|

Organic Society

Two Basic Aspects of the Medieval Mentality

Plinio Corrêa de Oliveira

Medieval society was born from a very intense love for Our Lord Jesus Christ and a profound comprehension of Him. When medieval men spoke of Our Lord, they had a much higher idea of Him than today’s faithful. The admiration of medieval men for His immeasurable perfection intensely and profoundly influenced their attitudes and actions.

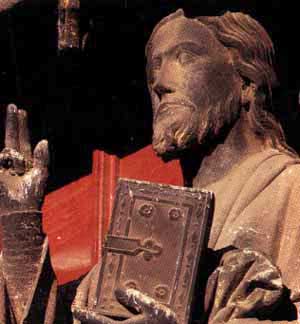

Le Beau Dieu of Amiens reflects the reverence and tenderness the medieval had for Our Lord |

They were particularly touched by His wisdom. They admired how everything He taught was wise, highly elevated, balanced, strong, reaching the final logical consequences. His grandeur was emphasized even more by His miracles, which increased their conviction of His divinity.

This admiration established a great distance between Him and men. Above all, life was not seen as a quest for pleasure. Indeed, because they saw the Redeemer as the One who had offered His life as the extreme sacrifice, who never stepped back in face of any suffering in order to accomplish His mission, they understood that sacrifice was a part of life, breaking the idea that pleasure constitutes the primary pursuit of life.

Here we can measure the difference between this medieval spirit and the modern mentality, whose presupposition is that life is to be enjoyed. In France they used the expression the can-can lifestyle, referring to those immoral dances of the Moulin Rouge cabaret. It defined those who want to enjoy life without any moral barriers. In the United States an analogous approach to life is the Hollywood mentality, which in a certain way was preceded by the Broadway mentality and followed by the Rock ‘n’ Roll mentality. They update the old French model to different and more modern forms of the pursuit for pleasure.

This idea that life is turned to pleasure was not part of the medieval mentality. The principal question to ask about this or that man was whether or not he endured his sufferings as he should. Thus a life was considered splendid and a success if a man accepted and bore his sufferings as Jesus Christ bore His cross to the top of Golgotha. So they asked: “Did he bear his sufferings well?” “Is there evidence that he is heading toward this path?” This was the supreme criterion to judge the behavior of others.

This explains that supreme reverence which we know medieval man had for Our Lord. Such reverence permeated his soul, and reflected in an attitude of respect, confidence, and tranquility of soul in his personal behavior.

From highest to lowest, the medieval assumed

an attitude of a child before God |

At the same time, medieval man had toward Our Lord the great affection of one who felt himself tenderly and personally loved by Him. He knew that he could expect from Our Lord, time and time again, an unlimited patience, forgiveness, compassion, tenderness, and will to help. This caused the medieval man to have in Our Lord the confidence of a small child. We are not speaking of just the little people, but also the most powerful and highly placed, Charlemagne, for example. He had for Our Lord the tender confidence of a small child in the most splendorous of fathers.

One often finds the harmony of these two traits in the medieval iconography, literature and liturgy representing Our Lord: on one hand, a divine elevation with regard to man; on the other, the greatest tenderness for the worst sinner, provided that the sinner be open to the grace of repentance. Thus the man felt himself treated with a great tenderness by Our Lord.

These two simultaneous positions open the soul to be influenced in its depths. One is necessary for the other. Tenderness alone would not move men. Likewise, just an elevated admiration demonstrating His superiority and our inferiority would lead us to rupture with Him. The two – respectful admiration and tenderness – came together and generated what is best in the medieval spirit.

This love produced a virile, balanced and wise man, simultaneously noble and turned toward others with goodness. In my opinion, this is the profile of the medieval man in all those things in which he had transcended the barbarian. Such a mentality gradually gave origin to the medieval institutions marked by this form of wisdom.

The professor was highly respected and esteemed |

This explains why the medieval institutions were very respectable and even august. Let us look, for example, at a medieval university. It was much respected. When a youth would become a full Master, he would be mounted on a horse furnished by the university and conducted through the city streets by clerics wearing the official university garb and insignia to be acclaimed as a new theologian, physician, lawyer, etc. This ceremony, which already treated a new doctor as a great man, demonstrated the desire to impress upon him the idea of the honor, seriousness and dignity of his profession, giving him a keen professional conscience.

Those ceremonies were turned toward honor and respect, unlike the modern graduation ceremonies that are very often turned toward self-interest: a new step toward the goal of making money and enjoying life. Then, the university and society bestowed on a man an honor, for which in return he was expected to exercise his new profession with a great respectability and seriousness.

The way the medieval student treated a great professor was also expressive. The Middle Ages was the epoch of great professors. When a professor would give a magnificent class, it was not rare for his students to take off their capes and place them on the floor as a carpet for the master to step on as he left the building. When a class was extraordinarily outstanding, the students would follow the professor on his way home acclaiming him before the population and repeating the same ritual of the capes until he had crossed the threshold of his home. In this way, they showed the whole city how honorable and respectable the professor was.

Today, to appear as important, a man buys an expensive automobile. Without a costly, shiny new car there is no respectability. It was not always like this. Then, there were no cars, and a man did not need a carriage or excellent horse to be important. His university title was a formidable thing in itself, because it represented a great wisdom, sacrifice and talent.

This demonstration of respect for a young professional or a great professor also applied to the other fields of human activity. It achieved its highest expressions in an admiration for those who dedicated their lives to defend the Catholic Faith and the lives of the people, that is, the knight, and those who offered their whole lives to the Church, the clergy.

In this general tribute of respect, we find in the medieval mentality the two simultaneous types of admiration – veneration and tenderness.

Posted November 26, 2007

| | Prof. Plinio |

Organic Society was a theme dear to the late Prof. Plinio Corrêa de Oliveira. He addressed this topic on countless occasions during his life - at times in lectures for the formation of his disciples, at times in meetings with friends who gathered to study the social aspects and history of Christendom, at times just in passing.

Atila S. Guimarães selected excerpts of these lectures and conversations from the trancripts of tapes and his own personal notes. He translated and adapted them into articles for the TIA website. In these texts fidelity to the original ideas and words is kept as much as possible.

Related Topics of Interest

Nobility and Accessibility: Keys of Catholic Culture Nobility and Accessibility: Keys of Catholic Culture

The Role of Admiration and Affection in the Family The Role of Admiration and Affection in the Family

Vocations of the European Peoples Vocations of the European Peoples

Lutheran and Calvinist Mentalities Lutheran and Calvinist Mentalities

The Organic Formation of Feudalism The Organic Formation of Feudalism

What is Organic Society? What is Organic Society?

The Decline of Feudalism and Growth of the Modern State The Decline of Feudalism and Growth of the Modern State

False Statements About the Middle Ages False Statements About the Middle Ages

Revolution and Counter-Revolution in the Tendencies, Ideas, and Facts Revolution and Counter-Revolution in the Tendencies, Ideas, and Facts

|

Organic Society | Social-Political | Home | Books | CDs | Search | Contact Us

© 2002-

Tradition in Action, Inc. All Rights Reserved

|

|

|