Traditionalist Issues

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Dialogue Mass - CV

Confused Papal Text Led to the End

of Minor Orders

If we pause for a moment to take stock of the situation with the Minor Orders in the years immediately after Vatican II, one inescapable point stands out: The liturgical reformers enjoyed excessive and unfair advantages over traditionalists.

We have seen how Bishops of the German-speaking countrieswho were the leading advocates of the Liturgical Movement (here, here, here and here) were also the most powerful lobbyists for the reform of the Minor Orders. It goes without saying that mutinous clerics in their dioceses were immune from disciplinary action and were effectively given a free pass to overthrow liturgical traditions.

Traditionally-minded clergy from around the world, on the other hand, who wanted to retain the Minor Orders and were not part of the fractious club of progressivists, remained outliers with severely limited, if any, influence.

Traditionally-minded clergy from around the world, on the other hand, who wanted to retain the Minor Orders and were not part of the fractious club of progressivists, remained outliers with severely limited, if any, influence.

This is clear from Bugnini's allusion to what he called unwelcome “external pressures” from high-ranking Prelates such as Cardinal Ottaviani who tried unsuccessfully to prevent the planned suppression of the Minor Orders and Sub-Diaconate. (1) Their opinions were completely ignored.

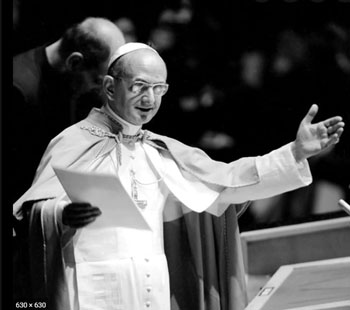

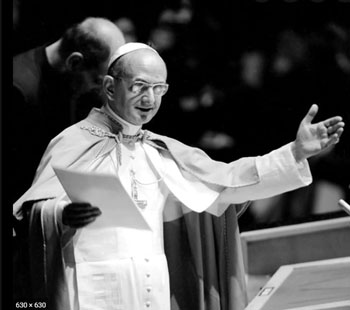

But, most importantly, the progressivists had the support of the Supreme Pontiff himself who, despite shedding a few tears over the impending demise of the Minor Orders, in the end did precisely nothing to save them.

Have cake, eat cake: the politics of ambivalence

Pope Paul VI wrote in 1967: “Minor orders must be retained, but their concept and function must be developed,” adding that they must be conferred in new and “improved rites.” (2)

Did these words denote retention or revolution? It seems that the Pope’s mind was conflicted about two mutually exclusive events: keeping the Minor Orders and simultaneously abolishing them, allowing them to exist and at the same time making them develop into something essentially different.

We are told that the Minor Orders were somehow ripe for “development” – a euphemism for their replacement by something “better,” and a veiled insult to the judgement of all his Predecessors throughout History who had upheld Tradition. When, however, we parse the issues underlying the rhetoric, we can see that nothing of substance has, in fact, been said.

We are told that the Minor Orders were somehow ripe for “development” – a euphemism for their replacement by something “better,” and a veiled insult to the judgement of all his Predecessors throughout History who had upheld Tradition. When, however, we parse the issues underlying the rhetoric, we can see that nothing of substance has, in fact, been said.

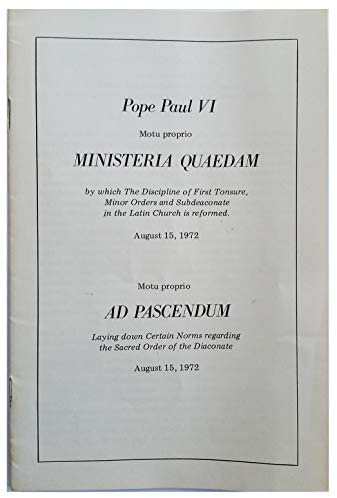

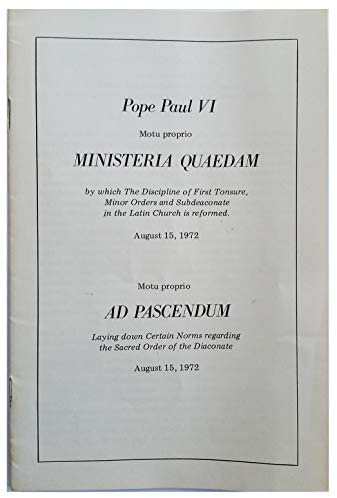

It was only when the crucial moment came in 1972 that the Pope revealed exactly what the new “concept and function” of the Minor Orders would develop into: liturgical activism for lay people, a distortion and falsification of their true vocation in the world.

Pope Paul VI tried to reassure the faithful with this bromide:

“This arrangement will bring out more clearly the distinction between clergy and laity, between what is proper and reserved to the clergy and what can be entrusted to the laity.”

But Ministeria quaedam mixed all the ingredients for the doctrinal confusion as to the identity of priests and lay people that is a hallmark of the post-conciliar Church.

This particular recipe for fudge leaves a bad taste in the mouth, for the revolutionary change could not be brought about without a betrayal of the historic Church, which had appreciated their enduring value in the spiritual formation of priests. This betrayal was the logical outcome of the “active participation” of the laity mandated by Vatican II, which Pope Paul VI endorsed to the hilt.

But fudge cannot hide the hard truth that the Pope, whose primary responsibility was to preserve Tradition and resist novelties, had collaborated with those who wanted to deprive the Church of bi-millennial Minor Orders. Whatever Paul VI’s personal feelings on the matter might have been, the fact remains that he was prepared to delegate his responsibility to a committee of “experts” and leave the fate of the Minor Orders in the hands of those who wanted rid of them.

A preset agenda

Bugnini relates the origin and formation of this committee as follows:

“At the fifth general meeting of the Consilium in April 1965, the Fathers expressed their wish that the problems raised by minor orders be studied in a limited group.” (3)

“At the fifth general meeting of the Consilium in April 1965, the Fathers expressed their wish that the problems raised by minor orders be studied in a limited group.” (3)

Even before the committee sat, we can see the presence of bias that would pre-determine the outcome: the study of the Minor Orders was framed in purely negative terms as a “problem” to be removed.

But it was a problem of Vatican II’s own making, because Minor clerical Orders could not coexist with the Council’s mandate to raise “active participation” of the laity to the highest priority. The fabricated problem could only be solved by the rejection of the tradition handed down and observed in the Roman Rite for centuries.

As for the members of the select group, we shall see from their credentials that all had divided loyalties over the best interests of the Church: whether to adhere to Tradition or follow the revolutionary agenda of Vatican II.

When it came to choosing sides, they took their stand against centuries of tradition and voted overwhelmingly that “those entering the diaconate should not be obliged to receive each and all of the minor orders” and that “laymen should be allowed to receive the minor orders” [without thereby becoming clerics]. (4)

The committee, held between July 1 and 3, 1965, was composed of the following members and consultors:

Msgr. Emilio Guano, Bishop of Livorno (President)

As a member of the Consilium, Bishop Guano collaborated in the reform of the rites of Ordination, both Major and Minor. He hosted the committee’s meetings on Minor Orders at his residential palace in Livorno.

As a member of the Consilium, Bishop Guano collaborated in the reform of the rites of Ordination, both Major and Minor. He hosted the committee’s meetings on Minor Orders at his residential palace in Livorno.

As he had spent his entire ecclesiastical career in promoting lay “empowerment” in the political sphere (5) as well as in the liturgy, his personal stake in the proceedings against the Minor Orders as exclusively clerical functions was thus already well established.

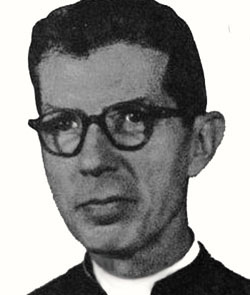

Dom Bernard Botte, OSB (Chairman)

Dom Bernard, a monk of Mont César was, together with his confrere, Lambert Beauduin, the inspiration behind the statement in Sacrosanctum Concilium that efforts to reform the liturgy would not succeed without a different type of formation of priests – hence his virulent attack on the Minor Orders, which he considered unfit for purpose.

He was given the chief responsibility for reforming the Roman Pontifical. Despite his reputation as a liturgical scholar of renown, no one could reasonably consider him to be an impartial source of information on the Pontifical which, he charged, had “seriously deviated from the true tradition” and required, therefore, a radical reform. (6)

The other group members who collaborated with him against the Minor Orders were Frs. Joseph Lécuyer, CSSP, (7) Aimé-Georges Martimort, (8) Emil Lengeling, (9) Cipriano Vagaggini, OSB Cam., (10) and Bruno Kleinheyer. (11) All were members of Coetus 20 of the Consilium for the reform of Holy Orders.

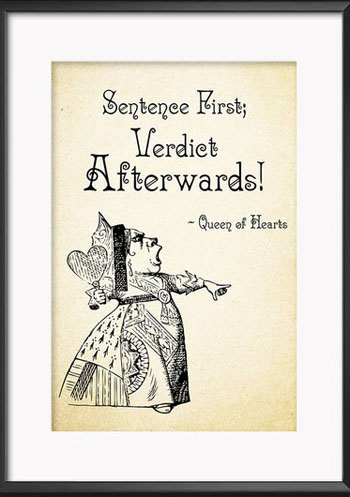

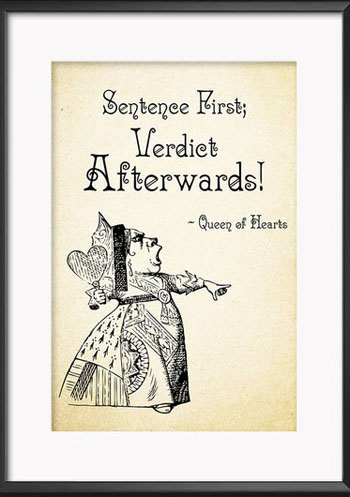

‘Sentence first, verdict afterwards’

These words, taken from Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland – the surreal world where people “believe in impossible things” – illustrate perfectly the essence of the treatment meted out to the Minor Orders.

As we have seen, the Minor Orders were placed on trial by an impromptu court set up at Livorno, whose members sat in judgement on the venerable rites, and declared them guilty of “irrelevance” to the modern age – a crime against aggiornamento for which the sentence was a foregone conclusion.

As we have seen, the Minor Orders were placed on trial by an impromptu court set up at Livorno, whose members sat in judgement on the venerable rites, and declared them guilty of “irrelevance” to the modern age – a crime against aggiornamento for which the sentence was a foregone conclusion.

Bugnini commented with evident satisfaction: “When we look back across the years to the work done at Livorno … we can see that it contained all or almost all of the elements needed for solutions reached only eight years later.” (12)

This is tantamount to admitting that the sentence against clerical Minor Orders had been assured years in advance of their formal suppression in 1972. When Pope Paul gave his verdict in Ministeria quaedam, he justified his decision by regurgitating point by point the arguments for the supposed “uselessness” of clerical Minor Orders, which had been put forward by the Livorno group in 1965.

We know that was the case from two sources. First, Bugnini recorded a list of the committee members’ objections:

Significantly, all of these points, sometimes couched in exactly the same phraseology, occur in Ministeria quaedam, as if the document had been ghost-written by Fr. Lécuyer.

In other words, it was merely a question of the Pope rubber-stamping the sentence against the Minor Orders passed by a small coterie of prejudiced naysayers who had been “primed” to respond negatively – their comments were a clear declaration of intent to have the Minor Orders declericalized.

It was the crowning achievement of the Liturgical Movement whose principal aim was to bring about a structural revolution, which would enable the laity juridically to take over functions reserved to the clergy.

Continued

We have seen how Bishops of the German-speaking countrieswho were the leading advocates of the Liturgical Movement (here, here, here and here) were also the most powerful lobbyists for the reform of the Minor Orders. It goes without saying that mutinous clerics in their dioceses were immune from disciplinary action and were effectively given a free pass to overthrow liturgical traditions.

Paul VI: ‘Minor Orders ripe for development’

This is clear from Bugnini's allusion to what he called unwelcome “external pressures” from high-ranking Prelates such as Cardinal Ottaviani who tried unsuccessfully to prevent the planned suppression of the Minor Orders and Sub-Diaconate. (1) Their opinions were completely ignored.

But, most importantly, the progressivists had the support of the Supreme Pontiff himself who, despite shedding a few tears over the impending demise of the Minor Orders, in the end did precisely nothing to save them.

Have cake, eat cake: the politics of ambivalence

Pope Paul VI wrote in 1967: “Minor orders must be retained, but their concept and function must be developed,” adding that they must be conferred in new and “improved rites.” (2)

Did these words denote retention or revolution? It seems that the Pope’s mind was conflicted about two mutually exclusive events: keeping the Minor Orders and simultaneously abolishing them, allowing them to exist and at the same time making them develop into something essentially different.

All the ingredients for doctrinal confusion

It was only when the crucial moment came in 1972 that the Pope revealed exactly what the new “concept and function” of the Minor Orders would develop into: liturgical activism for lay people, a distortion and falsification of their true vocation in the world.

Pope Paul VI tried to reassure the faithful with this bromide:

“This arrangement will bring out more clearly the distinction between clergy and laity, between what is proper and reserved to the clergy and what can be entrusted to the laity.”

But Ministeria quaedam mixed all the ingredients for the doctrinal confusion as to the identity of priests and lay people that is a hallmark of the post-conciliar Church.

This particular recipe for fudge leaves a bad taste in the mouth, for the revolutionary change could not be brought about without a betrayal of the historic Church, which had appreciated their enduring value in the spiritual formation of priests. This betrayal was the logical outcome of the “active participation” of the laity mandated by Vatican II, which Pope Paul VI endorsed to the hilt.

But fudge cannot hide the hard truth that the Pope, whose primary responsibility was to preserve Tradition and resist novelties, had collaborated with those who wanted to deprive the Church of bi-millennial Minor Orders. Whatever Paul VI’s personal feelings on the matter might have been, the fact remains that he was prepared to delegate his responsibility to a committee of “experts” and leave the fate of the Minor Orders in the hands of those who wanted rid of them.

A preset agenda

Bugnini relates the origin and formation of this committee as follows:

Former ‘minor orders’ of lector & acolyte

to both lay men & womenm

Even before the committee sat, we can see the presence of bias that would pre-determine the outcome: the study of the Minor Orders was framed in purely negative terms as a “problem” to be removed.

But it was a problem of Vatican II’s own making, because Minor clerical Orders could not coexist with the Council’s mandate to raise “active participation” of the laity to the highest priority. The fabricated problem could only be solved by the rejection of the tradition handed down and observed in the Roman Rite for centuries.

As for the members of the select group, we shall see from their credentials that all had divided loyalties over the best interests of the Church: whether to adhere to Tradition or follow the revolutionary agenda of Vatican II.

When it came to choosing sides, they took their stand against centuries of tradition and voted overwhelmingly that “those entering the diaconate should not be obliged to receive each and all of the minor orders” and that “laymen should be allowed to receive the minor orders” [without thereby becoming clerics]. (4)

The committee, held between July 1 and 3, 1965, was composed of the following members and consultors:

Msgr. Emilio Guano, Bishop of Livorno (President)

Bishop Guano, promoter of ‘lay empowerment’

As he had spent his entire ecclesiastical career in promoting lay “empowerment” in the political sphere (5) as well as in the liturgy, his personal stake in the proceedings against the Minor Orders as exclusively clerical functions was thus already well established.

Dom Bernard Botte, OSB (Chairman)

Dom Bernard, a monk of Mont César was, together with his confrere, Lambert Beauduin, the inspiration behind the statement in Sacrosanctum Concilium that efforts to reform the liturgy would not succeed without a different type of formation of priests – hence his virulent attack on the Minor Orders, which he considered unfit for purpose.

He was given the chief responsibility for reforming the Roman Pontifical. Despite his reputation as a liturgical scholar of renown, no one could reasonably consider him to be an impartial source of information on the Pontifical which, he charged, had “seriously deviated from the true tradition” and required, therefore, a radical reform. (6)

The other group members who collaborated with him against the Minor Orders were Frs. Joseph Lécuyer, CSSP, (7) Aimé-Georges Martimort, (8) Emil Lengeling, (9) Cipriano Vagaggini, OSB Cam., (10) and Bruno Kleinheyer. (11) All were members of Coetus 20 of the Consilium for the reform of Holy Orders.

‘Sentence first, verdict afterwards’

These words, taken from Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland – the surreal world where people “believe in impossible things” – illustrate perfectly the essence of the treatment meted out to the Minor Orders.

A scene from Alice in Wonderland...

Bugnini commented with evident satisfaction: “When we look back across the years to the work done at Livorno … we can see that it contained all or almost all of the elements needed for solutions reached only eight years later.” (12)

This is tantamount to admitting that the sentence against clerical Minor Orders had been assured years in advance of their formal suppression in 1972. When Pope Paul gave his verdict in Ministeria quaedam, he justified his decision by regurgitating point by point the arguments for the supposed “uselessness” of clerical Minor Orders, which had been put forward by the Livorno group in 1965.

We know that was the case from two sources. First, Bugnini recorded a list of the committee members’ objections:

- Minor Orders as steps to the priesthood no longer corresponded to a ‘real situation’;

- They have been, especially since Vatican II, routinely exercised by lay people;

- We must “meet the needs of the present-day Church” and open Minor Orders to the laity [i.e. end the clerical status of these functions];

- The canonical requirement to receive all the Minor Orders before entry to the Diaconate should be revoked;

- The term “ordination” should be changed to “institution”;

- The number of Minor Orders has varied in different periods of History and in the Churches of the East and West: they are not, therefore, immutable. (13)

Significantly, all of these points, sometimes couched in exactly the same phraseology, occur in Ministeria quaedam, as if the document had been ghost-written by Fr. Lécuyer.

In other words, it was merely a question of the Pope rubber-stamping the sentence against the Minor Orders passed by a small coterie of prejudiced naysayers who had been “primed” to respond negatively – their comments were a clear declaration of intent to have the Minor Orders declericalized.

It was the crowning achievement of the Liturgical Movement whose principal aim was to bring about a structural revolution, which would enable the laity juridically to take over functions reserved to the clergy.

Continued

- Annibale Bugnini, The Reform of the Liturgy 1948-1975, p. 745, note 28.

- Ibid., p. 737.

- Ibid., p. 727.

- Ibid., p. 734.

- First as one of Msgr. Montini’s successors as National Chaplain of the Italian Federation of University Students (FUCI) and then as the International Chaplain of Pax Romana. Bishop Guano was also Chairman of the mixed commission for Gaudium et spes, having been appointed by Paul VI to the Commission for the Laity, he played a key role in drafting Apostolicam actuositatem Vatican II’s Decree on the Apostolate of the Laity.

- B. Botte, ‘L'ordination de l'évêque’, La Maison-Dieu, vol. 98, n. 2, 1969, p. 115: “On ne pouvait pas advantage considérer le Pontifical romain comme un monument intangible qu’un cérémoniaire du 13e siècle aurait amené à sa perfection. L’étude de la tradition antérieure montrait d’ailleurs que, sur bien des points, on avait dévié de la vraie tradition. On ne pouvait donc pas se contenter d’une révision superficielle du texte”. (One could no longer consider the Roman Pontifical as an untouchable monument which a 13th-century papal master of ceremonies had brought to its state of perfection. Research into the former tradition, moreover, showed that, on many points, the Church had deviated from the true tradition. We cannot, therefore, be content with a superficial revision of the text).

- Professor at the Regina Mundi Pontifical Institute in Rome for the education of women religious.

- Professor of Liturgy at the Faculty of Theology, Toulouse, co-founder of the Centre de Pastorale Liturgique in Paris.

- Professor of Liturgical Studies at the University of Münster.

- Professor of Theology at the Pontifical Athenaeum of Sant'Anselmo in Rome, and a member of the Theological Commission. His argument for the sacramental ordination of women deacons was published as: ‘L’ordinazione delle diaconesse nella tradizione greca e bizantina,’ in Orientalia Christiana Periodica, vol. 40, 1974, pp. 145-189.

- Professor of Liturgical Science in 1968 at the Catholic Theological Faculty of the University of Regensburg, an advisor to the Liturgy Commission of the German Bishops’ Conference and a member of the Liturgical Commission of the Diocese of Regensburg.

- A. Bugnini, The Reform of the Liturgy, p. 730.

- Ibid., p. 728.

- J. Lécuyer, ‘Les ordres mineurs en question,’ La Maison-Dieu, vol. 102, 1970, pp. 97-107.

Posted August 2, 2021

______________________

______________________

Volume I |

Volume II |

Volume III |

Volume IV |

Volume V |

Volume VI |

Volume VII |

Volume VIII |

Volume IX |

Volume X |

Volume XI |

Special Edition |