Traditionalist Issues

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Dialogue Mass - XXXIX

Fabricated Charges against Chantries

As we saw in the last article, Fr. Josef Jungmann strongly objected to the pre-Vatican II chantry system. Jungmann contended that chantries were part of a “trend to the private and the subjective … since most of them were for private requests and had no public character.” (1)

In this, as in much else, he was mistaken. For, like all Masses, whether celebrated in a monastery, parish church or special chapel, chantry Masses were not private functions even if no one else happened to be present besides the priest and a server. They were performed by a chaplain in his public authority as a priest in the name of the whole Church.

Apart from the theological aspect, it is obvious from a purely secular angle that Jungmann’s assessment was misconceived, and we have to look to the work of modern-day historians for a broader understanding and appreciation of the chantry system. Dr. Simon Roffey, for example, substantiating his conclusion with detailed documentary evidence, proved that “far from being primarily individualist or indeed ‘private’ monuments, chantry chapels were in fact of great relevance to the wider community.” (2)

Apart from the theological aspect, it is obvious from a purely secular angle that Jungmann’s assessment was misconceived, and we have to look to the work of modern-day historians for a broader understanding and appreciation of the chantry system. Dr. Simon Roffey, for example, substantiating his conclusion with detailed documentary evidence, proved that “far from being primarily individualist or indeed ‘private’ monuments, chantry chapels were in fact of great relevance to the wider community.” (2)

Further in his book, the scholar asserts: “Though chantries and chapels were founded and managed by individuals or by specific collectives, they were very much public monuments and an important feature in communal piety …[they] actively promoted inclusivity and communal participation and greatly embellished, enhanced and encouraged parish church religious practice.” (3)

Their public character is placed beyond doubt by Roffey’s analysis of the topographical arrangement of the chantry chapels. He showed how they were freely accessed from public areas of the church, such as the nave or aisles. Even though some were sectioned off by a screen, (4) this was decorated with openwork tracery in a manner that allowed visibility from the nave. The people, therefore, were not excluded, even visually, from being present at Mass.

Denying the benefits of many Masses

In order to bolster his opposition to the multiplication of Masses, Jungmann made use of the medieval theologian, Meister Eckhart, whom he quoted as saying that “neither blessedness nor perfection consist in saying or hearing a lot of Masses.” (5) As he did not, however, give a context or an original reference for this quote, which is certainly incomplete, it cannot be taken at face value. (6)

But, more to the point, Eckhart was hardly an authority on Catholic doctrine; he was brought before the Inquisition in 1326 on the charge of preaching unorthodox doctrines and causing confusion especially among the simple faithful. It is noteworthy that Jungmann failed to mention that 28 of Eckhart’s propositions were condemned ‒ 17 of them as heretical, and 11 savoring of heresy ‒ by Pope John XXII in 1329 in the Bull

In agro Dominico.

But, more to the point, Eckhart was hardly an authority on Catholic doctrine; he was brought before the Inquisition in 1326 on the charge of preaching unorthodox doctrines and causing confusion especially among the simple faithful. It is noteworthy that Jungmann failed to mention that 28 of Eckhart’s propositions were condemned ‒ 17 of them as heretical, and 11 savoring of heresy ‒ by Pope John XXII in 1329 in the Bull

In agro Dominico.

We have it on the authority of St. Thomas Aquinas that “with several Masses, the offering of the sacrifice is multiplied, and, therefore, the effects of the Sacrament and the Sacrifice are also multiplied.” (7)

How spiritually well-served the medieval faithful were can be gauged from the multiplication of Masses in the cathedrals, monasteries and large churches, where several daily Masses were celebrated simultaneously every hour of the morning. This means that, no matter how early or late the faithful arrived, there would always be a Mass in progress for them to attend.

A typical example is Lincoln Cathedral whose surviving records show that in 1531 about 5 Masses per hour were celebrated simultaneously by the chantry priests from 5 a.m. to 11 a.m. (“from the striking of the fifth hour (ab hora quinta signata) to the eleventh”), with each priest saying his own Mass at a designated side altar. (8) That amounts to about 30 Masses per day within the walls of one church.

If we extrapolate from the above figures over the course of a year, the number of Masses would have increased exponentially; and from there in all the Catholic churches over the whole world down to our day, the sum total of graces bestowed on the human race through the Mass would be incalculable.

This pertained in the Church up until the post-Vatican II years (9) when it was replaced by the widespread practice of concelebration, which drastically reduced the numbers of individual Masses said throughout the world and, consequently, the amount of grace available through them to mankind, living and dead.

Jungmann trod in the steps of Luther

But Jungmann and, with him, the members of the Liturgical Movement who were his disciples, eschewed the traditional position:

“Today in the church that is constructed logically for the corporate celebration of Mass by the whole congregation, the side altars disappear and the church is built as a unified space where all eyes are directed to the one altar upon which the sacrifice is corporately offered, the one meal prepared for all.” (10)

Here we can see the original ground plan of our modern church architecture and liturgical practices, which have swept away centuries of ongoing, authentic Catholic Tradition. The idea of eliminating side altars was originally Luther’s, as was the concept of the Mass as a community meal at which all present are meant to eat and drink.

In 1533, Luther published an attack on the Mass and the Priesthood in which he called especially for the abolition of private Masses said at side chapels. (11) In it, he referred derisively to the private Mass said without a congregation as a “Winckelmesse,” literally a whispered Mass-in-a-corner.

We can see how the same anti-Catholic prejudice has resurfaced in the mainstream Church via the Liturgical Movement. According to Jungmann, the custom of the side altar was an “obstacle in the way of a truly corporate divine worship” and was one of the causes alleged by the Pseudo-Reformation because it had led to a sense of loss of the Church as a “community.” (12)

We can see how the same anti-Catholic prejudice has resurfaced in the mainstream Church via the Liturgical Movement. According to Jungmann, the custom of the side altar was an “obstacle in the way of a truly corporate divine worship” and was one of the causes alleged by the Pseudo-Reformation because it had led to a sense of loss of the Church as a “community.” (12)

Thus, Jungmann can be said to have joined the ranks of those condemned by Pope Pius X in 1907 who “feel no horror at following in the footsteps of Luther.” (13)

Scorn of the Low Mass (14)

Jungmann criticized the Low Mass when it was said without people present, but he did the same even when it was attended by large congregations.

First, he found it too elitist: “Only the priest is permitted to enter the sanctuary to offer the sacrifice. He begins from now on to say the prayers of the Canon in a low voice and the altar becomes farther and farther removed from the people into the rear of the apse. In some measure, the idea of a holy people who are as close to God as the priest is, has become lost. The Church begins to be represented chiefly by the clergy. The corporate character of public worship, so meaningful for early Christianity, begins to crumble at its foundations. (15)

The clear implication here is that there is no distinction between the priest and the people in the offering of the Mass, and that the lex orandi, which gave a privileged place to the clergy was unjust and domineering. Consequently, a reform would be needed to restore the “rights” of the laity.

Second, he accused the “silent” Low Mass of being an obstacle to true participation by the laity. In his opinion, it led to “the estrangement of those who attended Mass without really taking part in it,” (16) with the result that “the Mass is looked upon as a holy drama, a play performed before the eyes of the participants.” (17) The expression “dumb spectators” springs to mind.

These complaints raise theological issues about the identity of the Catholic priesthood, at the very heart of which lies the meaning of the Mass. It is that issue which, first, the 16th century Protestants and, then, the 20th century liturgical progressivists aimed to destroy. And the same complaints have been acting ever since as a corrosive acid eating away at our Catholic institutions, values and identity.

Continued

In this, as in much else, he was mistaken. For, like all Masses, whether celebrated in a monastery, parish church or special chapel, chantry Masses were not private functions even if no one else happened to be present besides the priest and a server. They were performed by a chaplain in his public authority as a priest in the name of the whole Church.

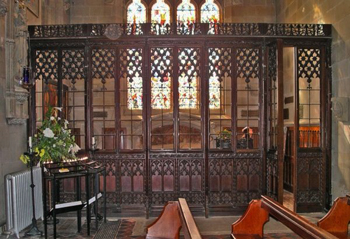

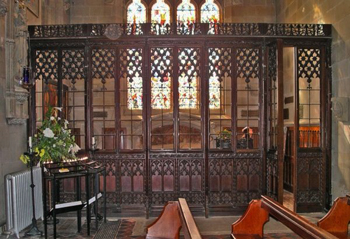

A parclose screen in a chantry chapel, allowing visibility

Further in his book, the scholar asserts: “Though chantries and chapels were founded and managed by individuals or by specific collectives, they were very much public monuments and an important feature in communal piety …[they] actively promoted inclusivity and communal participation and greatly embellished, enhanced and encouraged parish church religious practice.” (3)

Their public character is placed beyond doubt by Roffey’s analysis of the topographical arrangement of the chantry chapels. He showed how they were freely accessed from public areas of the church, such as the nave or aisles. Even though some were sectioned off by a screen, (4) this was decorated with openwork tracery in a manner that allowed visibility from the nave. The people, therefore, were not excluded, even visually, from being present at Mass.

Denying the benefits of many Masses

In order to bolster his opposition to the multiplication of Masses, Jungmann made use of the medieval theologian, Meister Eckhart, whom he quoted as saying that “neither blessedness nor perfection consist in saying or hearing a lot of Masses.” (5) As he did not, however, give a context or an original reference for this quote, which is certainly incomplete, it cannot be taken at face value. (6)

Meister Eckhart, 28 propositions condemned as heretical or with flavor of heresy

We have it on the authority of St. Thomas Aquinas that “with several Masses, the offering of the sacrifice is multiplied, and, therefore, the effects of the Sacrament and the Sacrifice are also multiplied.” (7)

How spiritually well-served the medieval faithful were can be gauged from the multiplication of Masses in the cathedrals, monasteries and large churches, where several daily Masses were celebrated simultaneously every hour of the morning. This means that, no matter how early or late the faithful arrived, there would always be a Mass in progress for them to attend.

A typical example is Lincoln Cathedral whose surviving records show that in 1531 about 5 Masses per hour were celebrated simultaneously by the chantry priests from 5 a.m. to 11 a.m. (“from the striking of the fifth hour (ab hora quinta signata) to the eleventh”), with each priest saying his own Mass at a designated side altar. (8) That amounts to about 30 Masses per day within the walls of one church.

If we extrapolate from the above figures over the course of a year, the number of Masses would have increased exponentially; and from there in all the Catholic churches over the whole world down to our day, the sum total of graces bestowed on the human race through the Mass would be incalculable.

This pertained in the Church up until the post-Vatican II years (9) when it was replaced by the widespread practice of concelebration, which drastically reduced the numbers of individual Masses said throughout the world and, consequently, the amount of grace available through them to mankind, living and dead.

Jungmann trod in the steps of Luther

But Jungmann and, with him, the members of the Liturgical Movement who were his disciples, eschewed the traditional position:

“Today in the church that is constructed logically for the corporate celebration of Mass by the whole congregation, the side altars disappear and the church is built as a unified space where all eyes are directed to the one altar upon which the sacrifice is corporately offered, the one meal prepared for all.” (10)

Here we can see the original ground plan of our modern church architecture and liturgical practices, which have swept away centuries of ongoing, authentic Catholic Tradition. The idea of eliminating side altars was originally Luther’s, as was the concept of the Mass as a community meal at which all present are meant to eat and drink.

In 1533, Luther published an attack on the Mass and the Priesthood in which he called especially for the abolition of private Masses said at side chapels. (11) In it, he referred derisively to the private Mass said without a congregation as a “Winckelmesse,” literally a whispered Mass-in-a-corner.

Multiple Masses said at side chapels eliminated, replaced by concelebration, below

Thus, Jungmann can be said to have joined the ranks of those condemned by Pope Pius X in 1907 who “feel no horror at following in the footsteps of Luther.” (13)

Scorn of the Low Mass (14)

Jungmann criticized the Low Mass when it was said without people present, but he did the same even when it was attended by large congregations.

First, he found it too elitist: “Only the priest is permitted to enter the sanctuary to offer the sacrifice. He begins from now on to say the prayers of the Canon in a low voice and the altar becomes farther and farther removed from the people into the rear of the apse. In some measure, the idea of a holy people who are as close to God as the priest is, has become lost. The Church begins to be represented chiefly by the clergy. The corporate character of public worship, so meaningful for early Christianity, begins to crumble at its foundations. (15)

The clear implication here is that there is no distinction between the priest and the people in the offering of the Mass, and that the lex orandi, which gave a privileged place to the clergy was unjust and domineering. Consequently, a reform would be needed to restore the “rights” of the laity.

Second, he accused the “silent” Low Mass of being an obstacle to true participation by the laity. In his opinion, it led to “the estrangement of those who attended Mass without really taking part in it,” (16) with the result that “the Mass is looked upon as a holy drama, a play performed before the eyes of the participants.” (17) The expression “dumb spectators” springs to mind.

These complaints raise theological issues about the identity of the Catholic priesthood, at the very heart of which lies the meaning of the Mass. It is that issue which, first, the 16th century Protestants and, then, the 20th century liturgical progressivists aimed to destroy. And the same complaints have been acting ever since as a corrosive acid eating away at our Catholic institutions, values and identity.

Continued

- Josef Jungmann, Mass of the Roman Rite, vol. 1, p. 131. Jungmann defined the private Mass as “a Mass celebrated for its own sake, with no thought of anyone participating, a Mass where only the prescribed server is in attendance or even where no one is present, as was the case with the missa solitaria”. (Ibid. p. 215)

- Simon Roffey, The Medieval Chantry Chapel: An Archaeology, Boydell Press, 2007, p. 6.

- Ibid. pp. 160-161.

- In architectural terms, this was called a parclose screen and was often intricately carved with fine trellis work, leaving plenty of open spaces for visibility from the main body of the church.

- J. Jungmann, Mass of the Roman Rite, vol. 1, p. 131, note 25. Johannes Eckhart (c. 1260-c. 1328), popularly known as Meister Eckhart, was a German Dominican theologian, preacher and mystic. He was well known for criticizing “Pharisaical” external actions not performed with the right inner disposition, i.e. out of love of God. It seems that this essential condition for gaining merit from the performance of good works (such as saying or hearing Mass) was missing from Jungmann’s quote.

- We are not given direct access to the original quote attributed to Meister Eckhart. Jungmann reproduced it from Adolph Franz, who in turn took it from a 19th century historian, Anton Linsenmayer, Geschichte der Predigt in Deutschland (History of Preaching in Germany). (Munich, 1886, p. 408) It is evident that Jungmann suppressed the context that Franz had given, namely Eckhart’s insistence that outward observance alone is insufficient: “alle äusseren Übungen nicht Selbstzweck, sondern nur Mittel zur Erreichung des höchsten Zieles, der Vereinigung mit Gott durch Jesus Christus, seien.” (all outer exercises are not ends in themselves, but a means to achieve the highest goal, the union with God through Jesus Christ) See A. Franz, Die Messe im Deutschen Mittelalter (The Mass in Medieval Germany), Freiburg, Herder, 1902, p. 298.

- St. Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologica, Part III, q. 79, a. 7, ad. 3.

- R.E.G. Cole (ed.), Chapter Acts of the Cathedral Church of St Mary of Lincoln A.D. 1520-1536 , Publications of the Lincoln Record Society, 1915, pp. 142-144. These records show that, in addition, there was Mass at the altar of the Blessed Virgin Mary, High Mass at the main altar at 11 a.m. and another chantry Mass at a side altar later in the morning.

- Pre-Vatican II Catholics will recall that in any large town or city where there was a cathedral, monastery or house of a religious order of priests, Masses were available throughout the morning starting from about 5 a.m., and that they were generally well attended by people on their way to work, by mothers who had taken their children to school, by the retired and elderly and by passing visitors.

- J. Jungmann, Announcing the Word of God, translated from the German by Ronald Walls, London: Burns and Oates, 1967, p. 118.

- Martin Luther, Von der Winckelmesse und Pfaffen Weihe (Of the Corner Mass and Ordained Priests), Wittenberg: Nickel Schirlentz, 1533. The first few pages of the book take the form of a dialogue which Luther stated he had with the Devil. In it, according to Luther, the Devil persuaded him to give up saying Mass on the grounds that it was an idolatrous service. But the illogicality of calling the Mass a form of idolatry did not strike Luther. As idolatry is Devil’s worship, why should Satan recommend abolishing it? And, as Prince of this world, why should he want to destroy his own Empire? It was Scripture, not Satan, which condemned idolatry: “Wherefore, my dearly beloved, flee from idolatry.” (1 Corinthians 10:14)

- J. Jungmann, “The Defeat of Teutonic Arianism and the Revolution of Religious Culture in the Early Middle Ages,” Pastoral Liturgy, New York: Herder and Herder, 1962, pp. 68, 79. Jungmann’s essay was originally written in 1947 and was reproduced in Pastoral Liturgy, 1962.

- Pius X, Pascendi, 1907, § 18.

- The Low Mass was sometimes referred to as Missa Privata, but the word privata (Latin for “deprived”) simply meant that this form of Mass, while still retaining its sense of mystery and its quintessentially Catholic nature, lacked certain ceremonies found in the High Mass. In the rubrics of the Low Mass, everything is recited by the priest and the responses are made by the server; there is no role for the deacon, sub-deacon or choir; incense is not used and there are only two candles. Under the influence of the Liturgical Movement, the silent lay people attending at Mass were encouraged to speak aloud and sing the responses at Low Mass well before Vatican II.

- J. Jungmann, “The Defeat of Teutonic Arianism and the Revolution of Religious Culture in the Early Middle Ages,” p. 60.

- J. Jungmann, Mass of the Roman Rite, vol. 1, p. 141.

- Ibid., p. 107.

Posted October 5, 2016

______________________

______________________

Volume I |

Volume II |

Volume III |

Volume IV |

Volume V |

Volume VI |

Volume VII |

Volume VIII |

Volume IX |

Volume X |

Volume XI |

Special Edition |