken friends.

Pope Paul VI’s attitude towards Tradition was similarly ambivalent. He sent his nuncio to negotiate with the Germans, praised the Minor Orders for their venerable antiquity, and temporized for years, calling for a committee to be formed, discussions to be held by the Congregation for the Sacraments in collaboration with the Consilium, a study to be made and guidelines to be drawn up. (9)

Only when the rebellion was completely out of hand, having spread to dissident Episcopal Conferences around the world, did he finally intervene in 1972. But by then Saguntum, as it were, had been taken hostage by the enemy.

In Ministeria quaedam, he gave the Minor Orders his thumbs-down with all the finality of a Roman Emperor in the arena whose imperium required the most severe damage to be inflicted on the Christian priesthood.

Continued

“The Church may abolish, change or increase the number of the orders below the diaconate, as any given period needs or finds useful.” (1)

This shows that the dominant strain of thought among the reformers was that the Minor Orders were obsolete and were to be scrapped, like yesterday’s technology, for innovative models more in keeping with modern expectations. It is also evidence of the reformers’ desire to fashion and refashion the liturgy at will, subject only to the criterion of what “any given period needs or finds useful.”

Paul VI with members of Consilium

Here we touch on the hidden springs of the revolution: The plan to ravage the Minor Orders was hatched in the committee room under Bugnini’s close supervision, and the target of the members of Paul VI’s Consilium was revealed by Bugnini to be that of an ever-evolving reform. We can further extrapolate that the same principles were applied to the creation of the Novus Ordo liturgy in 1969.

Out of the window: ‘defenestration’ of the Minor Orders

Now we will turn to the manner in which the Minor Orders were forcibly and peremptorily removed – “defenestrated” (literally thrown out of the window) would seem the most appropriate term to use in the circumstances. Historically a swift and effective means of dispatching one’s opponents, (2) the act of defenestration also facilitated the ejection of a substantial portion of the Church’s liturgical traditions from the time of Pope Pius XII onwards.

The defenestration of Prague - 1618 - Protestants threw Catholic imperial officials out of the window

Of particular note is his casual reference to a groundswell of quiet rebellion against Minor Orders among seminarians in the German-speaking countries. It will become apparent that we are dealing with an act of ecclesiastical dissent that not only went uncorrected by the local Ordinaries, but was actually endorsed by Paul VI several years before he issued Ministeria quaedam. The whole account remains an unrivalled guide to what went on in the corridors of the Vatican to bring about the desired objective.

First, Mgr. Bugnini tells us about a group of married seminarians in Rottenburg who demanded to proceed straight to the diaconate without having to submit to Minor Orders. In October 1968, their Bishop requested a dispensation from the Pope, which Paul VI granted through the Congregation for the Sacraments “as a favor, on this one occasion.” (3)

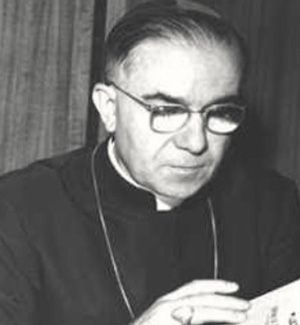

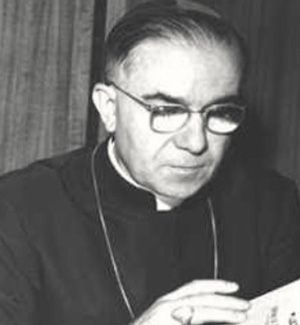

Follow me & keep the paycheques coming

Card. Antonio Samoré

According to Dom Bernard Botte, its President, Card. Samoré, having consulted his expert opinion, concluded that the Minor Orders should be abolished because they were “no longer of any relevance in the Church” – and paid Dom Bernard 10,000 lira for his advice. (4)

But, unsurprisingly, the Rottenburg case did not remain for long a one-off event for, continues Bugnini, “requests multiplied: France, Belgium, Germany, Austria, Switzerland and Canada asked permission to do away with first tonsure and Minor Orders” for “candidates for the priesthood.” (5)

The water is now on this side of the dike

The only person standing between salvation and disaster for the Minor Orders was Paul VI, but once he produced a chink in the restraining wall of the dike, an unstoppable flood of water cascaded through the weakened area. Not even the Little Dutch Boy could have saved the situation.

If revolution finds opportunities in chaos, the reformers were well on their way to victory, considering the effects of Paul VI’s policy of non-intervention while national Episcopal Conferences took matters into their own hands: according to Bugnini, they simply “acted on their own responsibility and undertook their own reform.” (6)

Paul VI warmly greets Arch. Bugnini

The revolt against constituted authority represents a state of depravity that puts the German revolutionaries in the company of the Church’s opponents such as the 16th-century Protestant and 18th-century Jansenist heretics who likewise rejected Minor Orders. We can see in this expression of wayward passions a grave challenge to the preservation of Tradition that would have the most profound implications for the unity of the Church.

It was an early manifestation of the de facto schism operating today among the German Hierarchy of the “Synodal Church.” Allowing rebellious groups to dictate Church policy lies at the root of all Vatican II-inspired reforms, and the abolition of Minor Orders was no exception.

Bugnini’s joke: ‘While Rome is consulted, Saguntum falls’

Bugnini notes that Paul VI’s reaction was to remain aloof while dissent in the German-speaking lands ran rife.

Although the matter had gone beyond a joke, Bugnini was evidently much amused at the situation which he compared to the siege of Saguntum by his namesake, Hannibal, in 219 B.C. Those who are familiar with the history of the event will get the joke.

A thumbs down to Minor Orders

Pope Paul VI’s attitude towards Tradition was similarly ambivalent. He sent his nuncio to negotiate with the Germans, praised the Minor Orders for their venerable antiquity, and temporized for years, calling for a committee to be formed, discussions to be held by the Congregation for the Sacraments in collaboration with the Consilium, a study to be made and guidelines to be drawn up. (9)

Only when the rebellion was completely out of hand, having spread to dissident Episcopal Conferences around the world, did he finally intervene in 1972. But by then Saguntum, as it were, had been taken hostage by the enemy.

In Ministeria quaedam, he gave the Minor Orders his thumbs-down with all the finality of a Roman Emperor in the arena whose imperium required the most severe damage to be inflicted on the Christian priesthood.

Continued

- Annibale Bugnini, The Reform of the Liturgy 1948-1975, p. 733.

- From the Latin de (down from) and fenestra (window), this word signifies the act of throwing someone or something out of a window. It was coined with reference to the second Defenestration of Prague (1618) when a group of Protestant Bohemian reformers threw two Catholic imperial officials and their secretary out of a window in Prague Castle, thus helping to precipitate the Thirty Years’ War, The word has an obvious analogy to the ejection of the Minor Orders at the instigation of a group of seminarians in Germany and Austria.

- A. Bugnini, The Reform of the Liturgy, p. 739.

- Bernard Botte, Le Mouvement Liturgique: témoignage et souvenirs, Desclée: Paris, 1973. On p. 175, Dom Bernard states that he received a letter from Cardinal Samoré, Prefect of the Congregation for the Sacraments to this effect: “Dans sa lettre, le cardinal Samoré me faisait savoir que la Congrégation des Sacrements ne voyait aucun inconvénient à l'abrogation des ordres mineurs, qui ne représentaient plus aucun intérêt pour la vie de l'Église”. (In his letter, Cardinal Samoré informed me that the Congregation for the Sacraments saw no problem in the abrogation of the Minor Orders which were no longer of any relevance in the life of the Church”.)

- A. Bugnini, The Reform of the Liturgy, p. 740.

- Ibid..

- Bishop Zauner’s comments on the reform of the liturgy were recorded by Fr. Henri De Lubac, Vatican Council Notebooks, trans. Andrew Stefanelli and Anne Englund Nash, San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 2015. At Vatican II he loudly advocated “casting off” most of the traditional prayers and ceremonies of the Mass which he described as so many “impedimenta” (hindrances, useless baggage) on the path to reform. His disrespect for the sacred is evident from this quote: “Some have invoked a text from Exodus [3:5} not to change anything; my conclusion is the exact opposite: depone tua calceamenta, id est, rejice impedimenta [remove your sandals, that is, cast off all obstacles]”. Ibid., vol. 1, p. 242.

- A. Bugnini, The Reform of the Liturgy, p. 741.

- Details are provided by Bugnini, ibid., pp. 738-751.

Posted May 31, 2021

______________________

______________________

Volume I |

Volume II |

Volume III |

Volume IV |

Volume V |

Volume VI |

Volume VII |

Volume VIII |

Volume IX |

Volume X |

Volume XI |

Special Edition |