Traditionalist Issues

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Dialogue Mass - XX

A Reform Imposed Despite

Opposition from the Majority of the Bishops

Having given Bugnini free rein to influence the reform of the Holy Week rites against the judgement of many of the world’s Bishops, Pius XII further increased his scope for liturgical mayhem by appointing him as a Consulter to the Congregation of Rites in 1956. True to form, Bugnini went about his task in predictable fashion, like a self-propelled, guided missile which, was directed by the masters of Progressivism to accomplish their long-planned agenda.

He immediately set in motion plans to bring about further changes to the Roman Breviary which Pius XII had allowed him to decimate in 1955 on the excuse of greater “simplification.” (1)

He immediately set in motion plans to bring about further changes to the Roman Breviary which Pius XII had allowed him to decimate in 1955 on the excuse of greater “simplification.” (1)

In 1957, the Congregation of Rites again consulted the world’s Bishops about further liturgical changes. But this time Bugnini’s “explosion of joy” turned out to be the dampest of squibs. The archival records of the Congregation show that the majority of Bishops wanted the status quo of the Divine Office to be preserved intact. One Bishop is reported to have declared that he was representative of the “large number” (92% as it was recorded), (2) of Bishops who were satisfied with the Breviary as it was and who also considered any change not only undesirable but dangerous to the Church. He even quoted St. Thomas Aquinas (Summa, I-II, q. 97, art. 2) on the harmful consequences that are likely to ensue when laws are changed, adding: “It is not easy to say ‘no’ to requests for change, but that is the proper action here.” (3)

This is a statement of great significance. A Bishop – representing the large majority at that time – had, to his great credit, dared to assert the over-riding importance of defending liturgical traditions at a time when the progressivists were teaching contempt for and even hostility towards them.

Maxima Redemptionis: a departure from Tradition

It is noteworthy that the Holy Week reforms were regarded in their day as out of the usual course of papal acts, an aberration in the history of liturgical tradition. One of the foremost members of the Liturgical Movement, Fr. Frederick McManus, commented approvingly in 1956:

It is noteworthy that the Holy Week reforms were regarded in their day as out of the usual course of papal acts, an aberration in the history of liturgical tradition. One of the foremost members of the Liturgical Movement, Fr. Frederick McManus, commented approvingly in 1956:

“Certainly the changes now commanded by the Apostolic See are extraordinary, particularly since they come after nearly four centuries of little liturgical development.” (4)

We should not underestimate the magnitude of these changes that included outright novelties such as “active participation,” use of the vernacular, the priest facing the people and invasion of the sanctuary by the laity. Taken together, they represented a major shift in the liturgy of the Church.

Continuity broken

It was the perennial teaching of the Church regarding its lex orandi that the preservation of liturgical tradition was an indispensable means to safeguard the integrity of Catholic doctrine. Yet the Congregation of Rites under Pius XII was issuing Decrees and Instructions promoting substantial changes to the Holy Week ceremonies whose texts, rubrics and ceremonial traditions proclaimed and transmitted the orthodox Catholic Faith.

But, it was not just the changes to the rites of Holy Week that broke the thread of continuity with the past. More fundamentally, it was the conscious attempt by the progressivists to reinvent the liturgy and their deliberate plan to inculcate their own desired values at odds with Tradition. Although the liturgy should be beyond the manipulation of any individual or group, in the Holy Week reforms the progressivist viewpoint prevailed. In an unprecedented abdication of papal responsibility, Pius XII allowed the radical members of the Liturgical Movement to impose their will on the rest of the Church.

A Rubicon too far

With the Holy Week reforms, a Rubicon had been crossed. History furnishes an interesting parallel between the army of Julius Caesar which crossed the Rubicon in 49 B.C. and the members of the Liturgical Movement (at whose behest Pius XII made the reforms). Just as crossing the river was an act that ended in civil war within Rome, so the Holy Week reforms crossed the boundaries of Tradition and would eventually split the faithful into warring camps. Both acts were pivotal events in history that committed the people involved to a specific course. (5)

It seems that Pius XII had not heeded his Predecessor’s teaching regarding the responsibilities of Popes towards the liturgy. In effect, Pius XI, in his Bull Divini Cultus of December 10, 1928, declared:

It seems that Pius XII had not heeded his Predecessor’s teaching regarding the responsibilities of Popes towards the liturgy. In effect, Pius XI, in his Bull Divini Cultus of December 10, 1928, declared:

“No wonder then, that the Roman Pontiffs have been so solicitous to safeguard and protect the liturgy. They have used the same care in making laws for the regulation of the liturgy, in preserving it from adulteration, as they have in giving accurate expression to the dogmas of the faith.”

It cannot be argued, however, that Pius XII used the same care in making liturgical laws. Having once warned about the “suicide of altering the Faith in the liturgy,” he nonetheless failed to preserve the Holy Week liturgy from adulteration and contamination by alien elements which could – and did – lead many to a false understanding of doctrine.

Disowning the past

Furthermore, the acceptance of liturgical change had many other deleterious effects. It cast a shadow of criticism on the Holy Week rites of previous centuries, and even on those Bishops and priests who had been faithfully celebrating them during the reign of Pius XII. With the Pope giving his support to Bugnini, they were left open to criticism as being “insensitive” to the aspirations of the laity, guilty of injustice and, in a word, “unpastoral.” As events have shown, they were dismissed as hopelessly hidebound conservatives standing in the way of progress and modernity. Their authority would be undermined and, as St. Thomas warned in such cases, discipline would be shaken, leading to calls for far more radical changes in the future.

Legitimating dissent

The imposition of the Holy Week reforms encouraged dissent and contempt for the law because the Pope was seen to acquiesce with those who had been acting against liturgical law for decades before Maxima Redemptionis. In spite of his warning that no one should introduce unauthorized innovations into the liturgy, his acquiescence in widespread dissent was an encouragement for the progressivists to commit further violations in the expectation that the official Church would eventually “catch up” with them once again.

Another unfortunate consequence of Pope Pius XII’s decision to reform the Holy Week ceremonies was that the disobedience of those who implemented the changes before they were approved, and who promoted still further changes, was tolerated in principle. Once this was done with something as sacred as the liturgy, and on the basis of a set of opinions prevalent in the Liturgical Movement, the signal was given that other changes considered urgent or “pastoral” could also be made on some trumped-up pretext. (6)

What this meant in practice was that the authority of both the liturgy and tradition was weakened in proportion as it was placed at the service of a principle of Progressivism – that of “active participation.” And it was Progressivism that would find its ultimate triumph in Vatican II’s Constitution Sacrosanctum Concilium on the Liturgy.

In the Holy Week reforms we can see clearly taking shape the ground plan for more far-reaching mutations not only in Catholic worship but also in theology and the concept of the priesthood.

Continued

In the 1930s a High Mass of Bishop Shaughnessy from Seattle, Washington, seated in the cathedra in the background; Archbishop Howard of Portland, Oregon, in the foreground with train bearers - a splendid liturgical ceremonial destroyed by Bugnini

In 1957, the Congregation of Rites again consulted the world’s Bishops about further liturgical changes. But this time Bugnini’s “explosion of joy” turned out to be the dampest of squibs. The archival records of the Congregation show that the majority of Bishops wanted the status quo of the Divine Office to be preserved intact. One Bishop is reported to have declared that he was representative of the “large number” (92% as it was recorded), (2) of Bishops who were satisfied with the Breviary as it was and who also considered any change not only undesirable but dangerous to the Church. He even quoted St. Thomas Aquinas (Summa, I-II, q. 97, art. 2) on the harmful consequences that are likely to ensue when laws are changed, adding: “It is not easy to say ‘no’ to requests for change, but that is the proper action here.” (3)

This is a statement of great significance. A Bishop – representing the large majority at that time – had, to his great credit, dared to assert the over-riding importance of defending liturgical traditions at a time when the progressivists were teaching contempt for and even hostility towards them.

Maxima Redemptionis: a departure from Tradition

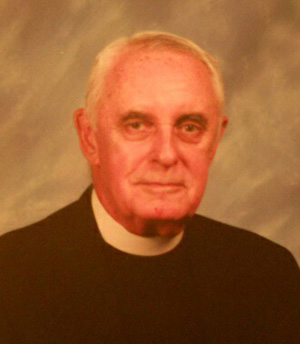

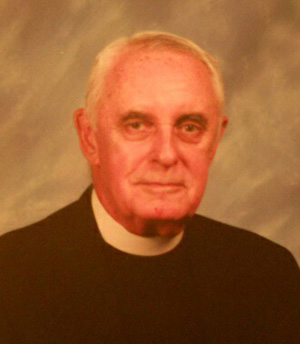

Fr. Frederick R. McManus

“Certainly the changes now commanded by the Apostolic See are extraordinary, particularly since they come after nearly four centuries of little liturgical development.” (4)

We should not underestimate the magnitude of these changes that included outright novelties such as “active participation,” use of the vernacular, the priest facing the people and invasion of the sanctuary by the laity. Taken together, they represented a major shift in the liturgy of the Church.

Continuity broken

It was the perennial teaching of the Church regarding its lex orandi that the preservation of liturgical tradition was an indispensable means to safeguard the integrity of Catholic doctrine. Yet the Congregation of Rites under Pius XII was issuing Decrees and Instructions promoting substantial changes to the Holy Week ceremonies whose texts, rubrics and ceremonial traditions proclaimed and transmitted the orthodox Catholic Faith.

But, it was not just the changes to the rites of Holy Week that broke the thread of continuity with the past. More fundamentally, it was the conscious attempt by the progressivists to reinvent the liturgy and their deliberate plan to inculcate their own desired values at odds with Tradition. Although the liturgy should be beyond the manipulation of any individual or group, in the Holy Week reforms the progressivist viewpoint prevailed. In an unprecedented abdication of papal responsibility, Pius XII allowed the radical members of the Liturgical Movement to impose their will on the rest of the Church.

A Rubicon too far

With the Holy Week reforms, a Rubicon had been crossed. History furnishes an interesting parallel between the army of Julius Caesar which crossed the Rubicon in 49 B.C. and the members of the Liturgical Movement (at whose behest Pius XII made the reforms). Just as crossing the river was an act that ended in civil war within Rome, so the Holy Week reforms crossed the boundaries of Tradition and would eventually split the faithful into warring camps. Both acts were pivotal events in history that committed the people involved to a specific course. (5)

Julius Caesar crossing the Rubicon

“No wonder then, that the Roman Pontiffs have been so solicitous to safeguard and protect the liturgy. They have used the same care in making laws for the regulation of the liturgy, in preserving it from adulteration, as they have in giving accurate expression to the dogmas of the faith.”

It cannot be argued, however, that Pius XII used the same care in making liturgical laws. Having once warned about the “suicide of altering the Faith in the liturgy,” he nonetheless failed to preserve the Holy Week liturgy from adulteration and contamination by alien elements which could – and did – lead many to a false understanding of doctrine.

Disowning the past

Furthermore, the acceptance of liturgical change had many other deleterious effects. It cast a shadow of criticism on the Holy Week rites of previous centuries, and even on those Bishops and priests who had been faithfully celebrating them during the reign of Pius XII. With the Pope giving his support to Bugnini, they were left open to criticism as being “insensitive” to the aspirations of the laity, guilty of injustice and, in a word, “unpastoral.” As events have shown, they were dismissed as hopelessly hidebound conservatives standing in the way of progress and modernity. Their authority would be undermined and, as St. Thomas warned in such cases, discipline would be shaken, leading to calls for far more radical changes in the future.

Legitimating dissent

The imposition of the Holy Week reforms encouraged dissent and contempt for the law because the Pope was seen to acquiesce with those who had been acting against liturgical law for decades before Maxima Redemptionis. In spite of his warning that no one should introduce unauthorized innovations into the liturgy, his acquiescence in widespread dissent was an encouragement for the progressivists to commit further violations in the expectation that the official Church would eventually “catch up” with them once again.

Another unfortunate consequence of Pope Pius XII’s decision to reform the Holy Week ceremonies was that the disobedience of those who implemented the changes before they were approved, and who promoted still further changes, was tolerated in principle. Once this was done with something as sacred as the liturgy, and on the basis of a set of opinions prevalent in the Liturgical Movement, the signal was given that other changes considered urgent or “pastoral” could also be made on some trumped-up pretext. (6)

What this meant in practice was that the authority of both the liturgy and tradition was weakened in proportion as it was placed at the service of a principle of Progressivism – that of “active participation.” And it was Progressivism that would find its ultimate triumph in Vatican II’s Constitution Sacrosanctum Concilium on the Liturgy.

In the Holy Week reforms we can see clearly taking shape the ground plan for more far-reaching mutations not only in Catholic worship but also in theology and the concept of the priesthood.

Continued

- See the General Decree Cum Nostra Hac Aetate, AAS, 23 March 1955, p. 218, which brought about changes in the rubrics of the Roman Missal and the Breviary in the direction of greater “simplification.” This consisted mainly of eliminating most of the octaves and vigils from the Roman Calendar. Of the 18 octaves in use before 1955, all but three (Easter, Pentecost, Christmas) were purged in the reform, including the octaves of the Epiphany, Corpus Christi, the Ascension and the Immaculate Conception. Approximately half of the vigils disappeared in the reform. The Our Father, Hail Mary and Creed recited at the beginning of each liturgical hour were abolished; likewise the final Antiphon to Our Lady, except at Compline. Bugnini, who had masterminded the project, had no compunction about his role. See Annibale Bugnini, The Simplification of the Rubrics, Trans. L. J. Doyle, Collegeville: Doyle and Finegan, 1955.

- Jul 29, 1957, Sacred Congregation of Rites, Historical Section, Memoria, supplement IV, Consultation of the Episcopate concerning a reform of the Roman Breviary: Results and Conclusions, p. 36, apud Thomas Richstatter OFM, Liturgical Law. New Style, New Spirit, Chicago: Franciscan Herald Press, 1977, p. 40. It is interesting to note that only 8% of the Bishops wanted the Breviary to be changed, which in all probability corresponds to the percentage of Bishops supporting the aims of the Liturgical Movement. The same source reveals that only 17% of the Bishops asked permission for the use of the vernacular at least in some parts of the Breviary; they were massively outnumbered by those who explicitly asked for Latin to be retained for the sake of the priesthood. (ibid., p. 39)

- Jul 29, 1957, Sacred Congregation of Rites, Historical Section, Memoria, pp. 101-2, apud Thomas Richstatter, Liturgical Law. New Style, New Spirit, pp. 40-41

- Frederick McManus, The Rites of Holy Week: Ceremonies, Preparation, Music, Commentaries, Paterson, New Jersey: St Anthony Guild Press,1956, p. v.

- The Rubicon was also the place where Caesar is said to have uttered the famous phrase “alea iacta est” (the die is cast), meaning that the situation he created was irreversible.

- These would not be confined to the liturgy but could embrace “new understandings” of the Faith, the Church, other religions, marriage and family life, human needs etc.

Posted May 18, 2015

______________________

______________________

Volume I |

Volume II |

Volume III |

Volume IV |

Volume V |

Volume VI |

Volume VII |

Volume VIII |

Volume IX |

Volume X |

Volume XI |

Special Edition |