Traditionalist Issues

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Dialogue Mass - XLI

How the Goal of the Eucharistic

Congresses Changed

In his speech at the Assisi Congress in 1956, Fr. Josef Jungmann presented the Mass under two main headings. He characterized the Mass both as an assembly of the people, with the priest as their leader, and as a celebration of the Last Supper, with the main emphasis on the “community meal aspect” (la forme d’un repas en commun”). (1)

These two points, he insisted, were the key to understanding the Mass. Given the influence he exerted over the creation of the Novus Ordo, the definition of the Mass found in Article 7 of the 1969 General Instruction was a foregone conclusion.

The groundbreaking 1960 Eucharistic Congress in Munich

In 1960, when preparations for Vatican II were already under way, Jungmann was given, through the instrumentality of Card. Joseph Wendel of Munich, the opportunity to put his “key” ideas into practice and display them on the world stage. The papal legate Card. Gustavo Testa, 27 Cardinals, 430 Bishops from around the world, approximately 8,000 priests and over a million faithful attended the event. Representatives from other religions were also present, as we shall see later, for “ecumenical” purposes.

Fortunately, the background to the Congress was comprehensively documented, and records exist in the holdings of the Archdiocese of Munich, in contemporary newspaper reports (both German and English) and in the published histories of the events. From these we can gain some insight into the thinking that lay behind the organization of the Congress and the role that Jungmann played in making it the revolutionary event that would change the face of Eucharistic Congresses to this day.

Fortunately, the background to the Congress was comprehensively documented, and records exist in the holdings of the Archdiocese of Munich, in contemporary newspaper reports (both German and English) and in the published histories of the events. From these we can gain some insight into the thinking that lay behind the organization of the Congress and the role that Jungmann played in making it the revolutionary event that would change the face of Eucharistic Congresses to this day.

A hi-jacked Congress

Before looking more closely into the nature of these changes, we will find it useful to study the archival sources that give detailed accounts of the activities of those who organized the event, their meetings, committee members, letters and notes, their hopes and reminiscences. From this documentation we will see, among other things, an enthusiastic endorsement by the young Fr. Joseph Ratzinger – he would have been 33 years old at the time.

First, we gather that the Munich Congress started to be planned more than five years in advance by Card. Wendel during a private audience that Pope Pius XII granted to him. Records show that in 1955, on his way back from the International Eucharistic Congress in Rio de Janeiro, the Cardinal made a stopover in Rome to ask the Pope if he would choose Munich as the place of the next World Congress. That honor, however, had already been allocated to the Portuguese Colony of Mozambique, (2) but Pius XII, under pressure from the German Hierarchy, granted the opportunity to Munich instead. (3)

In 1959, various committees were established to organize the Congress but, it was revealed, all important decisions were taken by Card. Wendel in consultation with a few key collaborators; these included both Jungmann and Guardini, (4) who played a major role in planning the liturgical part of the event.

Jungmann invented the ‘mega-Mass’

The main purpose of International Eucharistic Congresses, since their inception in 1881, (5) had always been to glorify the Holy Eucharist and to bear public witness to the Real Presence of Christ in the Blessed Sacrament. That is why they were characterized by displays of pageantry and dignity in which the procession of the Blessed Sacrament, comprising hundreds of thousands of people, was the most conspicuous feature.

And even though they were open-air events attended by vast crowds, Mass and Benediction were conducted with immense reverence while the people knelt on the ground. In order to safeguard reverence for the Eucharist, Holy Communion was not distributed among the crowds. (6)

But all that was about to undergo a radical transformation in 1960 when Jungmann and his colleagues on Card. Wendel’s Committee planned the Munich Congress in such a way that the whole emphasis lay not in adoration of the Eucharist, but in the celebration of the community.

He afterwards explained: “It is not the Eucharist itself that is the focus of the holy event, but the People of God.” (7)

To reflect this new orientation, a huge “altar island” was constructed in the Theresienwiese (8) for the people to gather round. The Epistle and Gospel were read in German only. Receiving Communion was the obvious climax of the event, while neither reverence nor concern for rubrics was observed. For various eye-witness accounts concur that “a high proportion” of the million attendees “received Holy Communion from hundreds of priests who moved among the wooden benches” and wove their way through the crowds. (9) (Read here and here)

Card. Wendel’s planned self-glorification

Fr. Richard Egenter, who was one of Wendel’s hand-picked members of the steering committee for the Congress (see note 4), stated:

“He [Wendel] saw it as a great moment (Sternstunde), a grace of God’s call, for his archdiocese to do the world a unique service. What had been done in decades of patient and dignified liturgical renewal for German-speaking Catholics should represent the model for the universal Church.” (10)

“He [Wendel] saw it as a great moment (Sternstunde), a grace of God’s call, for his archdiocese to do the world a unique service. What had been done in decades of patient and dignified liturgical renewal for German-speaking Catholics should represent the model for the universal Church.” (10)

Card. Wendel celebrated the opening Mass facing the people at the Odeonsplatz, the square in front of the Feldherrnhalle (the Field Marshalls’ Hall), which was still fresh in the memory of the citizens of Munich as the former “spiritual” centre of the Nazi regime. Hitler had turned the Feldherrnhalle into a memorial for members of the Nazi party; and the Odeonsplatz was the scene for SS parades and commemorative rallies. (11)

From this we gather that Card.Wendel, eager for national glory and with an eye for the main chance, was apparently starry-eyed at the prospect of putting Munich on the world stage in matters liturgical. The German Bishops joined him in rhapsodizing about the “positive results” of the event. (12)

Jungmann as the liturgical Führer

But Jungmann stole his thunder, for it was his name, not Wendel’s, which became permanently associated with the radically new concept of World Eucharistic Congresses. This was officially recognized by the Vatican:

“The first Congress to benefit in a significant way from the influence of the liturgical movement was that of Munich in 1960. From that time on, thanks to the intuition of Josef Andreas Jungmann, Eucharistic Congresses took the form of a Statio [a community gathering]” (13)

Jungmann called his brainchild a Statio Orbis – a “meeting-place of the world” where all were expected to share a communal meal as a sign of unity. This, then, would be the future of the liturgy, as confirmed by the Vatican in 1967:

Jungmann called his brainchild a Statio Orbis – a “meeting-place of the world” where all were expected to share a communal meal as a sign of unity. This, then, would be the future of the liturgy, as confirmed by the Vatican in 1967:

“In the celebration of the Eucharist, a sense of community should be fostered so that all will feel united to their brothers and sisters in the communion of the local and universal Church, and even in a certain way with all humanity.” (14)

A kairos for the Church

The Munich Congress was the opportune and decisive moment or kairos when Church authorities succumbed to the utopian fantasy about the “brotherhood of man” and made it the basis of a new, desacralized liturgy that would replace the traditionally God-centred worship.

The young Fr. Ratzinger stated at the time that Jungmann “has created a new model for the Eucharistic Congresses” that was “revolutionary for the whole Church” as well as being a “preparation for the [upcoming] Council.” (15) [emphasis added]

And Pope John XXIII reportedly described the Congress as “a rehearsal for the Council.”

It is hardly a coincidence that the two conspicuous hallmarks of the Congress, namely, “the gathering” and “the Supper” were also the two defining characteristics of the Novus Ordo, according to its General Instruction of 1969.

Continued

These two points, he insisted, were the key to understanding the Mass. Given the influence he exerted over the creation of the Novus Ordo, the definition of the Mass found in Article 7 of the 1969 General Instruction was a foregone conclusion.

The groundbreaking 1960 Eucharistic Congress in Munich

In 1960, when preparations for Vatican II were already under way, Jungmann was given, through the instrumentality of Card. Joseph Wendel of Munich, the opportunity to put his “key” ideas into practice and display them on the world stage. The papal legate Card. Gustavo Testa, 27 Cardinals, 430 Bishops from around the world, approximately 8,000 priests and over a million faithful attended the event. Representatives from other religions were also present, as we shall see later, for “ecumenical” purposes.

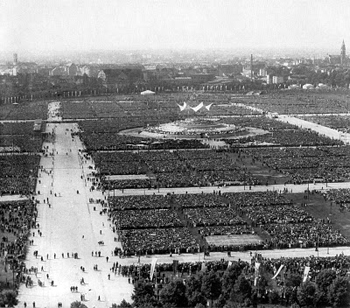

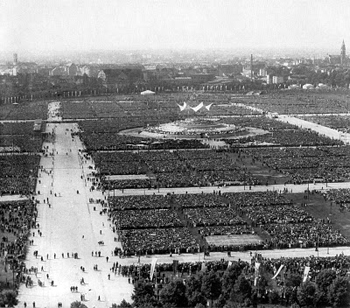

Millions of people exposed to the novelties of the 1960 Munich Congress; below, priests descend the 'altar-island' to distribute Communion among the people

A hi-jacked Congress

Before looking more closely into the nature of these changes, we will find it useful to study the archival sources that give detailed accounts of the activities of those who organized the event, their meetings, committee members, letters and notes, their hopes and reminiscences. From this documentation we will see, among other things, an enthusiastic endorsement by the young Fr. Joseph Ratzinger – he would have been 33 years old at the time.

First, we gather that the Munich Congress started to be planned more than five years in advance by Card. Wendel during a private audience that Pope Pius XII granted to him. Records show that in 1955, on his way back from the International Eucharistic Congress in Rio de Janeiro, the Cardinal made a stopover in Rome to ask the Pope if he would choose Munich as the place of the next World Congress. That honor, however, had already been allocated to the Portuguese Colony of Mozambique, (2) but Pius XII, under pressure from the German Hierarchy, granted the opportunity to Munich instead. (3)

In 1959, various committees were established to organize the Congress but, it was revealed, all important decisions were taken by Card. Wendel in consultation with a few key collaborators; these included both Jungmann and Guardini, (4) who played a major role in planning the liturgical part of the event.

Jungmann invented the ‘mega-Mass’

The main purpose of International Eucharistic Congresses, since their inception in 1881, (5) had always been to glorify the Holy Eucharist and to bear public witness to the Real Presence of Christ in the Blessed Sacrament. That is why they were characterized by displays of pageantry and dignity in which the procession of the Blessed Sacrament, comprising hundreds of thousands of people, was the most conspicuous feature.

And even though they were open-air events attended by vast crowds, Mass and Benediction were conducted with immense reverence while the people knelt on the ground. In order to safeguard reverence for the Eucharist, Holy Communion was not distributed among the crowds. (6)

But all that was about to undergo a radical transformation in 1960 when Jungmann and his colleagues on Card. Wendel’s Committee planned the Munich Congress in such a way that the whole emphasis lay not in adoration of the Eucharist, but in the celebration of the community.

He afterwards explained: “It is not the Eucharist itself that is the focus of the holy event, but the People of God.” (7)

To reflect this new orientation, a huge “altar island” was constructed in the Theresienwiese (8) for the people to gather round. The Epistle and Gospel were read in German only. Receiving Communion was the obvious climax of the event, while neither reverence nor concern for rubrics was observed. For various eye-witness accounts concur that “a high proportion” of the million attendees “received Holy Communion from hundreds of priests who moved among the wooden benches” and wove their way through the crowds. (9) (Read here and here)

Card. Wendel’s planned self-glorification

Fr. Richard Egenter, who was one of Wendel’s hand-picked members of the steering committee for the Congress (see note 4), stated:

Card. Wendell, eager for the spotlight at the Munich event

Card. Wendel celebrated the opening Mass facing the people at the Odeonsplatz, the square in front of the Feldherrnhalle (the Field Marshalls’ Hall), which was still fresh in the memory of the citizens of Munich as the former “spiritual” centre of the Nazi regime. Hitler had turned the Feldherrnhalle into a memorial for members of the Nazi party; and the Odeonsplatz was the scene for SS parades and commemorative rallies. (11)

From this we gather that Card.Wendel, eager for national glory and with an eye for the main chance, was apparently starry-eyed at the prospect of putting Munich on the world stage in matters liturgical. The German Bishops joined him in rhapsodizing about the “positive results” of the event. (12)

Jungmann as the liturgical Führer

But Jungmann stole his thunder, for it was his name, not Wendel’s, which became permanently associated with the radically new concept of World Eucharistic Congresses. This was officially recognized by the Vatican:

“The first Congress to benefit in a significant way from the influence of the liturgical movement was that of Munich in 1960. From that time on, thanks to the intuition of Josef Andreas Jungmann, Eucharistic Congresses took the form of a Statio [a community gathering]” (13)

A table-altar with modern decor facing the people

“In the celebration of the Eucharist, a sense of community should be fostered so that all will feel united to their brothers and sisters in the communion of the local and universal Church, and even in a certain way with all humanity.” (14)

A kairos for the Church

The Munich Congress was the opportune and decisive moment or kairos when Church authorities succumbed to the utopian fantasy about the “brotherhood of man” and made it the basis of a new, desacralized liturgy that would replace the traditionally God-centred worship.

The young Fr. Ratzinger stated at the time that Jungmann “has created a new model for the Eucharistic Congresses” that was “revolutionary for the whole Church” as well as being a “preparation for the [upcoming] Council.” (15) [emphasis added]

And Pope John XXIII reportedly described the Congress as “a rehearsal for the Council.”

It is hardly a coincidence that the two conspicuous hallmarks of the Congress, namely, “the gathering” and “the Supper” were also the two defining characteristics of the Novus Ordo, according to its General Instruction of 1969.

Continued

- J. A. Jungmann, ‘La Pastorale, Clef de L’Histoire Liturgique’ (The Pastoral Approach, Key to the History of the Liturgy) La Maison-Dieu, nn. 47-48, 1956, p. 50

- Having been turned down by the Holy See as the site of next World Congress, Mozambique held its own National Eucharistic Congress in 1956.

- Joseph Wendel, Der Wahrheit und der Liebe (Truth and Love), Würzburg: Arena-Verlag, 1961, p. 63; Peter Pfister, ‘Zwei Hauptfiguren des Eucharistischen Weltkongresses: Erzbischof Joseph Kardinal Wendel und Weihbischof Johannes Neuhäusler’ (The Two Principal Characters in the Eucharistic Congress: Archbishop Joseph Cardinal Wendel and Auxiliary Bishop John Neuhäusler), in Für das Leben der Welt. Der Eucharistische Weltkongress 1960 in München (For the Life of the World. The 1960 International Eucharistic Congress in Munich), Schriften des Archivs des Erzbistums München und Freising 14 (Documents of the Archives of the Archdiocese of Munich and Freising), Regensburg, 2010, p. 47.

- The others were the Auxiliary Bishop of Munich, Johannes Neuhäusler, Franz von Tattenbach, S.J., and the German theologian, Fr. Richard Egenter. See Peter Pfister, Gemeinschaft erleben – Eucharistie feiern Der Eucharistische Weltkongress 1960 in München, (Experience Community. Celebrate the Eucharist. The International Eucharistic Congress in Munich 1960), Archives of the Archdiocese of Munich and Freising, p. 15.

- The First Eucharistic Congress was instituted in 1881 in Lille France, by a lay woman, Emilie Tamisier (1834-1910). Since her childhood, she had a life-long devotion to the Holy Eucharist and had organized pilgrimages to the places where Eucharistic miracles had taken place. Her work was supported by St. Pierre Julian Eymard, the founder of the Blessed Sacrament Fathers and Brothers, and approved by Pope Leo XIII.

- At the International Eucharistic Congress in Dublin in 1932, for example, where about a million people attended the closing Mass, only one person partook of the Sacrament, namely, the celebrant, the Papal Legate Card.Lorenzo Lauri.

- “Nicht die Eucharistie selbst ist das Ziel der göttlichen Heilsveranstaltungen, sondern das Gottes volk.” . Kongressdokumentation Statio Orbis, 1961, (Congress Records) J. A. Jungmann, Statio Orbis Catholici - Heute und Morgen (The Gathering-place for the World’s Catholics – Today and Tomorrow), in R. Egenter, O. Pimer, H. Hofbauer (Eds.), Statio Orbis. Eucharistischer Weltkongreß 1960 in München, 2 vols., Munich, 1962, vol. 1, p. 81.

- A large fairground historically associated with the wedding of Prince Ludwig I of Bavaria and Princess Therese of Sachsen-Hildburghausen which took place there in 1810. It is the site of the annual Oktoberfest, the world’s biggest beer-drinking festival.

- Michael Derrick, “The Eucharistic Congress at Munich,” The Tablet, August, 20, 1960.

- “Er sah darin eine “Sternstunde” seiner Erzdiözese, einen gnadenhaften Anruf Gottes, mit seiner Erzdiözese der Welt einen einmaligen Dienst zu tun. Was in jahrzehntelanger geduldiger und gediegener liturgischer Erneuerungsarbeit von Katholiken deutscher Zunge geleistet worden war”. Apud R. Egenter, “Der Kardinal und der 37. Eucharistische Weltkongress” (The Cardinal and the 37th International Eucharistic Congress), Josef Kardinal Wendel, Der Wahrheit und der Liebe (Truth and Love), Würzburg: Arena-Verlag, 1961, p. 64.

- In 1923 it was the site of the brief battle that ended Hitler’s so-called “Beer Hall Putsch,” his failed attempt to take over Munich as a preliminary to overthrowing the Weimar Republic.

- They saw it as proof that “active and intelligent participation of the faithful” in the Mass was better than “processions and devotional exercises” and as “a convincing example of that universal fraternal charity that must be the necessary fruit of Mass and Communion.” See Augustine Cornides, “The German Scene,” Worship, vol. 35 n. IV 1960-1961, p. 257.

- Piero Marini, The Shape, Significance and Ecclesial Impact of Eucharistic Congresses, June 9, 2009.

- Sacred Congregation of Rites, Instruction on the Worship of the Eucharistic Mystery, 1967, § 18. However, the concern for a supposed unity in communal activity overlooked the fact that the authentic supernatural community of the Church can only be achieved through the union of each individual soul with Christ; and a precondition for that union is prayer and contemplation in an atmosphere of mystery, holiness and reverence.

- The Catholic Academy of Bavaria, Der Eucharistische Weltkongress in MünchenErinnerung, Reflexion, Auftrag (The International Congress in Munich 50 Years Ago, Reminiscence, Reflection, Mission), July 20, 2012.

- “Eine Generalprobe für das Konzil, apud Theodor Schnitzler, ‘Die Gestaltung der Eucharistiefeier im Kongress’ (The Design of the Eucharistic Celebration at the Congress), in R. Egenter, O. Pimer, H. Hofbauer, “Der Kardinal und der 37. Eucharistische Weltkongress”, vol. 1, p. 107

Posted November 23, 2016

______________________

______________________

Volume I |

Volume II |

Volume III |

Volume IV |

Volume V |

Volume VI |

Volume VII |

Volume VIII |

Volume IX |

Volume X |

Volume XI |

Special Edition |