Traditionalist Issues

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Dialogue Mass - LXXXIII

How the 1962 Missal Acquired

Its Calendar Reform

Historical evidence shows that the changes made by Pope John XXIII to the General Roman Calendar in 1960 (1) were a continuation and extension of the work of the Commission set up by Pius XII. The schema for the reform of the Calendar had already been drawn up in 1951 by two of its members: Fr. Löw under the supervision of Fr. Antonelli. (2)

At the instigation of Fr. Bea (also a member of Pius XII’s Commission), the same schema was forwarded to the members and consultors of Vatican II’s Preparatory Commission on the Liturgy (3) – to which John XXIII appointed Fr. Bugnini as its Secretary in 1960.

At the instigation of Fr. Bea (also a member of Pius XII’s Commission), the same schema was forwarded to the members and consultors of Vatican II’s Preparatory Commission on the Liturgy (3) – to which John XXIII appointed Fr. Bugnini as its Secretary in 1960.

We can conclude, therefore, that Bugnini was placed in this influential position specifically to co-ordinate the team work in the revolutionary cause of restructuring the Roman liturgy. Moreover, he was hailed as the guiding spirit who organized the Preparatory Liturgical Commission’s agenda and steered it in a progressivist direction. (4)

As most of the 1960 Commission members were in varying degrees supporters of liturgical revolution – some, indeed, were formidable adversaries of Tradition (5) – this Calendar reform bears the hallmarks of manipulation by a group of “interested parties” who were in the process of achieving their long-term goal of destroying the Church’s ancient traditions.

Space does not allow a full treatment of the details and scope of the 1960 Calendar reform, which was incorporated into the 1962 Missal. We will here consider only its most salient feature – the elimination of selected feast days from the Liturgical Year.

To try to establish a balance, with due proportionality, between the Temporal Cycle (feasts of Our Lord, Sundays and Ferias) and the Sanctoral Cycle (the Proper of the Saints) is one thing; John XXIII’s reform, however, is quite another. It was but the latest manifestation of the reformers’ belief in what they called “simplification” of the Roman Rite, but which might more appropriately be termed “liturgical cleansing” of those elements of the Rite of which they personally disapproved.

Here is our first example.

Abolition of the Chair of St. Peter feast at Rome

From the 4th century until 1960, the feast of the Chair of St. Peter was celebrated twice yearly, under different titles – the Chair of St. Peter at Rome (18 January) (6) and the Chair of St. Peter at Antioch (22 February). The two Feasts were included in the Tridentine Calendar, though they both preceded the Council of Trent by many centuries.

In this way, the Church acknowledged in her liturgy the importance of the seat of the Petrine Ministry – symbolized by a Chair – in both of these geographic locations where St. Peter served as Bishop. But as the January 18 feast of the Chair of St. Peter is that of the foundation of the See of Rome, it gives fitting liturgical testimony to the primacy of honor and jurisdiction attached to the Bishop of Rome.

In this way, the Church acknowledged in her liturgy the importance of the seat of the Petrine Ministry – symbolized by a Chair – in both of these geographic locations where St. Peter served as Bishop. But as the January 18 feast of the Chair of St. Peter is that of the foundation of the See of Rome, it gives fitting liturgical testimony to the primacy of honor and jurisdiction attached to the Bishop of Rome.

In 1960, however, Pope John XXIII abolished it. As for its counterpart in February, the feast was saved, but its title was altered to exclude any reference to Antioch: it was renamed the “Chair of Saint Peter Apostle.”

Neither Rome nor Antioch

Not only has the 1962 Missal a gaping hole where a feast of major importance should be, but the reformed Calendar lacks any marker indicating where the center of the Church and its teaching authority were historically seated. As a result, the See of Peter, i.e., the seat of government of the universal Church, appears somewhat surreal, an abstract idea disconnected from any geographical location. Henceforth, the Chair could be made to say or do anything the “puppeteer” Popes wanted.

As Christ the King must have dominion over the Church and the world, Providence has disposed that He should not only have His Vicar on earth to rule in His Name, but also a tangible, material throne located in Rome. A relic, traditionally held to be the actual Chair from which St. Peter taught in Rome, is preserved in a sumptuous monument, the imposing bronze reliquary of Bernini, over the altar in the apse of St. Peter’s Basilica.

An ecumenically sensitive issue

Few issues in the History of the Church have been more acrimoniously challenged by heretics and schismatics than the primacy of Peter and the See of Rome. As the Church had established this feast day to celebrate the universal jurisdiction of the Bishop of Rome, particularly his magisterial authority in proclaiming doctrine ex cathedra, i.e., with infallibility, it was an obvious source of embarrassment for those promoting “ecumenism.”

During the Council of Trent, Pope Paul IV extended the feast of the Chair of St. Peter at Rome to the universal Church, (7) in response to the 16th century Protestant reformers’ rejection of the primacy of the Roman Pontiff. In fact, they even denied that St. Peter was ever in Rome – because it did not say so in the Bible – or that he had any successors as Bishop of Rome, in spite of the incontestable evidence from historical sources.

Here we touch on the real reason why the feast had to be abolished and any mention of Rome expunged from the title. As Fr. Hans Küng remarked:

“If Catholic worship is successfully refashioned in a more ecumenical form, the effect on the whole movement towards reunion with separated Christians will be decisive.” (8)

The primacy of Ecumenism

Given that the January 18 feast was abolished so as not to offend the Protestants, Küng’s predictions were fulfilled in the most blatantly sacrilegious manner – impossible for most Catholics even to imagine in 1960.

In March 2017, an Anglican service of Evensong, based on Cranmer’s 1662 Book of Common Prayer,

was celebrated at the altar of the Chair of St. Peter in Rome, with the participation of Archbishop Arthur Roche, Secretary of the Congregation for Divine Worship and the Discipline of the Sacraments. (9)

In March 2017, an Anglican service of Evensong, based on Cranmer’s 1662 Book of Common Prayer,

was celebrated at the altar of the Chair of St. Peter in Rome, with the participation of Archbishop Arthur Roche, Secretary of the Congregation for Divine Worship and the Discipline of the Sacraments. (9)

Let us not be persuaded that the abolition of the Chair of St. Peter at Rome was undertaken for the sake of “simplification” of the Calendar. Pope John XXIII’s suppression of the feast and Archbishop Roche’s liturgical sharing with Anglicans were conducted in the same “ecumenical” spirit. The former was a clear repudiation of Paul IV’s efforts to defend the Papacy from Protestant attacks during the Reformation; and the latter, a communicatio in sacris, (10) was an indefensible desecration of a Catholic altar dedicated to the first Pope.

The absurdity of these ecumenical gestures of “unity” when they involve Anglicans lies in the fact that the very reason the Church of England was established in the first place was for the purpose of resisting the universal jurisdiction of the Pope, represented by the Chair of St Peter in Rome. (11)

In 1967, in a speech that evinced no gratitude whatsoever for the gift of the Papacy from Christ to St. Peter and his Successors, Paul VI denigrated the Papacy as an obstacle to be cast aside, as if Our Lord had given a defective gift to His Bride, the Church:

“The Pope, as we well know, is undoubtedly the greatest obstacle on the road to unity.” (12)

It is obvious that he was not alluding to that perpetual Catholic unity symbolized in the Chair of St. Peter in Rome and fully honored in the Tridentine Missal. His words were eagerly construed by progressivists as a signal to re-found and refashion the Petrine Primacy for the sake of “ecumenism.” (13)

The Papacy trampled underfoot by Vatican II Popes

As for the traditional Papacy, it was kicked into the long grass to be ignored or forgotten. Since Vatican II, it has undergone a profound “collegial” makeover, whereby the Popes themselves have gradually surrendered their powers of government to Episcopal Conferences. No wonder the Papal Primacy over the whole Church has become weak and almost paralyzed.

John XXIII’s “ecumenical” reform can be seen as the curtain-raiser to this main full-length tragedy. What a contrast with the Papacy of Pope St. Leo the Great (440-461), which was one continuous, unrelenting defense of the Chair of St. Peter in Rome as the divinely appointed guarantee that the truth of the Gospels is faithfully transmitted down the centuries. (14)

The omission of this feast constitutes a loss to the Church’s lex orandi and weakens the liturgical expression of a central doctrine of the Catholic Faith. It may please Protestants and progressivists, but it dampens the traditional Catholic veneration for the Roman See generated by the former feast day.

To quote Dom Guéranger:

“The children of the Church have a right to feel a special interest in every solemnity that is kept in memory of St. Peter”. (15) This, of course, includes the feast of the Chair of St. Peter in Rome, but those who follow the 1962 Missal are unlikely even to know of its existence.

Continued

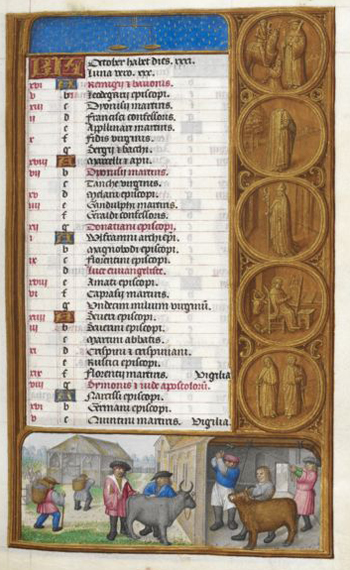

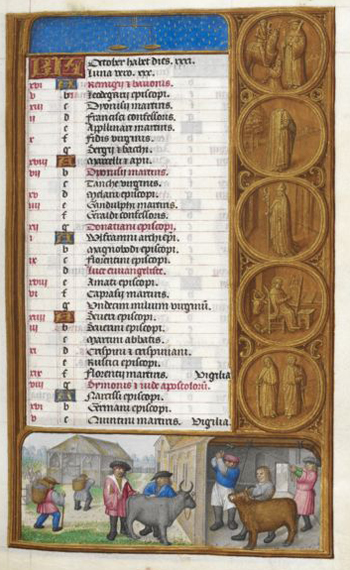

Calendar of Saints - October, 15th c.

We can conclude, therefore, that Bugnini was placed in this influential position specifically to co-ordinate the team work in the revolutionary cause of restructuring the Roman liturgy. Moreover, he was hailed as the guiding spirit who organized the Preparatory Liturgical Commission’s agenda and steered it in a progressivist direction. (4)

As most of the 1960 Commission members were in varying degrees supporters of liturgical revolution – some, indeed, were formidable adversaries of Tradition (5) – this Calendar reform bears the hallmarks of manipulation by a group of “interested parties” who were in the process of achieving their long-term goal of destroying the Church’s ancient traditions.

Space does not allow a full treatment of the details and scope of the 1960 Calendar reform, which was incorporated into the 1962 Missal. We will here consider only its most salient feature – the elimination of selected feast days from the Liturgical Year.

To try to establish a balance, with due proportionality, between the Temporal Cycle (feasts of Our Lord, Sundays and Ferias) and the Sanctoral Cycle (the Proper of the Saints) is one thing; John XXIII’s reform, however, is quite another. It was but the latest manifestation of the reformers’ belief in what they called “simplification” of the Roman Rite, but which might more appropriately be termed “liturgical cleansing” of those elements of the Rite of which they personally disapproved.

Here is our first example.

Abolition of the Chair of St. Peter feast at Rome

From the 4th century until 1960, the feast of the Chair of St. Peter was celebrated twice yearly, under different titles – the Chair of St. Peter at Rome (18 January) (6) and the Chair of St. Peter at Antioch (22 February). The two Feasts were included in the Tridentine Calendar, though they both preceded the Council of Trent by many centuries.

At the altar dedicated to the Cathedra of Peter in St. Peter's Basilica, an Anglican service was led by Protestant archbishop David Moxon, center, with the participation of the Vatican's Archbishop Roche, left, using the Book of Common Prayer

In 1960, however, Pope John XXIII abolished it. As for its counterpart in February, the feast was saved, but its title was altered to exclude any reference to Antioch: it was renamed the “Chair of Saint Peter Apostle.”

Neither Rome nor Antioch

Not only has the 1962 Missal a gaping hole where a feast of major importance should be, but the reformed Calendar lacks any marker indicating where the center of the Church and its teaching authority were historically seated. As a result, the See of Peter, i.e., the seat of government of the universal Church, appears somewhat surreal, an abstract idea disconnected from any geographical location. Henceforth, the Chair could be made to say or do anything the “puppeteer” Popes wanted.

As Christ the King must have dominion over the Church and the world, Providence has disposed that He should not only have His Vicar on earth to rule in His Name, but also a tangible, material throne located in Rome. A relic, traditionally held to be the actual Chair from which St. Peter taught in Rome, is preserved in a sumptuous monument, the imposing bronze reliquary of Bernini, over the altar in the apse of St. Peter’s Basilica.

An ecumenically sensitive issue

Few issues in the History of the Church have been more acrimoniously challenged by heretics and schismatics than the primacy of Peter and the See of Rome. As the Church had established this feast day to celebrate the universal jurisdiction of the Bishop of Rome, particularly his magisterial authority in proclaiming doctrine ex cathedra, i.e., with infallibility, it was an obvious source of embarrassment for those promoting “ecumenism.”

During the Council of Trent, Pope Paul IV extended the feast of the Chair of St. Peter at Rome to the universal Church, (7) in response to the 16th century Protestant reformers’ rejection of the primacy of the Roman Pontiff. In fact, they even denied that St. Peter was ever in Rome – because it did not say so in the Bible – or that he had any successors as Bishop of Rome, in spite of the incontestable evidence from historical sources.

Here we touch on the real reason why the feast had to be abolished and any mention of Rome expunged from the title. As Fr. Hans Küng remarked:

“If Catholic worship is successfully refashioned in a more ecumenical form, the effect on the whole movement towards reunion with separated Christians will be decisive.” (8)

The primacy of Ecumenism

Given that the January 18 feast was abolished so as not to offend the Protestants, Küng’s predictions were fulfilled in the most blatantly sacrilegious manner – impossible for most Catholics even to imagine in 1960.

A milestone of ecumenism: Anglican Evensong sung at the Altar of St. Peter in the Vatican, March 2017

Let us not be persuaded that the abolition of the Chair of St. Peter at Rome was undertaken for the sake of “simplification” of the Calendar. Pope John XXIII’s suppression of the feast and Archbishop Roche’s liturgical sharing with Anglicans were conducted in the same “ecumenical” spirit. The former was a clear repudiation of Paul IV’s efforts to defend the Papacy from Protestant attacks during the Reformation; and the latter, a communicatio in sacris, (10) was an indefensible desecration of a Catholic altar dedicated to the first Pope.

The absurdity of these ecumenical gestures of “unity” when they involve Anglicans lies in the fact that the very reason the Church of England was established in the first place was for the purpose of resisting the universal jurisdiction of the Pope, represented by the Chair of St Peter in Rome. (11)

In 1967, in a speech that evinced no gratitude whatsoever for the gift of the Papacy from Christ to St. Peter and his Successors, Paul VI denigrated the Papacy as an obstacle to be cast aside, as if Our Lord had given a defective gift to His Bride, the Church:

“The Pope, as we well know, is undoubtedly the greatest obstacle on the road to unity.” (12)

It is obvious that he was not alluding to that perpetual Catholic unity symbolized in the Chair of St. Peter in Rome and fully honored in the Tridentine Missal. His words were eagerly construed by progressivists as a signal to re-found and refashion the Petrine Primacy for the sake of “ecumenism.” (13)

The Papacy trampled underfoot by Vatican II Popes

As for the traditional Papacy, it was kicked into the long grass to be ignored or forgotten. Since Vatican II, it has undergone a profound “collegial” makeover, whereby the Popes themselves have gradually surrendered their powers of government to Episcopal Conferences. No wonder the Papal Primacy over the whole Church has become weak and almost paralyzed.

John XXIII’s “ecumenical” reform can be seen as the curtain-raiser to this main full-length tragedy. What a contrast with the Papacy of Pope St. Leo the Great (440-461), which was one continuous, unrelenting defense of the Chair of St. Peter in Rome as the divinely appointed guarantee that the truth of the Gospels is faithfully transmitted down the centuries. (14)

The omission of this feast constitutes a loss to the Church’s lex orandi and weakens the liturgical expression of a central doctrine of the Catholic Faith. It may please Protestants and progressivists, but it dampens the traditional Catholic veneration for the Roman See generated by the former feast day.

To quote Dom Guéranger:

“The children of the Church have a right to feel a special interest in every solemnity that is kept in memory of St. Peter”. (15) This, of course, includes the feast of the Chair of St. Peter in Rome, but those who follow the 1962 Missal are unlikely even to know of its existence.

Continued

- These changes were mandated on July 23, 1960, by John XXIII in his motu proprio Rubricarum instructum, and were incorporated into the 1962 Missal.

- Sacred Congregation of Rites, Memoria Sulla Riforma Liturgica: Supplemento III - Materiale Storico, Agiografico, Liturgico per la Riforma del Calendario, published in 1951 for private circulation among Commission members and selected reformers.

- Bugnini confirmed that the schema of the Preparatory Commission was, with few modifications, basically the same as the Liturgy Constitution passed by the Council Fathers in 1963 (A. Bugnini, Notitiae, n. 70, February 1972, pp. 33-34).

- The Dominican Fr. Pierre-Marie Gy, one of the consultors to the Preparatory Commission on the Liturgy, described Bugnini as “a happy choice as Secretary” on the grounds that “he had been Secretary of the Commission for reform set up by Pius XII. He was a gifted organizer and possessed an open-minded, pastoral spirit. Many people noted how, with Cardinal Cicognani, he was able to imbue the discussion with the liberty of spirit recommended by Pope John XXIII” (Apud A. Flannery, Vatican II: The Liturgy Constitution, Dublin: Sceptre Books, 1964, p. 20). Emphasis added.

- Most of the members were well-known activists in the Liturgical Movement: Frs. Romano Guardini, Aimon-Marie Roguet, Bernard Capelle, Josef Jungmann and Mario Righetti (the last three having served as consultors of Pius XII’s Liturgical Commission); the consultors of the 1960 Commission were also prominent reformers including: Frs. Frederick McManus, Bernard Botte, Godfrey Diekmann, Pierre-Marie Gy, Johannes Hofinger (a disciple of Josef Jungmann), Pierre Jounel, Aimé-Georges Martimort, Cipriano Vagaggini, Balthasar Fischer and Johannes Wagner, founder and director of the Liturgical Institute of Trier, Germany, in 1947.

- This was the date given in the ancient manuscripts, particularly the “Martyrology of St. Jerome.”

- In the Bull, Ineffabilis Divinae Providentiae (1558): “Non solum in hac Alma Urbe, verum etiam in universis orbis ecclesiis” (not only in this City of Rome, but also in all the churches of the world).

- Hans Küng, The Council and Reunion, London, Sheed and Ward, 1963, p. 197.

- The Catholic Herald, March 14, 2017. This was not a case of Protestants simply being present at a Catholic liturgy. The shared liturgy took place at the altar, and was presided over by David Moxon, the Archbishop of Canterbury’s representative and Director of the Anglican Centre in Rome, with the active participation of Archbishop Roche.

- The Church has always taught that actively joining in non-Catholic religious services is a violation of Divine Law. The mere act of sharing the worship of a non-Catholic group, irrespective of one’s inner beliefs, implies a common creed with that group and, hence, constitutes a sin against the Catholic Faith. This explains why, as Pius XI taught in the 1928 Encyclical Mortalium animos that “the Apostolic See cannot on any terms take part in their assemblies.” It is not surprising that this Encyclical is not mentioned, either directly or indirectly, in Vatican II’s document on Ecumenism, Unitatis redintegratio. Nor is there a single reference to it in the so-called Catechism of the Catholic Church, which diverges fundamentally from the Catholic doctrine on this issue.

- The Church of England was established by Henry VIII with his Act of Supremacy (1534). This Act made the King supreme head of the so-called Church in England, and made allegiance to the Pope an act of treason against the Monarchy. A year later, St. John Fisher, Bishop of Rochester, and St. Thomas More were martyred for their defence of the authority of the Pope in the matter of the King’s divorce and remarriage. Thus, it can be said that the so-called Church of England was the fruit of Henry VIII’s adultery.

- Paul VI, Address to the members of the Secretariat for Christian Unity (headed by Card.Bea), April 28, 1967.

- The movement to make the Papacy more amenable to those outside the fold was given an enormous boost by Pope John Paul II in 1995. In Ut unum sint (§95) he invited dialogue with other faiths to find a way to make the Petrine Ministry “open to a new situation.”

- Pope St Leo I, Sermon 3

- Guéranger, The Liturgical Year, Volume 4, 22 February, Feast of the Chair of St Peter at Antioch

Posted March 18, 2019

______________________

______________________

Volume I |

Volume II |

Volume III |

Volume IV |

Volume V |

Volume VI |

Volume VII |

Volume VIII |

Volume IX |

Volume X |

Volume XI |

Special Edition |