Traditionalist Issues

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Dialogue Mass - LXXXVIII

St. Michael: Another ‘Unwanted’ Feast

for the Reformers

Another example of the arbitrary and oppressive nature of what Mgr. Bugnini called “simplification” of the Calendar is the suppression in 1960 of a feast of major importance in the life of the Church: the Apparition of St. Michael (May 8).

For centuries before 1960, there were two feasts of St. Michael in the Universal Calendar: May 8 and September 29. But they were designated by the Liturgical Commission as an unnecessary “duplication,” and the Apparition of St. Michael was thrown out along with the other “unwanted” feasts in the 1960 Calendar.

As with the previously mentioned feasts eliminated in the same year, it involved the building of a place of worship to commemorate miraculous events. According to the Roman Breviary, the feast was instituted to thank God for a military victory achieved at Monte Gargano, Italy, on May 8 , 663, through the intercession of St. Michael. The battle was described by the 8th century Benedictine historian, Paul the Deacon, thus:

As with the previously mentioned feasts eliminated in the same year, it involved the building of a place of worship to commemorate miraculous events. According to the Roman Breviary, the feast was instituted to thank God for a military victory achieved at Monte Gargano, Italy, on May 8 , 663, through the intercession of St. Michael. The battle was described by the 8th century Benedictine historian, Paul the Deacon, thus:

“When the Greeks of that time came to plunder the sanctuary of the holy Archangel [Michael] situated upon Mount Garganus (Gargano), Grimuald [King of the Lombards], coming upon them with his army, overthrew them with much slaughter.” (1)

What is remarkable about this incident is that the Archangel had promised to protect the sanctuary – now the oldest shrine in the West dedicated to St. Michael – when he appeared there in 492.

The pre-1960 Breviary gives a full account of the circumstances. (2) From this we learn that St. Michael appeared at the end of the 5th century to the Bishop of the nearby town of Siponto, with a message concerning a cave in Monte Gargano: (3) namely, that the grotto should become a shrine dedicated to St. Michael who would take it under his protection.

However, as such miraculous occurrences simply have no meaning in progressist circles of the Catholic Church, Bugnini dismissed them as “not historical,” implying that they were not worthy of credibility. Instead, liturgical “experts” have chosen to believe something of their own invention: that the Apparition of St. Michael, like many other “second feasts” of an individual Saint, was cluttering up the Liturgical Year, and should no longer occupy a place in the General Calendar.

We cannot overlook the underlying reason for the feast’s removal. By 1960, the Church was beginning to downplay the supernatural character of the liturgy to make it more acceptable to Protestants, who rejected miracles and apparitions.

We cannot overlook the underlying reason for the feast’s removal. By 1960, the Church was beginning to downplay the supernatural character of the liturgy to make it more acceptable to Protestants, who rejected miracles and apparitions.

Martin Luther had launched the absurd rumor that, during his Apparition, St. Michael had shed some of his feathers, which were being sought as “collectibles” by Catholic relic-hunters. (4)

The tale of the feathers so tickled the Protestant fancy that it is still provoking hilarity today. Mention the Apparition of St. Michael, and you are likely to be asked if you have a feather. It is even doing the rounds among Catholic liturgists (5) and priests who, in their homilies, wish to mock traditional beliefs.

We need only a brief look at the history of this feast and its reception by the Church up to 1960 to see how shocking these pretexts are in their spiritual obtuseness.

How important was the feast of the Apparition of St. Michael?

The importance of this feast derives from its place in History. (6)

First, it commemorates the first of several known apparitions of St. Michael the Archangel in Western Christianity, (7) and would play a seminal role in influencing the development of devotion to St. Michael in the Roman Rite.

Second, the shrine at Gargano was a major pilgrimage site of international status throughout the Middle Ages and, together with Jerusalem, was regarded as one of the holiest sites in Christendom. It was sometimes used as a staging post for pilgrims en route to Jerusalem by sea. It was visited by Popes, Emperors (including Charlemagne), Kings and Queens, Bishops and Abbots, Saints, clergy and lay faithful seeking the protection of St. Michael against the forces of Satan and his minions.

Second, the shrine at Gargano was a major pilgrimage site of international status throughout the Middle Ages and, together with Jerusalem, was regarded as one of the holiest sites in Christendom. It was sometimes used as a staging post for pilgrims en route to Jerusalem by sea. It was visited by Popes, Emperors (including Charlemagne), Kings and Queens, Bishops and Abbots, Saints, clergy and lay faithful seeking the protection of St. Michael against the forces of Satan and his minions.

Third, Pope St. Pius V considered this ancient feast to be of such importance for the spiritual life of the faithful that he placed it in the Calendar of the Universal Church in1568. This was not an innovation: Pius V simply transmitted to posterity the feast that had been handed down over centuries, and gave it its title in Apparitione S. Michaelis, by which it was subsequently known.

We know that Pius V was particularly devoted to St. Michael because he had taken the name Michele when he entered the Dominican Order as a novice. Following his celestial patron, the Pope proved himself to be a defender of Christ’s Church on earth.

Fourth, since then, the universal character of devotion to St. Michael is further shown by the feasts, calendars and martyrologies, Masses and prayers, patronages, (8) pilgrimages, guilds and confraternities dedicated to him, and which were all in some way connected with the 5th century Apparition.

Decline in devotion to St. Michael started in 1960

When we think of the prominence of St. Michael in public worship before 1960, we can see when the worm began to enter the apple: with the reforms of Pope John XXIII.

Before 1960, St. Michael was invoked 7 times at Low Mass (9) and also at High Mass, (10) but two times less in both cases after 1960 with the suppression of the Confiteor before Communion.

He was mentioned 9 times on his feast day, May 8, including two references to him in the Propers of the Mass: one indirectly in the Offertory verse, (11) the other by name in the Postcommunion. (12) Thus, although these references remained in the September feast of St. Michael in the 1962 Missal, an extra opportunity for the whole Church to give liturgical honors to St. Michael was dropped from the Calendar when the May feast was suppressed.

He was mentioned 9 times on his feast day, May 8, including two references to him in the Propers of the Mass: one indirectly in the Offertory verse, (11) the other by name in the Postcommunion. (12) Thus, although these references remained in the September feast of St. Michael in the 1962 Missal, an extra opportunity for the whole Church to give liturgical honors to St. Michael was dropped from the Calendar when the May feast was suppressed.

The Prayer to St. Michael – a prayer of Exorcism – mandated after every Low Mass as part of the Leonine Prayers (13) – was already under threat of extinction by 1960. It had been on the agenda of every international Liturgical Conference in the 1950s for elimination. (See here)

It is not surprising, therefore, that by 1962 there were rules already in place allowing the omission of the Leonine Prayers after Low Mass on a wide range of occasions, some examples being:

The final farewell to St. Michael

Five years later, when the Consilium produced the Novus Ordo Mass, St. Michael was written out of the text. Only on his feast day of September 29 is his name mentioned as an option in the Lectionary, but even this concession is withdrawn if his feast falls on a Sunday. Moreover, the Prince of the Heavenly Host, pre-eminent in the Angelic Hierarchy, now shares a group-title for his feast day with the other Archangels.

Who would have thought in 1960 that the Archangel who protected the Israelites in the Old Testament and is the special protector of the Church would himself need protection against attempts by the Church to downgrade and ignore him?

Who would have thought in 1960 that the Archangel who protected the Israelites in the Old Testament and is the special protector of the Church would himself need protection against attempts by the Church to downgrade and ignore him?

Who would have thought that a Pope would have inaugurated this campaign against St. Michael who, according to Tradition, is the Guardian Angel of each of the Sovereign Pontiffs? (15)

Pope John XXIII once stated,that “we must have a lively and profound devotion to our own Guardian Angel… and never forget him,” (16) but his enthusiasm for St. Michael seems to have flown out of the window he famously opened when “ecumenism” loomed on the horizon.

‘Ecumenism’ strikes again

The feast of the Apparition of St. Michael was a particularly sensitive issue because it stood at the intersection between private revelation and public liturgy. The very idea of angelic intervention – that St. Michael should appear in person, give instructions to individuals or intervene in human affairs – is dismissed by Protestants and progressist Catholics as mythology.

This reform was part of the gradual secularization of the Faith. St. Michael had been kept in the forefront of the minds of the faithful through the liturgy for centuries, but from 1960 belief in these supernatural realities began to disappear from Catholic consciousness.

This reform was part of the gradual secularization of the Faith. St. Michael had been kept in the forefront of the minds of the faithful through the liturgy for centuries, but from 1960 belief in these supernatural realities began to disappear from Catholic consciousness.

Few Catholics nowadays have any awareness of the need to pray to St. Michael “to defend us in battle.” It is as if this strong, virile symbol of the Church Militant has been made redundant, having exchanged his sword for a white flag and adopted “dialogue” as a fig-leaf for surrender to the forces of evil.

Continued

For centuries before 1960, there were two feasts of St. Michael in the Universal Calendar: May 8 and September 29. But they were designated by the Liturgical Commission as an unnecessary “duplication,” and the Apparition of St. Michael was thrown out along with the other “unwanted” feasts in the 1960 Calendar.

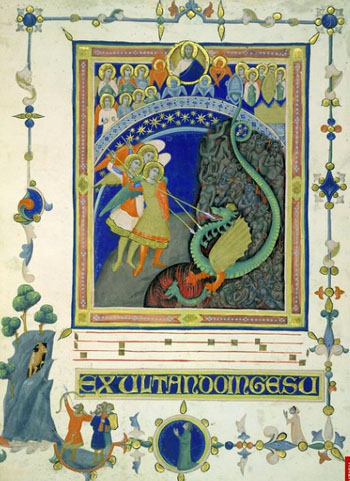

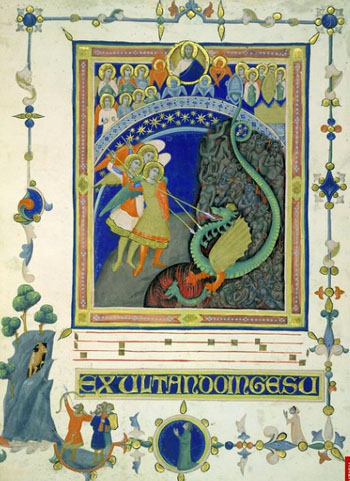

A medieval manuscript celebrates the victory of St. Michael at Monte Gargano

“When the Greeks of that time came to plunder the sanctuary of the holy Archangel [Michael] situated upon Mount Garganus (Gargano), Grimuald [King of the Lombards], coming upon them with his army, overthrew them with much slaughter.” (1)

What is remarkable about this incident is that the Archangel had promised to protect the sanctuary – now the oldest shrine in the West dedicated to St. Michael – when he appeared there in 492.

The pre-1960 Breviary gives a full account of the circumstances. (2) From this we learn that St. Michael appeared at the end of the 5th century to the Bishop of the nearby town of Siponto, with a message concerning a cave in Monte Gargano: (3) namely, that the grotto should become a shrine dedicated to St. Michael who would take it under his protection.

However, as such miraculous occurrences simply have no meaning in progressist circles of the Catholic Church, Bugnini dismissed them as “not historical,” implying that they were not worthy of credibility. Instead, liturgical “experts” have chosen to believe something of their own invention: that the Apparition of St. Michael, like many other “second feasts” of an individual Saint, was cluttering up the Liturgical Year, and should no longer occupy a place in the General Calendar.

The Sanctuary of Monte Gargano is the oldest shrine dedicated to St. Michael in Western Europe

Martin Luther had launched the absurd rumor that, during his Apparition, St. Michael had shed some of his feathers, which were being sought as “collectibles” by Catholic relic-hunters. (4)

The tale of the feathers so tickled the Protestant fancy that it is still provoking hilarity today. Mention the Apparition of St. Michael, and you are likely to be asked if you have a feather. It is even doing the rounds among Catholic liturgists (5) and priests who, in their homilies, wish to mock traditional beliefs.

We need only a brief look at the history of this feast and its reception by the Church up to 1960 to see how shocking these pretexts are in their spiritual obtuseness.

How important was the feast of the Apparition of St. Michael?

The importance of this feast derives from its place in History. (6)

First, it commemorates the first of several known apparitions of St. Michael the Archangel in Western Christianity, (7) and would play a seminal role in influencing the development of devotion to St. Michael in the Roman Rite.

St. Pius V was a great devotee of St. Michael the Archangel

Third, Pope St. Pius V considered this ancient feast to be of such importance for the spiritual life of the faithful that he placed it in the Calendar of the Universal Church in1568. This was not an innovation: Pius V simply transmitted to posterity the feast that had been handed down over centuries, and gave it its title in Apparitione S. Michaelis, by which it was subsequently known.

We know that Pius V was particularly devoted to St. Michael because he had taken the name Michele when he entered the Dominican Order as a novice. Following his celestial patron, the Pope proved himself to be a defender of Christ’s Church on earth.

Fourth, since then, the universal character of devotion to St. Michael is further shown by the feasts, calendars and martyrologies, Masses and prayers, patronages, (8) pilgrimages, guilds and confraternities dedicated to him, and which were all in some way connected with the 5th century Apparition.

Decline in devotion to St. Michael started in 1960

When we think of the prominence of St. Michael in public worship before 1960, we can see when the worm began to enter the apple: with the reforms of Pope John XXIII.

Before 1960, St. Michael was invoked 7 times at Low Mass (9) and also at High Mass, (10) but two times less in both cases after 1960 with the suppression of the Confiteor before Communion.

A militant St. Michael in front of a church in Hamburg, Germany, dedicated to him

The Prayer to St. Michael – a prayer of Exorcism – mandated after every Low Mass as part of the Leonine Prayers (13) – was already under threat of extinction by 1960. It had been on the agenda of every international Liturgical Conference in the 1950s for elimination. (See here)

It is not surprising, therefore, that by 1962 there were rules already in place allowing the omission of the Leonine Prayers after Low Mass on a wide range of occasions, some examples being:

- When the Mass is preceded by a function e.g. distribution of ashes;

- When a homily is preached during the Mass;

- When the Mass is said in “dialogue” form on Sundays or Feast Days;

- When the Mass is followed by Benediction or a Novena. (14)

The final farewell to St. Michael

Five years later, when the Consilium produced the Novus Ordo Mass, St. Michael was written out of the text. Only on his feast day of September 29 is his name mentioned as an option in the Lectionary, but even this concession is withdrawn if his feast falls on a Sunday. Moreover, the Prince of the Heavenly Host, pre-eminent in the Angelic Hierarchy, now shares a group-title for his feast day with the other Archangels.

St. Michael, honored in the East and West for centuries

Who would have thought that a Pope would have inaugurated this campaign against St. Michael who, according to Tradition, is the Guardian Angel of each of the Sovereign Pontiffs? (15)

Pope John XXIII once stated,that “we must have a lively and profound devotion to our own Guardian Angel… and never forget him,” (16) but his enthusiasm for St. Michael seems to have flown out of the window he famously opened when “ecumenism” loomed on the horizon.

‘Ecumenism’ strikes again

The feast of the Apparition of St. Michael was a particularly sensitive issue because it stood at the intersection between private revelation and public liturgy. The very idea of angelic intervention – that St. Michael should appear in person, give instructions to individuals or intervene in human affairs – is dismissed by Protestants and progressist Catholics as mythology.

A depiction of the miracle at the cave where St. Michael indicated the place for the Sanctuary

Few Catholics nowadays have any awareness of the need to pray to St. Michael “to defend us in battle.” It is as if this strong, virile symbol of the Church Militant has been made redundant, having exchanged his sword for a white flag and adopted “dialogue” as a fig-leaf for surrender to the forces of evil.

St. Michael in the Sanctuary of Monte Gargano

Continued

- Paul the Deacon, Historia Langobardorum (History of the Lombards), translated by W. D. Foulke, New York, Longman, Green & Co., 1906, Chapter XLVI, p. 200. Paul the Deacon, himself of Lombard descent, was an 8th century scribe and historian in the court of Charlemagne.

- A bull, belonging to a man who lived on the mountain, having strayed from the herd, was found hemmed fast in the mouth of a cave. One of its pursuers shot an arrow with a view to rouse the animal by a wound; but the arrow rebounded and struck the one that had sent it.

This circumstance excited so much fear in the bystanders and in those who heard of it, that no one dared to go near the cave. The inhabitants of Siponto, therefore, consulted the Bishop; who answered that, in order to know God’s will, they must spend three days in fasting and prayer.

At the end of the three days, the Archangel Michael intimated to the Bishop that the place was under his protection, and that what had occurred was an indication of his will that God should be worshipped there, in honor of himself and the Angels. Whereupon, the Bishop repaired to the cave, together with his people. They found it like a church in shape, and began to use it for the celebration of the divine service. Many miracles were afterwards wrought there. - Interestingly, archaeological excavations at this cave have uncovered the ruins of a Christian place of worship dating from the late 5th century beneath a later sanctuary built in the 7th century by the Lombard Kings. (See Nicholas Everett, ‘The Liber de Apparitione S. Michaelis in Monte Gargano and the Hagiography of Dispossession,’ Analecta Bollandiana, vol. 120, Issue 2, 2002, p. 372)

- Martin Luther, Works, vol. 54, p. 247

- E.g. the influential Filipino liturgist, Anscar Chupungco O.S.B., stated: “The veneration of the bodies or relics of saints is a sad chapter in the history of the liturgy… When I was a student in Europe, it was one of my diversions to look for some of the most amusing kinds of relics: a feather of St. Michael the Archangel…” in his book What, Then, is Liturgy?: Musings and Memoir, Quezon City: Claretian Publications, 2010, p. 48.

- The earliest extant record of the event is the Liber de apparitione Sancti Michaelis in Monte Gargano (Book of the Apparition of St Michael on Monte Gargano), most likely written in the 7th century, which contains a reference to a lost 6th century account.

- The tradition of devotion to Saint Michael originated in the first century in Asia Minor near the city of Colossae (now in modern Turkey). In the 4th century, Constantine built in his honor a magnificent church, the Michaelion, near Constantinople.

- St Michael is, among other things, patron of the armed forces and the police.

- Twice in each of the 3 Confiteors and once in the Leonine Prayers after Mass.

- As above for the Confiteors, and once at the blessing of incense at the Offertory where the priest prays that “through the intercession of Blessed Michael the Archangel, standing at the right of the altar of incense, the Lord may deign to bless this incense, and receive it in an odor of sweetness.”

- Apocalypse 8: 3-4.

- “Relying upon the intercession of blessed Michael, Thine Archangel, O Lord, we Thy suppliants pray that what we perform with our lips we may attain with our hearts. Through Our Lord…”

- These prayers were first promulgated by Pope Leo XIII in 1884 (with St. Michael added in 1886) for use after Low Mass, but are not, strictly speaking, part of the Roman Missal.

- J. B. O’Connell, The Celebration of Mass, Milwaukee: Bruce Publishing Company, 1963, pp. 210-11. O’Connell references various decrees of the Sacred Congregation of Rites: SCR 3705, 3855, 3936, 3682, 3805.

- The frontispiece of the 1570 Missal depicts St. Pius V kneeling in pontifical regalia before the Archangel Michael. See Natalia Nowakowska, ‘From Strassburg to Trent: Bishops, Printing and Liturgical Reform in the Fifteenth Century’, Past & Present, vol. 213, Issue 1, November 2011, p. 27.

- Pope John XXIII, Meditation on the Guardian Angel, Discorsi, Messaggi, Colloqui del Santo Padre Giovanni XXIII, Libreria Editrice Vaticana, vol II: October 28, 1959- October 28, 1960, p. 762.

- It would be impossible to exaggerate the depth of the moral crisis in the Church after 50 years of Vatican II’s “softly-softly” approach to evil, i.e., Pope John’s “medicine of mercy.” Some Bishops, alarmed at the state of affairs but oblivious to their part in the crisis, have recommended the Prayer to St Michael after Mass. And Pope Francis conducted a shambolic ceremony in the Vatican Gardens on July 5, 2013, in which he dedicated the Vatican City State to the patronage of St Michael.

Nonetheless, the crisis continues to roar out of control under the leadership of a Pope who, according to authoritative voices in the Church, is actively stoking the fires that conti nue to produce the smoke of Satan famously mentioned by Paul VI.

Posted July 15, 2019

______________________

______________________

Volume I |

Volume II |

Volume III |

Volume IV |

Volume V |

Volume VI |

Volume VII |

Volume VIII |

Volume IX |

Volume X |

Volume XI |

Special Edition |