Traditionalist Issues

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Dialogue Mass - LXXIV

‘Active Participation’ Revisited

We began this study with the theme of “active participation” (actuosa participatio in Latin). As a catch-phrase, it rose to prominence in the Church within the Liturgical Movement in the mid 20th century, having sprung fully formed from the new “theology of the liturgical assembly,” like Venus from the sea, and soon gave rise to its own mythology.

Before that, it was customary to describe the faithful as “assisting at Mass” (understood as “being present” at the Holy Sacrifice), “hearing Mass” in silence while the priest “said” the Mass, or “receiving the Sacraments” at the hands of the priest. There was no question of the laity having the responsibility of actively “celebrating” these ceremonies along with the priest.

Before that, it was customary to describe the faithful as “assisting at Mass” (understood as “being present” at the Holy Sacrifice), “hearing Mass” in silence while the priest “said” the Mass, or “receiving the Sacraments” at the hands of the priest. There was no question of the laity having the responsibility of actively “celebrating” these ceremonies along with the priest.

That was something entirely new in the Church.

It was only when Vatican II’s Liturgy Constitution promoted “active participation” as the primary goal of the liturgy (“the aim to be achieved before all else”) (1) that this hitherto relatively unknown quantity ricocheted around the world. Even before the invention of the internet, within a short time it achieved viral status.

The expression was on the lips of liturgical reformers throughout the Church, soon becoming etched into the collective imagination as the defining characteristic of the reform. The infatuation with “active participation” proved itself to be boundless. No aspect of the liturgy was immune to its influence, for all the reforms, including those of Pius XII, were specifically devised with the “active participation” of the faithful in mind. One could say that the Vatican II liturgical reform has “active participation” running through it like the letters in a stick of rock. (2)

It is now time to recapitulate the main points of this new principle which revolutionized the whole of liturgical life. We will be addressing the following questions:

It says something about the standards of reliability in the Liturgical Movement that everyone took it for granted that “actuosa participatio” came from the pen of Pius X, without making any serious effort to investigate the truth of the claim. Such insouciance about the authenticity of provenance would not be considered acceptable in the world of fine arts, archaeology, commerce, scientific experiments and many other areas of public life. For, provenance is the determining factor in distinguishing between what is genuine and what is fake, and in deciding what information is to be trusted.

Who would give a large sum of money to a dodgy dealer in the antiquities market for an artefact with no identifiable origin? So, why should we entrust the infinitely greater value of our souls to the machinations of liturgical progressivists when many of their ideas have been exposed by modern researchers as based on fiction?

Who would give a large sum of money to a dodgy dealer in the antiquities market for an artefact with no identifiable origin? So, why should we entrust the infinitely greater value of our souls to the machinations of liturgical progressivists when many of their ideas have been exposed by modern researchers as based on fiction?

As for the expression “active participation,” when we consider the question of the authenticity of its provenance, we touch on the moral issue of the reform which includes honesty and integrity. Did Pius X actually use the word actuosa (active) or did he not?

True, the Italian version of Pius X’s 1903 motu proprio contained the word attiva (active) in connection with lay participation in the liturgy. Nevertheless, the only authentic and authoritative document that faithfully reproduces his words is the Latin version, and an attentive reading of that document would show that the word actuosa is entirely missing.

Like the dog in the Sherlock Holmes story (3) who didn’t bark in the night, it is the absence of the epithet actuosa that clinches the argument against the notion that Pius X intended lay people to perform parts of the liturgy. No further evidence is needed to disprove the claim that Pius X used actuosa in his Latin document.

This is not an insignificant discrepancy between the two documents, for the equivalent of the word “active” in the Italian version would determine the outcome of the whole liturgical reform, whereas the Latin version simply preserved and fostered Tradition. In fact, actuosa participatio was the dominant theme of the reform movement under Pius XII – it made its first appearance in his time – and also colored the outlook of many Bishops and priests of the pre-Vatican II generation. It influenced the creation of the Novus Ordo Mass in which the priest was reduced to being the “presider” over the rest of the assembly’s activities.

Given that the “active” element was the guiding principle of the reform, it is highly implausible that the writer of the Latin version “forgot” to include actuosa or thought it was to be simply taken for granted. It was not there because it was not meant to be there. And it was not meant to be there because it does not “fit” with the traditional lex orandi, being incompatible with the values and culture of Catholic worship.

Contextual evidence

Let it not be thought that evidence of absence alone is the only argument being adduced. Another factor that is equally important, if not more so, is the contextual evidence of the document. We have seen how the phrase “active participation” did not derive from the Latin text itself, but nevertheless managed to serve the revolutionary agenda of the reformers. It has also been demonstrated that no part of the original Latin document indicates that the Pope envisaged an “active” role for the congregation. See here and here.

In the wider context, Pius X had never mentioned “active participation” in any document he wrote on Sacred Music before he became Pope – nor did his predecessor, Pope Leo XIII. Indeed, such a concept was never mentioned in any previous papal document going back in history to the earliest centuries.

In the wider context, Pius X had never mentioned “active participation” in any document he wrote on Sacred Music before he became Pope – nor did his predecessor, Pope Leo XIII. Indeed, such a concept was never mentioned in any previous papal document going back in history to the earliest centuries.

There is simply no convincing evidence that Pius X intended the congregation to participate by singing Gregorian Chant, for in his motu proprio he stated that “singers in church have a real liturgical office.” Therefore, he designated the clergy and the all-male choir as the sole legitimate executors of Gregorian Chant. We may infer that the congregation was, by definition, not included in this form of participation.

It is clear, then, that Pius X regarded the laity as listeners, not singers. This is reinforced in another part of the same document where he mentioned two distinct categories of participants in the liturgy: those who sing (the clergy and the choir) and those for whose spiritual benefit the singing is undertaken (the rest of the faithful).

This makes perfect sense only in terms of traditional Catholic worship, as it is the clergy who communicate the divine to the faithful by the performance of the rites. (Conversely, it would make no sense at all to claim that the congregation has a right and a duty to perform the singing along with the clergy and the choir).

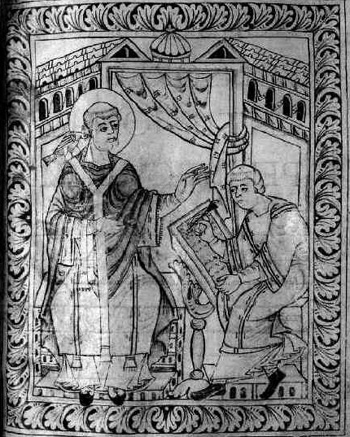

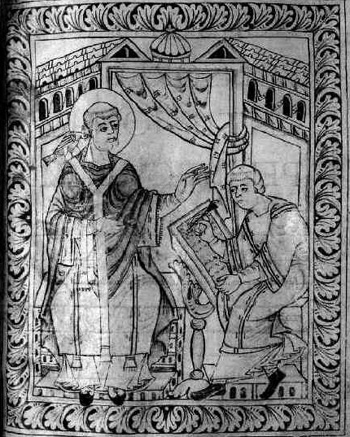

Catholic Tradition has preserved the idea that Gregorian Chant is of divine inspiration and is a means of grace for the faithful. In medieval iconography, Pope Gregory the Great is often depicted with a dove, representing the Holy Spirit, whispering the melodies into his ear as he composed them, while a scribe writes them down.

In § 2 of the General Principles, Pius X referred first to the holiness of Gregorian Chant and the “manner in which it is presented by those who execute it.” Then, he mentioned the efficacy of such music in touching the hearts and minds of those who listen to it (“in animis audientium illam”).

In § 2 of the General Principles, Pius X referred first to the holiness of Gregorian Chant and the “manner in which it is presented by those who execute it.” Then, he mentioned the efficacy of such music in touching the hearts and minds of those who listen to it (“in animis audientium illam”).

But, in order to produce the desired effect of helping the soul to attain deeper levels of contemplation of the divine mysteries, the singing must “semper optime canatur” (always be sung to the highest standards (4)), and the voices competently trained for that purpose.

That is why Pius X called for Scholae Cantorum to be established in seminaries and religious institutions “for the execution of sacred polyphony and of good liturgical music” (§ 25), and also at parochial level, “even in smaller churches and country parishes.” (§ 27)

Moreover, it is inconceivable that this great anti-Modernist Pope and defender of the priesthood would have officially endorsed an active role for the congregation in the liturgy. As we have seen, this grew out of the subversive claim, espoused by progressivist theologians who were the heirs of the modernists condemned by Pius X, that the laity had both the right and duty to perform parts of the liturgy with the priest.

It was part and parcel of the new “theology of the assembly,” which was not really new because it simply recapitulated old “Reformation” heresies condemned by the Council of Trent and were making a comeback after Pius X had driven the modernists underground.

What is perturbing about this situation is that an expression whose impact was felt throughout the Church has no properly authenticated origin.

Continued

'Active participation' rises fully formed in the Church like another Venus from the sea...

That was something entirely new in the Church.

It was only when Vatican II’s Liturgy Constitution promoted “active participation” as the primary goal of the liturgy (“the aim to be achieved before all else”) (1) that this hitherto relatively unknown quantity ricocheted around the world. Even before the invention of the internet, within a short time it achieved viral status.

The expression was on the lips of liturgical reformers throughout the Church, soon becoming etched into the collective imagination as the defining characteristic of the reform. The infatuation with “active participation” proved itself to be boundless. No aspect of the liturgy was immune to its influence, for all the reforms, including those of Pius XII, were specifically devised with the “active participation” of the faithful in mind. One could say that the Vatican II liturgical reform has “active participation” running through it like the letters in a stick of rock. (2)

It is now time to recapitulate the main points of this new principle which revolutionized the whole of liturgical life. We will be addressing the following questions:

- Where did the expression come from?

- What was its precise meaning?

- Was it really necessary?

- How was it received by the laity?

- What effects did it produce?

It says something about the standards of reliability in the Liturgical Movement that everyone took it for granted that “actuosa participatio” came from the pen of Pius X, without making any serious effort to investigate the truth of the claim. Such insouciance about the authenticity of provenance would not be considered acceptable in the world of fine arts, archaeology, commerce, scientific experiments and many other areas of public life. For, provenance is the determining factor in distinguishing between what is genuine and what is fake, and in deciding what information is to be trusted.

The original Latin document of the Saint never used the word actuosa (active)

As for the expression “active participation,” when we consider the question of the authenticity of its provenance, we touch on the moral issue of the reform which includes honesty and integrity. Did Pius X actually use the word actuosa (active) or did he not?

True, the Italian version of Pius X’s 1903 motu proprio contained the word attiva (active) in connection with lay participation in the liturgy. Nevertheless, the only authentic and authoritative document that faithfully reproduces his words is the Latin version, and an attentive reading of that document would show that the word actuosa is entirely missing.

Like the dog in the Sherlock Holmes story (3) who didn’t bark in the night, it is the absence of the epithet actuosa that clinches the argument against the notion that Pius X intended lay people to perform parts of the liturgy. No further evidence is needed to disprove the claim that Pius X used actuosa in his Latin document.

This is not an insignificant discrepancy between the two documents, for the equivalent of the word “active” in the Italian version would determine the outcome of the whole liturgical reform, whereas the Latin version simply preserved and fostered Tradition. In fact, actuosa participatio was the dominant theme of the reform movement under Pius XII – it made its first appearance in his time – and also colored the outlook of many Bishops and priests of the pre-Vatican II generation. It influenced the creation of the Novus Ordo Mass in which the priest was reduced to being the “presider” over the rest of the assembly’s activities.

Given that the “active” element was the guiding principle of the reform, it is highly implausible that the writer of the Latin version “forgot” to include actuosa or thought it was to be simply taken for granted. It was not there because it was not meant to be there. And it was not meant to be there because it does not “fit” with the traditional lex orandi, being incompatible with the values and culture of Catholic worship.

Contextual evidence

Let it not be thought that evidence of absence alone is the only argument being adduced. Another factor that is equally important, if not more so, is the contextual evidence of the document. We have seen how the phrase “active participation” did not derive from the Latin text itself, but nevertheless managed to serve the revolutionary agenda of the reformers. It has also been demonstrated that no part of the original Latin document indicates that the Pope envisaged an “active” role for the congregation. See here and here.

Pope Pius X specified he wanted all male, well-trained Scholae for every parish

There is simply no convincing evidence that Pius X intended the congregation to participate by singing Gregorian Chant, for in his motu proprio he stated that “singers in church have a real liturgical office.” Therefore, he designated the clergy and the all-male choir as the sole legitimate executors of Gregorian Chant. We may infer that the congregation was, by definition, not included in this form of participation.

It is clear, then, that Pius X regarded the laity as listeners, not singers. This is reinforced in another part of the same document where he mentioned two distinct categories of participants in the liturgy: those who sing (the clergy and the choir) and those for whose spiritual benefit the singing is undertaken (the rest of the faithful).

This makes perfect sense only in terms of traditional Catholic worship, as it is the clergy who communicate the divine to the faithful by the performance of the rites. (Conversely, it would make no sense at all to claim that the congregation has a right and a duty to perform the singing along with the clergy and the choir).

Catholic Tradition has preserved the idea that Gregorian Chant is of divine inspiration and is a means of grace for the faithful. In medieval iconography, Pope Gregory the Great is often depicted with a dove, representing the Holy Spirit, whispering the melodies into his ear as he composed them, while a scribe writes them down.

St. Gregory the Great dictates to a scribe melodies sung to him by a dove, representing the Holy Spirit

But, in order to produce the desired effect of helping the soul to attain deeper levels of contemplation of the divine mysteries, the singing must “semper optime canatur” (always be sung to the highest standards (4)), and the voices competently trained for that purpose.

That is why Pius X called for Scholae Cantorum to be established in seminaries and religious institutions “for the execution of sacred polyphony and of good liturgical music” (§ 25), and also at parochial level, “even in smaller churches and country parishes.” (§ 27)

Moreover, it is inconceivable that this great anti-Modernist Pope and defender of the priesthood would have officially endorsed an active role for the congregation in the liturgy. As we have seen, this grew out of the subversive claim, espoused by progressivist theologians who were the heirs of the modernists condemned by Pius X, that the laity had both the right and duty to perform parts of the liturgy with the priest.

It was part and parcel of the new “theology of the assembly,” which was not really new because it simply recapitulated old “Reformation” heresies condemned by the Council of Trent and were making a comeback after Pius X had driven the modernists underground.

What is perturbing about this situation is that an expression whose impact was felt throughout the Church has no properly authenticated origin.

Continued

- Sacrosanctum Concilium § 14.

- A “stick of rock” is a familiar expression to British people and is associated with seaside resorts, such as Blackpool, Brighton etc. It is a long cylindrical piece of confectionery, usually peppermint flavour, with the name of the town stamped internally throughout its length. In Graham Greene’s novel, Brighton Rock, the character, Ida, says: “It’s like those sticks of rock: bite it all the way down, you'll still read Brighton.”

- The Adventure of Silver Blaze, a story by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, in which Holmes investigates the disappearance of the eponymous racehorse and the apparent murder of its trainer. Holmes grasped the significance of the guard dog’s silence, for the midnight visitor was one the dog knew well. And, as he explained, “one true inference invariably suggests others,” he soon unravelled the mystery.

- The self-styled “official” Italian version in the Acta Sanctae Sedis says “sempre bene eseguite” (always well sung), but bene (well) does not accurately translate the superlative adverb optime (to the highest degree) in the Latin version. We have already pointed out several mistranslations in the Italian version.

Posted August 6, 2018

______________________

______________________

Volume I |

Volume II |

Volume III |

Volume IV |

Volume V |

Volume VI |

Volume VII |

Volume VIII |

Volume IX |

Volume X |

Volume XI |

Special Edition |