Traditionalist Issues

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Dialogue Mass - CVI

Not the Whole Truth or even Half of It

How much credibility ought we to accord the research conducted by the Consilium’s Committee on the Minor Orders, given the partisan profile of its members? And what are we to make of the studies produced under the guise of scholarly and academic research by the erudite members of the Committee for the abolition of the Minor clerical Orders?

Surely this monumental clash between the Titans of the Liturgical Movement who sought control of the liturgy, and the millennial Tradition of the Church should raise at least some eyebrows if not some hackles. Their work was music to the ears of reforming zealots of their day; it impressed Paul VI (his Ministeria quaedam was cobbled together using whole chunks of texts, complete with identical language, lifted from their findings); and it continues to influence progressivists today.

Surely this monumental clash between the Titans of the Liturgical Movement who sought control of the liturgy, and the millennial Tradition of the Church should raise at least some eyebrows if not some hackles. Their work was music to the ears of reforming zealots of their day; it impressed Paul VI (his Ministeria quaedam was cobbled together using whole chunks of texts, complete with identical language, lifted from their findings); and it continues to influence progressivists today.

But raw data on their own serve little purpose; they need the essential qualities of reason, context and a commitment to truth when being applied to historical circumstances. The following examination of the Committee’s methodology will reveal the extent to which these salutary influences were lacking and how, as a consequence, the Committee distinguished itself as a Think Tank that delivered an unreliable and sloppy analysis of the role of Minor Orders in the History of the Church.

The research findings provided by the reformers were skewed to deliver a certain message: that the Minor Orders were unsustainable as steps to the priesthood because they were merely “empty titles, contrary to the principle of ‘truthfulness’ that is to be followed in the liturgical reform,” (1) and, therefore, no longer corresponded to a “real situation” in the Church.

Lack of commitment to objective reality

How did they arrive at this damning conclusion? They put their own “spin” on the history of the Minor Orders, making sweeping generalizations, exaggerating or oversimplifying the evidence. Their reasoning went something like this: But these are neither serious nor intellectually respectable arguments upon which to make a coherent case for the abolition of Minor Orders. No attempt was made to define the term “real” – it was vaguely linked to “how people think nowadays” – or to address the supernatural reality of the offices. Even the claim of “truthfulness” became a catalyst for doing away with fidelity to the truthfulness of Tradition.

But these are neither serious nor intellectually respectable arguments upon which to make a coherent case for the abolition of Minor Orders. No attempt was made to define the term “real” – it was vaguely linked to “how people think nowadays” – or to address the supernatural reality of the offices. Even the claim of “truthfulness” became a catalyst for doing away with fidelity to the truthfulness of Tradition.

Let us see how this worked out in practice by analyzing the Committee’s research findings, (see Part 105) with special reference to Fr. Joseph Lécuyer’s contributions. For anyone who still believes that the reforms were divinely inspired (as the reformers themselves claimed) and characterized by the inerrancy of Holy Writ, this analysis should dispel that misapprehension.

Minor Orders as steps to the priesthood

This was the main bone of contention with the reformers whose aim was to convince the faithful that the various offices performed by minor clerics in the past were not inherently clerical in nature, but belonged by right to the “priesthood of all the baptized.”

So they set out to sever the historic connection between the minor ecclesiastical offices and the clerical status of their tonsured holders. Their revolutionary wish was fully granted in Paul VI’s Ministeria quaedam.

Fr. Lécuyer’s ‘think piece’

In 1970, Fr. Lécuyer, representing the Consilium’s Committee, published a long article in a progressivist French journal (2) to justify the impending suppression of the Minor Orders. But, as we shall see, he failed to provide one solid reason why they should be abolished, for there is no direct logical link between what he said and what he hoped to achieve.

His article consisted in a collection of statements that supported Vatican II’s new-found emphasis on the “priesthood of the baptized” as a basis for lay “active participation.” However, in promoting this stepping-stone to greater freedom for the laity, he overlooked the immovable stumbling block of Tradition that had consecrated the offices of the Minor Orders from the beginning as essentially clerical in nature.

His article consisted in a collection of statements that supported Vatican II’s new-found emphasis on the “priesthood of the baptized” as a basis for lay “active participation.” However, in promoting this stepping-stone to greater freedom for the laity, he overlooked the immovable stumbling block of Tradition that had consecrated the offices of the Minor Orders from the beginning as essentially clerical in nature.

Take, for instance, his statement that the reform was justified because in former times the Minor Orders were not always seen as steps to the priesthood, and were sometimes conferred on men who had no intention of proceeding to the Diaconate. Without explaining the historical context, he concluded that the Minor Orders should be dispensed with and that permanent ministries should be established for lay people.

He omitted to mention that, in those days, when necessity arose, there were some who, out of humility and love for lowly tasks, willingly dedicated their lives to the duties of the Minor Orders in order to serve the deacons and priests, without themselves advancing to that higher status. There was no question of a free-for-all for lay activism, as Fr. Lécuyer would have us believe, which was later superseded by clerical domination.

It is, of course, an essential tool of propagandists to omit the crucial context because it simply does not fit in with the narrative they have decided to foist on their target audience. The reformers were keen to spread the false notion that the Minor Orders were originally performed by lay men and women. but that their roles were usurped by the clergy. By 1970, it was high time to redress the balance and “restore justice” to the laity.

Echoing Vatican II’s novel interpretation of the “priesthood of the faithful”, no one, Fr. Lécuyer said, had the right to exclude them from service at the altar, reading the Scriptures during the liturgy, forming an Offertory procession or distributing Holy Communion during Mass. He saw these innovations as a “sign of the purification of our Christian faith” in that they would rid the Church of “taboos” about touching certain things regarded as sacred, or exhibiting a reverential attitude in the liturgy redolent of the fear of God associated with former times. (3)

The ‘ordination principle’

But the Church before Vatican II has always been clear about the clerical nature of the Minor Orders even when it allowed laymen, where necessity demanded, to perform the duties of Porter or Acolyte. Nevertheless, it must be kept in mind that only the ordained had the right, in virtue of their ordination, to perform these duties, whereas the layman acted only by a favour granted to him by the Church.

Now that ordination to Minor Orders has been replaced by the “institution” of ministries for the laity, modern Catholics find it hard to understand how a priest can undertake the role of a minor cleric in the traditional rites without “usurping” lay roles in the sanctuary.

Even with Major Orders, they talk of the priest as “playing at being a deacon” or acting illogically as sub-deacon. The key to the misunderstanding is the word “ordination” which gives the priest the right to perform any of the roles, minor or major, to which he had been ordained – a right which, by definition, cannot apply to the laity. Only a revolution to turn the tables on the clergy would reverse these conditions, which is exactly what Ministeria quaedam achieved by enabling the laity to leapfrog juridically into offices reserved by right to ordained ministers.

Continued

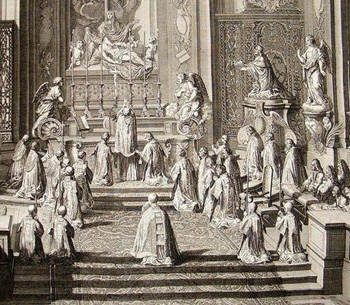

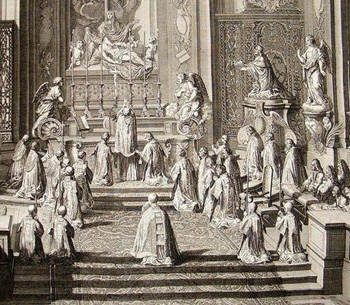

Each Order had a place and function before Vatican II

But raw data on their own serve little purpose; they need the essential qualities of reason, context and a commitment to truth when being applied to historical circumstances. The following examination of the Committee’s methodology will reveal the extent to which these salutary influences were lacking and how, as a consequence, the Committee distinguished itself as a Think Tank that delivered an unreliable and sloppy analysis of the role of Minor Orders in the History of the Church.

The research findings provided by the reformers were skewed to deliver a certain message: that the Minor Orders were unsustainable as steps to the priesthood because they were merely “empty titles, contrary to the principle of ‘truthfulness’ that is to be followed in the liturgical reform,” (1) and, therefore, no longer corresponded to a “real situation” in the Church.

Lack of commitment to objective reality

How did they arrive at this damning conclusion? They put their own “spin” on the history of the Minor Orders, making sweeping generalizations, exaggerating or oversimplifying the evidence. Their reasoning went something like this:

- The Doorkeeper no longer turned the key in the lock – so, clearly, he must be shown the door; and who needs Frère Jacques to ring the church bells when any layman can perform the task?;

- The Lector did not read the lessons at Mass – that role was performed before Vatican II by the priest and after Vatican II by the laity – he was obviously surplus to requirements, a real impediment to their “active participation”;

- The Exorcist was not allowed to cast out demons – so what was the point of his existence? He should be commanded to depart because modern man no longer believes in the existence of the Devil;

- The Acolyte would cease to serve at the altar as soon as he became a priest – such a short-lived role was not worth the candle, figuratively speaking.

- Minor Orders have become a useless formality – they had only been preserved out of routine and nostalgia for a bygone age;

- We must end the clerical status of these functions because lay people can perform them – the term “ordination” is absurd and should be changed to “institution”.

Door greeters at St. Francis of Assisi Church in Maryland

Let us see how this worked out in practice by analyzing the Committee’s research findings, (see Part 105) with special reference to Fr. Joseph Lécuyer’s contributions. For anyone who still believes that the reforms were divinely inspired (as the reformers themselves claimed) and characterized by the inerrancy of Holy Writ, this analysis should dispel that misapprehension.

Minor Orders as steps to the priesthood

This was the main bone of contention with the reformers whose aim was to convince the faithful that the various offices performed by minor clerics in the past were not inherently clerical in nature, but belonged by right to the “priesthood of all the baptized.”

So they set out to sever the historic connection between the minor ecclesiastical offices and the clerical status of their tonsured holders. Their revolutionary wish was fully granted in Paul VI’s Ministeria quaedam.

Fr. Lécuyer’s ‘think piece’

In 1970, Fr. Lécuyer, representing the Consilium’s Committee, published a long article in a progressivist French journal (2) to justify the impending suppression of the Minor Orders. But, as we shall see, he failed to provide one solid reason why they should be abolished, for there is no direct logical link between what he said and what he hoped to achieve.

Female lectors consider reading their 'right' today

Take, for instance, his statement that the reform was justified because in former times the Minor Orders were not always seen as steps to the priesthood, and were sometimes conferred on men who had no intention of proceeding to the Diaconate. Without explaining the historical context, he concluded that the Minor Orders should be dispensed with and that permanent ministries should be established for lay people.

He omitted to mention that, in those days, when necessity arose, there were some who, out of humility and love for lowly tasks, willingly dedicated their lives to the duties of the Minor Orders in order to serve the deacons and priests, without themselves advancing to that higher status. There was no question of a free-for-all for lay activism, as Fr. Lécuyer would have us believe, which was later superseded by clerical domination.

It is, of course, an essential tool of propagandists to omit the crucial context because it simply does not fit in with the narrative they have decided to foist on their target audience. The reformers were keen to spread the false notion that the Minor Orders were originally performed by lay men and women. but that their roles were usurped by the clergy. By 1970, it was high time to redress the balance and “restore justice” to the laity.

Echoing Vatican II’s novel interpretation of the “priesthood of the faithful”, no one, Fr. Lécuyer said, had the right to exclude them from service at the altar, reading the Scriptures during the liturgy, forming an Offertory procession or distributing Holy Communion during Mass. He saw these innovations as a “sign of the purification of our Christian faith” in that they would rid the Church of “taboos” about touching certain things regarded as sacred, or exhibiting a reverential attitude in the liturgy redolent of the fear of God associated with former times. (3)

The ‘ordination principle’

But the Church before Vatican II has always been clear about the clerical nature of the Minor Orders even when it allowed laymen, where necessity demanded, to perform the duties of Porter or Acolyte. Nevertheless, it must be kept in mind that only the ordained had the right, in virtue of their ordination, to perform these duties, whereas the layman acted only by a favour granted to him by the Church.

Now that ordination to Minor Orders has been replaced by the “institution” of ministries for the laity, modern Catholics find it hard to understand how a priest can undertake the role of a minor cleric in the traditional rites without “usurping” lay roles in the sanctuary.

Even with Major Orders, they talk of the priest as “playing at being a deacon” or acting illogically as sub-deacon. The key to the misunderstanding is the word “ordination” which gives the priest the right to perform any of the roles, minor or major, to which he had been ordained – a right which, by definition, cannot apply to the laity. Only a revolution to turn the tables on the clergy would reverse these conditions, which is exactly what Ministeria quaedam achieved by enabling the laity to leapfrog juridically into offices reserved by right to ordained ministers.

Continued

- A. Bugnini, The Reform of the Liturgy, p. 728

- ‘Les ordres mineurs en question’, La Maison-Dieu, vol. 102, 1970, pp. 97-107.

- Ibid., p. 100

Posted September 3 2021

______________________

______________________

Volume I |

Volume II |

Volume III |

Volume IV |

Volume V |

Volume VI |

Volume VII |

Volume VIII |

Volume IX |

Volume X |

Volume XI |

Special Edition |