Traditionalist Issues

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Dialogue Mass - LXXIX

Ambiguous Language to Fool Conservatives

In the wake of Vatican II, traditional choirmasters and organists ‒ many of whom were of professional status ‒ wishing to preserve the Church’s treasury of sacred music, were astonished to find that their services were no longer required, and that their field of expertise was flooded by guitar groups and congregational singing.

They immediately found themselves with the impossible task of trying to balance the musical heritage of the Church with the demands of the Novus Ordo liturgy.

They immediately found themselves with the impossible task of trying to balance the musical heritage of the Church with the demands of the Novus Ordo liturgy.

The clear message of the reformers was that congregational singing should take precedence over sacred chant sung by the choir, as Mgr. Frederick McManus explained as early as 1956:

“The trained choir may lead and encourage the people ‒ and above all, never seek to restrict the participation of the faithful. If on occasion this means that the responses, for example, may not be sung perfectly, the act of worship on the part of the assembled people will nevertheless be pleasing to almighty God. And the strong and united worship of the whole Church must never be subordinated to technical perfection of music.” (1)

As a result, respect for the magnificent achievements of choirs in masterworks of skill and beauty was lost in the indiscriminate desire to drag standards down to within reach of the people.

Blaming the victim

Archbishop Bugnini stated that “the people must truly sing in order to participate actively as desired by the liturgical Constitution,” and denounced conservatives who believed that participation could be achieved by listening to the choir. He airily dismissed their earnest concerns with the insult that they “betrayed a mentality that could not come to grips with new pastoral needs.” (2)

As the musicians had little or no leverage in the matter, they largely withdrew from the fray. In his Memoirs, Bugnini describes the 10-year battle royal he conducted against the conservative musicians, (3) from which he emerged victorious. Like a latter day Goliath, and leader of the (liturgical) philistines, Bugnini may have won this battle, (4) but not the war, which is still being fought by traditionalists as a counter-revolution to regain the Church’s full liturgical and spiritual patrimony.

How conservative expectations were violated

The conciliar Liturgy Constitution Sacrosanctum Concilium was a document that apparently championed the tradition of Gregorian Chant and the Latin language but which, when examined more closely, contained a number of escape clauses which rendered that tradition inert.

Conservatives are fond of quoting §36.1: “The use of the Latin language is to be preserved in the Latin rites,” and demand that the Constitution be obeyed. But, by focusing only on the “positives” of the article, they overlook, or perhaps fail to understand, the caveat in the same sentence:

salvo particulari iure (without prejudice to particular law), which came to mean if not prohibited by the diocesan Bishops. (5)

Conservatives are fond of quoting §36.1: “The use of the Latin language is to be preserved in the Latin rites,” and demand that the Constitution be obeyed. But, by focusing only on the “positives” of the article, they overlook, or perhaps fail to understand, the caveat in the same sentence:

salvo particulari iure (without prejudice to particular law), which came to mean if not prohibited by the diocesan Bishops. (5)

Most of the Council Fathers had no idea in 1963 of the new doctrine of “collegiality” being planned or of the imminent rise of the National Episcopal Conferences which would be granted unprecedented power over the liturgy. (6) They made the fatal mistake of assuming that the Council was in continuity with Tradition. It was an assumption that was rapidly to be confounded.

Bugnini later explained the real intention behind §36.1 (which was mostly unknown to the Council Fathers when they voted):

“When, therefore, the Constitution allowed the introduction of the vernaculars, it necessarily anticipated that the preservation of this “treasure of sacred music” would be dependent solely on celebrations in Latin.” (7)

The significance here is that the deception is based on exploitation of the victims’ assumptions. Everyone assumed that “Latin rites” in §36.1 meant Western rites. But, while Bugnini’s explanation was factually correct, it was part of his stock-in-trade of rhetorical tactics and ploys, a subtle shifting of focus with intent to deceive.

No one suspected that he was making a tautological statement that Latin is to be used in rites celebrated in Latin, or that he was being dishonest while telling the truth. In other words he spoke a truth, but not the one he knew the conservative voters expected.

A progressivist victory

Let us now look at other paragraphs in the Liturgy Constitution that deceive the reader into thinking that a statement is more conservative than it really is. This was achieved by the rhetorical device known as “paltering” – the use of truthful information to give a misleading impression.

The Constitution specified that Gregorian Chant “should be given pride of place”; but the point about it is that, instead of safeguarding that mandate, it betrayed it in the same sentence with the qualifier “ceteris paribus” (other things being equal). The unequal factors overriding this stipulation were, as always, “active participation,” the vernacular and adaptation to contemporary cultures.

Two years after the closing of the Council, the Instruction Musicam Sacram (1967), the work of the Consilium to implement the Liturgy Constitution, openly revealed that the “pride of place” clause relating to Gregorian Chant applied only to “sung liturgical services celebrated in Latin.” (§50)

This applies also to the Constitution’s grudging concession that Polyphony is “not excluded.” (§116) However, the reformers made sure that it would have little or no place in the new liturgy which, as events would prove, was unsuited to accommodate in either the spirit or the logistics of the Novus Ordo Mass.

‘What all can’t sing, no one shall sing’

Besides, in what looked like an act of ideological spite, Musicam Sacram, clarifying the Constitution, deprecated and officially cast out of the liturgy the tradition of the exclusive rendering of the Mass Ordinary and Proper by the choir, (8) on the grounds that the people could not join in everything.

So, the “pride of place” reputedly allotted to Gregorian Chant was, in reality, intended all along for the congregation, whose preferential treatment over the choir led to the marginalization and demise of polyphony.

So, the “pride of place” reputedly allotted to Gregorian Chant was, in reality, intended all along for the congregation, whose preferential treatment over the choir led to the marginalization and demise of polyphony.

Another escape clause in the Constitution was pro opportunitate (§115), meaning when it is (judged) appropriate, which in practice means that something is merely optional and may be omitted. This expression is often found in the new liturgical books. It was intended to give a certain liberty and flexibility to the rubrics. When taken to its logical conclusion, it allowed for the exclusion of certain traditions such as Gregorian Chant, incense, bells etc.

The gloves are off

As soon as the reformers felt their victory secure, they cast aside all pretence of preserving the Church’s musical heritage.

In 1987, the Congregation for Divine Worship stated:

“Any performance of sacred music which takes place during a celebration should be fully in harmony with that celebration. This often means that musical compositions which date from a period when the active participation of the faithful was not emphasized as the source of the authentic Christian spirit (SC n. 14; Pius X Tra le sollecitudini) are no longer to be considered suitable for inclusion within liturgical celebrations.” (9)

Apart from the absurdity of using Pius X for the destruction of what he held most dear, (10) the virtual disappearance of Chant and Polyphony – deliberately engineered by the reformers themselves – was then used as an argument to justify banishing them from the liturgy.

Apart from the absurdity of using Pius X for the destruction of what he held most dear, (10) the virtual disappearance of Chant and Polyphony – deliberately engineered by the reformers themselves – was then used as an argument to justify banishing them from the liturgy.

What, then, became of the Constitution’s statement that the “treasury of sacred music is to be preserved and cultivated with great care”? (§114) Two years later, it was relegated to “concert programmes both inside and outside of church,” a decision “deemed necessary in the pursuit of an end of greater importance, namely the active participation of the faithful.” (11)

There could hardly have been a clearer admission of the man-made, man-centred nature of the Novus Ordo liturgy. This shows that the basic struggle underlying the reform was a moral and spiritual one, that is, whether the liturgy exists for the self-expression of the people or, as Pius X taught, primarily for the glorification of God. The essence of the conflict, therefore, was not simply a matter of musical style and personal taste, but about the correct perception of God and how we should worship Him in the liturgy.

The Constitution praised the Church’s musical heritage as “a treasure of inestimable value” (§112), while permitting it to be turned into its own negation. Such hypocrisy makes a mockery of Tradition and is reminiscent of the adage by the Roman satirist, Juvenal: “Virtue is praised then left in the cold.” (12)

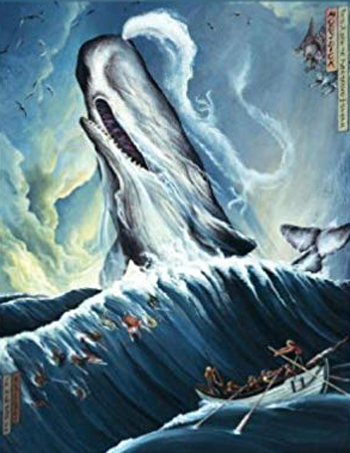

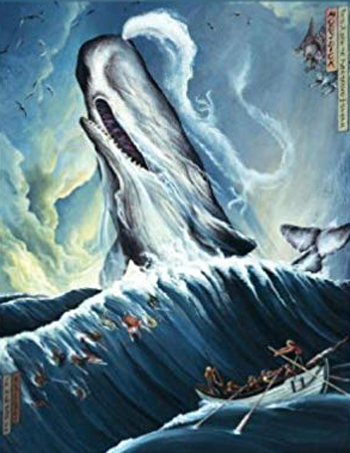

Time to stop chasing the white whale (13)

Even among the more conservative Catholics, there are still some who suffer from what might be termed the “Moby Dick syndrome.” They insist on chasing the ever-elusive “correct” form of “active participation.”

But it is a self-defeating exercise: “active participation” was never anything more than a subterfuge to undermine the ministerial priesthood. Why should any Catholic worthy of the name support the fanatical mission of the Liturgical Establishment to destroy its own spiritual heritage?

But it is a self-defeating exercise: “active participation” was never anything more than a subterfuge to undermine the ministerial priesthood. Why should any Catholic worthy of the name support the fanatical mission of the Liturgical Establishment to destroy its own spiritual heritage?

They fail to grasp that “active participation” has become the law that subverts the law (of prayer). It is a problem inherent in the liturgical reform since the time of Pius XII.

What they do not realize is that their efforts to restore the fullness of Tradition are always going to be thwarted by the Liturgical Establishment which would never allow them fully to defend the Church’s musical heritage.

So, they are left with the choice of either compromising traditional values or bending the Novus Ordo rules to accommodate some forbidden traditional practices.

In such a hostile environment, they may achieve some limited measure of success only to find that, somewhere along the line, Bugnini’s ghost has come back to haunt them.

Continued

'Divine Worship' songbooks promote congregational singing

The clear message of the reformers was that congregational singing should take precedence over sacred chant sung by the choir, as Mgr. Frederick McManus explained as early as 1956:

“The trained choir may lead and encourage the people ‒ and above all, never seek to restrict the participation of the faithful. If on occasion this means that the responses, for example, may not be sung perfectly, the act of worship on the part of the assembled people will nevertheless be pleasing to almighty God. And the strong and united worship of the whole Church must never be subordinated to technical perfection of music.” (1)

As a result, respect for the magnificent achievements of choirs in masterworks of skill and beauty was lost in the indiscriminate desire to drag standards down to within reach of the people.

Blaming the victim

Archbishop Bugnini stated that “the people must truly sing in order to participate actively as desired by the liturgical Constitution,” and denounced conservatives who believed that participation could be achieved by listening to the choir. He airily dismissed their earnest concerns with the insult that they “betrayed a mentality that could not come to grips with new pastoral needs.” (2)

As the musicians had little or no leverage in the matter, they largely withdrew from the fray. In his Memoirs, Bugnini describes the 10-year battle royal he conducted against the conservative musicians, (3) from which he emerged victorious. Like a latter day Goliath, and leader of the (liturgical) philistines, Bugnini may have won this battle, (4) but not the war, which is still being fought by traditionalists as a counter-revolution to regain the Church’s full liturgical and spiritual patrimony.

How conservative expectations were violated

The conciliar Liturgy Constitution Sacrosanctum Concilium was a document that apparently championed the tradition of Gregorian Chant and the Latin language but which, when examined more closely, contained a number of escape clauses which rendered that tradition inert.

Today, singing at St. Mark's Catholic Church, above, appears no different from a Baptist service, below

Most of the Council Fathers had no idea in 1963 of the new doctrine of “collegiality” being planned or of the imminent rise of the National Episcopal Conferences which would be granted unprecedented power over the liturgy. (6) They made the fatal mistake of assuming that the Council was in continuity with Tradition. It was an assumption that was rapidly to be confounded.

Bugnini later explained the real intention behind §36.1 (which was mostly unknown to the Council Fathers when they voted):

“When, therefore, the Constitution allowed the introduction of the vernaculars, it necessarily anticipated that the preservation of this “treasure of sacred music” would be dependent solely on celebrations in Latin.” (7)

The significance here is that the deception is based on exploitation of the victims’ assumptions. Everyone assumed that “Latin rites” in §36.1 meant Western rites. But, while Bugnini’s explanation was factually correct, it was part of his stock-in-trade of rhetorical tactics and ploys, a subtle shifting of focus with intent to deceive.

No one suspected that he was making a tautological statement that Latin is to be used in rites celebrated in Latin, or that he was being dishonest while telling the truth. In other words he spoke a truth, but not the one he knew the conservative voters expected.

A progressivist victory

Let us now look at other paragraphs in the Liturgy Constitution that deceive the reader into thinking that a statement is more conservative than it really is. This was achieved by the rhetorical device known as “paltering” – the use of truthful information to give a misleading impression.

The Constitution specified that Gregorian Chant “should be given pride of place”; but the point about it is that, instead of safeguarding that mandate, it betrayed it in the same sentence with the qualifier “ceteris paribus” (other things being equal). The unequal factors overriding this stipulation were, as always, “active participation,” the vernacular and adaptation to contemporary cultures.

Two years after the closing of the Council, the Instruction Musicam Sacram (1967), the work of the Consilium to implement the Liturgy Constitution, openly revealed that the “pride of place” clause relating to Gregorian Chant applied only to “sung liturgical services celebrated in Latin.” (§50)

This applies also to the Constitution’s grudging concession that Polyphony is “not excluded.” (§116) However, the reformers made sure that it would have little or no place in the new liturgy which, as events would prove, was unsuited to accommodate in either the spirit or the logistics of the Novus Ordo Mass.

‘What all can’t sing, no one shall sing’

Besides, in what looked like an act of ideological spite, Musicam Sacram, clarifying the Constitution, deprecated and officially cast out of the liturgy the tradition of the exclusive rendering of the Mass Ordinary and Proper by the choir, (8) on the grounds that the people could not join in everything.

Ambiguous language led to the end of trained choirs of clerics and men

Another escape clause in the Constitution was pro opportunitate (§115), meaning when it is (judged) appropriate, which in practice means that something is merely optional and may be omitted. This expression is often found in the new liturgical books. It was intended to give a certain liberty and flexibility to the rubrics. When taken to its logical conclusion, it allowed for the exclusion of certain traditions such as Gregorian Chant, incense, bells etc.

The gloves are off

As soon as the reformers felt their victory secure, they cast aside all pretence of preserving the Church’s musical heritage.

In 1987, the Congregation for Divine Worship stated:

“Any performance of sacred music which takes place during a celebration should be fully in harmony with that celebration. This often means that musical compositions which date from a period when the active participation of the faithful was not emphasized as the source of the authentic Christian spirit (SC n. 14; Pius X Tra le sollecitudini) are no longer to be considered suitable for inclusion within liturgical celebrations.” (9)

Website banner falsely proclaiming that St. Pius X was a Vatican II liturgical precursor

What, then, became of the Constitution’s statement that the “treasury of sacred music is to be preserved and cultivated with great care”? (§114) Two years later, it was relegated to “concert programmes both inside and outside of church,” a decision “deemed necessary in the pursuit of an end of greater importance, namely the active participation of the faithful.” (11)

There could hardly have been a clearer admission of the man-made, man-centred nature of the Novus Ordo liturgy. This shows that the basic struggle underlying the reform was a moral and spiritual one, that is, whether the liturgy exists for the self-expression of the people or, as Pius X taught, primarily for the glorification of God. The essence of the conflict, therefore, was not simply a matter of musical style and personal taste, but about the correct perception of God and how we should worship Him in the liturgy.

The Constitution praised the Church’s musical heritage as “a treasure of inestimable value” (§112), while permitting it to be turned into its own negation. Such hypocrisy makes a mockery of Tradition and is reminiscent of the adage by the Roman satirist, Juvenal: “Virtue is praised then left in the cold.” (12)

Time to stop chasing the white whale (13)

Even among the more conservative Catholics, there are still some who suffer from what might be termed the “Moby Dick syndrome.” They insist on chasing the ever-elusive “correct” form of “active participation.”

Chasing Moby Dick and taking down the others in the boat as well...

They fail to grasp that “active participation” has become the law that subverts the law (of prayer). It is a problem inherent in the liturgical reform since the time of Pius XII.

What they do not realize is that their efforts to restore the fullness of Tradition are always going to be thwarted by the Liturgical Establishment which would never allow them fully to defend the Church’s musical heritage.

So, they are left with the choice of either compromising traditional values or bending the Novus Ordo rules to accommodate some forbidden traditional practices.

In such a hostile environment, they may achieve some limited measure of success only to find that, somewhere along the line, Bugnini’s ghost has come back to haunt them.

Continued

- Frederick McManus, The Rites of Holy Week: Ceremonies, Preparation, Music, Commentaries, Paterson, NJ: St. Anthony Guild Press, , 1956, pp. 33-34.

- Annibale Bugnini, The Reform of the Liturgy 1948-1975, trans. Matthew J. O'Connell, Collegeville, MN: The Liturgical Press, 1990, p. 904

- Ibid., p. 907

- A parallel to the situation of Bugnini and the traditionalists can be seen in Thermopylae (480 B.C.), one of the most famous battles in European ancient history. It was conducted by the Spartan King Leonidas against the Persian invaders under Xerxes who had set out to conquer all of Greece. Although the Persians won that particular battle, the Greeks achieved a moral victory through their courageous resistance.

Leonidas went down in history as the hero who fought to the death with little assistance against vastly superior numbers, a tactic that allowed most of his army to retreat and avoid certain doom. The survivors regrouped and fought again at Salamis and at Plataea, where the Persian forces were destroyed. Thus, the self-sacrifice of Leonidas saved Europe from invasion by Asia for hundreds of years.

Both ancient and modern writers have used the Battle of Thermopylae as a symbol of courage, illustrating the patriotism of the contingent which defended its native soil in the face of overwhelming odds – surely a metaphor for traditionalists in their struggle to defend their spiritual patrimony. - In the new Vatican II structures of collegiality, particular laws are made by the Conference of Bishops at the national level, virtually always rubber-stamped by the Holy See, and imposed on the faithful of each country.

- §22.2 grants an unprecedented degree of control over the liturgy to “various kinds of competent territorial bodies of bishops.”

- A. Bugnini, The Reform of the Liturgy 1948-1975, p. 907.

- Musicam Sacram (§16c): “the usage of entrusting to the choir alone the entire singing of the whole Proper and of the whole Ordinary, to the complete exclusion of the people’s participation in the singing, is to be deprecated.”

- Congregation for Divine Worship, Concerts in Churches, November 5, 1987, § 6.

- As a seminarian, young chaplain, Bishop, Cardinal, Patriarch and Pope, Pius X devoted every stage of his life to promoting Gregorian Chant. In 1911, he founded the Pontifical Institute of Sacred Music in Rome for the study and practice of Gregorian Chant and Polyphony to ensure their use for future generations..

- Musicam Sacram (§2)

- “Probitas laudatur et alget“ – Virtue is praised then left in the cold – Juvenal, Satires, I, line 74.

- In Herman Melville’s novel, Moby Dick, Captain Ahab’s fanatical and ill-fated quest to destroy the great white whale led to his own destruction and that of all of his crew members except one – they were dragged down into Davy Jones’ Locker (a nautical idiom for the bottom of the sea).

Posted November 23, 2018

______________________

______________________

Volume I |

Volume II |

Volume III |

Volume IV |

Volume V |

Volume VI |

Volume VII |

Volume VIII |

Volume IX |

Volume X |

Volume XI |

Special Edition |