Traditionalist Issues

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Dialogue Mass - XXXV

Sabotaging the Elevation & the Consecration

Jungmann shared some of the belligerently anti-Catholic attitudes that drove the Protestant “Reformation,” as we can see from the following criticisms he made of the Elevation:

No innovation

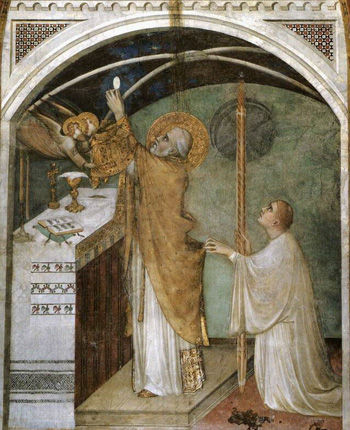

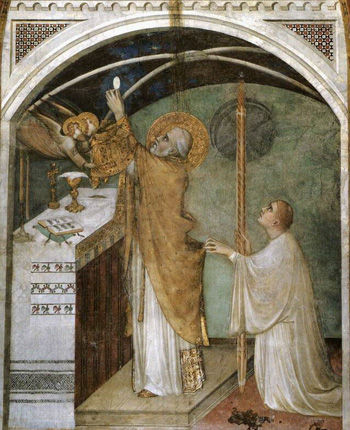

The first critics to attack the Elevation as a novelty were the 16th century Protestants (3) in a vain attempt to show that it was an unauthentic “Romish” [Roman] addition. Historically, there were and still are, a number of minor elevations at different points in the Roman Mass. In fact, the custom of elevation – in the sense of showing the Blessed Sacrament to the people before Communion for their adoration before reception – was already established in the Apostolic Constitutions of the 4th century. (4) In pre-medieval times, the priest held the Host at shoulder level during the Consecration.

So, by the 13th century, it was only a question of raising the consecrated Host a few inches higher for the people to see and adore – hardly a startling revolution. The “new” ritual, being rooted in the centuries-old pious customs of the faithful, grew naturally and organically from the living tradition, as a tree puts forth its blossoms in due season.

So, by the 13th century, it was only a question of raising the consecrated Host a few inches higher for the people to see and adore – hardly a startling revolution. The “new” ritual, being rooted in the centuries-old pious customs of the faithful, grew naturally and organically from the living tradition, as a tree puts forth its blossoms in due season.

The Elevation was, therefore, a development of the liturgical tree rather than an innovation. It was also regarded as a mystical symbol of Christ being raised on the Cross at Calvary, an effective aid in recalling the Passion and Death of Christ. Most significantly, it marked the moment of Christ’s descent upon the altar in the miracle of transubstantiation.

Why the objection?

Jungmann tried to make out that this was not the teaching of the early Church. The medieval emphasis on the “descent of the sacred mystery” was, he alleged, a harmful error because it “led to a lessening regard for the oblation which we ourselves offer up and in which we offer ourselves as members of the Body of Christ, and a greater attention to the act of transubstantiation.” (5)

The ‘moment of Consecration’

For those who disbelieved in the act of transubstantiation or wanted to ignore it, Jungmann provided the following “justification”:

“In general, Christian antiquity even until way into the Middle Ages manifested no particular interest regarding the determination of the precise moment of the Consecration. Often reference was made merely to the entire Eucharistic Prayer.” (6)

This was his way of dismissing the Scholastic theology of the Middle Ages by making this vital issue (an exact moment of Consecration) seem like a pointless academic dispute – an analogue to the angels-on-heads-of-pins conundrum – or a “magic moment” theory which can be laughed away. In this way, the progressivists continue to ridicule and undermine old certitudes and fixed beliefs. It was an example of how Jungmann indulged in polemics (7) to challenge traditional values whenever historical evidence was lacking to prove his point.

He was quite wrong, for evidence exists that the early Fathers of the Church testified to their belief in an exact moment of Consecration occurring immediately after Christ’s words are spoken by the priest. (8)

Christ’s descent onto the altar at Mass

In objecting to the “descent of the sacred mystery,” Jungmann was placing himself outside the entire tradition of the Church’s sacramental theology, for the whole doctrine of transubstantiation is intimately connected with the Incarnation – as Pope Leo XIII pointed out: “The Eucharist, according to the testimony of the holy Fathers, should be regarded as, in a manner, a continuation and extension of the Incarnation.” (9) [emphasis added]

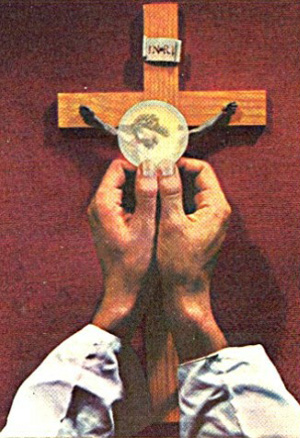

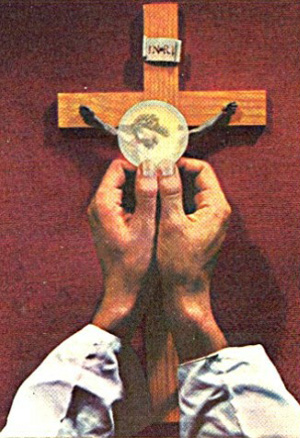

The ‘scandal of particularity’ (10)

Jungmann did not accept the essential point held by the Church Fathers that, just as the Son of God descended at a precise moment into the chaste womb of the Blessed Virgin Mary, so He descends every day into the hands of the priest at a precise moment after the words of Consecration. It was to reinforce this analogy that the Church used the Preface of Christmas in the traditional Mass of Corpus Christi – at least up until 1955 when that Preface was swept away by the stroke of a pen in the liturgical “purges” made by Pius XII. (11)

Jungmann did not accept the essential point held by the Church Fathers that, just as the Son of God descended at a precise moment into the chaste womb of the Blessed Virgin Mary, so He descends every day into the hands of the priest at a precise moment after the words of Consecration. It was to reinforce this analogy that the Church used the Preface of Christmas in the traditional Mass of Corpus Christi – at least up until 1955 when that Preface was swept away by the stroke of a pen in the liturgical “purges” made by Pius XII. (11)

Jungmann could not swallow the idea of a “precise moment” of Consecration (12) enacted by the celebrating priest without suffering acute liturgical indigestion. Instead, he posited that the “entire Eucharistic Prayer” from the beginning of the Preface up to the Our Father was consecratory. He also sustained that the Consecration was not effected just by a prayer of the priest but by the whole assembly, and that it should include an active role for the congregation (expression of thanksgiving, various responses and acclamations, reciting the Sanctus etc.)

Was the Elevation removed from the N.O.?

No, in the sense that the Elevation, together with the ringing of bells, has not been specifically prohibited, as it had been in Cranmer’s 1549 Prayer Book; it is still tolerated as an option for the more conservatively inclined.

Yes, in the sense that the General Instruction of the Novus Ordo has replaced the rubric in the traditional Missal concerning elevation (“elevat”), with the instruction that the priest simply shows (“ostendit”) the Host. The General Instruction also calls the Eucharistic Prayer, as a generic whole, the “high point” and the “center and summit of the entire celebration,” (13) a title of honor traditionally given to the Consecration as Fr. Gihr explains:

Yes, in the sense that the General Instruction of the Novus Ordo has replaced the rubric in the traditional Missal concerning elevation (“elevat”), with the instruction that the priest simply shows (“ostendit”) the Host. The General Instruction also calls the Eucharistic Prayer, as a generic whole, the “high point” and the “center and summit of the entire celebration,” (13) a title of honor traditionally given to the Consecration as Fr. Gihr explains:

“The moment of Consecration is the moment most important and solemn, the most sublime and touching, the most holy and fruitful of the whole sacrificial celebration; for it includes that glorious and unfathomably profound work, namely, the accomplishment of the Eucharistic Sacrifice, in which all the marvels of God’s love are concentrated as in a focus of heat and light.” (14)

But, it was precisely on the grounds of this focus on the Blessed Sacrament that Jungman criticized the Elevation. As we have seen, he wanted to deflect attention away from the Real Presence and onto the presence of the people and, accordingly, devised a reform of the Mass that would reflect this new orientation. It is entirely to be expected that, as Cardinal Ottaviani pointed out in his Critical Examination of the Nouvs Ordo, “The central role of the Real Presence has been suppressed. It has been removed from the place it so resplendently occupied in the old liturgy.” (15)

Continued

Progressivism's objections against the Elevation are the same as those of Protestantism

- It was an “intrusion of a very notable innovation” into the Mass; (1)

- It resulted from some pedantic and futile quibbles among medieval theologians regarding a “precise moment of Consecration”;

- It was closely connected with superstitious practices arising from popular perceptions of the Grail legend;

- It caused harm to the spiritual lives of the faithful by inducing them to be satisfied with looking at rather than receiving the Host;

- It was the cause of disorderly conduct in church as people jostled one another for a view of the elevated Host;

- It caused them to neglect the rest of the Mass as they raced from church to church to be present only at each “showing” of the Host and Chalice.

No innovation

The first critics to attack the Elevation as a novelty were the 16th century Protestants (3) in a vain attempt to show that it was an unauthentic “Romish” [Roman] addition. Historically, there were and still are, a number of minor elevations at different points in the Roman Mass. In fact, the custom of elevation – in the sense of showing the Blessed Sacrament to the people before Communion for their adoration before reception – was already established in the Apostolic Constitutions of the 4th century. (4) In pre-medieval times, the priest held the Host at shoulder level during the Consecration.

Thomas Becon & Josef Jungmann are

on the same page

The Elevation was, therefore, a development of the liturgical tree rather than an innovation. It was also regarded as a mystical symbol of Christ being raised on the Cross at Calvary, an effective aid in recalling the Passion and Death of Christ. Most significantly, it marked the moment of Christ’s descent upon the altar in the miracle of transubstantiation.

Why the objection?

Jungmann tried to make out that this was not the teaching of the early Church. The medieval emphasis on the “descent of the sacred mystery” was, he alleged, a harmful error because it “led to a lessening regard for the oblation which we ourselves offer up and in which we offer ourselves as members of the Body of Christ, and a greater attention to the act of transubstantiation.” (5)

The ‘moment of Consecration’

For those who disbelieved in the act of transubstantiation or wanted to ignore it, Jungmann provided the following “justification”:

“In general, Christian antiquity even until way into the Middle Ages manifested no particular interest regarding the determination of the precise moment of the Consecration. Often reference was made merely to the entire Eucharistic Prayer.” (6)

This was his way of dismissing the Scholastic theology of the Middle Ages by making this vital issue (an exact moment of Consecration) seem like a pointless academic dispute – an analogue to the angels-on-heads-of-pins conundrum – or a “magic moment” theory which can be laughed away. In this way, the progressivists continue to ridicule and undermine old certitudes and fixed beliefs. It was an example of how Jungmann indulged in polemics (7) to challenge traditional values whenever historical evidence was lacking to prove his point.

He was quite wrong, for evidence exists that the early Fathers of the Church testified to their belief in an exact moment of Consecration occurring immediately after Christ’s words are spoken by the priest. (8)

Christ’s descent onto the altar at Mass

In objecting to the “descent of the sacred mystery,” Jungmann was placing himself outside the entire tradition of the Church’s sacramental theology, for the whole doctrine of transubstantiation is intimately connected with the Incarnation – as Pope Leo XIII pointed out: “The Eucharist, according to the testimony of the holy Fathers, should be regarded as, in a manner, a continuation and extension of the Incarnation.” (9) [emphasis added]

The ‘scandal of particularity’ (10)

In the Novus Ordo the Consecration is supposed to be made by the whole congregation

Jungmann could not swallow the idea of a “precise moment” of Consecration (12) enacted by the celebrating priest without suffering acute liturgical indigestion. Instead, he posited that the “entire Eucharistic Prayer” from the beginning of the Preface up to the Our Father was consecratory. He also sustained that the Consecration was not effected just by a prayer of the priest but by the whole assembly, and that it should include an active role for the congregation (expression of thanksgiving, various responses and acclamations, reciting the Sanctus etc.)

Was the Elevation removed from the N.O.?

No, in the sense that the Elevation, together with the ringing of bells, has not been specifically prohibited, as it had been in Cranmer’s 1549 Prayer Book; it is still tolerated as an option for the more conservatively inclined.

Our Lord becomes present in the Host immediately after the priest says the words

“The moment of Consecration is the moment most important and solemn, the most sublime and touching, the most holy and fruitful of the whole sacrificial celebration; for it includes that glorious and unfathomably profound work, namely, the accomplishment of the Eucharistic Sacrifice, in which all the marvels of God’s love are concentrated as in a focus of heat and light.” (14)

But, it was precisely on the grounds of this focus on the Blessed Sacrament that Jungman criticized the Elevation. As we have seen, he wanted to deflect attention away from the Real Presence and onto the presence of the people and, accordingly, devised a reform of the Mass that would reflect this new orientation. It is entirely to be expected that, as Cardinal Ottaviani pointed out in his Critical Examination of the Nouvs Ordo, “The central role of the Real Presence has been suppressed. It has been removed from the place it so resplendently occupied in the old liturgy.” (15)

Continued

- J.A. Jungmann, The Mass of the Roman Rite, vol. 2, p. 108. In an astonishing display of hypocrisy, he expressed his outrage that the Elevation had been introduced into the Canon “which for ages had been regarded as an inviolable sanctuary.” At the time he wrote those words, Jungmann was planning to violate that very sanctuary with his own reforms that would eventually become evident in the Novus Ordo.

- Council of Trent, 22nd session, canon 7: “If anyone says that the ceremonies, vestments and outward signs, which the Catholic Church uses in the celebration of Masses, are incentives to impiety rather than stimulants to piety, let him be anathema.”

- A typical 16th century example is the criticism made by Thomas Cranmer’s Chaplain, Thomas Becon, who said with reference to the Elevation: “Verily it is not much more than 300 years old. Let the lying papists be ashamed to brag that their devilish mass came from the Apostles; seeing it is a new and late invention of the antichrist. (Apud ‘Displaying of the Popish Mass’ in Prayers and Other Pieces of Thomas Becon, Publication of the Parker Society, edited by Rev. John Ayre, Cambridge University Press, 1844, vol. 3, p. 270)

- Adrian Fortescue, The Mass, A Study of the Roman Liturgy, London-New York-Toronto: Longmans, Green and Co, , 1913, pp. 337-338.

- J.A. Jungmann, The Mass of the Roman Rite, vol. 2, pp. 101-102.

- Ibid., pp. 203-204, note 9.

- “Polemics” derives from the Greek polemos, (war) and polemikos (warlike, hostile). It can be aptly applied to Jungmann’s approach, for he went to war against the Mass of the Roman Rite.

- St. Justin Martyr (2nd century): “As we have been taught, the food which has been made Eucharist by the word of prayer, which is His Word, and by change of which our blood and flesh is nourished, is both the Flesh and Blood of the incarnated Christ.” (1 Apology, chap. 66); With reference to the Roman Canon in the 4th century, St. Ambrose said: “When the moment comes for bringing the Most Holy Sacrament into being, the priest does not use his own words any longer: he uses the words of Christ. Therefore, it is Christ’s Word that brings this Sacrament into being… Before the Consecration, it was not the Body of Christ, but after the Consecration I tell you it is now the Body of Christ.” (De Sacramentis, book 4, chap. 4, n.16); St. John Chrysostom (4th century) said: “The priest standing there in the place of Christ says these words but their power and grace are from God. ‘This is My Body,’ he says, and these words transform the gifts.” (Homily 1, 6, Homilies on the Treachery of Judas); St. Gregory the Great (7th century) rebuked those who doubted that “at the very moment of immolation, the heavens are opened by the voice of the priest, [and] that the choirs of angels are present at this Mystery of Jesus Christ.” (The Dialogues of Saint Gregory the Great, trans. Edmund G. Gardner, London and Boston, 1911, book 4, chap 58, p. 256)

- Pope Leo XIII, Mirae caritatis, On the Holy Eucharist, 1902, n. 7 .

- This phrase denotes the reaction of sceptics to the truth that God became man at a particular moment of time and in a particular place and that He is the unique Saviour of mankind. And it is used with reference to those who disbelieve that God intervenes in the particularities of human affairs. It also covers any of the “exclusive” claims of the Catholic Church, e.g., to possess the one true Faith or to be the one Ark of Salvation for all, which are a stumbling block for many.

- The Preface of Christmas on the feast of Corpus Christi was suppressed by the decree, Cum nostra hac aetate (Acta Apostolicae Sedis 47, 1955, n. 8, p. 224) on the pretext of “simplifying” the liturgy. As a result, the Corpus Christi Mass of the 1962 Missal has just the Common Preface. At the same time, the Octave of Corpus Christi was suppressed, as well as the Mass of the Sunday within the Octave.

- Nor could the Catechism of the Catholic Church which merely states: “The Eucharistic presence of Christ begins at the moment of the Consecration.” (n. 1377) But, St. Thomas Aquinas taught that this happens immediately after (not at) the words of Consecration, so that transubstantiation “is wrought by Christ’s words, which are spoken by the priest, so that the last instant of pronouncing the words is the first instant in which Christ’s Body is in the Sacrament; and that the substance of the bread is there during the whole preceding time.”(Summa Theologiae III, q. 75, a. 7)

- General Instruction, nn. 30, 78.

- Nicholas Gihr, The Holy Sacrifice of the Mass, Fribourg: Herder, 1902, pp. 631-632.

- Ottaviani Intervention, chap. 4, 1969.

Posted June 17, 2016

______________________

______________________

Volume I |

Volume II |

Volume III |

Volume IV |

Volume V |

Volume VI |

Volume VII |

Volume VIII |

Volume IX |

Volume X |

Volume XI |

Special Edition |