Traditionalist Issues

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Dialogue Mass - XXXVI

Like the Protestants, Progressivists Mock

the Elevation

It is interesting to see how satire and caricature fuelled both the Protestant “Reformation” of the 16th century and the Liturgical Revolution of the 20th. Both movements sought through these means to create a climate of scepticism towards the supernatural, break down respect for the sacrality of Tradition and destroy attachment to the medieval rites, particularly those that honored the Blessed Sacrament.

Historical evidence shows that Protestants of the “Reformation” era habitually ridiculed the Elevation with satirical tales intended to make a mockery of the practice of adoring the Host and to link it with superstition.

Jungmann treated the Elevation as a joke

Fr. Josef Jungmann seemed to gloat over these scurrilous tales, judging by the evident delight he took in repeating them as if they were historically verifiable facts. For example, with reference to the Elevation, he stated:

“It could happen – as it did in England – that if the celebrant did not elevate the Host high enough, the people would cry out: ‘Hold up, Sir John (1), hold up. Heave it a little higher.’” (2)

“It could happen – as it did in England – that if the celebrant did not elevate the Host high enough, the people would cry out: ‘Hold up, Sir John (1), hold up. Heave it a little higher.’” (2)

The credibility of such a tale is seriously compromised by the fact that it had been written as a burlesque of Catholic piety by Thomas Becon, chaplain to Archbishop Thomas Cranmer and one of the most aggressive 16th century polemicists, notorious for his crudely expressed anti-Catholic insults. (3) See here.

Insofar as Jungmann knowingly suppressed the context of this parody of the Elevation (4) and presented it instead as a historical record, he can be accused of deliberately misreading the past to justify the perpetration of future reforms.

If sarcasm (5) can be described as contempt disguised by humor, Jungmann’s true attitude to the Elevation is manifested in these words:

“There are examples of congregations where the majority of the faithful waited for the sance-bell [Sanctus bell] signalling the approach of the Consecration before they entered the church and, then, after the elevation they rushed out as quickly as they had come in... fleeing as if they had seen the devil.” (6)

One could say that he had a diabolical sense of humor

Jungmann derided the Elevation, describing it as a fetish

The underlying message was that the Elevation, accompanied as it was by the ringing of bells, (7) was problematic because it caused a stampede of the faithful in and out of the church. But, his opinion can be shown to be merely a cum hoc fallacy. (8)

Also, the image he cultivated of the Elevation as something of a spectator sport with crowds of people racing from church to church just to catch a glimpse of it (9) is now a running joke – pun unintended – among modern liturgists and is the standard view of the Elevation promoted in modern histories and encyclopaedias.

Also, the image he cultivated of the Elevation as something of a spectator sport with crowds of people racing from church to church just to catch a glimpse of it (9) is now a running joke – pun unintended – among modern liturgists and is the standard view of the Elevation promoted in modern histories and encyclopaedias.

We must remember, however, that a few reports of such behavior, even where they corresponded with reality, are often exaggerated as if they were the common custom, especially by historians who approach their subject with preconceptions; and that it is only the exceptions and irregularities which attracted attention at the time that are recorded for future generations, while the everyday examples of humble obedience and unobtrusive piety escape the satirist’s pen.

Unfortunately, Jungmann had the potential to shape the “popular” conception of the medieval liturgy by appealing to the worst tendencies in his readers, including the desire to scoff at the holy, even the Holy of Holies.

Jungmann continued to surround the Elevation with an atmosphere of jest and amusement:

“To look at the sacred Host at the elevation became for many in the later Middle Ages the be-all and end-all of Mass devotion. See the Body of Christ at the Consecration and be satisfied!” (10)

His opinion shows a certain disdain or, at the very least, a lack of respect for the faith of medieval Catholics whom he accused of regarding the Elevation as a “substitute for sacramental Communion”.

‘The gaze’

Jungmann was determined to tarnish the ritual of the Elevation by suggesting the “showing” of the Host was inspired by the popular medieval folk legend, the Grail, which featured a supposedly magical power of the act of seeing:

“To see the celestial mystery, that is the climax of the Grail-legend in which, at this same period, the religious longing of the Middle Ages found its poetic expression ... And as in the Grail-legend many grace-filled results were expected from seeing the mystery, so too at Mass.” (12) [emphasis added]

“To see the celestial mystery, that is the climax of the Grail-legend in which, at this same period, the religious longing of the Middle Ages found its poetic expression ... And as in the Grail-legend many grace-filled results were expected from seeing the mystery, so too at Mass.” (12) [emphasis added]

He virtually accused the faithful of believing that, just as in the Grail legend material benefits were thought to be magically guaranteed through direct eye contact with the object of their devotion, so also looking at the Host could produce the same effects. “There is a startling parallel here,” he averred, (13) and concluded that, in the opinion of medieval Catholics, looking at the Host was more beneficial than receiving. (14)

'Ocular Communion'

It is merely the wildest speculation that medieval Mass-goers thought of the Elevation in this way. There was never any such thing as “ocular Communion” (an expression still current among modern liturgists to ridicule the Elevation) as distinct from the pious practice of “spiritual Communion.” Every well-instructed Catholic knew that the grace of the Sacrament was wrought by Christ, not by the action of seeing and that merely looking at the Host would not be spiritually efficacious without an accompanying intention of adoration.

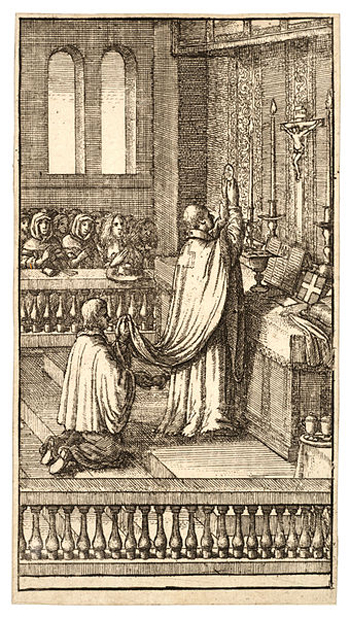

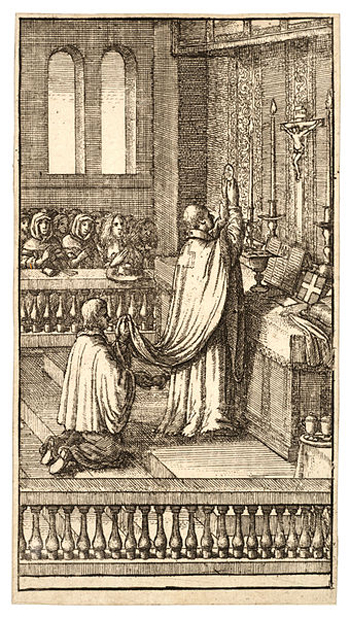

This is why, in their pastoral and catechetical instructions, the clergy exhorted the faithful to venerate the Host at the Elevation. And there were many manuals of devotion for lay people, complete with a variety of prayers as an aid to contemplation during the Consecration e.g. this beautiful 13th century

prayer of William Durandus, Bishop of Mende, contained in his diocesan Instructions. (15)

This is why, in their pastoral and catechetical instructions, the clergy exhorted the faithful to venerate the Host at the Elevation. And there were many manuals of devotion for lay people, complete with a variety of prayers as an aid to contemplation during the Consecration e.g. this beautiful 13th century

prayer of William Durandus, Bishop of Mende, contained in his diocesan Instructions. (15)

It is of the greatest significance that the jibe about “ocular Communion,” which is prevalent among modern liturgists, originated from medieval Protestant objections to the Elevation as a form of superstition. This was the theme of a satire of the Mass by George Hakewill, a 16th century Church of England clergyman and a virulent anti-Catholic polemicist, in which he called the Mass an “eye-service”:

“OUR adversaries [the Catholics] indeed place a great and main part of their superstitious worship in the eye-service; in the magnificent & pompous fabric and furniture of their Churches and attiring their Priests; in gazing upon their dumb ceremonies … in beholding the daily elevation of their Idol in the Mass, (for the greatest part hear nothing)” (16)

From Jungmann’s perspective, the medieval liturgy was a magnificent spectacle put on by the priests for a mute and highly superstitious audience.

Misdirected criticism

But the charge of superstition against the medieval faithful regarding the Mass in general and the Elevation in particular cannot be maintained. For the medieval hierarchy, unlike the progressivists in the Church today who support and encourage New Age theories, voodoo etc., strove to correct and control all superstitious elements among the faithful. (17)

Continued

Historical evidence shows that Protestants of the “Reformation” era habitually ridiculed the Elevation with satirical tales intended to make a mockery of the practice of adoring the Host and to link it with superstition.

Jungmann treated the Elevation as a joke

Fr. Josef Jungmann seemed to gloat over these scurrilous tales, judging by the evident delight he took in repeating them as if they were historically verifiable facts. For example, with reference to the Elevation, he stated:

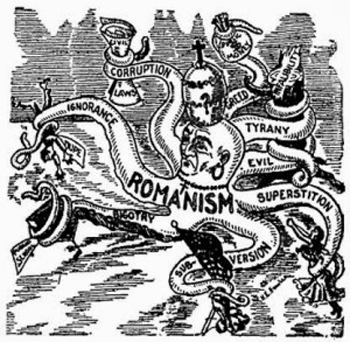

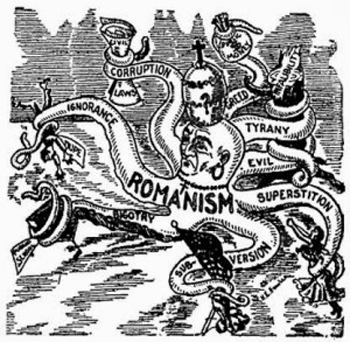

Protestant satire ridiculing ‘Romanish’ superstitions and institutions

The credibility of such a tale is seriously compromised by the fact that it had been written as a burlesque of Catholic piety by Thomas Becon, chaplain to Archbishop Thomas Cranmer and one of the most aggressive 16th century polemicists, notorious for his crudely expressed anti-Catholic insults. (3) See here.

Insofar as Jungmann knowingly suppressed the context of this parody of the Elevation (4) and presented it instead as a historical record, he can be accused of deliberately misreading the past to justify the perpetration of future reforms.

If sarcasm (5) can be described as contempt disguised by humor, Jungmann’s true attitude to the Elevation is manifested in these words:

“There are examples of congregations where the majority of the faithful waited for the sance-bell [Sanctus bell] signalling the approach of the Consecration before they entered the church and, then, after the elevation they rushed out as quickly as they had come in... fleeing as if they had seen the devil.” (6)

One could say that he had a diabolical sense of humor

Jungmann derided the Elevation, describing it as a fetish

The underlying message was that the Elevation, accompanied as it was by the ringing of bells, (7) was problematic because it caused a stampede of the faithful in and out of the church. But, his opinion can be shown to be merely a cum hoc fallacy. (8)

Jungmann ridicules the people who eagerly awaited the moment of elevation

We must remember, however, that a few reports of such behavior, even where they corresponded with reality, are often exaggerated as if they were the common custom, especially by historians who approach their subject with preconceptions; and that it is only the exceptions and irregularities which attracted attention at the time that are recorded for future generations, while the everyday examples of humble obedience and unobtrusive piety escape the satirist’s pen.

Unfortunately, Jungmann had the potential to shape the “popular” conception of the medieval liturgy by appealing to the worst tendencies in his readers, including the desire to scoff at the holy, even the Holy of Holies.

Jungmann continued to surround the Elevation with an atmosphere of jest and amusement:

“To look at the sacred Host at the elevation became for many in the later Middle Ages the be-all and end-all of Mass devotion. See the Body of Christ at the Consecration and be satisfied!” (10)

His opinion shows a certain disdain or, at the very least, a lack of respect for the faith of medieval Catholics whom he accused of regarding the Elevation as a “substitute for sacramental Communion”.

‘The gaze’

Jungmann was determined to tarnish the ritual of the Elevation by suggesting the “showing” of the Host was inspired by the popular medieval folk legend, the Grail, which featured a supposedly magical power of the act of seeing:

Jungmann uses the Grail legend to denigrate the Elevation

He virtually accused the faithful of believing that, just as in the Grail legend material benefits were thought to be magically guaranteed through direct eye contact with the object of their devotion, so also looking at the Host could produce the same effects. “There is a startling parallel here,” he averred, (13) and concluded that, in the opinion of medieval Catholics, looking at the Host was more beneficial than receiving. (14)

'Ocular Communion'

It is merely the wildest speculation that medieval Mass-goers thought of the Elevation in this way. There was never any such thing as “ocular Communion” (an expression still current among modern liturgists to ridicule the Elevation) as distinct from the pious practice of “spiritual Communion.” Every well-instructed Catholic knew that the grace of the Sacrament was wrought by Christ, not by the action of seeing and that merely looking at the Host would not be spiritually efficacious without an accompanying intention of adoration.

Adoration of the sacred species: another ‘eye service’

It is of the greatest significance that the jibe about “ocular Communion,” which is prevalent among modern liturgists, originated from medieval Protestant objections to the Elevation as a form of superstition. This was the theme of a satire of the Mass by George Hakewill, a 16th century Church of England clergyman and a virulent anti-Catholic polemicist, in which he called the Mass an “eye-service”:

“OUR adversaries [the Catholics] indeed place a great and main part of their superstitious worship in the eye-service; in the magnificent & pompous fabric and furniture of their Churches and attiring their Priests; in gazing upon their dumb ceremonies … in beholding the daily elevation of their Idol in the Mass, (for the greatest part hear nothing)” (16)

From Jungmann’s perspective, the medieval liturgy was a magnificent spectacle put on by the priests for a mute and highly superstitious audience.

Misdirected criticism

But the charge of superstition against the medieval faithful regarding the Mass in general and the Elevation in particular cannot be maintained. For the medieval hierarchy, unlike the progressivists in the Church today who support and encourage New Age theories, voodoo etc., strove to correct and control all superstitious elements among the faithful. (17)

Continued

- In medieval England, priests were commonly addressed as Sir, a courtesy title also given to knights. The obvious intent here is one of unreserved mockery, which was common among the leaders of the “Reformation.” For example, in the Works of James Pilkington, Bishop of Durham from 1561-1575, we read that he called priests “Sir John Lack-Latin” (p. 20), “Sir John Smell-smoke” (a reference to the use of incense) (p. 255), and “Sir John Mumble-matins” (p. 26). He also referred to them as “the Popes’s oiled shavelings” (tonsured clerics anointed with holy oils) (p. 82), and “the Pope’s belly-gods” (gluttons) (p. 580). He described the Catholic Bishops as “the Pope’s horned cattle” (p. 664) in allusion to their mitres; monks were “abbey lubbers” (a medieval word for swindlers, parasites) (passim); he renamed Hildebrand (Pope St. Gregory VII) as “Hell-brand” (p. 565); he called St. Thomas of Canterbury a “stinking martyr” (p. 65) and Cardinal Pole a “Carnal Fool” (p. 77); he said Purgatory was “the Pope’s scalding house” (p. 497), and execrated the Holy Mass as “the popish clouted [clothed i.e. with vestments] Latin Mass” (p. 496).

- J. Jungmann, The Mass of the Roman Rite, vol. 1, p. 121, note 101.

- Thomas Becon, ‘Displaying of the Popish Mass’ in Prayers and other pieces of Thomas Becon, Publication of the Parker Society, edited by Rev. John Ayre, Cambridge University Press, 1844, vol. 3, p. 270. In the same essay, he called priests “mass mongers” and the Mass an “abominable idol-service” (p. 253); he wrote of “anti-Christ’s brood of Rome” (p. 259) and the “idolatrous priests of Babylon” (p. 261). Becon especially detested the Elevation: “And although the whole mass of the papists be utterly wicked and abominable, yet this part, which they call the sacring, is most wicked and abominable; forasmuch as it provoketh the people that are present to commit most detestable idolatries.” (p. 270)

- J. Jungmann, The Mass of the Roman Rite, note 101, quoted from the respected Catholic historian, Fr. Adrian Fortescue, The Mass, A Study of the Roman Liturgy, p. 341, but omitted Fortescue’s explanation that Becon was using this tale for the purposes of “attacking the Mass.”

- “Sarcasm” can be traced back to the Greek word sarkasmos, a cutting or wounding remark, which in turn derives from sarkazein, meaning to tear flesh like a dog. Its use here seems apposite in the sense that treating the Consecration with contempt is tantamount to lacerating the flesh of Christ.

- J. Jungmann, The Mass of the Roman Rite, vol 1, p. 121, note 102.

- The Council of Trent mandated the use of bells at the Elevation during Consecration (not to mention at other parts of the Mass), but only after the custom had already been established for 350 years. After 750 years’ use of bells during the Mass, the custom was made optional in the Novus Ordo reform, and fell into almost complete desuetude. The reason for its unpopularity in the Liturgical Movement was the progressivist belief that the Eucharistic Prayer was a consecratory, seamless whole and should not be interrupted by the sound of bells, which mark a precise moment of Consecration.

- The Latin phrase cum hoc ergo propter hoc means, literally, “with this, therefore, because of this.” Jungmann committed the cum hoc fallacy by assuming – or rather getting the reader to assume – that because the unruly behaviour occurred just before and immediately after the Elevation, it must have occurred because of it. Although there is a correlation between the two events, Jungmann has failed to prove a causal connection between them. Nor did he take into consideration other factors that influenced the irreverent behaviour, such as a worldly and lukewarm attitude to the Faith. In every era there were some half-hearted Catholics who arrived late (some time after the sermon) and left early (around Communion time), which roughly corresponds to the Canon of the Mass. A survey carried out in the 1950s in a parish in Vienna (a city with which Jungmann was familiar) revealed that about 30 % of the congregation arrived late and left before or just after Communion, in addition to which a “sizeable number” hung around the doorway of the church, smoking and talking. See B. Ziemann, Encounters with Modernity: The Catholic Church in West Germany, 1945-1975, Berghahn Books, 2014, p. 39.

- “In the cities people ran from church to church, to see the elevated Host as often as possible.” J. Jungmann, The Mass of the Roman Rite, vol 1, p. 121.

- Ibid.

- Ibid., p. 120.

- Ibid.

- Ibid., note 97.

- In order to support this hypothesis, Jungmann referenced the work of the German liturgical historian, Fr. Anton L. Mayer, a disciple of Abbot Ildefons Herwegen of the Benedictine Monastery Maria Laach. In 1938, Fr. Mayer had written a book-length essay for Dom Herwegen, entitled “Die heilbringende Schau in Sitte und Kult” (The Grace-giving Gaze in Custom and Cult). In it, he posited that the medieval faithful believed that during the Elevation their eyes emitted magical rays by means of which they could “touch” the Host and that a range of benefits could be transmitted back from the Host along the same pathway. (ibid., pp. 235-236) For this fanciful theory he invented the term “Schaudevotion” (devotional viewing) and blamed it for reducing the congregation to silent spectators instead of active participants. His book was edited by Dom Odo Casel, also of Maria Laach, and exerted a continuing influence on the Liturgical Movement. See Anton L. Mayer, “Die heilbringende Schau in Sitte und Kult” in Heilige Überlieferung: Ausschnitte aus der Geschichte des Mönchtums und des heiligen Kultes (Festschrift für Ildefons Herwegen), Münster: Aschendorff Verlag, 1938, pp. 234-241.

- “Furthermore, when the Body of Christ is shown to the people to be adored thus, reverently kneeling, they should say: O most precious Body of Christ, true God and true man, Who art the Price and Reward, the Salvation King and Light of the world, whom every creature together justly praises and blesses, to Thee I devoutly commend my body and soul, suppliantly and earnestly beseeching that to me and all my relatives, parents, friends and benefactors, Thou mayest vouchsafe to grant spiritual and temporal peace, joy also, and all things needful for health of soul and body; moreover [vouchsafe to grant us] the heart, time and opportunity to repent and serve Thee worthily and laudably; and protect us from shame, want and sudden death, and from every adversity of mind and body, and also to have mercy upon us and all the faithful, both the living and the dead.” [translation by C. Byrne] (J. Berthelé and M. Valmary (eds.), Instructions et Constitutions de Guillaume Durand, Montpellier, 1900, pp. 79-80)

- George Hakewill 1578-1649. The Vanity of the Eye, chapter 25, ‘That the popish religion consists more in eye service than the reformed’, 1608, pp. 125-126. [The spelling in the original Middle English version has been modernized for the sake of clarity]

- Medieval theologians relied heavily on the Church Fathers and the towering figure of St. Thomas Aquinas who denounced all superstitious practices as an infringement of the First Commandment. St. Augustine taught that superstition entailed pacta cum daemonibus (pacts with the devils) and was the antithesis of true religion; and St. Thomas Aquinas took up the same theme and linked it with heresy.

Posted July 11, 2016

______________________

______________________

Volume I |

Volume II |

Volume III |

Volume IV |

Volume V |

Volume VI |

Volume VII |

Volume VIII |

Volume IX |

Volume XI |

Special Edition |

Special Edition |