Traditionalist Issues

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Dialogue Mass - LXXV

Endless Abuses of ‘Active Participation’

It is worth remembering that for ecclesiastic documents – magisterial, liturgical and legal – the Latin version was always the normative one. Only the Latin text of Pius X’s Code of Canon Law, (1) for example, had force of law. The same applies to his motu proprio which describes itself as a “juridical code of sacred music” issued for the universal Church with the “fullness of Our Apostolic Authority” and having “the “force of law.”

Latin rather than any vernacular version assures accuracy in the transmission and correct understanding of information. It follows that, where there are discrepancies between the Latin and vernacular, the corresponding Latin version predominates.

Latin rather than any vernacular version assures accuracy in the transmission and correct understanding of information. It follows that, where there are discrepancies between the Latin and vernacular, the corresponding Latin version predominates.

A rigorous study of Tra le sollecitudini (TLS) would confirm that it is riddled with ambiguities, nuances and concepts not found in the Latin text. So, those unwise enough to rely on the various vernacular interpretations of TLS have only second- third- and-fourth-hand corruptions of the Latin, with each version diverging further from the original.

It is not difficult to envisage how the liturgical reforms have been affected by decades of linguistic misunderstanding on the part of Pastors who had never consulted the normative Latin source, and who were dependent on corrupted translations. They simply relied on whatever the progressivist reformers had told them. As a result, “active participation” was eventually taken for granted by all Novus Ordo priests, despite its capacity to overthrow the objective liturgical tradition and the rubrical framework that held it firmly in place.

Such a system has the obvious potential to be exploited in order to meet the reformers’ perceptions of the “good of the Church” – a phrase used in Sacrosanctum Concilium (§ 23) as an excuse to introduce “innovations.” But without accurate information, how could those responsible for liturgical reforms make sound decisions consonant with the Church’s self-understanding?

Exegesis or eisegesis?

Reliance on faulty translations was never the practice in any area of ecclesiastical life before Pius XII’s reforms. Traditionally, the Church used a method of interpretation known as exegesis, which draws out of the Latin text the meaning its author meant to convey.

On the other hand, there is the method called eisegesis, whereby the translator introduces his own presuppositions and biases into the text by “seeing” what he wishes to find in it, e.g. “actuosa” (active). This involves reading into the text what is not there.

As we have seen, this is exactly what happened to certain passages in Tra le sollecitudini, the most egregious example being the following:

As we have seen, this is exactly what happened to certain passages in Tra le sollecitudini, the most egregious example being the following:

“To restore the use of Gregorian Chant by the people, so that the faithful may again take a more active part in the ecclesiastical offices, as was the case in ancient times.”

This was the preferred method of the liturgical reformers who set out to “prove” what were really only their own subjective notions and pre-held agenda for “active participation.” Even today, they obsess so much about the word “active” that they miss the whole point of the motu proprio.

It is understandable that actuosa (active) was not used in the Latin version of the motu proprio for the following reasons.

First, because the word lends itself to a vague and general interpretation: Its very fluidity would have made the application of the law not only problematic in its own day, but also subject to a broad interpretation by future lawmakers.

And indeed, as recent history has shown, the range of possible interpretations of “active participation” is limitless and continues to expand exponentially. Nor is it possible to contain or control its expansion without nullifying Article 14 of the Liturgy Constitution, which declared “active participation” to be the overriding goal to which all other considerations are subordinated.

The principle of relativism

Second, “active participation” is based on a falsehood, the principle of relativism, whereby the liturgy handed down through the centuries is adapted to the subjective and changing perceptions of the people participating. These vary from parish to parish, from one Novus Ordo Mass to another, depending on how each Liturgy Committee assesses a particular group’s cultural norms and values.

Although few could have realized it in 1963, this was the fundamental import of §19 of the Liturgy Constitution, (2) which, of course, spelt the end for the objective Liturgical Tradition

A question of logic

To illustrate the point, we will make use of the Medieval adage, ex falso quodlibet (“from a falsehood, anything follows”), meaning that once a contradiction is admitted as truth, any conclusion, however nonsensical, can logically be derived from it.

As an aside, we can see how this worked in practice as a direct result of the false principles ‒ “opening to the world,” “ecumenism” etc. ‒ introduced by Vatican II in contradiction to the Church’s Tradition. The ensuing toll of destruction speaks for itself.

When applied to the Novus Ordo liturgy, this principle explains the logical underpinnings of the regime of novelty. Once “active participation” is accepted as an authentic and indispensable method of lay involvement in the liturgy, any activity – no matter how inappropriate, sacrilegious or offensive to morals – flows logically from the false premise.

When applied to the Novus Ordo liturgy, this principle explains the logical underpinnings of the regime of novelty. Once “active participation” is accepted as an authentic and indispensable method of lay involvement in the liturgy, any activity – no matter how inappropriate, sacrilegious or offensive to morals – flows logically from the false premise.

Even though the logic of the liturgical reforms makes sense within its own terms of reference, its starting point (“active participation”) was wrong. So, its conclusions (the practical consequences as evidenced in the Novus Ordo Masses) were also wrong in spite of the correctness of its logic or, rather, because of it.

The truth of this adage was demonstrated by St. Thomas More in the 16th century in one of his polemical treatises against the Protestant reformers who had rejected the doctrine of the Real Presence and changed their liturgies to suit. When William Tyndale mocked some of the Church’s traditional rituals as superstitious practices, More replied that anyone capable of deriding the way devout Catholics worshipped over the centuries is also likely to disdain the Eucharist Itself. (3)

This principle also explains why so many Churchmen see nothing at all amiss with the routine irreverence displayed during the liturgy, especially to the Eucharistic Presence, and do not “see” the most outrageous examples of profanation, even though they hit you right in the eye. These are the inevitable outcomes of the all-encompassing directive of Vatican II’s Liturgy Constitution, which makes “active participation” the primary consideration of the liturgy. Those who enact it are, after all, only obeying the logic of the reforms and are convinced they are perfectly correct.

Thus, the root of the present crisis in the liturgy can be traced to that single word “active,” which was first slipped into the vernacular version of TLS and was reiterated in subsequent magisterial documents. Because it stood in contradiction to Tradition ‒ in fact, it was expressly intended by the progressivists to stamp out the contemplative and devotional dimension of worship that provided a sense of reverence and awe – it had the effect of causing the entire logical framework of the lex orandi to “explode.” (4)

Providentially, there is no such tripwire in the Latin motu proprio of Pius X.

The logic of true participation

But the traditional Roman Rite, which had withstood the test of time and was fine-tuned to be quintessentially Catholic, had a logic of its own, which was understood (alas, this is no longer the case) by all practicing Catholics, no matter what century they lived in.

St. Thomas More explained it thus:

“Good folk find this indeed, that when they be at the divine service in the church, the more devoutly that they see such godly ceremonies observed, and the more solemnity that they see therein, the more devotion feel they themselves therewith in their own souls.” (5)

That was precisely the logic of Pius X’s motu proprio. In the Introduction the Pope singled out from among his many concerns the one that was of the greatest importance: (6) to promote the “decorum of the house of God” and the solemnity and splendour of the ceremonies. Therefore, he said, nothing should take place that would disturb or diminish the prayer and piety of the faithful who participated by drawing spiritual sustenance from the actions of the priest and his ministers in the sanctuary.

That was precisely the logic of Pius X’s motu proprio. In the Introduction the Pope singled out from among his many concerns the one that was of the greatest importance: (6) to promote the “decorum of the house of God” and the solemnity and splendour of the ceremonies. Therefore, he said, nothing should take place that would disturb or diminish the prayer and piety of the faithful who participated by drawing spiritual sustenance from the actions of the priest and his ministers in the sanctuary.

This was the reality of lay participation experienced by countless Catholics for centuries, before the Liturgical Movement discredited the practice and reviled the faithful as “silent spectators.”

Fr. J. D. Crichton, one of the most virulent opponents of silent participation, taking his cue from the Liturgy Constitution, stated: “The Mass does not fully manifest the intention of the Church if the baptized members of the congregation remain silent.” (7)

But then, as far as the liturgical reformers were concerned, the question of fidelity to Tradition was academic. Neither ethics nor truth was required, simply the strong arm of the law.

But, where is the logic in funding one’s own destruction?

Continued

Only the Latin texts of documents - e.g. the 1917 Code of Canon Law - had the full force of law

A rigorous study of Tra le sollecitudini (TLS) would confirm that it is riddled with ambiguities, nuances and concepts not found in the Latin text. So, those unwise enough to rely on the various vernacular interpretations of TLS have only second- third- and-fourth-hand corruptions of the Latin, with each version diverging further from the original.

It is not difficult to envisage how the liturgical reforms have been affected by decades of linguistic misunderstanding on the part of Pastors who had never consulted the normative Latin source, and who were dependent on corrupted translations. They simply relied on whatever the progressivist reformers had told them. As a result, “active participation” was eventually taken for granted by all Novus Ordo priests, despite its capacity to overthrow the objective liturgical tradition and the rubrical framework that held it firmly in place.

Such a system has the obvious potential to be exploited in order to meet the reformers’ perceptions of the “good of the Church” – a phrase used in Sacrosanctum Concilium (§ 23) as an excuse to introduce “innovations.” But without accurate information, how could those responsible for liturgical reforms make sound decisions consonant with the Church’s self-understanding?

Exegesis or eisegesis?

Reliance on faulty translations was never the practice in any area of ecclesiastical life before Pius XII’s reforms. Traditionally, the Church used a method of interpretation known as exegesis, which draws out of the Latin text the meaning its author meant to convey.

On the other hand, there is the method called eisegesis, whereby the translator introduces his own presuppositions and biases into the text by “seeing” what he wishes to find in it, e.g. “actuosa” (active). This involves reading into the text what is not there.

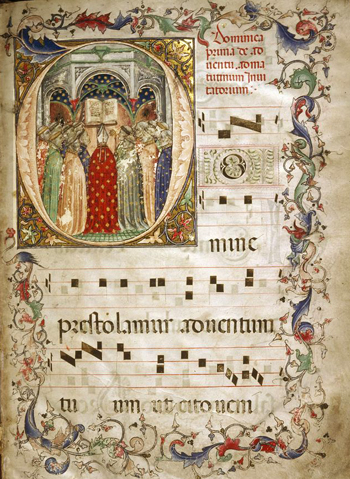

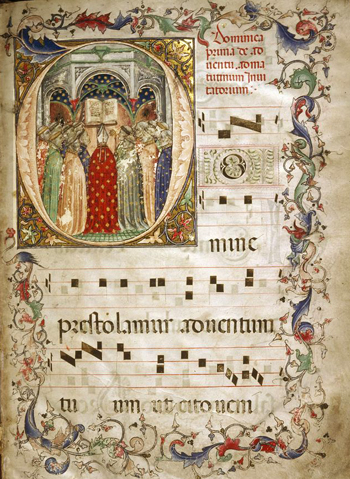

A medieval manuscript depicts clerics grouped around the Bishop at a holy service

“To restore the use of Gregorian Chant by the people, so that the faithful may again take a more active part in the ecclesiastical offices, as was the case in ancient times.”

This was the preferred method of the liturgical reformers who set out to “prove” what were really only their own subjective notions and pre-held agenda for “active participation.” Even today, they obsess so much about the word “active” that they miss the whole point of the motu proprio.

It is understandable that actuosa (active) was not used in the Latin version of the motu proprio for the following reasons.

First, because the word lends itself to a vague and general interpretation: Its very fluidity would have made the application of the law not only problematic in its own day, but also subject to a broad interpretation by future lawmakers.

And indeed, as recent history has shown, the range of possible interpretations of “active participation” is limitless and continues to expand exponentially. Nor is it possible to contain or control its expansion without nullifying Article 14 of the Liturgy Constitution, which declared “active participation” to be the overriding goal to which all other considerations are subordinated.

The principle of relativism

Second, “active participation” is based on a falsehood, the principle of relativism, whereby the liturgy handed down through the centuries is adapted to the subjective and changing perceptions of the people participating. These vary from parish to parish, from one Novus Ordo Mass to another, depending on how each Liturgy Committee assesses a particular group’s cultural norms and values.

Although few could have realized it in 1963, this was the fundamental import of §19 of the Liturgy Constitution, (2) which, of course, spelt the end for the objective Liturgical Tradition

A question of logic

To illustrate the point, we will make use of the Medieval adage, ex falso quodlibet (“from a falsehood, anything follows”), meaning that once a contradiction is admitted as truth, any conclusion, however nonsensical, can logically be derived from it.

As an aside, we can see how this worked in practice as a direct result of the false principles ‒ “opening to the world,” “ecumenism” etc. ‒ introduced by Vatican II in contradiction to the Church’s Tradition. The ensuing toll of destruction speaks for itself.

From the opening comes every aberration, like the beach Mass, above, and its choir, below

Even though the logic of the liturgical reforms makes sense within its own terms of reference, its starting point (“active participation”) was wrong. So, its conclusions (the practical consequences as evidenced in the Novus Ordo Masses) were also wrong in spite of the correctness of its logic or, rather, because of it.

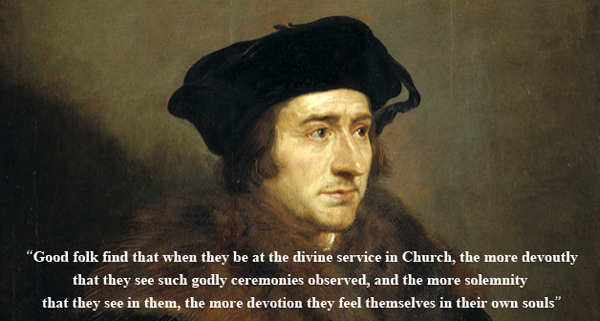

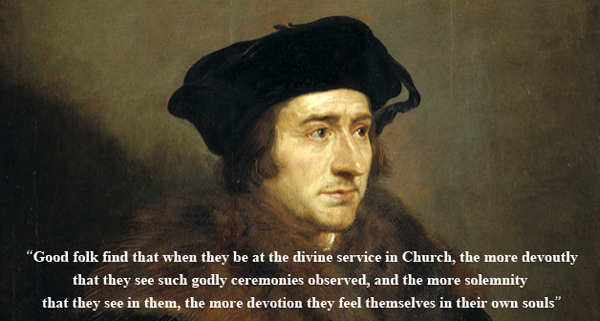

The truth of this adage was demonstrated by St. Thomas More in the 16th century in one of his polemical treatises against the Protestant reformers who had rejected the doctrine of the Real Presence and changed their liturgies to suit. When William Tyndale mocked some of the Church’s traditional rituals as superstitious practices, More replied that anyone capable of deriding the way devout Catholics worshipped over the centuries is also likely to disdain the Eucharist Itself. (3)

This principle also explains why so many Churchmen see nothing at all amiss with the routine irreverence displayed during the liturgy, especially to the Eucharistic Presence, and do not “see” the most outrageous examples of profanation, even though they hit you right in the eye. These are the inevitable outcomes of the all-encompassing directive of Vatican II’s Liturgy Constitution, which makes “active participation” the primary consideration of the liturgy. Those who enact it are, after all, only obeying the logic of the reforms and are convinced they are perfectly correct.

Thus, the root of the present crisis in the liturgy can be traced to that single word “active,” which was first slipped into the vernacular version of TLS and was reiterated in subsequent magisterial documents. Because it stood in contradiction to Tradition ‒ in fact, it was expressly intended by the progressivists to stamp out the contemplative and devotional dimension of worship that provided a sense of reverence and awe – it had the effect of causing the entire logical framework of the lex orandi to “explode.” (4)

Providentially, there is no such tripwire in the Latin motu proprio of Pius X.

The logic of true participation

But the traditional Roman Rite, which had withstood the test of time and was fine-tuned to be quintessentially Catholic, had a logic of its own, which was understood (alas, this is no longer the case) by all practicing Catholics, no matter what century they lived in.

St. Thomas More explained it thus:

“Good folk find this indeed, that when they be at the divine service in the church, the more devoutly that they see such godly ceremonies observed, and the more solemnity that they see therein, the more devotion feel they themselves therewith in their own souls.” (5)

St. Thomas More emphasizes the need for solemnity

This was the reality of lay participation experienced by countless Catholics for centuries, before the Liturgical Movement discredited the practice and reviled the faithful as “silent spectators.”

Fr. J. D. Crichton, one of the most virulent opponents of silent participation, taking his cue from the Liturgy Constitution, stated: “The Mass does not fully manifest the intention of the Church if the baptized members of the congregation remain silent.” (7)

But then, as far as the liturgical reformers were concerned, the question of fidelity to Tradition was academic. Neither ethics nor truth was required, simply the strong arm of the law.

But, where is the logic in funding one’s own destruction?

Continued

- The Pio-Benedictine Codex Juris Canonici (1917) was drawn up by Pius X and promulgated by Benedict XVI.

- “With zeal and patience, pastors of souls must promote the liturgical instruction of the faithful, and also their active participation in the liturgy both internally and externally, taking into account their age and condition, their way of life, and standard of religious culture.” [emphasis added]

- St. Thomas More, The Confutation of Tyndale’s Answer, in The Complete Works of St Thomas More, ed. Louis Schuster et al, vol. 8, book 1, New Haven: Yale University Press, 1973, p. 111.

- Ex falso quodlibet is also called “the principle of explosion.”

- St. Thomas More, ibid., vol. 8, book 2, p. 161.

- The English mistranslation refers to this concern as “a leading one,” implying that there were others of the same ranking, such as “active participation,” but Pius X had left no room for equivocation: “illa principem tenet locum” (this one holds the highest place).

- J. D. Crichton, The Church’s Worship: Considerations on the Liturgical Constitution of the Second Vatican Council, New York: Sheed and Ward, 1964, pp. 68-69.

Posted August 29, 2018

______________________

______________________

Volume I |

Volume II |

Volume III |

Volume IV |

Volume V |

Volume VI |

Volume VII |

Volume VIII |

Volume IX |

Volume X |

Volume XI |

Special Edition |