Traditionalist Issues

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Dialogue Mass - XXVI

Denying the Sacrificial Character of the Mass

Jungmann’s history of the Mass raises questions in the enquiring reader’s mind: Why should he have spent a decade of painstaking and meticulous research to produce a work that disparaged the faith and practice of virtually the entire history of the Church’s liturgy? What was Jungmann trying to achieve?

His concern was to amass “evidence” to show that, soon after the early years of Christianity, the Church’s liturgy had become “doctrinally corrupt” in its theology of the Mass and the priesthood. His magnum opus was an endeavor of large proportions. It was as if he had set out to bury the Roman Rite under a complex web of falsehoods and was building an elaborate funerary monument or vast mortuary palace to commemorate its passing.

But, of course, he did not succeed, no more than had the Protestants of the Pseudo-Reformation who embarked on the same quest. For the traditional Mass has unfailingly confirmed throughout the ages the Faith of the Apostles in the true meaning of the Holy Sacrifice, the Real Presence and their own priesthood.

A front for Neo-Modernism

Where Jungmann did, however, achieve success was in influencing Church leaders and policy makers to accept his progressivist or neo-modernist ideas.

His work is a prominent example of how the power of false rationalization drove the Liturgical Movement: As we shall see below, he provided theories about how traditional doctrines were to be understood in an ecumenical perspective, i.e., in a manner acceptable to those outside the Catholic Church and away from the true Faith.

His work is a prominent example of how the power of false rationalization drove the Liturgical Movement: As we shall see below, he provided theories about how traditional doctrines were to be understood in an ecumenical perspective, i.e., in a manner acceptable to those outside the Catholic Church and away from the true Faith.

In fact, Jungmann’s theological thinking turned out to be remarkably similar to that of the 16th-century Protestants, nothing less than a rejection of the doctrine of the Mass as the Catholic Church has always understood it.

Jungmann’s privileged position as a consulter to Pius XII’s Liturgical Commission secured the adoption of some of his ideas for the 1955 Holy Week reforms. It is of the greatest significance that the rest would find a ready acceptance in Vatican II’s Liturgy Constitution (he was a member of the Preparatory Commission) and in the Novus Ordo Mass (he was a member of Bugnini’s Consilium).

Thus stands revealed the direct link between the Modernism condemned by Pope Pius X and the fateful Article 7 of the 1969 General Instruction of the Novus Ordo, (1) which defined the Mass in a Protestant sense, as “the Lord’s Supper” and the gathering of the People of God.

Attack on the Mass from inside the Church

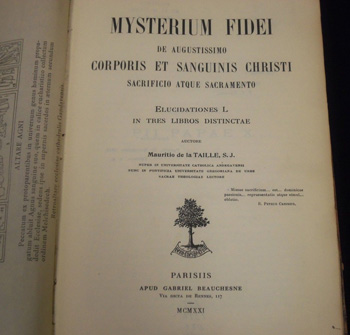

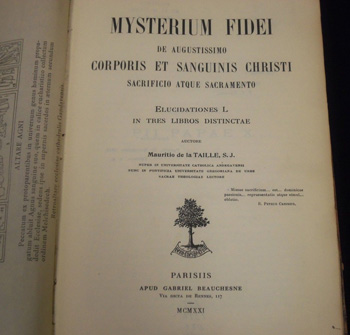

The theoretical antecedents for Article 7 go back to the early years of the 20th century to the publication of a book, Mysterium Fidei, (2) which was extremely influential in the Liturgical Movement. Its author, Fr. Maurice de la Taille, SJ, proposed, contrary to the teaching of the Fathers of the Church, (3) St. Thomas Aquinas (4) and the Council of Trent, (5) that the Mass does not contain any reality of immolation.

We can now see how this theory, put forward in 1921, had such potentially devastating consequences for the Church. For without the mystical immolation of the sacrificial Lamb on the altar, there would be no need for a sacrificing priest. The Mass would be reduced to a simple oblation, an offering of praise and thanksgiving by the community. The primary agents of the Eucharist would, therefore, be the People of God who, through their Baptism, offer the Mass through their representative, the priest. (6)

We can now see how this theory, put forward in 1921, had such potentially devastating consequences for the Church. For without the mystical immolation of the sacrificial Lamb on the altar, there would be no need for a sacrificing priest. The Mass would be reduced to a simple oblation, an offering of praise and thanksgiving by the community. The primary agents of the Eucharist would, therefore, be the People of God who, through their Baptism, offer the Mass through their representative, the priest. (6)

This corporate model was termed by de la Taille the “sacrifice of the Church” to replace the sacrifice of Christ performed uniquely by the ordained minister. (7) It became the dominant perspective of the Liturgical Movement and was promoted by the key figures of the nouvelle théologie.

Crucially, it was seen as a major ecumenical advance because it removed the Protestant objection to the Mass as the means of applying the merits of the Cross to souls through the mystical immolation of Christ on the altar. It was for this reason that the Anglican theologian, Dr. Eric Mascall, astutely observed that de la Taille’s theory “excited so violent a controversy in his own communion and so much admiration in ours.” (8)

One wonders how such a Catholic-sounding title as Mysterium Fidei was used for so Protestant-pleasing a book. But, then that is the modernist stock in trade.

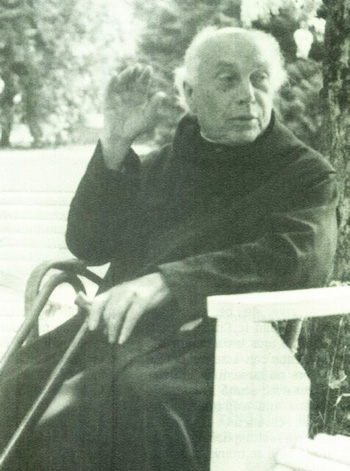

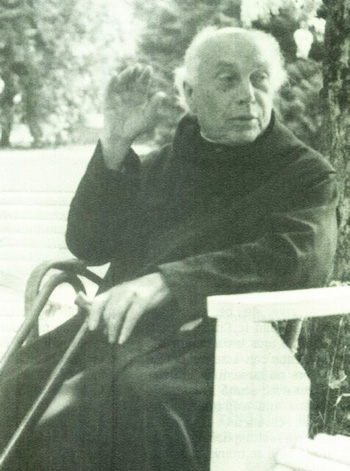

Lambert Beauduin was one of the first to declare de la Taille’s thesis an important theological development (9) (see

here) and described it as a welcome relief from an “all-absorbing obsession” with immolation. (10)

Lambert Beauduin was one of the first to declare de la Taille’s thesis an important theological development (9) (see

here) and described it as a welcome relief from an “all-absorbing obsession” with immolation. (10)

Karl Rahner considered de la Taille’s work as both stimulating and illuminating. (11) In his opinion, Mysterium Fidei “ought to have been read by every theologian in the field of the new and actively researching theology.” (12)

Henri de Lubac gloated in 1967 on the eve of the launching of the Novus Ordo Mass that de la Taille’s liturgical theology had gained the ascendancy: “The immense opposition he aroused in Mysterium Fidei is now only a memory and the essence of what he taught is now commonly accepted.” (13)

Accepted by whom? De Lubac’s terms of reference were limited to the narrow consensus of liturgical experts, but the broad swathe of faithful Catholics went on believing in the Mass as a mystical Mount Calvary, not a Protestant “Lord’s Supper” as Article 7 would indicate.

Joseph Jungmann’s sacramental theology borrowed heavily from de la Taille in the following ways:

The ‘no immolation’ theory

Despite the teaching of Pius XII (14) that the Mass is the re-presentation of Calvary and, therefore, contains an immolation, Jungmann insisted: “This re-presentation is indeed some sort of offering (offerre), but is not properly a sacrificial offering (sacrificari), an immolation.” (15)

In other words he was saying that the sacrifice of the Mass is not the self-same reality as the sacrifice of the Cross and that the mystical immolation that takes place in it is not a real and actual one. But here is the progressivist poison: if the Church commits her infallible authority to a doctrine that has no basis in objective reality, then, how can we believe that anything she teaches is true?

In other words he was saying that the sacrifice of the Mass is not the self-same reality as the sacrifice of the Cross and that the mystical immolation that takes place in it is not a real and actual one. But here is the progressivist poison: if the Church commits her infallible authority to a doctrine that has no basis in objective reality, then, how can we believe that anything she teaches is true?

How did Jungmann seek to justify his departure from what the Council of Trent had laid down as de fide teaching on the Mass? He alleged that the Church had never been concerned about a distinction between an oblation and an immolation (16) until “the pressure of controversy” generated by the Pseudo-Reformation forced the Church to come up with a theory of immolation. (17)

Jungmann stated: “Thinking of the Mass almost exclusively as a sacrifice is a one-sided attitude resulting from the doctrinal controversies of the 16th century.” (18) Here the progressivist poison is injected: his readers are to take home the message that the Mass as a real sacrifice was not of Apostolic origin.

The ‘sacrifice of the Church’ (19)

Jungmann proposed his own (or rather de la Taille’s) doctrine of the Mass:

“But when apologetic interests receded and the question once more arose as to what is the meaning and the purpose of the Mass in the organization of ecclesiastical life, it was precisely this point, the sacrifice of the Church, which came to the fore. ... There is nothing plainer than the thought that in the Mass the Church, the people of Christ, the congregation here assembled, offers up the sacrifice to Almighty God.” (20)

But his use of the word “sacrifice” was deliberately confused to conceal what he really meant: an offering of praise and thanksgiving by the community. (21)

Continued

His concern was to amass “evidence” to show that, soon after the early years of Christianity, the Church’s liturgy had become “doctrinally corrupt” in its theology of the Mass and the priesthood. His magnum opus was an endeavor of large proportions. It was as if he had set out to bury the Roman Rite under a complex web of falsehoods and was building an elaborate funerary monument or vast mortuary palace to commemorate its passing.

But, of course, he did not succeed, no more than had the Protestants of the Pseudo-Reformation who embarked on the same quest. For the traditional Mass has unfailingly confirmed throughout the ages the Faith of the Apostles in the true meaning of the Holy Sacrifice, the Real Presence and their own priesthood.

A front for Neo-Modernism

Where Jungmann did, however, achieve success was in influencing Church leaders and policy makers to accept his progressivist or neo-modernist ideas.

Fr. Josef Jungmann, the ‘man of the hour’ in the Liturgical Reform

In fact, Jungmann’s theological thinking turned out to be remarkably similar to that of the 16th-century Protestants, nothing less than a rejection of the doctrine of the Mass as the Catholic Church has always understood it.

Jungmann’s privileged position as a consulter to Pius XII’s Liturgical Commission secured the adoption of some of his ideas for the 1955 Holy Week reforms. It is of the greatest significance that the rest would find a ready acceptance in Vatican II’s Liturgy Constitution (he was a member of the Preparatory Commission) and in the Novus Ordo Mass (he was a member of Bugnini’s Consilium).

Thus stands revealed the direct link between the Modernism condemned by Pope Pius X and the fateful Article 7 of the 1969 General Instruction of the Novus Ordo, (1) which defined the Mass in a Protestant sense, as “the Lord’s Supper” and the gathering of the People of God.

Attack on the Mass from inside the Church

The theoretical antecedents for Article 7 go back to the early years of the 20th century to the publication of a book, Mysterium Fidei, (2) which was extremely influential in the Liturgical Movement. Its author, Fr. Maurice de la Taille, SJ, proposed, contrary to the teaching of the Fathers of the Church, (3) St. Thomas Aquinas (4) and the Council of Trent, (5) that the Mass does not contain any reality of immolation.

Ahead of his time, de la Taille set the framework for the Novus Ordo Missae

This corporate model was termed by de la Taille the “sacrifice of the Church” to replace the sacrifice of Christ performed uniquely by the ordained minister. (7) It became the dominant perspective of the Liturgical Movement and was promoted by the key figures of the nouvelle théologie.

Crucially, it was seen as a major ecumenical advance because it removed the Protestant objection to the Mass as the means of applying the merits of the Cross to souls through the mystical immolation of Christ on the altar. It was for this reason that the Anglican theologian, Dr. Eric Mascall, astutely observed that de la Taille’s theory “excited so violent a controversy in his own communion and so much admiration in ours.” (8)

One wonders how such a Catholic-sounding title as Mysterium Fidei was used for so Protestant-pleasing a book. But, then that is the modernist stock in trade.

Dom Lambert Beauduin

Karl Rahner considered de la Taille’s work as both stimulating and illuminating. (11) In his opinion, Mysterium Fidei “ought to have been read by every theologian in the field of the new and actively researching theology.” (12)

Henri de Lubac gloated in 1967 on the eve of the launching of the Novus Ordo Mass that de la Taille’s liturgical theology had gained the ascendancy: “The immense opposition he aroused in Mysterium Fidei is now only a memory and the essence of what he taught is now commonly accepted.” (13)

Accepted by whom? De Lubac’s terms of reference were limited to the narrow consensus of liturgical experts, but the broad swathe of faithful Catholics went on believing in the Mass as a mystical Mount Calvary, not a Protestant “Lord’s Supper” as Article 7 would indicate.

Joseph Jungmann’s sacramental theology borrowed heavily from de la Taille in the following ways:

The ‘no immolation’ theory

Despite the teaching of Pius XII (14) that the Mass is the re-presentation of Calvary and, therefore, contains an immolation, Jungmann insisted: “This re-presentation is indeed some sort of offering (offerre), but is not properly a sacrificial offering (sacrificari), an immolation.” (15)

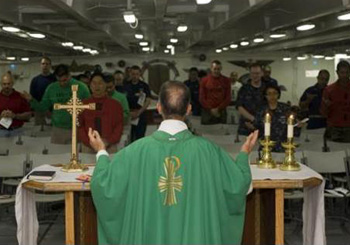

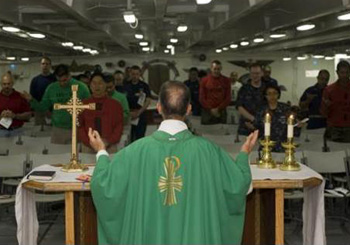

Jungmann rejected the central notion of the Mass as a renewal of Christ's sacrifice at Calvary

How did Jungmann seek to justify his departure from what the Council of Trent had laid down as de fide teaching on the Mass? He alleged that the Church had never been concerned about a distinction between an oblation and an immolation (16) until “the pressure of controversy” generated by the Pseudo-Reformation forced the Church to come up with a theory of immolation. (17)

Jungmann stated: “Thinking of the Mass almost exclusively as a sacrifice is a one-sided attitude resulting from the doctrinal controversies of the 16th century.” (18) Here the progressivist poison is injected: his readers are to take home the message that the Mass as a real sacrifice was not of Apostolic origin.

The ‘sacrifice of the Church’ (19)

Jungmann proposed his own (or rather de la Taille’s) doctrine of the Mass:

“But when apologetic interests receded and the question once more arose as to what is the meaning and the purpose of the Mass in the organization of ecclesiastical life, it was precisely this point, the sacrifice of the Church, which came to the fore. ... There is nothing plainer than the thought that in the Mass the Church, the people of Christ, the congregation here assembled, offers up the sacrifice to Almighty God.” (20)

But his use of the word “sacrifice” was deliberately confused to conceal what he really meant: an offering of praise and thanksgiving by the community. (21)

Continued

- “The Lord’s Supper, or Mass, is the sacred meeting or congregation of the people of God assembled, the priest presiding, to celebrate the memorial of the Lord.”

- 2. M. de la Taille, Mysterium Fidei, Paris, G. Beauchesne, 1921.

- St Augustine, for example, taught that a real immolation takes place in the Mass: “Was not Christ immolated only once in His very Person? In the Sacrament, nevertheless, He is immolated for the people not only on every Easter Solemnity, but on every day; and a man would not be lying if, when asked, he were to reply that Christ is being immolated” (Letters 98:9).

- With reference to the Eucharist, St. Thomas Aquinas says: “It is proper to this Sacrament that Christ should be immolated in its celebration,” for the Old Testament contains only figures of His Sacrifice (Summa, III, 83, 1).

- The Council of Trent session 22, chapter 2, affirmed: “In this Divine Sacrifice, which is celebrated in the Mass, that same Christ is contained and immolated in an unbloody manner, who once offered himself in a bloody manner on the altar of the Cross.”

- Fr. de la Taille stated: “The authors of the sacrifice, in a manner that is proper and personal to them, are the faithful whose gifts are by the priest’s hands addressed to God under the form of the Body and Blood of Jesus Christ”(The Mystery of Faith and Human Opinion, New York: Longmans, Green and Co., 1930, p. 134).

- Fr. de la Taille stated: “The power and the act of sacrificing passes from the Head to the body” (Mysterium Fidei, vol. 2, p. 193).

- E. L. Mascall, Christ, the Christian and the Church (London: Longmans, 1946), p. 168 apud Francis Clark, Eucharistic Sacrifice and the Reformation (London: Darton, Longman and Todd, 1960), pp. 263-264.

Prominent among those who opposed de la Taille were Fr. Alfred Swaby, “A New Theory of Eucharistic Sacrifice, American Ecclesiastical Review, 69 (1923), pp. 460-47 3; Fr. Vincent McNabb, “A New Theory of the Sacrifice of the Mass,” Irish Ecclesiastical Review 23 (1924), pp. 561-573; and Dom Anscar Vonier, Abbot of Buckfast Abbey, A Key to the Doctrine of the Eucharist (London: Burns, Oates & Washbourne, 1925). - L. Beauduin, “Le Saint Sacrifice de la Messe: A propos d'un Livre Récent,” in Les questions liturgiques et paroissiales, vol. VII, 1922, pp. 197-198. He stated: “Le Christ n'a été immolé réellement qu'une seule fois: ce fut dans le sacrifice sanglant de la Passion. Par contre ni la Cène, ni la Messe ne contiennent une Immolation réelle et distincte d'aucune sorte.” (Christ was immolated in reality only once: that was in the bloody sacrifice of the Passion. However, neither the Supper nor the Mass contains a real and distinct Immolation of any kind.”)

- Ibid., p. 202: “La thèse du P. de la Taille est une délivrance et un soulagement.” (Fr. de la Taille’s thesis is a liberation and a relief.)

- Karl Rahner opined: “What is it that makes the properly historical in studies like those of de Lubac or de la Taille so stimulating and to the point? Surely it is the art of reading texts in such a way that they become not just votes cast in favour of or against our current positions (positions taken up long ago), but say something to us that we in our time have not considered at all or not closely enough about reality itself.” “The Prospects for Dogmatic Theology,” in Theological Investigations, vol. I (Baltimore: Helicon Press, 1961), pp. 9-10.

- Karl Rahner, “Latin as a Church language,” in Theological Investigations, vol. V (London: Darton, Longman and Todd, 1966), p. 397.

- H. de Lubac, The Mystery of the Supernatural (Herder and Herder, 1967), p. 4.

- Pius XII had said in Mediator Dei, n. 91: “The unbloody immolation at the words of Consecration, when Christ is made present upon the altar in the state of a victim, is performed by the priest and by him alone, as the representative of Christ and not as the representative of the faithful.”

- Jungmann, The Mass of the Roman Rite, vol. 1, p. 184.

- Ibid. But St. Thomas Aquinas had already disproved this point in the Summa ( q. 85, art. 3) when he said that “every immolation is an oblation, but not conversely,” i.e., not every oblation is an immolation.

- Jungmann, The Mass of the Roman Rite, vol. 1, p. 184.

- Jungmann, Announcing the Word of God, trans. from the German by Ronald Walls (London : Burns & Oates, 1967), p. 112.

- Jungmann was aware of his debt to de la Taille on this point. In fact, Jungmann states (cf. The Mass of the Roman Rite, vol. 1, p. 182, note 21): “In recent times the sacrifice of the Church has been given theological emphasis by M. de la Taille, Mysterium Fidei (Paris, 1921).”

- Ibid., p. 180.

- Jungmann believed that the Eucharist “is not primarily an object for our adoration, nor yet for the nourishment of the soul, but is, as its name indicates, a sacrifice of thanksgiving, of sacrifice within the assembled congregation.” He also affirmed that this communal celebration is the “primary and true function” of the Mass (Announcing the Word of God, p. 110)

Posted December 2, 2015

______________________

______________________

Volume I |

Volume II |

Volume III |

Volume IV |

Volume V |

Volume VI |

Volume VII |

Volume VIII |

Volume IX |

Volume X |

Volume XI |

Special Edition |