Traditionalist Issues

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Dialogue Mass - CVIII

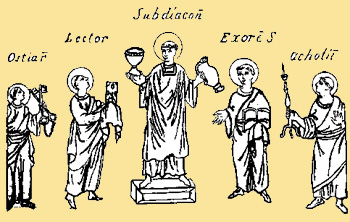

Why Should the Minor Orders

Be Accused of ‘Untruthfulness’?

This is a question that hardly any Novus Ordo priests today would be interested in asking, as most would assume that the Minor Orders had been suppressed for a very good reason. If asked, however, their inevitable reaction would be to dismiss the Minor Orders as an anachronism that had no place in the “age of the laity” – a statement that begs the question rather than supplying a rational explanation.

And if pressed further, the more radical among them would fall back on another circular argument found in Ministeria quaedam, which is that the Minor Orders did not fulfil the criteria for “truthfulness” as laid down by Fr. Bugnini and the Consilium. Here we may interject that their readiness, even enthusiasm, to be deceived by propaganda has been a major force in the success of the Vatican II reforms.

The source of this particular piece of propaganda was, as we have seen, the Consilium’s Committee which met in Livorno in 1965 when its members decided to accuse the Minor Orders of having lost any connection with “truthfulness.” In support of the Committee’s findings, Fr. Lécuyer wrote an article in 1970 denouncing the Minor Orders as an absurd anachronism with no discernible connection to real life situations.

In it, he argued that the Minor Orders had lost their character of “truthfulness,” and that it was Vatican II’s promotion of lay activism that supplied the antidote for this malaise. He assured his readers that even the seminarians of his time (who, we now know, were willing to swallow any amount of heretical propaganda) rejected them on the grounds of their alleged “untruthfulness.”

In it, he argued that the Minor Orders had lost their character of “truthfulness,” and that it was Vatican II’s promotion of lay activism that supplied the antidote for this malaise. He assured his readers that even the seminarians of his time (who, we now know, were willing to swallow any amount of heretical propaganda) rejected them on the grounds of their alleged “untruthfulness.”

It seems that when Fr. Lécuyer made this statement he had never ventured outside the Consilium’s echo chamber, or else had no sense of irony. For, the voices of opposition to Minor Orders had come mainly from those mutinous seminarians in the German-speaking countries who were unwilling to submit to ecclesiastical authority. Theirs was hardly a reliable testimony on which to assess the situation.

Besides, by then, all seminarians had been indoctrinated with the progressivist principles of Vatican II, which would dispose them against traditional seminary training. How could they hope to become priests unless they, too, rejected the Minor Orders in favor of the paramountcy of lay participation in the Church?

So what, then, were the “true perspectives” that Fr. Lécuyer had in mind and that the historic Church had failed to see? They were all about performing specific jobs “in the heart of the Christian community,” rather than being “directly ordered towards supporting the spiritual life of the future priest.” (1)

These words not only betray the crass literal-mindedness of his understanding of the Minor Orders as a jobs-to-be-done Training Workshop to set a common direction for “active participation” of all the faithful. But they also reveal his barely-concealed desire to re-orient the training of priests away from the traditional spirituality (requiring seminarians to be withdrawn from the world) which was designed to enhance their sanctification, that is, to make future “holy priests.”

This “utilitarian” conception of ministry stems from the progressivist notion that the priesthood is mainly about serving the community rather than the true priestly task of offering the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass to God. It was precisely on this issue that the reform departed from the teaching of the Council of Trent.

Kasper: Vatican II ‘corrected’ Trent

Card. Walter Kasper stated that “Luther certainly had reasons for his protest” against the concept of the priesthood canonized at Trent for being “excessively narrow and one-sided” in identifying it in terms of the Holy Sacrifice. He went on to state that “it was the achievement of the Second Vatican Council to present a holistic understanding that left behind the narrow reductionisms of the past.” (2)

A changed priesthood for a changing Church

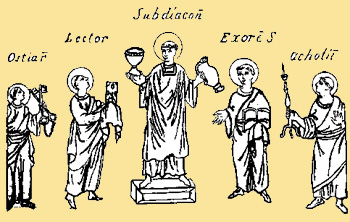

We now come to the nub of the question: the loss of the supernatural dimension of the priesthood. The Council of Trent described the Minor clerical Orders as an eminently fitting and proper (“consentaneum”) (3) preparation for ordination to the priesthood.

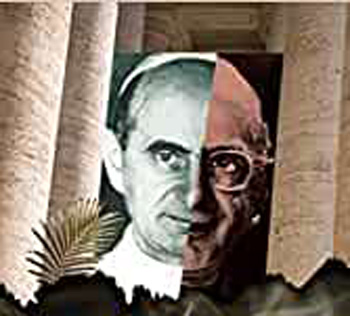

The 20th-century reformers’ assessment of the Minor Orders was, instead, undertaken in clearly naturalistic terms – their outlook was formed by Vatican II’s “openness to the world” and promotion of the laity. When Pope Paul VI declericalized the Minor Orders and replaced them by lay ministries, he did so, as he himself declared in Ministeria quaedam, in accordance with the Council’s principles that “active participation by all the people is the aim to be considered before all else.”

The 20th-century reformers’ assessment of the Minor Orders was, instead, undertaken in clearly naturalistic terms – their outlook was formed by Vatican II’s “openness to the world” and promotion of the laity. When Pope Paul VI declericalized the Minor Orders and replaced them by lay ministries, he did so, as he himself declared in Ministeria quaedam, in accordance with the Council’s principles that “active participation by all the people is the aim to be considered before all else.”

We gather from this that the loss of the Minor Orders – a matter that impinges on the very nature of the ordained priesthood – is regarded as of no importance whatever compared with the Council’s over-exaggerated mandate for the aggrandizement of the laity. It is obvious that their abolition and substitution by ministries exclusively exercised by lay people could not have derived from Tradition: a previous attempt to achieve this reform in the 18th century had already been condemned by Pope Pius VI as harmful to the Church. (4)

The inversion of truthfulness

Unfortunately, this anti-traditional view continues to be the received wisdom even today among the bien pensants of the liturgical establishment. The consensus of opinion in the Church is that the practice of the Minor Orders in preceding centuries, especially since the Council of Trent, was flawed in the sense of “untruthful,” utterly useless and absurd, even harmful to the good of the Church. But that is a self-contradictory and untenable position for any Catholic to hold because if what the reformers allege is true, then the Church would have to be false.

One would have thought that this onslaught against the holy institution of the Minor Orders would have been countered by a spirited resistance from the Catholic Hierarchy. But most Bishops being progressivists, instead of making strong protest as their duty would require, silently permitted them to be maligned in influential publications and even in the official documents of the Church.

The roots of schism

Let us keep in mind that when Paul VI abolished the Minor Orders and the Sub-Diaconate, he not only contradicted the truth of their status as clerical orders, but also rejected the anathemas issued by the Council of Trent on this subject. He inflicted on the Church a sudden and violent change that would prove to be severely damaging to the Faith.

Ministeria quaedam was a blow aimed directly at the traditional understanding of the hierarchical priesthood for which a gradation of clerical orders by way of preparation and probation – the so-called cursus honorum – had been understood to have existed from the very beginnings of the Church (ad ipso Ecclesiae initio, as the Council of Trent stated).

Ministeria quaedam was a blow aimed directly at the traditional understanding of the hierarchical priesthood for which a gradation of clerical orders by way of preparation and probation – the so-called cursus honorum – had been understood to have existed from the very beginnings of the Church (ad ipso Ecclesiae initio, as the Council of Trent stated).

When this long-standing tradition was abruptly ended in 1972, clergy and laity alike were left with the impression that what they believed about the greatness of the ordained priesthood was a monumental delusion that came crashing down at the stroke of a papal pen.

It is true that the sequence of Minor Orders had a varied and complex history before becoming standardized in the 11th century in the Western Church. (5) But what remained unchanged over all the centuries up to 1972 was the vital principle of stability and continuity insofar as they were recognized as clerical in nature. This was the unbroken Latin tradition as it was actually understood in the first two millennia of the Church. And as no Pope has the authority to subvert Tradition, we can draw the only reasonable conclusion that Ministeria quaedam – like many other of Pope Paul’s innovations, including his Novus Ordo Missae – was a schismatic act. (here, here and here)

This conclusion is strengthened by the open derision and contempt with which the Consilium members treated the Minor Orders and the slurs they cast on their truthfulness. It is scarcely credible that they could speak in those terms against an ancient and venerable institution that had supported their own priesthood.

This conclusion is strengthened by the open derision and contempt with which the Consilium members treated the Minor Orders and the slurs they cast on their truthfulness. It is scarcely credible that they could speak in those terms against an ancient and venerable institution that had supported their own priesthood.

How can Catholic priests so despise their own sacred tradition of Minor Orders as to recommend their abolition? How can a Pope accede to their demands, suddenly declare them to be outdated categories, and sever their intrinsic connection with the clerical state?

It is unconscionable that the Church was providing a platform for the dissemination of lies about the liturgy and that it was providing support for those who were hostile towards Tradition and anyone who followed it faithfully.

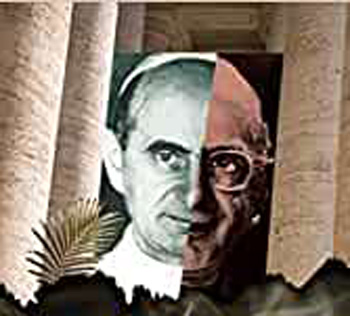

Pope Paul VI famously lamented that the Church was undergoing a process of self-demolition. But in a Church where the revolutionaries’ desires are more important than Tradition, and where the ordained ministers have been induced to hate what they had been taught to love before Vatican II, what other outcome could be expected?

Continued

And if pressed further, the more radical among them would fall back on another circular argument found in Ministeria quaedam, which is that the Minor Orders did not fulfil the criteria for “truthfulness” as laid down by Fr. Bugnini and the Consilium. Here we may interject that their readiness, even enthusiasm, to be deceived by propaganda has been a major force in the success of the Vatican II reforms.

The source of this particular piece of propaganda was, as we have seen, the Consilium’s Committee which met in Livorno in 1965 when its members decided to accuse the Minor Orders of having lost any connection with “truthfulness.” In support of the Committee’s findings, Fr. Lécuyer wrote an article in 1970 denouncing the Minor Orders as an absurd anachronism with no discernible connection to real life situations.

The Vatican II aim: Liberating the seminarians and ‘letting them’ enter into ‘real life’

It seems that when Fr. Lécuyer made this statement he had never ventured outside the Consilium’s echo chamber, or else had no sense of irony. For, the voices of opposition to Minor Orders had come mainly from those mutinous seminarians in the German-speaking countries who were unwilling to submit to ecclesiastical authority. Theirs was hardly a reliable testimony on which to assess the situation.

Besides, by then, all seminarians had been indoctrinated with the progressivist principles of Vatican II, which would dispose them against traditional seminary training. How could they hope to become priests unless they, too, rejected the Minor Orders in favor of the paramountcy of lay participation in the Church?

So what, then, were the “true perspectives” that Fr. Lécuyer had in mind and that the historic Church had failed to see? They were all about performing specific jobs “in the heart of the Christian community,” rather than being “directly ordered towards supporting the spiritual life of the future priest.” (1)

These words not only betray the crass literal-mindedness of his understanding of the Minor Orders as a jobs-to-be-done Training Workshop to set a common direction for “active participation” of all the faithful. But they also reveal his barely-concealed desire to re-orient the training of priests away from the traditional spirituality (requiring seminarians to be withdrawn from the world) which was designed to enhance their sanctification, that is, to make future “holy priests.”

This “utilitarian” conception of ministry stems from the progressivist notion that the priesthood is mainly about serving the community rather than the true priestly task of offering the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass to God. It was precisely on this issue that the reform departed from the teaching of the Council of Trent.

Kasper: Vatican II ‘corrected’ Trent

Card. Walter Kasper stated that “Luther certainly had reasons for his protest” against the concept of the priesthood canonized at Trent for being “excessively narrow and one-sided” in identifying it in terms of the Holy Sacrifice. He went on to state that “it was the achievement of the Second Vatican Council to present a holistic understanding that left behind the narrow reductionisms of the past.” (2)

A changed priesthood for a changing Church

We now come to the nub of the question: the loss of the supernatural dimension of the priesthood. The Council of Trent described the Minor clerical Orders as an eminently fitting and proper (“consentaneum”) (3) preparation for ordination to the priesthood.

Pius VI condemned a similar attempt

to reform the priesthood

We gather from this that the loss of the Minor Orders – a matter that impinges on the very nature of the ordained priesthood – is regarded as of no importance whatever compared with the Council’s over-exaggerated mandate for the aggrandizement of the laity. It is obvious that their abolition and substitution by ministries exclusively exercised by lay people could not have derived from Tradition: a previous attempt to achieve this reform in the 18th century had already been condemned by Pope Pius VI as harmful to the Church. (4)

The inversion of truthfulness

Unfortunately, this anti-traditional view continues to be the received wisdom even today among the bien pensants of the liturgical establishment. The consensus of opinion in the Church is that the practice of the Minor Orders in preceding centuries, especially since the Council of Trent, was flawed in the sense of “untruthful,” utterly useless and absurd, even harmful to the good of the Church. But that is a self-contradictory and untenable position for any Catholic to hold because if what the reformers allege is true, then the Church would have to be false.

One would have thought that this onslaught against the holy institution of the Minor Orders would have been countered by a spirited resistance from the Catholic Hierarchy. But most Bishops being progressivists, instead of making strong protest as their duty would require, silently permitted them to be maligned in influential publications and even in the official documents of the Church.

The roots of schism

Let us keep in mind that when Paul VI abolished the Minor Orders and the Sub-Diaconate, he not only contradicted the truth of their status as clerical orders, but also rejected the anathemas issued by the Council of Trent on this subject. He inflicted on the Church a sudden and violent change that would prove to be severely damaging to the Faith.

A death blow to the cursus honorum

When this long-standing tradition was abruptly ended in 1972, clergy and laity alike were left with the impression that what they believed about the greatness of the ordained priesthood was a monumental delusion that came crashing down at the stroke of a papal pen.

It is true that the sequence of Minor Orders had a varied and complex history before becoming standardized in the 11th century in the Western Church. (5) But what remained unchanged over all the centuries up to 1972 was the vital principle of stability and continuity insofar as they were recognized as clerical in nature. This was the unbroken Latin tradition as it was actually understood in the first two millennia of the Church. And as no Pope has the authority to subvert Tradition, we can draw the only reasonable conclusion that Ministeria quaedam – like many other of Pope Paul’s innovations, including his Novus Ordo Missae – was a schismatic act. (here, here and here)

Paul VI lamented the self-demolition he promoted

How can Catholic priests so despise their own sacred tradition of Minor Orders as to recommend their abolition? How can a Pope accede to their demands, suddenly declare them to be outdated categories, and sever their intrinsic connection with the clerical state?

It is unconscionable that the Church was providing a platform for the dissemination of lies about the liturgy and that it was providing support for those who were hostile towards Tradition and anyone who followed it faithfully.

Pope Paul VI famously lamented that the Church was undergoing a process of self-demolition. But in a Church where the revolutionaries’ desires are more important than Tradition, and where the ordained ministers have been induced to hate what they had been taught to love before Vatican II, what other outcome could be expected?

Continued

- E. Lécuyer, ‘Les ordres mineurs en question,’ La Maison-Dieu, vol. 102, 1970, p. 99.

- Walter Kasper, A Celebration of Priestly Ministry, New York: Crossroads, 2007, p. 156.

- Session XXIII, Canon II.

- Pope Pius VI, in his Constitution Auctorem Fidei, 1794, had already condemned the proposal to remove the lesser clergy and give their function to lay people as “a rash suggestion, offensive to pious ears, disturbing to the ecclesiastical ministry, lessening of the decency which should he observed as far as possible in celebrating the mysteries, injurious to the duties and functions of minor orders, as well as to the discipline approved by the canons and especially by the Tridentine Synod, favorable to the charges and calumnies of heretics against it.”

- John St. H. Gibaut, The Cursus Honorum: A Study of Origins and Evolution of Sequential Ordination, Patristic Studies, vol. 3, Bern: Peter Lang, 2000, p. 247.

Posted October 18, 2021

______________________

______________________

Volume I |

Volume II |

Volume III |

Volume IV |

Volume V |

Volume VI |

Volume VII |

Volume VIII |

Volume IX |

Volume X |

Volume XI |

Special Edition |