Traditionalist Issues

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Dialogue Mass - II

Pius X Did Not Call for

‘Active Participation’ in Liturgy

Discrepancies between the Latin and vernacular texts of TLS

In the last article we pointed out discrepancies between the Italian and Latin versions of Pope Pius X’s motu proprio, Tra le Sollecitudini (TLS), mentioning that the word “active” had been added to the Italian text to describe the participation of the laity.

Here we shall deal more closely with the Italian version of TLS published in the Acta Sanctae Sedis in relation to the authentic Latin text and show how, on the crucial issue of the participation of the faithful in the liturgy, they diverge in meaning. Clearly, they cannot both represent the mind of the Pope.

Here we shall deal more closely with the Italian version of TLS published in the Acta Sanctae Sedis in relation to the authentic Latin text and show how, on the crucial issue of the participation of the faithful in the liturgy, they diverge in meaning. Clearly, they cannot both represent the mind of the Pope.

Let us examine § 3 of the Latin version, which indicates Pope Pius X’s intentions. It says in a few succinct words that Gregorian Chant, transmitted by tradition, is to be fully restored to the sacred rites: Cantus gregorianus, quem transmisit traditio, in sacris solemnibus omnino est instaurandus.

It then goes on to explain why Gregorian Chant should be given back to the people, so that in particular the Christian faithful may once again, in the custom of their forebears, participate more ardently in the liturgy: Praesertim apud populum cantus gregorianus est instaurandus, quo vehementius Christicolae, more maiorum, sacrae liturgiae sint rursus participes.

Now, we shall examine the pitfalls of having a document in the vernacular (both Italian and English) and the misconceptions that can arise because of faulty translations.

“By the people”

TLS says that Gregorian Chant should be restored nell'uso del popolo (for the use of the people) in the liturgy. It does not specify which people or for what purpose – singing or listening – they are to use the Chant. Even worse, the English version states that the use of Gregorian Chant by the people is what the Pope intended. The underlying suggestion made by these vague and generalized paraphrases is that “the people” means the whole congregation and that the Pope wanted them all to join in the Chant.

But that is an assumption that is not supported by the Latin text, which states that Gregorian Chant is to be restored apud populum, i.e., among or in the presence of the faithful; in other words, in the churches. The Pope had already expressed this idea in his Introduction: ubi Christicolae congregantur (there where the Christian faithful gather).

Apud is a preposition that indicates proximity or geographical location and cannot be translated by a phrase indicating instrumentality, as in something done “by the people.” In saying that Gregorian Chant should be restored to the people, the Pope gave no indication in this passage or elsewhere in the document that he wanted it to be sung by all the faithful.

“Active participation”

The problem revolves around the interpretation of “participation” of the laity in the liturgy as understood by Pope Pius X. Whereas the noun participatio is used on its own in the Latin version, the Italian translation of TLS exceeds the bounds of equivalence by adding the word “active”: “partecipazione attiva” to it. This happens several times, even though there is no equivalent of “active” in the Latin text.

As accuracy is of primary concern in order to ensure that translations convey the full meaning of the original, it cannot be assumed that the drafter of the Latin version felt no need to include the equivalent of “active” on the grounds that this was implied in “participation.”

As accuracy is of primary concern in order to ensure that translations convey the full meaning of the original, it cannot be assumed that the drafter of the Latin version felt no need to include the equivalent of “active” on the grounds that this was implied in “participation.”

(Incidentally, the Italians were the first to translate pro multis in the Words of Consecration by “for all” on the assumption that “for many” implied “for all,” but this was an erroneous assumption that led to a misunderstanding of the nature of the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass.)

No part of the Latin version of the motu proprio indicates that the Pope envisaged an “active” role for the congregation. Paragraphs 12-14 show that the only authorized lay performers are choir members, women excluded. As the raison d’être of Gregorian Chant was the text, not the people, the intention of the Pope was to clothe the text with beauty (verba liturgiae exornare - to embellish the words of the liturgy), not to make the people vociferate.

Those who insist that TLS was a manifesto for congregational singing make the mistake of giving precedence to so-called “active” participation over the lex orandi (the way prayers and liturgical texts transmit the Faith in the immutable Latin language.)

“A more active part”

The Latin version uses the word vehementius to indicate the manner in which the faithful should participate in the liturgy. This is loosely and incorrectly translated in the Italian and English versions to say that all should play a “more active part” (parte più attiva) in the liturgy, and the impression is given that this is accomplished by everyone singing Gregorian Chant. But the Latin text does not support this conclusion.

Vehementius is related to the Latin adverb vehementer, which has been used throughout classical antiquity, and also in ecclesiastical texts, to indicate intensity of emotions, strength of feelings and other interior dispositions of the human mind. It can be translated by “greatly” or “exceedingly.” (1)

Pope Pius X used it thus: vehementer optemus (we ardently desire) in the Introduction to the motu proprio to show his fervent desire to restore Gregorian Chant. He also used it in his encyclical Vehementer Nos of 1906 to convey the depth of his grief over the injustices to the Church occasioned by the recent French law on State secularism.

Vehementius, the comparative form of vehementer, can be translated by “more ardently / more fervently / to a greater degree.” There are no grounds for believing that the Pope was making a comparison between singers and non-singers or suggesting that the latter were somehow deficient in relation to the former. Rather, he was comparing the suitability of Gregorian Chant and profane styles of music (2) in their ability to enhance prayerful participation in the liturgy.

In § 2, the Pope referred to the special power of suitable sacred music on the minds of the faithful who listen to it (in animis audientium illam), moving them to devotion and making them better disposed for the reception of the fruits of grace coming from the celebration of the Mass. The key concept here is that an intellectual grasp of the nature of the Mass is greatly facilitated by listening to the sublime strains of Gregorian Chant sung by a well trained choir – not by the entire congregation.

In § 2, the Pope referred to the special power of suitable sacred music on the minds of the faithful who listen to it (in animis audientium illam), moving them to devotion and making them better disposed for the reception of the fruits of grace coming from the celebration of the Mass. The key concept here is that an intellectual grasp of the nature of the Mass is greatly facilitated by listening to the sublime strains of Gregorian Chant sung by a well trained choir – not by the entire congregation.

Listening is, therefore, approved by the Pope as a way of participating fruitfully in the liturgy. This is reinforced in § 9, which states that the Chant must be sung by the choir for the benefit of the faithful who listen, and in such a way that it must be intelligible to them, i.e., clearly enunciated so as not to obscure the text. (3)

But, in order to produce the desired effect of appealing to the higher faculties of the soul, especially the intellect, the execution of the Chant must be undertaken by trained choirs: the voices must be pure, restrained, lacking any element of worldliness or self-expression. This was one of the reasons why the Pope did not include a role for the congregation in singing any part of the liturgy.

Sacred music in the Mass has always been regarded as “participatory” for the faithful insofar as it functions to edify, educate and lift them to devotion. So, pursuing one’s private devotions to the background of liturgical chant performed by the choir cannot be interpreted as non-participation. Yet the liturgical reformers argued that a true understanding of the Mass by the faithful required the elimination of such silent prayers in favor of direct vocal participation. Pope Pius X had given no such directive.

“In ancient times”

Liturgists have hastily jumped to the conclusion that the Pope wanted the Church to return to the practice of the early Christians who had included some congregational singing in the liturgy. Where did they get that impression? Certainly not from the Latin version of the motu proprio, which mentions nothing about “ancient times.”

The impression arose from the vernacular texts regarding the meaning of the Latin phrase more maiorum (according to the customs of the ancestors) as used by Pope Pius X in § 3 with reference to Gregorian Chant. The Italian version uses the ambiguous expression “anticamente,” which could mean either in antiquity (4) or simply formerly. The English version, ignoring the second meaning, states that Gregorian Chant used to be the custom in some unspecified “ancient times.” But neither comes near to an accurate translation of more maiorum.

The impression arose from the vernacular texts regarding the meaning of the Latin phrase more maiorum (according to the customs of the ancestors) as used by Pope Pius X in § 3 with reference to Gregorian Chant. The Italian version uses the ambiguous expression “anticamente,” which could mean either in antiquity (4) or simply formerly. The English version, ignoring the second meaning, states that Gregorian Chant used to be the custom in some unspecified “ancient times.” But neither comes near to an accurate translation of more maiorum.

We need to know the relevance of this particular phrase and why it was chosen as being most appropriate. The mos maiorum (custom of the ancestors) was the unwritten code of traditional values observed by the ancient Romans and incorporated into their laws. It represented their time-honored cultural and social practices and provided guidelines for private, political and military life in Roman times. (5)

Just as adherence to tradition gave the Romans a sense of what was fitting and proper, the same could be said for the suitability of Gregorian Chant, which had a long and venerable tradition in the Church. The mos maiorum was the medium of transmission of Gregorian Chant, as the Pope explained: it had been handed down by tradition (quem transmisit traditio).

Now, we can see clearly why Gregorian Chant should be restored to the people: so that, through its special power to move the soul, they can once again participate in the liturgy more maiorum – according to the custom of previous generations of Catholics, before the fashion for theatrical and profane music had invaded the churches.

There is, thus, no reference to or recommendation of congregational singing, which, if it took place at some times and in some places, was never an established and universal custom of the Roman rite. So, it could not have been designated as part of the mos maiorum.

We can be sure that the translation “in ancient times” is false for two reasons. First, because more maiorum refers to an ongoing, unbroken tradition, and, second, because customs that have been discarded for centuries cannot be reincorporated into the liturgy without destroying its intrinsically traditional nature. Indeed, any attempt to do so was later condemned as “antiquarianism” by Pope Pius XII in Mediator Dei.

Continued

Posted March 12, 2014

In the last article we pointed out discrepancies between the Italian and Latin versions of Pope Pius X’s motu proprio, Tra le Sollecitudini (TLS), mentioning that the word “active” had been added to the Italian text to describe the participation of the laity.

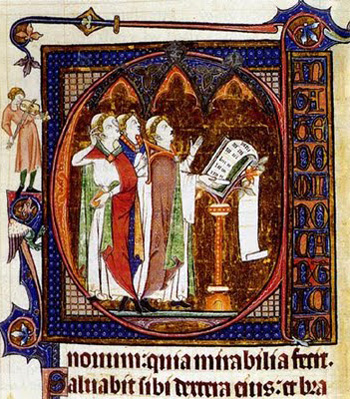

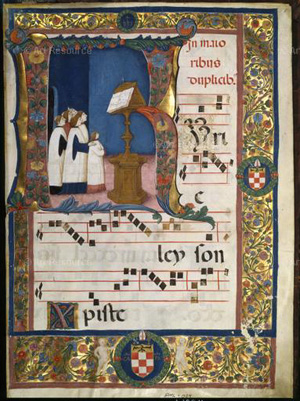

Monks singing chant illustrate a medieval manuscript

Let us examine § 3 of the Latin version, which indicates Pope Pius X’s intentions. It says in a few succinct words that Gregorian Chant, transmitted by tradition, is to be fully restored to the sacred rites: Cantus gregorianus, quem transmisit traditio, in sacris solemnibus omnino est instaurandus.

It then goes on to explain why Gregorian Chant should be given back to the people, so that in particular the Christian faithful may once again, in the custom of their forebears, participate more ardently in the liturgy: Praesertim apud populum cantus gregorianus est instaurandus, quo vehementius Christicolae, more maiorum, sacrae liturgiae sint rursus participes.

Now, we shall examine the pitfalls of having a document in the vernacular (both Italian and English) and the misconceptions that can arise because of faulty translations.

“By the people”

TLS says that Gregorian Chant should be restored nell'uso del popolo (for the use of the people) in the liturgy. It does not specify which people or for what purpose – singing or listening – they are to use the Chant. Even worse, the English version states that the use of Gregorian Chant by the people is what the Pope intended. The underlying suggestion made by these vague and generalized paraphrases is that “the people” means the whole congregation and that the Pope wanted them all to join in the Chant.

But that is an assumption that is not supported by the Latin text, which states that Gregorian Chant is to be restored apud populum, i.e., among or in the presence of the faithful; in other words, in the churches. The Pope had already expressed this idea in his Introduction: ubi Christicolae congregantur (there where the Christian faithful gather).

Apud is a preposition that indicates proximity or geographical location and cannot be translated by a phrase indicating instrumentality, as in something done “by the people.” In saying that Gregorian Chant should be restored to the people, the Pope gave no indication in this passage or elsewhere in the document that he wanted it to be sung by all the faithful.

“Active participation”

The problem revolves around the interpretation of “participation” of the laity in the liturgy as understood by Pope Pius X. Whereas the noun participatio is used on its own in the Latin version, the Italian translation of TLS exceeds the bounds of equivalence by adding the word “active”: “partecipazione attiva” to it. This happens several times, even though there is no equivalent of “active” in the Latin text.

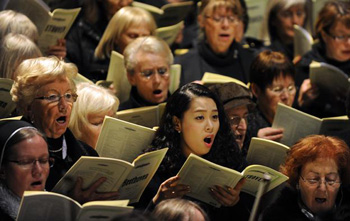

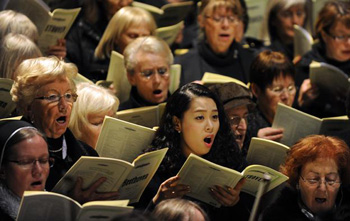

Active participation in singing has become the norm in Catholic churches

(Incidentally, the Italians were the first to translate pro multis in the Words of Consecration by “for all” on the assumption that “for many” implied “for all,” but this was an erroneous assumption that led to a misunderstanding of the nature of the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass.)

No part of the Latin version of the motu proprio indicates that the Pope envisaged an “active” role for the congregation. Paragraphs 12-14 show that the only authorized lay performers are choir members, women excluded. As the raison d’être of Gregorian Chant was the text, not the people, the intention of the Pope was to clothe the text with beauty (verba liturgiae exornare - to embellish the words of the liturgy), not to make the people vociferate.

Those who insist that TLS was a manifesto for congregational singing make the mistake of giving precedence to so-called “active” participation over the lex orandi (the way prayers and liturgical texts transmit the Faith in the immutable Latin language.)

“A more active part”

The Latin version uses the word vehementius to indicate the manner in which the faithful should participate in the liturgy. This is loosely and incorrectly translated in the Italian and English versions to say that all should play a “more active part” (parte più attiva) in the liturgy, and the impression is given that this is accomplished by everyone singing Gregorian Chant. But the Latin text does not support this conclusion.

Vehementius is related to the Latin adverb vehementer, which has been used throughout classical antiquity, and also in ecclesiastical texts, to indicate intensity of emotions, strength of feelings and other interior dispositions of the human mind. It can be translated by “greatly” or “exceedingly.” (1)

Pope Pius X used it thus: vehementer optemus (we ardently desire) in the Introduction to the motu proprio to show his fervent desire to restore Gregorian Chant. He also used it in his encyclical Vehementer Nos of 1906 to convey the depth of his grief over the injustices to the Church occasioned by the recent French law on State secularism.

Vehementius, the comparative form of vehementer, can be translated by “more ardently / more fervently / to a greater degree.” There are no grounds for believing that the Pope was making a comparison between singers and non-singers or suggesting that the latter were somehow deficient in relation to the former. Rather, he was comparing the suitability of Gregorian Chant and profane styles of music (2) in their ability to enhance prayerful participation in the liturgy.

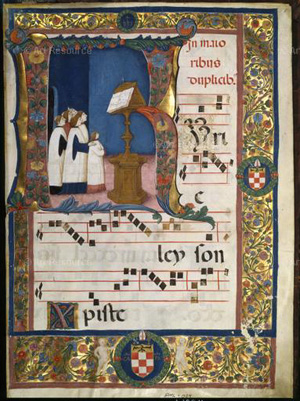

The Pope called for trained choirs of male voices singing pure chant

Listening is, therefore, approved by the Pope as a way of participating fruitfully in the liturgy. This is reinforced in § 9, which states that the Chant must be sung by the choir for the benefit of the faithful who listen, and in such a way that it must be intelligible to them, i.e., clearly enunciated so as not to obscure the text. (3)

But, in order to produce the desired effect of appealing to the higher faculties of the soul, especially the intellect, the execution of the Chant must be undertaken by trained choirs: the voices must be pure, restrained, lacking any element of worldliness or self-expression. This was one of the reasons why the Pope did not include a role for the congregation in singing any part of the liturgy.

Sacred music in the Mass has always been regarded as “participatory” for the faithful insofar as it functions to edify, educate and lift them to devotion. So, pursuing one’s private devotions to the background of liturgical chant performed by the choir cannot be interpreted as non-participation. Yet the liturgical reformers argued that a true understanding of the Mass by the faithful required the elimination of such silent prayers in favor of direct vocal participation. Pope Pius X had given no such directive.

“In ancient times”

Liturgists have hastily jumped to the conclusion that the Pope wanted the Church to return to the practice of the early Christians who had included some congregational singing in the liturgy. Where did they get that impression? Certainly not from the Latin version of the motu proprio, which mentions nothing about “ancient times.”

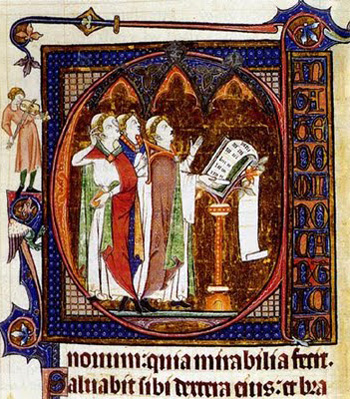

The Pope called for a return to Gregorian chant following Catholic tradition

We need to know the relevance of this particular phrase and why it was chosen as being most appropriate. The mos maiorum (custom of the ancestors) was the unwritten code of traditional values observed by the ancient Romans and incorporated into their laws. It represented their time-honored cultural and social practices and provided guidelines for private, political and military life in Roman times. (5)

Just as adherence to tradition gave the Romans a sense of what was fitting and proper, the same could be said for the suitability of Gregorian Chant, which had a long and venerable tradition in the Church. The mos maiorum was the medium of transmission of Gregorian Chant, as the Pope explained: it had been handed down by tradition (quem transmisit traditio).

Now, we can see clearly why Gregorian Chant should be restored to the people: so that, through its special power to move the soul, they can once again participate in the liturgy more maiorum – according to the custom of previous generations of Catholics, before the fashion for theatrical and profane music had invaded the churches.

There is, thus, no reference to or recommendation of congregational singing, which, if it took place at some times and in some places, was never an established and universal custom of the Roman rite. So, it could not have been designated as part of the mos maiorum.

We can be sure that the translation “in ancient times” is false for two reasons. First, because more maiorum refers to an ongoing, unbroken tradition, and, second, because customs that have been discarded for centuries cannot be reincorporated into the liturgy without destroying its intrinsically traditional nature. Indeed, any attempt to do so was later condemned as “antiquarianism” by Pope Pius XII in Mediator Dei.

Continued

- Thus we read, for instance, in De Bello Africo Commentarius that “Quibus ex rebus Caesar vehementer commotus” (Caesar was greatly alarmed by these things), and in De Bello Civili that his famous Ninth Legion was “vehementer attenuata” (greatly diminished).

- In § 6, the Pope particularly deplored the style of music that had recently been used in the liturgy: “Among the different kinds of modern music, that which appears less suitable for accompanying the functions of public worship is the theatrical style, which was in the greatest vogue, especially in Italy, during the last century. This of its very nature is diametrically opposed to Gregorian Chant and classic polyphony, and therefore to the most important law of all good sacred music. Besides the intrinsic structure, the rhythm and what is known as the conventionalism of this style adapt themselves but badly to the requirements of true liturgical music.”

- Clarity of enunciation was also emphasized by Canon 8 of the Council of Trent.

- This is obviously not the intended meaning here for two reasons. First, Gregorian Chant as a distinctive corpus of music did not exist in the early Christian era. Secondly, the use of the Imperfect Tense “solevasì” in Italian indicates an action that had been going on for an extended period of time (such as the Gregorian Chant tradition), not something that had disappeared a long time ago (such as congregational singing), for which a different Past Tense would have had to be used.

- Virgil’s Aeneid celebrates the mos maiorum of the Roman people, as depicted in the character of Aeneas. He epitomized the Roman ideal of pietas, the core concept of ancient Roman morality which included duties to religion, the family, the wider community and the patria.

Posted March 12, 2014

______________________

______________________

Volume I |

Volume II |

Volume III |

Volume IV |

Volume V |

Volume VI |

Volume VII |

Volume VIII |

Volume IX |

Volume X |

Volume XI |

Special Edition |