Traditionalist Issues

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Dialogue Mass - LXI

Introducing Confusion into the

Symbolism of Baptism

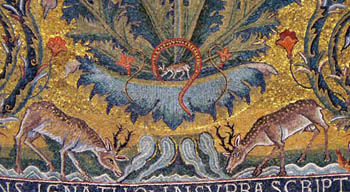

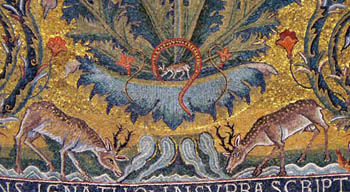

In the pre-1956 liturgy, the blessing of the baptismal water took place in the baptistery, the part of the church (or even a separate building) where the font was traditionally located. The clergy would process from the sanctuary to bless both the font and the water it contained, while the choir chanted the relevant section of Psalm 41, Sicut cervus.

As with the Paschal Candle, this procession was also a clear and shining example of theology in motion. Those who approach the font are compared to the hart in Psalm 41, which yearns for the fountain of living water. It would be useful to keep this visual metaphor in mind when we come to examine the reformed version.

Liturgical havoc

As a result of the invidious schemes drawn up by the 1948 Commission, what happened next put another blot on its already sullied record. True to form, the Commission played havoc with the part of the Easter Vigil liturgy following the reading of the Prophecies, turning what was one of the most ancient and supreme works of Catholic Tradition into what can only be described as a scene of total disorder and confusion.

As we shall see, this section of the Easter Vigil was radically reconfigured, and became a farrago of structural and ritual changes peppered with inconsistencies and quirks.

As we shall see, this section of the Easter Vigil was radically reconfigured, and became a farrago of structural and ritual changes peppered with inconsistencies and quirks.

Instead of blessing the water and administering Baptisms in the designated place where the font is traditionally located, these actions were performed in the sanctuary while the priest faced the people (“coram populo”). This necessitated the use of a bucket or other receptacle for the baptismal water while the font, which had been in continuous use for 16 centuries, was suddenly made redundant and its symbolic importance consequently diminished.

Mgr. Léon Gromier pointed out at the time the effects of dislocating the symbolism of the font from its liturgical context:

“Baptismal fonts, baptismal water and Baptism go together as one. A spectacular innovation that deliberately separates them, installing substitutes for the font in the sanctuary and baptising in them, then using this receptacle for transferring the baptismal water to the font is an insult to history, to discipline, to the liturgy and common sense.” (1)

He was vilified by the liturgical establishment for daring to criticize the Holy Week reform. It is richly ironic that he was regarded as having lost his wits, when it was the authors of that reform who appear to have lost their liturgical compass. The revised ceremony of the baptismal water did indeed fly in the face of logic and common sense.

Mismatch between text & ritual

To begin with, it made nonsense of the metaphor of the thirsty deer in Psalm 41 that symbolizes those who approach the font longing for the waters of Baptism. But in the reformed rite this symbolism is rendered incoherent because the Psalm is sung after the blessing of the water and conferral of Baptism, in other words after the deer has slaked his thirst.

To begin with, it made nonsense of the metaphor of the thirsty deer in Psalm 41 that symbolizes those who approach the font longing for the waters of Baptism. But in the reformed rite this symbolism is rendered incoherent because the Psalm is sung after the blessing of the water and conferral of Baptism, in other words after the deer has slaked his thirst.

To add to the confusion, the Psalm is sung while the procession is heading towards a completely dry font whose role in the ceremony is merely functional – to be the receptacle for the remaining contents of the baptismal bucket.

Mismatch between architecture & ritual

Secondly, with the relocation of the ceremony away from font (traditionally placed near the entrance to the parish church), the architectural symbolism of Baptism as the janua Sacramentorum (the gateway to the Sacraments and the beginning of a new life in the Church) was lost.

Confusion between clergy & laity

Thirdly, and worst of all, is the use of the sanctuary as a makeshift baptistery. It was a radical departure from Tradition because it involved the intrusion of lay people (the not-yet-baptized and their sponsors) into the sanctuary, the place set apart for the clergy.

This was arguably worse than the foot-washing ceremony of Holy Thursday, which allowed laymen to enter the sanctuary. For if, in the reformed Easter Vigil, even the unbaptized were given the same privilege as those in Holy Orders - i.e., of entering the sanctuary - the impression is given that Original Sin can safely be ignored as of little consequence. That was, of course, precisely what happened in the Novus Ordo.

A distracting interruption

Fourthly, the progressivist reformers broke the liturgy free from its accepted context and logic in yet another way.

In the pre-1956 rite, the Litany of the Saints was sung integrally after the blessing of the water and the administration of Baptism. But in the reform the Litany, which was deemed to be too long and repetitive, was split in two, with a medley of ceremonies sandwiched between the two parts – the blessing of the water, the administration of Baptism, an entirely novel “Renewal of Baptismal Promises” and the procession to the font.

In the pre-1956 rite, the Litany of the Saints was sung integrally after the blessing of the water and the administration of Baptism. But in the reform the Litany, which was deemed to be too long and repetitive, was split in two, with a medley of ceremonies sandwiched between the two parts – the blessing of the water, the administration of Baptism, an entirely novel “Renewal of Baptismal Promises” and the procession to the font.

The original symbolism was a clear indication that the newly baptized were incorporated into the Communion of Saints. But this connection was lost by the structural ambiguity of the two disjointed fragments of the Litany. When the chanting suddenly stops in mid stream and the scene shifts to “active participation” in the sanctuary, only to be resumed later, it is questionable what exactly is in the forefront of the people’s minds at any given point. One could call this reform a weapon of mass distraction.

From rational order to plain chaos

Before the reform of Holy Week, both architecture and rite had functioned symbiotically as a sort of map that could be “read” to show the hierarchical nature of the Church and the road to Heaven. Liturgically, everything was “in its place” for a good reason – to symbolize the constitution of the Church and the unity of the Faith. A Catholic identity was made manifest.

When the map was modified in 1956 – it would be torn up completely a few years later – confusion as to the basic sense of Catholic order and certitude was bound to set in. The disorderly combination of elements devised by the reformers resulted in identities lost and distinctions blended.

When the map was modified in 1956 – it would be torn up completely a few years later – confusion as to the basic sense of Catholic order and certitude was bound to set in. The disorderly combination of elements devised by the reformers resulted in identities lost and distinctions blended.

Why this shifting of landscapes, this rearranging of the furniture of the church building and even its internal geography?

In an article written straight after the reform, Fr. Antonelli provided the answer in a nutshell: “To bring the faithful back to active and conscious participation” in the liturgy. Echoing the “grand narrative” of the Liturgical Movement, he said that in recent centuries the faithful had become “no more than silent spectators” divorced from the “liturgical action”; this had become exclusively the preserve of the clergy who were separated from the congregation by a “closed sanctuary.” (2)

A toxic innuendo

Fr. Antonelli’s remarks contain underlying assumptions and biases, drawn from the Liturgical Movement, which entail a slow poisoning of the mind against a true appreciation of lay participation. There is no evidence that the laity felt in the least disadvantaged vis-à-vis the clergy at not being allowed to enter the sanctuary. Yet Fr. Antonelli presented the reform as a means of enabling them finally to enjoy the privilege that they had supposedly long been denied by the clerical patriarchy.

It was on the basis of this fabricated pretext that the Commission introduced the idea, which was to revolutionize the whole of liturgical life, that the Church had a duty to redress the injustice done to the laity and change a system that was deemed inimical to them. And it was on that basis that the progresivists were prepared to break with the accepted forms, symbolism and logic of immemorial tradition to craft a new rite for the Easter Vigil and promote a new paradigm, that of “active participation” for the laity.

A symptom of decay

This is incontrovertible evidence that the reformed Easter Vigil was the first act in the tragedy that would be played out in the Novus Ordo reforms. It set in motion a dynamic of discontinuity with Tradition that would prove impossible to stop, not excluding the 1962 Missal.

For, it was the precondition for the reshaping of the entire liturgy that would progressively destroy the Church’s immemorial traditions. No wonder the progressivists were so keen to make a start on it in 1951.

Continued

As with the Paschal Candle, this procession was also a clear and shining example of theology in motion. Those who approach the font are compared to the hart in Psalm 41, which yearns for the fountain of living water. It would be useful to keep this visual metaphor in mind when we come to examine the reformed version.

Liturgical havoc

As a result of the invidious schemes drawn up by the 1948 Commission, what happened next put another blot on its already sullied record. True to form, the Commission played havoc with the part of the Easter Vigil liturgy following the reading of the Prophecies, turning what was one of the most ancient and supreme works of Catholic Tradition into what can only be described as a scene of total disorder and confusion.

The hart seeking the "living waters" is a symbol of man seeking Baptism

Instead of blessing the water and administering Baptisms in the designated place where the font is traditionally located, these actions were performed in the sanctuary while the priest faced the people (“coram populo”). This necessitated the use of a bucket or other receptacle for the baptismal water while the font, which had been in continuous use for 16 centuries, was suddenly made redundant and its symbolic importance consequently diminished.

Mgr. Léon Gromier pointed out at the time the effects of dislocating the symbolism of the font from its liturgical context:

“Baptismal fonts, baptismal water and Baptism go together as one. A spectacular innovation that deliberately separates them, installing substitutes for the font in the sanctuary and baptising in them, then using this receptacle for transferring the baptismal water to the font is an insult to history, to discipline, to the liturgy and common sense.” (1)

He was vilified by the liturgical establishment for daring to criticize the Holy Week reform. It is richly ironic that he was regarded as having lost his wits, when it was the authors of that reform who appear to have lost their liturgical compass. The revised ceremony of the baptismal water did indeed fly in the face of logic and common sense.

Mismatch between text & ritual

A traditional font at the entrance of Sacred Heart Basilica, Notre Dame

To add to the confusion, the Psalm is sung while the procession is heading towards a completely dry font whose role in the ceremony is merely functional – to be the receptacle for the remaining contents of the baptismal bucket.

Mismatch between architecture & ritual

Secondly, with the relocation of the ceremony away from font (traditionally placed near the entrance to the parish church), the architectural symbolism of Baptism as the janua Sacramentorum (the gateway to the Sacraments and the beginning of a new life in the Church) was lost.

Confusion between clergy & laity

Thirdly, and worst of all, is the use of the sanctuary as a makeshift baptistery. It was a radical departure from Tradition because it involved the intrusion of lay people (the not-yet-baptized and their sponsors) into the sanctuary, the place set apart for the clergy.

This was arguably worse than the foot-washing ceremony of Holy Thursday, which allowed laymen to enter the sanctuary. For if, in the reformed Easter Vigil, even the unbaptized were given the same privilege as those in Holy Orders - i.e., of entering the sanctuary - the impression is given that Original Sin can safely be ignored as of little consequence. That was, of course, precisely what happened in the Novus Ordo.

A distracting interruption

Fourthly, the progressivist reformers broke the liturgy free from its accepted context and logic in yet another way.

A baptismal font in the sanctuary of a modern Catholic church

The original symbolism was a clear indication that the newly baptized were incorporated into the Communion of Saints. But this connection was lost by the structural ambiguity of the two disjointed fragments of the Litany. When the chanting suddenly stops in mid stream and the scene shifts to “active participation” in the sanctuary, only to be resumed later, it is questionable what exactly is in the forefront of the people’s minds at any given point. One could call this reform a weapon of mass distraction.

From rational order to plain chaos

Before the reform of Holy Week, both architecture and rite had functioned symbiotically as a sort of map that could be “read” to show the hierarchical nature of the Church and the road to Heaven. Liturgically, everything was “in its place” for a good reason – to symbolize the constitution of the Church and the unity of the Faith. A Catholic identity was made manifest.

A traditional baptismal font at an altar in St. Patrick's Cathedral, New York City

Why this shifting of landscapes, this rearranging of the furniture of the church building and even its internal geography?

In an article written straight after the reform, Fr. Antonelli provided the answer in a nutshell: “To bring the faithful back to active and conscious participation” in the liturgy. Echoing the “grand narrative” of the Liturgical Movement, he said that in recent centuries the faithful had become “no more than silent spectators” divorced from the “liturgical action”; this had become exclusively the preserve of the clergy who were separated from the congregation by a “closed sanctuary.” (2)

A toxic innuendo

Fr. Antonelli’s remarks contain underlying assumptions and biases, drawn from the Liturgical Movement, which entail a slow poisoning of the mind against a true appreciation of lay participation. There is no evidence that the laity felt in the least disadvantaged vis-à-vis the clergy at not being allowed to enter the sanctuary. Yet Fr. Antonelli presented the reform as a means of enabling them finally to enjoy the privilege that they had supposedly long been denied by the clerical patriarchy.

It was on the basis of this fabricated pretext that the Commission introduced the idea, which was to revolutionize the whole of liturgical life, that the Church had a duty to redress the injustice done to the laity and change a system that was deemed inimical to them. And it was on that basis that the progresivists were prepared to break with the accepted forms, symbolism and logic of immemorial tradition to craft a new rite for the Easter Vigil and promote a new paradigm, that of “active participation” for the laity.

A symptom of decay

This is incontrovertible evidence that the reformed Easter Vigil was the first act in the tragedy that would be played out in the Novus Ordo reforms. It set in motion a dynamic of discontinuity with Tradition that would prove impossible to stop, not excluding the 1962 Missal.

For, it was the precondition for the reshaping of the entire liturgy that would progressively destroy the Church’s immemorial traditions. No wonder the progressivists were so keen to make a start on it in 1951.

Continued

- Mgr. Léon Gromier, “The ‘Restored’ Holy Week,” A Conference given in Paris in July 1960, published in Fr. Ferdinand Portal’s magazine, Opus Dei, n. 2, April 1962, Paris, pp. 89-90.

- Ferdinando Antonelli, “The Liturgical Reform of Holy Week, its Importance, Achievements and Perspective,” La Maison-Dieu,n. 47-48, July 1956, p. 230.

Posted November 6, 2017

______________________

______________________

Volume I |

Volume II |

Volume III |

Volume IV |

Volume V |

Volume VI |

Volume VII |

Volume VIII |

Volume IX |

Volume X |

Volume XI |

Special Edition |