Traditionalist Issues

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Dialogue Mass - LXXVIII

‘The Mass Should be Ratified by the People’

One of the many misunderstandings brought about by the 20th century liturgical reforms is that the choir is simply a section of the congregation, a mixed group of lay people whose role is to lead the rest of the faithful in song. That may be true in Protestant temples, and is certainly the case in the Novus Ordo liturgy, as the post-Vatican II English Bishops explained:

“The choir remains at all times a part of the assembly. It can serve the assembly by leading it in sung prayer and by reinforcing or enhancing the song of the assembly.” (1)

“The choir remains at all times a part of the assembly. It can serve the assembly by leading it in sung prayer and by reinforcing or enhancing the song of the assembly.” (1)

But it is completely foreign to a Catholic understanding of the choir as a clerical entity. The various forms of liturgical chant were originally written by clerics for their own use in choir, not for the congregation.

Pope Pius X’s reference in his motu proprio Tra le Sollecitudini to the “Choir of Levites” is of the greatest significance in identifying the role of singers as inherently liturgical and, therefore, clerical in nature. It said in a nutshell all we need to know about the distinction between the clergy and the rest of the faithful as far as the duty to sing the liturgy is concerned.

In the Old Testament, the Levites were set apart and consecrated to God, either as priests to offer sacrifice, or as their assistants in various sacral roles, including singing. (2) In the New Testament, the choir was meant to be a separate entity composed of clerics whose role was to assist the celebrating priest in his task of mediating the liturgy to the faithful.

Where there were insufficient clerics available, their numbers could be supplemented by laymen, but only on the understanding, as Pius X explained, that “singers in the church, even when they are laymen, are really taking the place of the ecclesiastical choir.” (3)

Might we not find it ironic that the cliché “preaching to the choir” (the seating area once reserved for the clergy in the great cathedrals of Christendom) can no longer be understood in its original sense because the clergy themselves have voided it of meaning?

Might we not find it ironic that the cliché “preaching to the choir” (the seating area once reserved for the clergy in the great cathedrals of Christendom) can no longer be understood in its original sense because the clergy themselves have voided it of meaning?

It is not without significance that the progressivist reformers showed no awareness that the distinction between the clergy and the laity is “by divine institution,” as the 1917 Code of Canon Law stated. (4) Nor did they acknowledge that this divinely appointed distinction must be observed in the liturgy, as in every other aspect of the Church’s life – hence their opposition to the idea that it is the right and duty of the clergy, not the laity, to sing the liturgy.

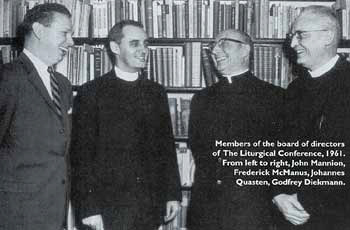

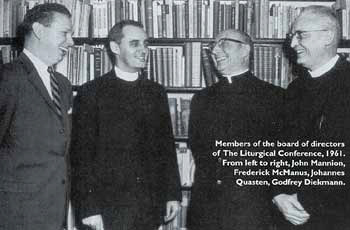

As their chief spokesman, Mgr. Frederick McManus, wrote in 1956, when explaining the rationale behind Pius XII’s reforms in which he himself was a major player:

“When a choir chants those parts of Holy Mass or other rites that belong to the people, the faithful are not doing what they are appointed by their baptismal character to do ‒ namely, worship God as members of Christ. In the restored Holy Week, the clear directions indicate again and again that the people should not be denied this right.” (5) [Emphasis added]

Every one of these claims is specious, anti-clerical and theologically incorrect. The idea that parts of the Mass “belong to the people” – in the sense that they alone must sing or recite them – was an invention of the Liturgical Movement. (6) The reformers saw everything in terms of a power struggle, with Vatican II representing liberation from the clutches of a dominating clergy and a return to “ownership” of the liturgy by the People of God.

Every one of these claims is specious, anti-clerical and theologically incorrect. The idea that parts of the Mass “belong to the people” – in the sense that they alone must sing or recite them – was an invention of the Liturgical Movement. (6) The reformers saw everything in terms of a power struggle, with Vatican II representing liberation from the clutches of a dominating clergy and a return to “ownership” of the liturgy by the People of God.

As for the presumed “right” of the laity to active participation by reason of their baptismal character, this illusory principle does not correlate with any Catholic doctrine. It is inadmissible to claim that Baptism empowers lay people to assume the divinely ordained role of the priest who baptized them, as if he were thereby handing them the means to undermine his own ministry.

Yet that is the tacit assumption and inescapable conclusion of §14 of the Vatican II Liturgy Constitution Sacrosanctum Concilium, which states that “active participation … is their right and duty by reason of their baptism.” Baptism only gives the laity the right to have the Mass and Sacraments made available to them and to participate spiritually in these means of salvation.

‘Active participation’ in the Consecration

As “active participation” was to be a dimension of everything that is done in the liturgy, all members of the congregation are deemed to be wholly involved in every part of the proceedings, including the Consecration. In the Novus Ordo Mass, at the point where the so-called “Institution Narrative” replaced the Words of Consecration, the “people’s portion” is to say or sing a series of “Memorial Acclamations” as part of the so-called Eucharistic Prayers (themselves a replacement for the traditional Canon).

The rationale behind this revolutionary reform was provided by Fr. Yves Congar, the chief proponent of the novel “theology of the liturgical assembly,” who stated with reference to the priest’s power to consecrate the bread and wine:

“This does not mean that he can do it alone, that is, when he remains alone. He does not, in other words, consecrate the elements by virtue of a power which is inherent in him.” (7)

‘Active participation’ favors heresy

According to this “new theology,” which echoes Protestant perspectives, it is the “active participation” of the gathered assembly talking and singing together that makes Christ present in the Eucharist. Consequently, the doctrine that the words uttered by the priest at the Consecration are the unique cause of the Real Presence in the Mass is never made clear in the Novus Ordo Mass. It is obvious that the reformers wanted both the Real Presence and the priest’s unique role in effecting transubstantiation to be ignored and forgotten.

Under the influence of progressivist reformers, the Vatican II Liturgy Constitution (and all subsequent documents from the Holy See and Episcopal Conferences) adopted the Protestant principle that the vocal responses of the gathered community are essential for the integrity of the liturgy. (8)

Under the influence of progressivist reformers, the Vatican II Liturgy Constitution (and all subsequent documents from the Holy See and Episcopal Conferences) adopted the Protestant principle that the vocal responses of the gathered community are essential for the integrity of the liturgy. (8)

Fr. Joseph Jungmann, who was no ordinary, run-of-the-mill liturgist ‒ he actually drafted some parts of the Liturgy Constitution ‒ favored this concept, as we can see from his description of the liturgies of the early Church:

“In the liturgical action the participation of the people was manifested especially by the fact that they did not merely listen to the prayers of the priest in silence but ratified them by their acclamations.” (9) [emphasis added]

Even the Canon of the Mass is not considered to be complete without the people’s Amen at the final Doxology. (10) Bugnini stated with reference to the Eucharistic Prayer: “They are to ratify with their ‘Amen’ what the priest has done and asked in the assembly’s name.” (11) [emphasis added]

The use of the term “ratify” as a necessary action on the part of the congregation is most illuminating. It reveals the intention of the reformers who devised the Novus Ordo Mass to embrace beliefs and practices not endorsed by the Church.

Pope Pius XII had specifically condemned those who “go so far as to hold that the people must confirm and ratify the Sacrifice if it is to have its proper force and value,” and added: “It is in no wise required that the people ratify what the sacred minister has done.” (Mediator Dei §§ 95-96)

Yet this was an indispensable requirement of the General Instruction, and was recognized as such by the English Bishops when they mentioned “the profound importance of the assembly’s ratification and acclamation” at the end of the Canon. (12)

Ratification, a term suggestive of heresy

The idea of the assembly’s “ratification” is doubly anomalous, a deviation not only from the millennial lex orandi, but also from the lex credendi. As a term borrowed from legal transactions, it gives the impression that the expressed consent of the people is necessary to make the Consecration officially valid, whereas its validity is ensured ex vi verborum, i.e., by virtue of the words of the priest alone.

The boot is on the other foot

Moreover, as only a higher authority can ratify a transaction, the further impression is given that the people occupy a superior plane to the celebrating priest. The agenda to undermine the traditional Catholic priesthood is revealed in this revolutionary model of “active participation” in which the proper relationship between the clergy and the laity has been reversed completely.

Moreover, as only a higher authority can ratify a transaction, the further impression is given that the people occupy a superior plane to the celebrating priest. The agenda to undermine the traditional Catholic priesthood is revealed in this revolutionary model of “active participation” in which the proper relationship between the clergy and the laity has been reversed completely.

But that reversal was precisely the objective of the Liturgical Movement.

Usurping God's authority

It is God Who is meant to ratify the Sacrifice of His Son, as is made clear in the Quam oblationem of the Canon, where the priest requests God to ratify (“ratam facere”) the Sacrifice he is about to offer in persona Christi.

As Dom Guéranger explained: “It must needs be ratified, approved, confirmed in Heaven, as a Thing most truly Good and Fitting. (13)

But then, as the evidence overwhelmingly shows, the Novus Ordo Mass was always a man-centred liturgy in which the People of God take centre stage.

Continued

The choir as part of the ‘assembly of God’

But it is completely foreign to a Catholic understanding of the choir as a clerical entity. The various forms of liturgical chant were originally written by clerics for their own use in choir, not for the congregation.

Pope Pius X’s reference in his motu proprio Tra le Sollecitudini to the “Choir of Levites” is of the greatest significance in identifying the role of singers as inherently liturgical and, therefore, clerical in nature. It said in a nutshell all we need to know about the distinction between the clergy and the rest of the faithful as far as the duty to sing the liturgy is concerned.

In the Old Testament, the Levites were set apart and consecrated to God, either as priests to offer sacrifice, or as their assistants in various sacral roles, including singing. (2) In the New Testament, the choir was meant to be a separate entity composed of clerics whose role was to assist the celebrating priest in his task of mediating the liturgy to the faithful.

Where there were insufficient clerics available, their numbers could be supplemented by laymen, but only on the understanding, as Pius X explained, that “singers in the church, even when they are laymen, are really taking the place of the ecclesiastical choir.” (3)

Pope Pius X wanted to return to choirs of male voices

It is not without significance that the progressivist reformers showed no awareness that the distinction between the clergy and the laity is “by divine institution,” as the 1917 Code of Canon Law stated. (4) Nor did they acknowledge that this divinely appointed distinction must be observed in the liturgy, as in every other aspect of the Church’s life – hence their opposition to the idea that it is the right and duty of the clergy, not the laity, to sing the liturgy.

As their chief spokesman, Mgr. Frederick McManus, wrote in 1956, when explaining the rationale behind Pius XII’s reforms in which he himself was a major player:

“When a choir chants those parts of Holy Mass or other rites that belong to the people, the faithful are not doing what they are appointed by their baptismal character to do ‒ namely, worship God as members of Christ. In the restored Holy Week, the clear directions indicate again and again that the people should not be denied this right.” (5) [Emphasis added]

Fr. McMannus, second from left, a strong advocate that the Mass ‘belongs to the people’

As for the presumed “right” of the laity to active participation by reason of their baptismal character, this illusory principle does not correlate with any Catholic doctrine. It is inadmissible to claim that Baptism empowers lay people to assume the divinely ordained role of the priest who baptized them, as if he were thereby handing them the means to undermine his own ministry.

Yet that is the tacit assumption and inescapable conclusion of §14 of the Vatican II Liturgy Constitution Sacrosanctum Concilium, which states that “active participation … is their right and duty by reason of their baptism.” Baptism only gives the laity the right to have the Mass and Sacraments made available to them and to participate spiritually in these means of salvation.

‘Active participation’ in the Consecration

As “active participation” was to be a dimension of everything that is done in the liturgy, all members of the congregation are deemed to be wholly involved in every part of the proceedings, including the Consecration. In the Novus Ordo Mass, at the point where the so-called “Institution Narrative” replaced the Words of Consecration, the “people’s portion” is to say or sing a series of “Memorial Acclamations” as part of the so-called Eucharistic Prayers (themselves a replacement for the traditional Canon).

The rationale behind this revolutionary reform was provided by Fr. Yves Congar, the chief proponent of the novel “theology of the liturgical assembly,” who stated with reference to the priest’s power to consecrate the bread and wine:

“This does not mean that he can do it alone, that is, when he remains alone. He does not, in other words, consecrate the elements by virtue of a power which is inherent in him.” (7)

‘Active participation’ favors heresy

According to this “new theology,” which echoes Protestant perspectives, it is the “active participation” of the gathered assembly talking and singing together that makes Christ present in the Eucharist. Consequently, the doctrine that the words uttered by the priest at the Consecration are the unique cause of the Real Presence in the Mass is never made clear in the Novus Ordo Mass. It is obvious that the reformers wanted both the Real Presence and the priest’s unique role in effecting transubstantiation to be ignored and forgotten.

First communicants join the priest to participate at the Consecration, or ‘Institution Narrative’

Fr. Joseph Jungmann, who was no ordinary, run-of-the-mill liturgist ‒ he actually drafted some parts of the Liturgy Constitution ‒ favored this concept, as we can see from his description of the liturgies of the early Church:

“In the liturgical action the participation of the people was manifested especially by the fact that they did not merely listen to the prayers of the priest in silence but ratified them by their acclamations.” (9) [emphasis added]

Even the Canon of the Mass is not considered to be complete without the people’s Amen at the final Doxology. (10) Bugnini stated with reference to the Eucharistic Prayer: “They are to ratify with their ‘Amen’ what the priest has done and asked in the assembly’s name.” (11) [emphasis added]

The use of the term “ratify” as a necessary action on the part of the congregation is most illuminating. It reveals the intention of the reformers who devised the Novus Ordo Mass to embrace beliefs and practices not endorsed by the Church.

Pope Pius XII had specifically condemned those who “go so far as to hold that the people must confirm and ratify the Sacrifice if it is to have its proper force and value,” and added: “It is in no wise required that the people ratify what the sacred minister has done.” (Mediator Dei §§ 95-96)

Yet this was an indispensable requirement of the General Instruction, and was recognized as such by the English Bishops when they mentioned “the profound importance of the assembly’s ratification and acclamation” at the end of the Canon. (12)

Ratification, a term suggestive of heresy

The idea of the assembly’s “ratification” is doubly anomalous, a deviation not only from the millennial lex orandi, but also from the lex credendi. As a term borrowed from legal transactions, it gives the impression that the expressed consent of the people is necessary to make the Consecration officially valid, whereas its validity is ensured ex vi verborum, i.e., by virtue of the words of the priest alone.

The boot is on the other foot

The Sacrifice of Christ: ratified only by God in Heaven, not by the people on earth

But that reversal was precisely the objective of the Liturgical Movement.

Usurping God's authority

It is God Who is meant to ratify the Sacrifice of His Son, as is made clear in the Quam oblationem of the Canon, where the priest requests God to ratify (“ratam facere”) the Sacrifice he is about to offer in persona Christi.

As Dom Guéranger explained: “It must needs be ratified, approved, confirmed in Heaven, as a Thing most truly Good and Fitting. (13)

But then, as the evidence overwhelmingly shows, the Novus Ordo Mass was always a man-centred liturgy in which the People of God take centre stage.

Continued

- Celebrating the Mass: A Pastoral Introduction, April 2005, Catholic Bishops’ Conference of England and Wales, p. 17.

- The term “Levite” can cause confusion because, whereas all Old Testament priests from the time of Aaron were Levites, not all Levites were priests. It is generally used to identify the part of the tribe of Levi that was appointed for Tabernacle service and to be servants and helpers of the only authorized priests of Israel, the male descendants of Aaron. Both priest and Levite are mentioned in the parable of the Good Samaritan.

- Pope Pius X, Motu proprio Tra le Sollecitudini, 1903, (§12)

- Canon 107 (1917 Code of Canon Law) states: “Ex divina insitutione sunt in Ecclesia clerici a laicis distincti”. (By divine institution there are in the Church clerics distinct from the laity)

- Frederick McManus, The Rites of Holy Week: Ceremonies, Preparation, Music, Commentaries, Paterson, NJ: St. Anthony Guild Press, 1956, p. 32.

- Pius XII was the first Pope to use this phrase. See De Musica Sacra, 1958, § 31. This document, as we have seen, designates the whole of the Ordinary and the Propers as the “people’s parts.” In the Novus Ordo Mass, some priests omit the Sanctus and the Agnus Dei if the congregation remains silent, while others refuse to proceed with the Mass if no one is willing to bring up the gifts at the Offertory.

- Yves Congar, Je Crois en l’Esprit Saint, vol. 3, Paris, Cerf, 1980, p. 305.

- The General Instruction states that the dialogue between the priest and the assembled faithful is necessary “in every form of the Mass, so that the action of the whole community may be clearly expressed and fostered”. (§35)

- Joseph Jungmann, S.J., Mass of the Roman Rite, vol. 1, p. 236.

- The General Instruction also states that the final part of the Eucharistic Prayer is “affirmed and concluded by the people’s Amen.”.(§79h)

- A. Bugnini, The Reform of the Liturgy 1948-1975, Liturgical Press, 1990.

- Celebrating the Mass: A Pastoral Introduction, April 2005, Catholic Bishops’ Conference of England and Wales, p. 87.

- Dom Prosper Guéranger, Explanation of the Prayers and Ceremonies of the Holy Mass, translated from the French by Dom Laurence Shepherd, Monk of the English Benedictine Congregation, Stanbrook:St. Mary’s Abbey, 1885

Posted November 2, 2018

______________________

______________________

Volume I |

Volume II |

Volume III |

Volume IV |

Volume V |

Volume VI |

Volume VII |

Volume VIII |

Volume IX |

Volume X |

Volume XI |

Special Edition |