Traditionalist Issues

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Dialogue Mass - XCI

Fourteen Other Feast Days Abolished

One of the most notable – and we are compelled to add grotesque – features of the 1960 reforms is the way in which feasts that had a long and universal acceptance in the Church suddenly became the object of strong disapproval among the members of the Liturgical Commission and their allies in the Church. This was, as we have seen, the case for several feasts that were eliminated after having been in the Universal Calendar for centuries.

What one hand gives the other takes away

The 1960 Rubrics allowed these feasts to be celebrated “in some places.” (1) No sooner had Pope John XXIII’s Rubrics gone into effect in January 1961 than the Congregation of Rites issued an Instruction on February 14 to ensure that their celebration would not be generally adopted on their traditionally observed dates. It specified that this could take place only if “altogether exceptional reasons” (rationes omnino singulares) were given to justify it. (2)

The 1960 Rubrics allowed these feasts to be celebrated “in some places.” (1) No sooner had Pope John XXIII’s Rubrics gone into effect in January 1961 than the Congregation of Rites issued an Instruction on February 14 to ensure that their celebration would not be generally adopted on their traditionally observed dates. It specified that this could take place only if “altogether exceptional reasons” (rationes omnino singulares) were given to justify it. (2)

That set the bar exceedingly high, making it unlikely that the “right” criteria would be fulfilled in most cases, thus discouraging requests to the Holy See from Bishops wishing to retain the traditional dates for their dioceses.

This was just the beginning of a series of increasingly harsh and restrictive measures designed to reduce the majority of feasts in the Universal Calendar.

Local feasts suppressed

In accordance with the February 1961 Instruction, (§§ 32, 33), the following 14 feasts observed in local Calendars were suppressed unless “truly special reasons” required their continued observance.

Pretexts based on erroneous assumptions

First, as these feasts commemorated events in the lives of Our Lord and Our Lady, they drew the faithful into an ever deeper contemplation and union with Christ and His Blessed Mother. But such Catholic devotion was perceived by the Liturgical Movement in general and the members of the Liturgical Commission in particular to be in opposition to a true sense of the liturgy.

The feasts were incorrectly treated as merely by-products of so-called “devotionalism,” as if they were para-liturgical exercises, which during the Middle Ages had been wrongly inserted into the Church’s official liturgy. Many of the faithful, certainly, were devoted to them, but the feasts themselves were – and had been for centuries – an approved part of the liturgy, having their own unique Mass and Propers in the Pro aliquibus locis section of the pre-1962 Missal.

The feasts were incorrectly treated as merely by-products of so-called “devotionalism,” as if they were para-liturgical exercises, which during the Middle Ages had been wrongly inserted into the Church’s official liturgy. Many of the faithful, certainly, were devoted to them, but the feasts themselves were – and had been for centuries – an approved part of the liturgy, having their own unique Mass and Propers in the Pro aliquibus locis section of the pre-1962 Missal.

The unnecessary suppression of these feasts, which, being optional, posed no impediment to the General Calendar, is an example of “clericalism,” the unjustified assertion of dominance of Church leaders over the rights of Tradition. It was the metaphorical equivalent of a wet blanket to dampen the fires of devotion among the faithful.

Second, it makes no sense to suggest that a relatively late origin of a feast (the Middle Ages) constitutes grounds for its suppression. At that rate, many feasts, both local and universal, added after that period would stand condemned. When, however, it suited the reformers’ purposes, they also abolished feasts that had been celebrated in the first centuries of the Church’s existence because they were “too old” to appeal to modern expectations.

The feasts on the above list may have entered the official Calendars in the Middle Ages, but the mysteries they enshrined had been the object of contemplation by the faithful from the early days of Christianity. To take one example, the Holy House of Nazareth where Our Lady received the Annunciation and where the Holy Family lived, was venerated by Christians even in the lifetime of the Apostles; and when St. Helena visited the Holy Land in about 330, she had a church built around the Holy House in order to protect it. (4)

Third, it had never been an accepted custom in the Church to abolish a feast because its theme is similar or identical to that of other feasts in the Calendar. In fact, such “pairings” had always been a feature of the Roman Missal, e.g., Holy Thursday and Corpus Christi, Good Friday and the Precious Blood, the Finding and the Exaltation of the Holy Cross, two feasts for an individual Saint etc.. It was all part of the richness of the pre-1962 Missal, a form of “recapitulation” that helped the faithful to contemplate different aspects of each mystery.

Third, it had never been an accepted custom in the Church to abolish a feast because its theme is similar or identical to that of other feasts in the Calendar. In fact, such “pairings” had always been a feature of the Roman Missal, e.g., Holy Thursday and Corpus Christi, Good Friday and the Precious Blood, the Finding and the Exaltation of the Holy Cross, two feasts for an individual Saint etc.. It was all part of the richness of the pre-1962 Missal, a form of “recapitulation” that helped the faithful to contemplate different aspects of each mystery.

Fourth, it does not follow that because a feast has a special connection with a particular location ‒ whether it be Loreto or Fatima etc. ‒ that it cannot partake of a the universality of the Faith and be of spiritual value to all Catholics around the world. Who would think of abolishing Christmas because it started in Bethlehem, or Good Friday because the Crucifixion took place at a particular spot, Mount Calvary? Why, then, suppress the Translation of the Holy House (10 December), which originated in Nazareth before its miraculous transfer to Loreto?

Yet the Instruction ordered the suppression of this feast on the grounds that its relevance was limited only to a local area (tantum loco particulari), despite the fact that, by 1960, it had been held in veneration on every continent, (5) and was one of the most popular Marian pilgrimage destinations in the world.

Furthermore, with a Decree of March 24, 1920, (6) Pope Benedict XV, inspired by the aerial flight of the Holy House from Nazareth to Loreto, had named the Virgin of Loreto Patroness of aviators and flight attendants. She even achieved iconic status in Space – during the Apollo 9 mission in 1969, the American Astronaut, James McDivitt, wore a medal of Our Lady of Loreto bearing the caption “Protect my Flight.” (7)

Goalposts on wheels

What is striking about the 1961 Instruction is that the rules and requirements of the Calendar reform kept changing this way and that to secure the outcome desired by the progressivist reformers, while making it impossible for the “other side” to score a point. Moving the goalposts would, by any standards, be considered an unfair advantage, a form of cheating – a point of special relevance to the 1960 Calendar reform, as the outcome had already been decided by the plotters on Pius XII’s Liturgical Commission more than a decade earlier.

The secret deliberations of Pius XII’s Liturgical Commission were first made available to the public by Fr. Carlo Braga in 2003. In Chapter 3 of his Memoria sulla Riforma Liturgica, (1948, nn. 134-176), there are references to the Commission’s plans to eliminate “minor” feasts of Our Lord and Our Lady, and feasts “of devotion” in general, especially those of more recent origin.

The secret deliberations of Pius XII’s Liturgical Commission were first made available to the public by Fr. Carlo Braga in 2003. In Chapter 3 of his Memoria sulla Riforma Liturgica, (1948, nn. 134-176), there are references to the Commission’s plans to eliminate “minor” feasts of Our Lord and Our Lady, and feasts “of devotion” in general, especially those of more recent origin.

But the feast of the Expectation of Our Lady (December 18) was neither minor nor recent – it originated in the 7th century and was celebrated with a solemn octave. (8) Its abolition discouraged the liturgical tradition long practised by the faithful, especially expectant mothers, (9) to make a week-long spiritual preparation for the coming of Christ in union with the thoughts of Our Lady as she awaited the birth of her Son.

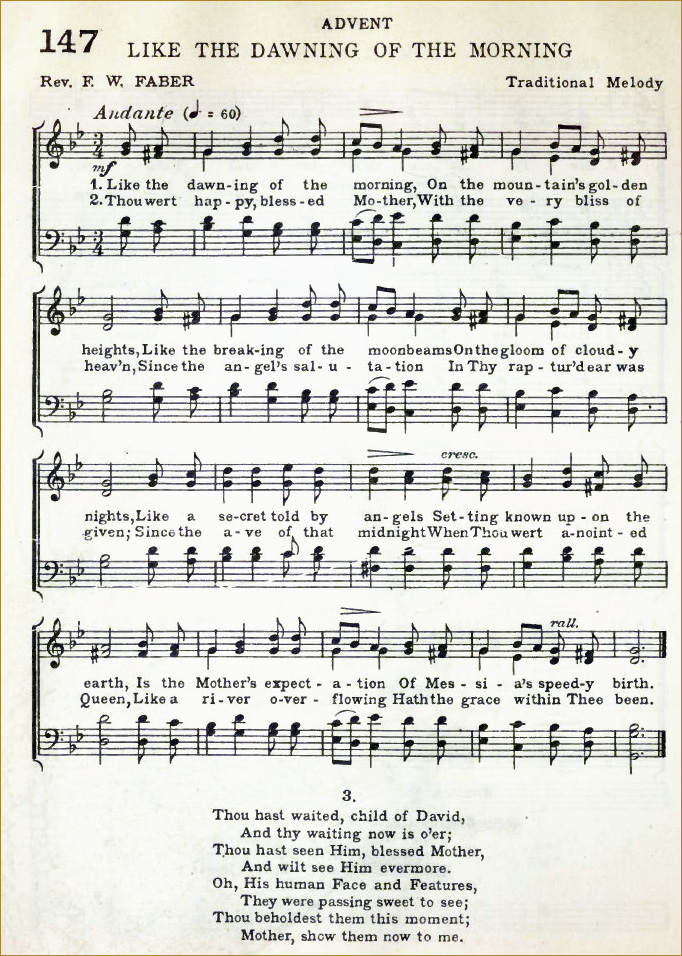

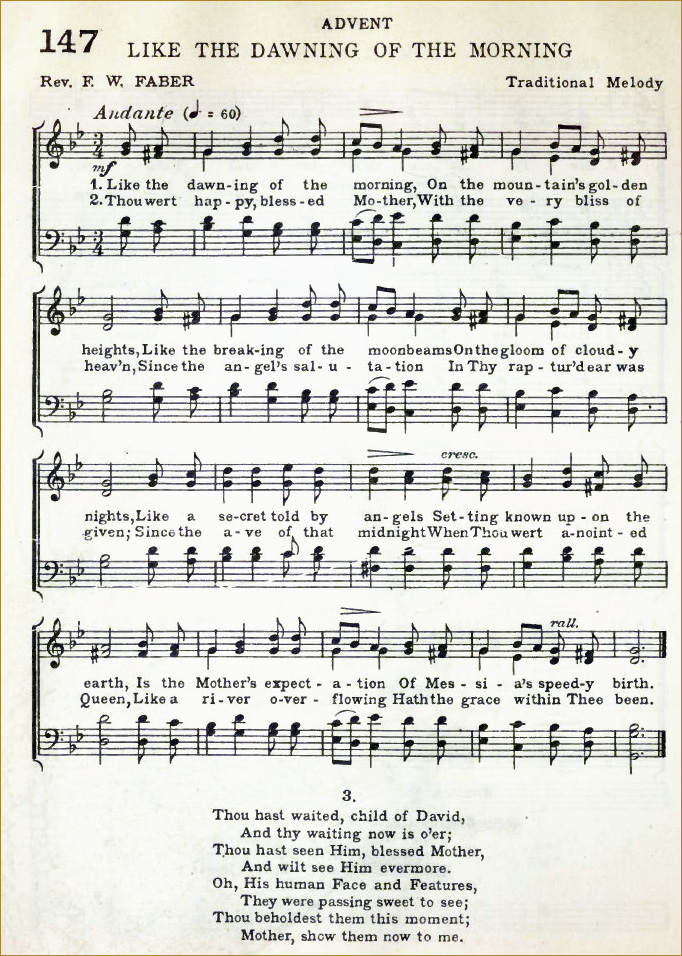

In the 19th century, Fr. Frederick Faber (1814-1863), the noted hymn writer (10) and founder of the London Oratory, composed an Advent carol, which sings of the joy Our Lady felt as the time of her delivery drew near. He gave it the title “Our Lady’s Expectation,” though it was popularly known by its opening words: Like the Dawning of the Morning, and is still remembered as having been sung in Catholic schools at morning Assembly.

But so great was the reformers’ animosity to this devotion – and the feast that celebrates it – that the hymn was excised from the Westminster Hymnal and never saw the light of day in hymn books published after 1960.

‘Bin that!’

The reformers were not moved by considerations of the good of the Church, but by the desire to meet “ecumenical” targets, which are inappropriate for Catholic worship. How treacherous of them to ignore the faithful, trample on their cherished traditions and deprive them of their liturgical patrimony. The contempt with which they did so calls to mind, in modern computer parlance, the “drag and drop” method of discarding unwanted material into the place marked “bin.”

Continued

Continued

What one hand gives the other takes away

A smiling John XIII cuts away traditional feast days

That set the bar exceedingly high, making it unlikely that the “right” criteria would be fulfilled in most cases, thus discouraging requests to the Holy See from Bishops wishing to retain the traditional dates for their dioceses.

This was just the beginning of a series of increasingly harsh and restrictive measures designed to reduce the majority of feasts in the Universal Calendar.

Local feasts suppressed

In accordance with the February 1961 Instruction, (§§ 32, 33), the following 14 feasts observed in local Calendars were suppressed unless “truly special reasons” required their continued observance.

- The Translation of the House of the Blessed Virgin Mary (10 December);

- The Expectation of the Blessed Virgin Mary (18 December);

- The Espousals of the Blessed Virgin Mary to St. Joseph (23 January);

- The Flight of Our Lord into Egypt (17 February);

- The Commemoration of the Passion of Our Lord (Tuesday after Sexagesima Sunday);

- The Holy Crown of Thorns (Friday after Ash Wednesday);

- The Holy Lance and Nails (Friday after the I Sunday in Lent);

- The Holy Shroud (Friday after the II Sunday in Lent);

- The Five Wounds (Friday after the III Sunday in Lent);

- The Most Precious Blood (Friday after the IV Sunday in Lent);

- The Eucharistic Heart of Jesus (Thursday after the Octave of Corpus Christi) (3);

- The Humility of the Blessed Virgin Mary (17 July);

- The Purity of the Blessed Virgin Mary (16 October).

The Flight into Egypt eliminated without reason

- They had originated from the devotion of the faithful (“e privata devotione”), had multiplied exceedingly (“nimis multiplicata sunt”) and invaded the public domain of the liturgy (“in publicum Ecclesiae cultum inducta”);

- They only came into existence from the Middle Ages (“inde a Media Aetate”);

- They duplicated themes that were celebrated at other times of the year (in aliis festis aut anni temporibus);

- They had relevance only to a particular location (cum aliquo tantum loco particulari).

Pretexts based on erroneous assumptions

First, as these feasts commemorated events in the lives of Our Lord and Our Lady, they drew the faithful into an ever deeper contemplation and union with Christ and His Blessed Mother. But such Catholic devotion was perceived by the Liturgical Movement in general and the members of the Liturgical Commission in particular to be in opposition to a true sense of the liturgy.

The Five Wounds illustrate a medieval manuscript

The unnecessary suppression of these feasts, which, being optional, posed no impediment to the General Calendar, is an example of “clericalism,” the unjustified assertion of dominance of Church leaders over the rights of Tradition. It was the metaphorical equivalent of a wet blanket to dampen the fires of devotion among the faithful.

Second, it makes no sense to suggest that a relatively late origin of a feast (the Middle Ages) constitutes grounds for its suppression. At that rate, many feasts, both local and universal, added after that period would stand condemned. When, however, it suited the reformers’ purposes, they also abolished feasts that had been celebrated in the first centuries of the Church’s existence because they were “too old” to appeal to modern expectations.

The feasts on the above list may have entered the official Calendars in the Middle Ages, but the mysteries they enshrined had been the object of contemplation by the faithful from the early days of Christianity. To take one example, the Holy House of Nazareth where Our Lady received the Annunciation and where the Holy Family lived, was venerated by Christians even in the lifetime of the Apostles; and when St. Helena visited the Holy Land in about 330, she had a church built around the Holy House in order to protect it. (4)

Translation of the Holy House from Nazareth to Loreto, celebrated in many paintings

Fourth, it does not follow that because a feast has a special connection with a particular location ‒ whether it be Loreto or Fatima etc. ‒ that it cannot partake of a the universality of the Faith and be of spiritual value to all Catholics around the world. Who would think of abolishing Christmas because it started in Bethlehem, or Good Friday because the Crucifixion took place at a particular spot, Mount Calvary? Why, then, suppress the Translation of the Holy House (10 December), which originated in Nazareth before its miraculous transfer to Loreto?

Yet the Instruction ordered the suppression of this feast on the grounds that its relevance was limited only to a local area (tantum loco particulari), despite the fact that, by 1960, it had been held in veneration on every continent, (5) and was one of the most popular Marian pilgrimage destinations in the world.

Furthermore, with a Decree of March 24, 1920, (6) Pope Benedict XV, inspired by the aerial flight of the Holy House from Nazareth to Loreto, had named the Virgin of Loreto Patroness of aviators and flight attendants. She even achieved iconic status in Space – during the Apollo 9 mission in 1969, the American Astronaut, James McDivitt, wore a medal of Our Lady of Loreto bearing the caption “Protect my Flight.” (7)

Goalposts on wheels

What is striking about the 1961 Instruction is that the rules and requirements of the Calendar reform kept changing this way and that to secure the outcome desired by the progressivist reformers, while making it impossible for the “other side” to score a point. Moving the goalposts would, by any standards, be considered an unfair advantage, a form of cheating – a point of special relevance to the 1960 Calendar reform, as the outcome had already been decided by the plotters on Pius XII’s Liturgical Commission more than a decade earlier.

The ancient feast of Our Lady of the Expection, or The Lady of the O

But the feast of the Expectation of Our Lady (December 18) was neither minor nor recent – it originated in the 7th century and was celebrated with a solemn octave. (8) Its abolition discouraged the liturgical tradition long practised by the faithful, especially expectant mothers, (9) to make a week-long spiritual preparation for the coming of Christ in union with the thoughts of Our Lady as she awaited the birth of her Son.

In the 19th century, Fr. Frederick Faber (1814-1863), the noted hymn writer (10) and founder of the London Oratory, composed an Advent carol, which sings of the joy Our Lady felt as the time of her delivery drew near. He gave it the title “Our Lady’s Expectation,” though it was popularly known by its opening words: Like the Dawning of the Morning, and is still remembered as having been sung in Catholic schools at morning Assembly.

But so great was the reformers’ animosity to this devotion – and the feast that celebrates it – that the hymn was excised from the Westminster Hymnal and never saw the light of day in hymn books published after 1960.

‘Bin that!’

The reformers were not moved by considerations of the good of the Church, but by the desire to meet “ecumenical” targets, which are inappropriate for Catholic worship. How treacherous of them to ignore the faithful, trample on their cherished traditions and deprive them of their liturgical patrimony. The contempt with which they did so calls to mind, in modern computer parlance, the “drag and drop” method of discarding unwanted material into the place marked “bin.”

Fr. Faber's hymn celebrating Our Lady of the Expectation, also cut from Hymnals

- Novum Rubricarum, July 25, 1960, § 305a allowed a Mass to be chosen from the Pro aliquibus locis section of the Roman Missal in place of a Mass from the Commons.

- De calendariis particularibus, AAS 53, 1961, § 34, p. 175. (Emphasis in the original)

- The Octave of this major feast had already been abolished in Pius XII’s reforms.

- St. Paulinus, in Letter 31 to Severus, mentioned that St. Helena had churches built in all the places she visited connected with the principal events of Our Lord’s life; among them he specifically included the place of the Incarnation, which Tradition has identified as the Holy House of Nazareth. (See Paulinus of Nola, Epistolae, Epist. XXXI in Corpus Scriptorum Ecclesiasticorum Latinorum, vol. 29, p. 271)

- This is evident from the proliferation of churches, chapels, schools, colleges and religious institutes dedicated to the Virgin of Loreto throughout the world, and from the popularity of the Litany of Loreto among the faithful.

- B. Maria Virgo Lauretana Aëreonautarum Patrona Declaratur, AAS 12, March 24, 1920, p. 175.

- The American Autograph Auction, RR Auctions, has an authenticated record of this medal. The reverse depicts an aeroplane encircled by text reading, “Patroness of Aviators & Air Travellers.” The medal is accompanied by a signed letter of provenance from James McDivitt stating: “I certify that this Our Lady of Loretto [sic] medallion was flown on board Apollo 9 on her flight in March, 1969. It is from my personal collection.”

- It originated in Spain at the Tenth Council of Toledo (656) and was gradually conceded to other countries. The octave was from December 17 with the great ‘O’ Antiphons for the Magnificat at Vespers to December 24.

- Dom Guéranger asserted: “A High Mass was sung at a very early hour each morning during the octave, at which all who were with child, whether rich or poor, considered it a duty to assist, that they might thus honor Our Lady’s Maternity and beg Her blessing upon themselves. It is no wonder that the Holy See approved of this pious practice being introduced into almost every other country.” (The Liturgical Year, Dublin, 1870. vol. 1, p. 514)

This feast would have had particular relevance in the modern world to reinforce respect for motherhood and the unborn child in the combat against the scourge of abortion. - Among his best loved hymns are: Faith of our fathers, Jesus Gentlest Saviour, Jesus my Lord, my God, my all, O Purest of Creatures, Sweet Mother, Sweet Maid , and Oh, come and mourn with me awhile.

Posted September 16, 2019

______________________

______________________

Volume I |

Volume II |

Volume III |

Volume IV |

Volume V |

Volume VI |

Volume VII |

Volume VIII |

Volume IX |

Volume X |

Volume XI |

Special Edition |