Traditionalist Issues

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Dialogue Mass - CXXXIII

Examples of Vatican II’s Failed Seminary Experimentation

If American seminaries, as Fr. Poole observed, have undergone a revolution in the wake of Vatican II, the same can be said of other such institutions around the world. We will now look at three British seminaries that had been established within 150 years before Vatican II, focusing on their commitment to promoting the Catholic Faith, and comparing them with the innovative seminary training recommended by the Council and put into effect by diocesan bishops.

Seminary of Ushaw College

St. Cuthbert’s College Ushaw, near Durham, was the principal Roman Catholic seminary in the North of England. Having started its working life as the English College in Douai, France, in 1568 with the help of refugees from the persecution of Catholics in England by Queen Elizabeth I, it was hit by a second wave of persecution during the French Revolution. It was relocated to England where the Douai priests founded Ushaw College in 1808. It finally closed its doors in 2011 on account of a shortage of vocations.

After its glorious 400-year history which witnessed hundreds of ordinations and the death of 158 priest martyrs (who had secretly slipped back to England in Elizabethan times to minister to the beleaguered Catholic population), Ushaw met an inglorious end – at the hands of today’s Bishops. Its passing is generally regarded with indifference by most people, and even welcomed by some as the end of a bygone era of vigorous defense of the Catholic Faith.

After its glorious 400-year history which witnessed hundreds of ordinations and the death of 158 priest martyrs (who had secretly slipped back to England in Elizabethan times to minister to the beleaguered Catholic population), Ushaw met an inglorious end – at the hands of today’s Bishops. Its passing is generally regarded with indifference by most people, and even welcomed by some as the end of a bygone era of vigorous defense of the Catholic Faith.

The seminary, a magnificent building in extensive grounds, with a main altar that is a Puginesque masterpiece, is now a tourist attraction, hosting a medley of secular activities – start-up businesses, art exhibitions, music and theatre events, marriages and civil partnerships, wedding receptions, drinks parties and food festivals. A seminary trying to finance itself without students is as preposterous as a hospital trying to do the same without patients.

On May 8, 1987, the Catholic paper, The Universe, published a full-page story on Ushaw and on its reformed programme of formation, which gives us an idea of the kind of identity its future priests were expected to have. One student said: “The priest’s role is now seen as that of co-ordinator of the parish gifts.” Another summed up his idea of the priesthood vacuously as “to love and be loved as part of a loving community.” However, in the full-page article on training priests, the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass was never alluded to – not once.

Upholland Seminary

St. Joseph’s College, Upholland, in the Archdiocese of Liverpool, was founded by Arch. Bernard O’Reilly in 1880 to be the seminary serving the North West of England. In the ensuing decades, the number of seminarians (both minor and major) grew so rapidly that an extension was built by Arch. Frederick Keating, completed posthumously in 1930. As with Ushaw, the scale and magnificence of the buildings and grounds were breathtaking, reflecting the importance that the Church attached to the purpose of the Seminary’s existence. A contemporary commentator remarked:

“Now we are privileged to look upon the whole majestic pile to see the full mid-day glory of the ‘garden enclosed.’”1

Dr. Peter Doyle, a former student and member of staff at St. Joseph’s College, provided documentary evidence of Arch. Keating’s vision for the training of priests. The Archbishop said it was to be “a centre of sacred learning, an exemplar of religious observance, a treasure-house of ecclesiastical culture.” The teaching staff would be well qualified and “unsullied by Liberalism.” The Rector from 1926 to 1942, Msgr. Joseph Dean, chosen by the Archbishop, was a Scripture scholar who enforced unbending discipline and traditional practice on all seminarians. The Archbishop maintained that the views expressed by the Professors should always be strictly in line with those of Rome as conveyed through the Catholic Hierarchy.2

Dr. Peter Doyle, a former student and member of staff at St. Joseph’s College, provided documentary evidence of Arch. Keating’s vision for the training of priests. The Archbishop said it was to be “a centre of sacred learning, an exemplar of religious observance, a treasure-house of ecclesiastical culture.” The teaching staff would be well qualified and “unsullied by Liberalism.” The Rector from 1926 to 1942, Msgr. Joseph Dean, chosen by the Archbishop, was a Scripture scholar who enforced unbending discipline and traditional practice on all seminarians. The Archbishop maintained that the views expressed by the Professors should always be strictly in line with those of Rome as conveyed through the Catholic Hierarchy.2

Keating’s successor as Archbishop of Liverpool, Msgr. Richard Downey, who was first a Professor of Dogmatic Theology at Upholland and then its Vice-Rector, defended the seminary system as the traditionally-conceived hortus conclusus designed for spiritual growth:

“The candidate is not encouraged to be clever or smart, to uphold strange and original views, to be abreast of the fleeting novelties of the day, to break away from the abiding, age-long traditions of the Church. For this the Church wisely ordains that at an early age he be withdrawn from the world and its dangers to within the sheltering walls of the seminary, for this the intensive culture of charity, chastity, humility and obedience; for this the many spiritual exercises, the constant round of prayers, mental and vocal, the daily Mass and Communion, the visits to the Blessed Sacrament and the shrine of Mary, frequent confession that the soul lose not its lustre, spiritual direction, weekly conference, monthly recollection, annual retreat, constant encouragement, exhortation, admonition, correction.”3

This is important to keep in mind when we come to examine the changes in seminary formation introduced by the Vatican II reforms and their impact on the future of St. Joseph’s College.

When the last senior seminarians left Upholland in 1975 to join the few remaining ones at Ushaw, their quarters were turned into the Upholland Northern Institute (UNI), a centre for lay leadership and the re-education of clergy, with Fr. Kevin Kelly as its founding Director. Fr. Kelly explained:

“As a result of the Second Vatican Council, adult Christian education for laity and in-service training for clergy and religious became key priorities.”4

Its purpose was not to train men for the priesthood, but “to promote Vatican II renewal.”

In his role as Director of the UNI, Fr. Kelly initiated pioneering educational and formational programmes, as outlined in his book 50 Years Receiving Vatican II – a Personal Odyssey.5

He also invited in visiting lecturers with highly unorthodox views on moral issues, such as Fr. Bernard Häring and Fr. Charles Curran. Like them, he stressed the importance of human experience and the changed approach to the theology of marriage found in Vatican II. He was succeeded in 1980 by Fr. Vincent Nichols, now Cardinal Archbishop of Westminster.

The coup de grace came when Arch. Patrick Kelly of Liverpool decided to close St. Joseph’s in 1996. The building, together with its grounds (where the mortal remains of Bishop O’Reilly and Bishop Keating, the two Prelates to whom St. Joseph’s Seminary owed its existence and development, had been buried), were sold to a development company in 2003.

St. Peter’s Seminary

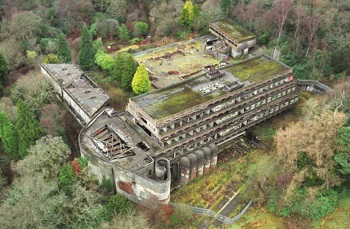

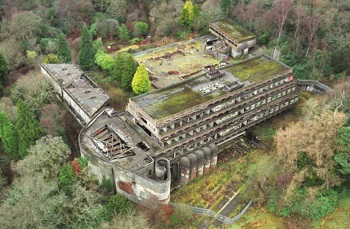

Surrounded by acres of Scottish woodland, St. Peter’s Seminary, Cardross, is an example of Le Corbusier’s modernist, brutalist architecture. Built entirely in concrete – including its altars – it has the appearance of a multi-tiered car park or a post-WWII Soviet tenement building that fits with the communist ideology. The dystopian seminary was opened in 1966, buoyed up by the wave of optimism launched by Vatican II’s promise of a “New Springtime” for the Church. It closed 14 years later for lack of sufficient vocations, without ever having reached anything like it its intended capacity of 100 seminarians.

By the time it opened, however, its demise was already pre-empted by Vatican II’s decision to downplay the importance of the ordained priesthood and exalt the role of the laity as the key to the Church’s future. Its gaunt and hulking skeleton is all that remains after decades of dereliction. The Archdiocese of Glasgow once described it as an “albatross around its neck.” They could not sell it or even give it away for free; nor could they demolish it, as it was an A-listed building. So they were stuck with the eyesore, until it was transferred to a charitable trust in 2020. So much for the ruin of material property, not to mention the waste of diocesan money and the ruin of priceless souls that accompanied it.

By the time it opened, however, its demise was already pre-empted by Vatican II’s decision to downplay the importance of the ordained priesthood and exalt the role of the laity as the key to the Church’s future. Its gaunt and hulking skeleton is all that remains after decades of dereliction. The Archdiocese of Glasgow once described it as an “albatross around its neck.” They could not sell it or even give it away for free; nor could they demolish it, as it was an A-listed building. So they were stuck with the eyesore, until it was transferred to a charitable trust in 2020. So much for the ruin of material property, not to mention the waste of diocesan money and the ruin of priceless souls that accompanied it.

As a final irony, the modernist structure that was built to house a typically Vatican II-era generation of men and imbue them with a “naturalist,” this-worldly view of the priesthood, was itself overtaken by the forces of Nature: it was slowly but surely encroached by the surrounding woodland, eroded by the elements and subjected to the repeated depredations of vandals. The site, which has been long exposed to the scorn and derision of sightseers, reinforces the humiliation of the Catholic priesthood initiated at Vatican II. The last word can go to a writer who visited the devastated vineyard:

“As one descends a stone staircase littered with broken glass, there are yet visible many such altars, all in rows, altars that have long since fallen into disrepair. Today these altars are marked and defaced by obscene and macabre graffiti. The overall scene is a pitiful one; it is more Tarkovsky [a Russian film producer] than St. Thomas Aquinas.”6

Where the real fault in seminary closures lies

When the original founder of Upholland, Bishop O’Reilly, died, the 19th-century Liverpool priest, Fr. James Nugent, wrote that the seminary project had been “the cherished child of his heart, even to his last breath.”7

In a cruel and perverse fate, that child is no longer cherished by the clergy, because it was unloved, unsung and neglected by them when they collectively transferred their allegiance from Tradition to the revolutionary principles of Vatican II.

Vatican II’s contribution to the crisis in priestly identity

Just as it did with Matrimony, the Council inverted the ends of the priesthood; it accomplished this by placing far greater emphasis on the role of the priest as a service to man than to God. This broader vision left the way open to interpretations which included anything from gun-running in Latin America by priests and nuns, to clerical support for adultery and same-sex unions. The Council’s innovative doctrines encouraged the clergy and laity to adopt the cult of man over and above the cult of God, to prefer earthly considerations to heavenly realities, the profane to the sacred, the secular to the religious, and to exalt the laity over the clergy. As the Council sought a compromise between unchangeable doctrine and the anti-Christian theories of the modern world, the immutable principles of the Moral Law were subordinated to the free expression of modern man’s impulses and desires.

What is the priest? After Vatican II, the question is still up in the air

The Coadjutor Archbishop Thomas Murphy of Seattle asked this very question in 1988, but was still searching for an answer over 20 years after the Council’s Decree on the Ministry and life of Priests:

“The question – What is the priest? – is of tremendous significance today because when we are able to articulate a theology of the priesthood that is appropriated by the Christian community, then we will have a clearer idea of the direction of seminary education and formation today, in its task of preparing ordained leaders for the Church of tomorrow.”8

This is an admission that in the post-Vatican II Church even Bishops are still unsure of the answer. A radical shift from the transcendent to the mundane had taken place in the modern Church’s understanding of the sacramental priesthood, which was bound to impact on the kind of seminary training received by those seeking Ordination. The basic problem was that the meaning of the sacramental priesthood had been compromised by the Council’s technique of obfuscation (literally throwing into the shadow) of the priestly office of sacrifice, leading to confusion about the identity of the priest.

So it would not be an exaggeration to say that many of today’s priests do not seem to know what they are. That is because the Council sidelined the traditional teaching that their first and highest duty, the raison d’être of their ministry, is to go up to the altar of God to offer the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass for the living and the dead. This supernatural mission is encapsulated in the immortal phrase, Introibo ad altare Dei, the opening words of the traditional Mass that the reformers have been making every effort to extinguish.

So it would not be an exaggeration to say that many of today’s priests do not seem to know what they are. That is because the Council sidelined the traditional teaching that their first and highest duty, the raison d’être of their ministry, is to go up to the altar of God to offer the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass for the living and the dead. This supernatural mission is encapsulated in the immortal phrase, Introibo ad altare Dei, the opening words of the traditional Mass that the reformers have been making every effort to extinguish.

It cannot be denied that the differences between the two systems of seminary formation – pre- and post-Vatican II – outlined in this article could not be starker; nor could those between how priests perceived themselves and their mission before and after Vatican II be more evident. The Council, then, can be seen as a point of inflection in the history of the post-Conciliar Church that would determine the course of future developments in the area of priestly vocations.

Continued

Seminary of Ushaw College

St. Cuthbert’s College Ushaw, near Durham, was the principal Roman Catholic seminary in the North of England. Having started its working life as the English College in Douai, France, in 1568 with the help of refugees from the persecution of Catholics in England by Queen Elizabeth I, it was hit by a second wave of persecution during the French Revolution. It was relocated to England where the Douai priests founded Ushaw College in 1808. It finally closed its doors in 2011 on account of a shortage of vocations.

Ushaw College

The seminary, a magnificent building in extensive grounds, with a main altar that is a Puginesque masterpiece, is now a tourist attraction, hosting a medley of secular activities – start-up businesses, art exhibitions, music and theatre events, marriages and civil partnerships, wedding receptions, drinks parties and food festivals. A seminary trying to finance itself without students is as preposterous as a hospital trying to do the same without patients.

On May 8, 1987, the Catholic paper, The Universe, published a full-page story on Ushaw and on its reformed programme of formation, which gives us an idea of the kind of identity its future priests were expected to have. One student said: “The priest’s role is now seen as that of co-ordinator of the parish gifts.” Another summed up his idea of the priesthood vacuously as “to love and be loved as part of a loving community.” However, in the full-page article on training priests, the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass was never alluded to – not once.

Upholland Seminary

St. Joseph’s College, Upholland, in the Archdiocese of Liverpool, was founded by Arch. Bernard O’Reilly in 1880 to be the seminary serving the North West of England. In the ensuing decades, the number of seminarians (both minor and major) grew so rapidly that an extension was built by Arch. Frederick Keating, completed posthumously in 1930. As with Ushaw, the scale and magnificence of the buildings and grounds were breathtaking, reflecting the importance that the Church attached to the purpose of the Seminary’s existence. A contemporary commentator remarked:

“Now we are privileged to look upon the whole majestic pile to see the full mid-day glory of the ‘garden enclosed.’”1

Upholland Seminary

Keating’s successor as Archbishop of Liverpool, Msgr. Richard Downey, who was first a Professor of Dogmatic Theology at Upholland and then its Vice-Rector, defended the seminary system as the traditionally-conceived hortus conclusus designed for spiritual growth:

“The candidate is not encouraged to be clever or smart, to uphold strange and original views, to be abreast of the fleeting novelties of the day, to break away from the abiding, age-long traditions of the Church. For this the Church wisely ordains that at an early age he be withdrawn from the world and its dangers to within the sheltering walls of the seminary, for this the intensive culture of charity, chastity, humility and obedience; for this the many spiritual exercises, the constant round of prayers, mental and vocal, the daily Mass and Communion, the visits to the Blessed Sacrament and the shrine of Mary, frequent confession that the soul lose not its lustre, spiritual direction, weekly conference, monthly recollection, annual retreat, constant encouragement, exhortation, admonition, correction.”3

This is important to keep in mind when we come to examine the changes in seminary formation introduced by the Vatican II reforms and their impact on the future of St. Joseph’s College.

When the last senior seminarians left Upholland in 1975 to join the few remaining ones at Ushaw, their quarters were turned into the Upholland Northern Institute (UNI), a centre for lay leadership and the re-education of clergy, with Fr. Kevin Kelly as its founding Director. Fr. Kelly explained:

“As a result of the Second Vatican Council, adult Christian education for laity and in-service training for clergy and religious became key priorities.”4

Its purpose was not to train men for the priesthood, but “to promote Vatican II renewal.”

In his role as Director of the UNI, Fr. Kelly initiated pioneering educational and formational programmes, as outlined in his book 50 Years Receiving Vatican II – a Personal Odyssey.5

He also invited in visiting lecturers with highly unorthodox views on moral issues, such as Fr. Bernard Häring and Fr. Charles Curran. Like them, he stressed the importance of human experience and the changed approach to the theology of marriage found in Vatican II. He was succeeded in 1980 by Fr. Vincent Nichols, now Cardinal Archbishop of Westminster.

The coup de grace came when Arch. Patrick Kelly of Liverpool decided to close St. Joseph’s in 1996. The building, together with its grounds (where the mortal remains of Bishop O’Reilly and Bishop Keating, the two Prelates to whom St. Joseph’s Seminary owed its existence and development, had been buried), were sold to a development company in 2003.

St. Peter’s Seminary

Surrounded by acres of Scottish woodland, St. Peter’s Seminary, Cardross, is an example of Le Corbusier’s modernist, brutalist architecture. Built entirely in concrete – including its altars – it has the appearance of a multi-tiered car park or a post-WWII Soviet tenement building that fits with the communist ideology. The dystopian seminary was opened in 1966, buoyed up by the wave of optimism launched by Vatican II’s promise of a “New Springtime” for the Church. It closed 14 years later for lack of sufficient vocations, without ever having reached anything like it its intended capacity of 100 seminarians.

Garish ruins of St. Peter’s seminary

As a final irony, the modernist structure that was built to house a typically Vatican II-era generation of men and imbue them with a “naturalist,” this-worldly view of the priesthood, was itself overtaken by the forces of Nature: it was slowly but surely encroached by the surrounding woodland, eroded by the elements and subjected to the repeated depredations of vandals. The site, which has been long exposed to the scorn and derision of sightseers, reinforces the humiliation of the Catholic priesthood initiated at Vatican II. The last word can go to a writer who visited the devastated vineyard:

“As one descends a stone staircase littered with broken glass, there are yet visible many such altars, all in rows, altars that have long since fallen into disrepair. Today these altars are marked and defaced by obscene and macabre graffiti. The overall scene is a pitiful one; it is more Tarkovsky [a Russian film producer] than St. Thomas Aquinas.”6

Where the real fault in seminary closures lies

When the original founder of Upholland, Bishop O’Reilly, died, the 19th-century Liverpool priest, Fr. James Nugent, wrote that the seminary project had been “the cherished child of his heart, even to his last breath.”7

In a cruel and perverse fate, that child is no longer cherished by the clergy, because it was unloved, unsung and neglected by them when they collectively transferred their allegiance from Tradition to the revolutionary principles of Vatican II.

Vatican II’s contribution to the crisis in priestly identity

Just as it did with Matrimony, the Council inverted the ends of the priesthood; it accomplished this by placing far greater emphasis on the role of the priest as a service to man than to God. This broader vision left the way open to interpretations which included anything from gun-running in Latin America by priests and nuns, to clerical support for adultery and same-sex unions. The Council’s innovative doctrines encouraged the clergy and laity to adopt the cult of man over and above the cult of God, to prefer earthly considerations to heavenly realities, the profane to the sacred, the secular to the religious, and to exalt the laity over the clergy. As the Council sought a compromise between unchangeable doctrine and the anti-Christian theories of the modern world, the immutable principles of the Moral Law were subordinated to the free expression of modern man’s impulses and desires.

What is the priest? After Vatican II, the question is still up in the air

The Coadjutor Archbishop Thomas Murphy of Seattle asked this very question in 1988, but was still searching for an answer over 20 years after the Council’s Decree on the Ministry and life of Priests:

“The question – What is the priest? – is of tremendous significance today because when we are able to articulate a theology of the priesthood that is appropriated by the Christian community, then we will have a clearer idea of the direction of seminary education and formation today, in its task of preparing ordained leaders for the Church of tomorrow.”8

This is an admission that in the post-Vatican II Church even Bishops are still unsure of the answer. A radical shift from the transcendent to the mundane had taken place in the modern Church’s understanding of the sacramental priesthood, which was bound to impact on the kind of seminary training received by those seeking Ordination. The basic problem was that the meaning of the sacramental priesthood had been compromised by the Council’s technique of obfuscation (literally throwing into the shadow) of the priestly office of sacrifice, leading to confusion about the identity of the priest.

Modern priests & seminarians playing basketball:

a decisive turn towards worldliness

It cannot be denied that the differences between the two systems of seminary formation – pre- and post-Vatican II – outlined in this article could not be starker; nor could those between how priests perceived themselves and their mission before and after Vatican II be more evident. The Council, then, can be seen as a point of inflection in the history of the post-Conciliar Church that would determine the course of future developments in the area of priestly vocations.

Continued

- Quoted in David W. Atherton and Michael P. Peyton, St Joseph's College, Upholland, Lancashire, One of the glories of Catholicism in England: Its rise and fall, 2013, p. 18.

- Peter Doyle, Upholland College: One Hundred and Fifty Years of Priestly Training, Wigan: North West Catholic History Society, 2018.

- Archbishop Richard Downey, Lenten Pastoral Letter, 1934.

- Kevin Kelly, ‘A Rich Vatican II Resource’, The Furrow, vol. 65, n. 9, September 2014, p. 439.

- Dublin: Columba Press, 2012.

- K. V. Turley, National Catholic Register, January 18, 2021.

- Thomas Burke, Catholic History of Liverpool, Liverpool: C. Tinling, 1910, p. 236.

- Thomas Murphy, ‘Forces Shaping the Future of Seminaries’, Origins, vol. 17, n. 37, February 25, 1988, p. 637.

Posted December 6, 2023

______________________

______________________

Volume I |

Volume II |

Volume III |

Volume IV |

Volume V |

Volume VI |

Volume VII |

Volume VIII |

Volume IX |

Volume X |

Volume XI |

Special Edition |