Traditionalist Issues

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Dialogue Mass - CXXXVII

Sudden Demise of the ‘Manualist Tradition’

after Vatican II

How exactly the theological Manuals suddenly fell from grace, and were just as suddenly reduced to the status of mere quisquiliae (useless things to be discarded) after being hallowed by long tradition, is not a subject generally known today, even among traditionalists. We can take it as true that most priests do not know how and why they disappeared, and show little interest in finding out. They prefer, apparently, to cling to the unflattering portraits repeated by progressivists that depict the Manuals as a blot on the Church’s intellectual landscape.

Few post-Vatican II conservative-leaning Catholics realize that Fr. Joseph Ratzinger, in collaboration with Fr. Karl Rahner, was the main theologian in the opening months of the Council who rejected most of the initial draft documents, and who demanded that they be reworked to suit modern sensibilities. It is important to keep in mind that these official drafts, prepared by the Central Preparatory Commission under the direction of Card. Ottaviani, were based on the authentic Catholic doctrines taught by pre-Vatican II Popes, which crucially, represented the theological content of the seminary text-books or Manuals.

Before going on, a further point needs to be made on this subject. Ratzinger was in the strongest position to exert immense influence on the formulation of the Council documents because he was the personal adviser to Card.Frings, Head of the German Bishops’ Conference. He rejected the “Manualist tradition” in favor of greater theological freedom to reformulate doctrine. In his Introduction to Christianity, first published in 1968, he made a harsh denunciation of “fixed formulas” (an oblique reference to the “Manualist tradition”) and their use in passing on the Faith to future generations. Ratzinger stated:

Before going on, a further point needs to be made on this subject. Ratzinger was in the strongest position to exert immense influence on the formulation of the Council documents because he was the personal adviser to Card.Frings, Head of the German Bishops’ Conference. He rejected the “Manualist tradition” in favor of greater theological freedom to reformulate doctrine. In his Introduction to Christianity, first published in 1968, he made a harsh denunciation of “fixed formulas” (an oblique reference to the “Manualist tradition”) and their use in passing on the Faith to future generations. Ratzinger stated:

“[Modern disbelief] cannot be countered by merely sticking to the precious metal of the fixed formulas of days gone by, for then it remains just a lump of metal, a burden instead of something offering by virtue of its value the possibility of true freedom. This is where the present book comes in: its aim is to help understand faith afresh as something that makes possible true humanity in the world of today, to expound faith without changing it into the small coin of empty talk painfully laboring to hide a complete spiritual vacuum.” 1

As he mentioned in the Preface, the content of his book was taken from a lecture he gave in 1967 to students at the University of Tübingen. Paradoxically, he seems to have considered that his role as Professor was to teach them to despise the “Manualist tradition.” For that is the inevitable outcome of denouncing as a now useless anachronism the Church’s revered (and highly successful) Scholastic method of teaching the Faith with Manuals.

Ratzinger’s complicity with radical revolution

Prof. Ratzinger’s 1967 lecture could not have come at a worse time. West Germany was at the centre of the European student protest movement of 1968, and was led by the Socialist student activist, Rudi Dutschke. (It was he, incidentally, who formulated the term, “Long March through the Institutions” as a strategy for working against established structures while working within them).

Many students at the University of Tübingen, where Ratzinger had been teaching for two years, were among those who took an active part in the ensuing widespread riots, violence and destruction. Their rebellion was essentially a protest against all “fixed formulas” (as found, for instance, in Humanae vitae which was a particular flashpoint) that supported patriarchal structures, lifestyle patterns and traditional morals operating in the Church and society.

As with similar lectures by his contemporaries, Fr. Karl Rahner and Fr. Hans Küng, Prof. Ratzinger’s were packed with hundreds of radicalized students attracted like bees to a honey pot. (In later life, he put a euphemistic gloss on his popularity with the students by saying that they “reacted enthusiastically to the new tone they thought they heard in my words.”) 2

But what they actually heard and reacted to was a new theological orientation that would justify their revolutionary impulses for “liberation,” and help them devise plans for radical action in the Church and society. This sort of anti-authority rebellion is amply demonstrated to have been the case in the 1968 student movement in Germany.3 Moreover, it cannot be denied that all three progressivist theologians – Ratzinger, Rahner and Küng – exploited the relatively immature intellectual development and gullibility of young people, for the most part still in their teens, to pump them with anti-traditional propaganda by presenting opinion as fact.

But what they actually heard and reacted to was a new theological orientation that would justify their revolutionary impulses for “liberation,” and help them devise plans for radical action in the Church and society. This sort of anti-authority rebellion is amply demonstrated to have been the case in the 1968 student movement in Germany.3 Moreover, it cannot be denied that all three progressivist theologians – Ratzinger, Rahner and Küng – exploited the relatively immature intellectual development and gullibility of young people, for the most part still in their teens, to pump them with anti-traditional propaganda by presenting opinion as fact.

Ratzinger’s determination to rid the Church of “fixed formulas” ‒ which had acted as the glue that helped keep the Christian order of Church and society from dissolution ‒ did nothing to improve the situation, and even helped to fan the flames of revolt. With so much pressure from all sides for “emancipation,” the University descended into a maelstrom of revolution and radical theology, and the Church itself followed suit, fracturing in the process its common bonds of tradition, custom, culture and morality.

This parlous situation can be seen as an early stage of the abdication of clerical authority that would become evident after Vatican II when bishops and priests simply gave up the fight for the interests of the Church against revolutionary forces that sought to destroy her. There can be no doubt that keeping the “Manualist tradition” with its “fixed formulas” would have been a sure bulwark against the revolution.

Mid-20th century crisis of the 'Manualist tradition' in seminaries

Referring to his own seminary days, Ratzinger commented with obvious relish:

“All of us lived with a feeling of radical change that had already arisen in the 1920s, the sense of a theology that had the courage to ask new questions and a spirituality that was doing away with what was dusty and obsolete and leading to a new joy in the redemption.” 4

His opinion that “courage” was needed to ask new theological questions in the early 20th century was a veiled critique of the Roman authorities who were attempting to crush the Modernist movement. He did not distinguish between questioning as enquiry (as in “faith seeking understanding”) and questioning as implying either doubt or outright incredulity (as in Modernism’s scepticism towards accepted doctrine). And yet the distinction is crucial, for right understanding and effective communication of ideas always involve making careful distinctions, as he would have found in the Manuals, had he consulted them.

The point of Ratzinger’s opinion was obviously to reinforce the usual progressivist stereotype of the pre-Vatican II Church as a hidebound, obscurantist institution propping up a tyrannical regime that suppresses progress by stifling intellectual enquiry and debate. What he failed to appreciate was that the Scholastic method of explaining the Faith does not require people to refrain from asking questions; but it does prevent them from arriving at wrong answers in the sense of drawing conclusions from initial premises that are contrary to Catholic principles.

In fact, the value and legitimacy of asking questions were always recognized in the Church. St. Thomas’s Summa, for instance, was constructed on that method: it contains as many questions as there are answers. Then there were the great Disputationes and Controversiae of the Counter-Reformation period which were dedicated to solving quaestiones about theological matters. These gave rise to much intellectual ferment and debate, all of which was subsumed in the Scholastic system, eventually emerging in the “Manualist tradition.”

The Church, then, never had a problem with asking questions. The problem was with progressivist theologians who did not want to hear the answers.

Ratzinger’s attraction to turn-of-the-century progressivist theology (of the kind dubbed “Modernism” and condemned by Pope Pius X) was a key factor in his dismissal of “fixed formulas” found in the dusty old tomes of the “Manualist tradition.” Like his fellow neo-modernists, he was intoxicated by the prospect of the exciting new developments in theology that would open new horizons for him and satisfy his thirst for novelty. The leading progressivist theologian of Pius XII’s time, Henri de Lubac SJ, attained hero status in his eyes: he, too, scorned the Scholastic tradition found in the Manuals.

Then there were de Lubac’s companions – Chenu, Congar, Daniélou – who were particularly active in promoting “ressourcement” theology in the 1940s, and with whom Ratzinger collaborated in their efforts to dethrone Scholastic theology.

Then there were de Lubac’s companions – Chenu, Congar, Daniélou – who were particularly active in promoting “ressourcement” theology in the 1940s, and with whom Ratzinger collaborated in their efforts to dethrone Scholastic theology.

In addition to these French sources, Ratzinger adds in his Memoirs a Pléiade of contemporary German progressivist theologians 5 who exerted a fundamental influence on his thinking. These included his professor of Moral Theology, Fr, Richard Egenter and his colleagues who were seeking “to end the dominance of casuistry and the Natural Law” and would allow people to “to rethink morality on the basis of the following of Christ.” 6

Unsurprisingly, they all rejected the “Manualist tradition.” The Bible, rather than Tradition, would be the guiding rule. This is enough to show that Ratzinger belonged to a bohemian fringe of theologians who rallied against mainstream theology and challenged dominant values in the Church.

The inescapable conclusion is that Ratzinger was on the side of the neo-modernists who want unlimited academic freedom rather than submit their intellects to the authority of the Hierarchy in matters of revealed doctrine. This is confirmed by his observation that, at the beginning of the Council, Pope John XXIII “by the force of his personality” had infused the proceedings with a “holy freedom” and a new spirit of “openness and candor.” He saw this turn-around as a catharsis in the sense that “the anti-modernistic neurosis that had again and again crippled the Church since the turn of the century here seemed to be approaching a cure.” 7

Ratzinger’s image of Pope John XXIII as a smiling, avuncular figure dispensing liberal amounts of good cheer at the Council has a deeper significance. First, it was Ratzinger himself who played a major role before and during the Council to change its tone, mood and orientation. 8 There is evidence that he single-handedly drew up the blueprint for Vatican II when he composed a lecture for Card. Frings to deliver in Genoa in November 1961 at a Conference on the Church in the Modern World. 9

Ratzinger’s image of Pope John XXIII as a smiling, avuncular figure dispensing liberal amounts of good cheer at the Council has a deeper significance. First, it was Ratzinger himself who played a major role before and during the Council to change its tone, mood and orientation. 8 There is evidence that he single-handedly drew up the blueprint for Vatican II when he composed a lecture for Card. Frings to deliver in Genoa in November 1961 at a Conference on the Church in the Modern World. 9

According to Frings’s biographer, Fr. Norbert Trippen, John XXIII was so pleased with its contents and tone that he declared it to be entirely compatible with his own intentions for the Council. 10 Anyone who reads the Lecture (a translation of selected passages into English is also available) 11 can see an exact correspondence at several points with the text of John XXXIII’s Opening Speech, Gaudet Mater Ecclesia. Interestingly, Romano Amerio who was a peritus at the Council, detected the hand of a hidden author:

“The opening speech of the Council … is a complex document, and there is evidence that this is partly because the Pope’s thought is given in a version influenced by someone else.” 12

He was apparently unaware of Ratzinger’s role as ghost writer of the document.

Secondly, and even more significantly, Ratzinger’s contrived image of a jolly John XXIII was a pretext to present in a negative light the Church’s “old policy of exclusiveness, condemnation and defence” that he interpreted as “leading to an almost neurotic denial of all that was new.” 13 It was his way of saying that Vatican II was the “cure” for Tradition.

Continued

Few post-Vatican II conservative-leaning Catholics realize that Fr. Joseph Ratzinger, in collaboration with Fr. Karl Rahner, was the main theologian in the opening months of the Council who rejected most of the initial draft documents, and who demanded that they be reworked to suit modern sensibilities. It is important to keep in mind that these official drafts, prepared by the Central Preparatory Commission under the direction of Card. Ottaviani, were based on the authentic Catholic doctrines taught by pre-Vatican II Popes, which crucially, represented the theological content of the seminary text-books or Manuals.

Rahner & Ratzinger collaborated to undermine

the perennial Catholic doctrine

“[Modern disbelief] cannot be countered by merely sticking to the precious metal of the fixed formulas of days gone by, for then it remains just a lump of metal, a burden instead of something offering by virtue of its value the possibility of true freedom. This is where the present book comes in: its aim is to help understand faith afresh as something that makes possible true humanity in the world of today, to expound faith without changing it into the small coin of empty talk painfully laboring to hide a complete spiritual vacuum.” 1

As he mentioned in the Preface, the content of his book was taken from a lecture he gave in 1967 to students at the University of Tübingen. Paradoxically, he seems to have considered that his role as Professor was to teach them to despise the “Manualist tradition.” For that is the inevitable outcome of denouncing as a now useless anachronism the Church’s revered (and highly successful) Scholastic method of teaching the Faith with Manuals.

Ratzinger’s complicity with radical revolution

Prof. Ratzinger’s 1967 lecture could not have come at a worse time. West Germany was at the centre of the European student protest movement of 1968, and was led by the Socialist student activist, Rudi Dutschke. (It was he, incidentally, who formulated the term, “Long March through the Institutions” as a strategy for working against established structures while working within them).

Many students at the University of Tübingen, where Ratzinger had been teaching for two years, were among those who took an active part in the ensuing widespread riots, violence and destruction. Their rebellion was essentially a protest against all “fixed formulas” (as found, for instance, in Humanae vitae which was a particular flashpoint) that supported patriarchal structures, lifestyle patterns and traditional morals operating in the Church and society.

As with similar lectures by his contemporaries, Fr. Karl Rahner and Fr. Hans Küng, Prof. Ratzinger’s were packed with hundreds of radicalized students attracted like bees to a honey pot. (In later life, he put a euphemistic gloss on his popularity with the students by saying that they “reacted enthusiastically to the new tone they thought they heard in my words.”) 2

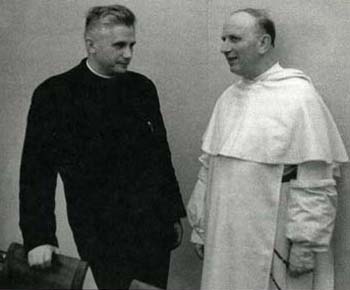

Fr. Ratzinger & Card. Frings listen to Hans Maier,

Bavarian Minister of Education

Ratzinger’s determination to rid the Church of “fixed formulas” ‒ which had acted as the glue that helped keep the Christian order of Church and society from dissolution ‒ did nothing to improve the situation, and even helped to fan the flames of revolt. With so much pressure from all sides for “emancipation,” the University descended into a maelstrom of revolution and radical theology, and the Church itself followed suit, fracturing in the process its common bonds of tradition, custom, culture and morality.

This parlous situation can be seen as an early stage of the abdication of clerical authority that would become evident after Vatican II when bishops and priests simply gave up the fight for the interests of the Church against revolutionary forces that sought to destroy her. There can be no doubt that keeping the “Manualist tradition” with its “fixed formulas” would have been a sure bulwark against the revolution.

Mid-20th century crisis of the 'Manualist tradition' in seminaries

Referring to his own seminary days, Ratzinger commented with obvious relish:

“All of us lived with a feeling of radical change that had already arisen in the 1920s, the sense of a theology that had the courage to ask new questions and a spirituality that was doing away with what was dusty and obsolete and leading to a new joy in the redemption.” 4

His opinion that “courage” was needed to ask new theological questions in the early 20th century was a veiled critique of the Roman authorities who were attempting to crush the Modernist movement. He did not distinguish between questioning as enquiry (as in “faith seeking understanding”) and questioning as implying either doubt or outright incredulity (as in Modernism’s scepticism towards accepted doctrine). And yet the distinction is crucial, for right understanding and effective communication of ideas always involve making careful distinctions, as he would have found in the Manuals, had he consulted them.

The point of Ratzinger’s opinion was obviously to reinforce the usual progressivist stereotype of the pre-Vatican II Church as a hidebound, obscurantist institution propping up a tyrannical regime that suppresses progress by stifling intellectual enquiry and debate. What he failed to appreciate was that the Scholastic method of explaining the Faith does not require people to refrain from asking questions; but it does prevent them from arriving at wrong answers in the sense of drawing conclusions from initial premises that are contrary to Catholic principles.

In fact, the value and legitimacy of asking questions were always recognized in the Church. St. Thomas’s Summa, for instance, was constructed on that method: it contains as many questions as there are answers. Then there were the great Disputationes and Controversiae of the Counter-Reformation period which were dedicated to solving quaestiones about theological matters. These gave rise to much intellectual ferment and debate, all of which was subsumed in the Scholastic system, eventually emerging in the “Manualist tradition.”

The Church, then, never had a problem with asking questions. The problem was with progressivist theologians who did not want to hear the answers.

Ratzinger’s attraction to turn-of-the-century progressivist theology (of the kind dubbed “Modernism” and condemned by Pope Pius X) was a key factor in his dismissal of “fixed formulas” found in the dusty old tomes of the “Manualist tradition.” Like his fellow neo-modernists, he was intoxicated by the prospect of the exciting new developments in theology that would open new horizons for him and satisfy his thirst for novelty. The leading progressivist theologian of Pius XII’s time, Henri de Lubac SJ, attained hero status in his eyes: he, too, scorned the Scholastic tradition found in the Manuals.

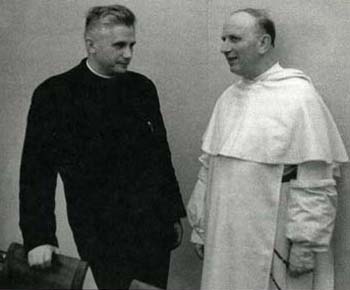

Ratzinger with the no less radical Yves Congar

In addition to these French sources, Ratzinger adds in his Memoirs a Pléiade of contemporary German progressivist theologians 5 who exerted a fundamental influence on his thinking. These included his professor of Moral Theology, Fr, Richard Egenter and his colleagues who were seeking “to end the dominance of casuistry and the Natural Law” and would allow people to “to rethink morality on the basis of the following of Christ.” 6

Unsurprisingly, they all rejected the “Manualist tradition.” The Bible, rather than Tradition, would be the guiding rule. This is enough to show that Ratzinger belonged to a bohemian fringe of theologians who rallied against mainstream theology and challenged dominant values in the Church.

The inescapable conclusion is that Ratzinger was on the side of the neo-modernists who want unlimited academic freedom rather than submit their intellects to the authority of the Hierarchy in matters of revealed doctrine. This is confirmed by his observation that, at the beginning of the Council, Pope John XXIII “by the force of his personality” had infused the proceedings with a “holy freedom” and a new spirit of “openness and candor.” He saw this turn-around as a catharsis in the sense that “the anti-modernistic neurosis that had again and again crippled the Church since the turn of the century here seemed to be approaching a cure.” 7

Fr. Ratzinger, the personal secretary of Card. Frings

According to Frings’s biographer, Fr. Norbert Trippen, John XXIII was so pleased with its contents and tone that he declared it to be entirely compatible with his own intentions for the Council. 10 Anyone who reads the Lecture (a translation of selected passages into English is also available) 11 can see an exact correspondence at several points with the text of John XXXIII’s Opening Speech, Gaudet Mater Ecclesia. Interestingly, Romano Amerio who was a peritus at the Council, detected the hand of a hidden author:

“The opening speech of the Council … is a complex document, and there is evidence that this is partly because the Pope’s thought is given in a version influenced by someone else.” 12

He was apparently unaware of Ratzinger’s role as ghost writer of the document.

Secondly, and even more significantly, Ratzinger’s contrived image of a jolly John XXIII was a pretext to present in a negative light the Church’s “old policy of exclusiveness, condemnation and defence” that he interpreted as “leading to an almost neurotic denial of all that was new.” 13 It was his way of saying that Vatican II was the “cure” for Tradition.

Continued

- Joseph Ratzinger, Introduction to Christianity, (original title Einführung in das Christentum) trans. J. R. Foster, Herder and Herder, 1970, pp. 11-12.

- Benedict XVI with Peter Seewald, Last Testament: In His Own Words, Bloomsbury Publishing, 2016, p. 108.

- The subject of clerical patronage of the1968 student protest movement in Germany is well documented by Christian Schmidtmann, Katholische Studierende 1945-1973: Ein Beitrag zur Kultur und Sozialgeschichte der Bundesrepublik Deutschland (Catholic Students 1945-1973: A Contribution to the Cultural and Social History of the Federal Republic of Germany), Paderborn: Ferdinand Schöningh, 2005, pp. 280-282.

- Joseph Ratzinger, Milestones: Memoirs 1927-1977, trans. Erasmo Leiva-Merikakis, San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 1998, p. 57.

- Ibid., pp. 49, 55; notably Frs. Richard Egenter, Michael Schmaus, Gottlieb Söhngen, Josef Pascher, Fritz Tillman, Theodor Steinbüchel, and Friedrich Wilhelm Maier.

- Ibid., p. 55.

- J. Ratzinger, Theological Highlights of Vatican II, trans. Henry Traub, Gerard Thormann, and Werner Barzel, New York: Paulist Press, 1966, p. 11.

- Benedict XVI with Peter Seewald, Last Testament, p. 130.

- ‘Kardinal Frings über das Konzil und die moderne Gedankenwelt’ (Cardinal Frings on the Council and the Modern World of Thought), Herder-Korrespondenz, vol. 16, 1961/62, pp. 168-174.

- Norbert Trippen, Josef Kardinal Frings (1887-1978): Sein Wirken Für Die Weltkirche Und Seine Letzten Bischofsjahre (His Work for the Universal Church and his Final Episcopal Years), 2 vol., vol. 2, Paderborn: Ferdinand Schöningh, 2005, p. 262.

- Jared Wicks, SJ, ‘Six texts by Prof. Joseph Ratzinger as peritus before and during Vatican Council II,’ Gregorianum, vol. 89, no. 2, 2008, pp. 254-261.

- Romano Amerio, Iota Unum: A Study of Changes in the Catholic Church in the Twentieth Century, Angelus Press, 1996, p. 73.

- J. Ratzinger, Theological Highlights of Vatican II, p. 23.

Posted April 8, 2024

______________________

______________________

Volume I |

Volume II |

Volume III |

Volume IV |

Volume V |

Volume VI |

Volume VII |

Volume VIII |

Volume IX |

Volume X |

Volume XI |

Special Edition |