|

Organic Society

The Organic Formation of Feudalism

Plinio Corrêa de Oliveira

By the end of the Western Roman Empire, there were colossal estates of land, which gave rise to difficult and complicated agrarian questions. Despite this, when one considers the Western Roman Empire at the time of Constantine’s conversion, there were many Romans with large estates who had converted to Catholicism and had given the Church enormous properties. It is true that between the conversion of Constantine (312) and the conversion of Clovis (496) almost two centuries had passed, but with regard to property, the situation was much the same. Already at the end of the Roman Empire, because of the Christian influence, slaves were being freed and a system of small property owners was emerging that had similarities with the Feudalism that would come.

On the other hand, once the great barbarian invasions ceased, there was a period of time when the different races integrated and started to establish the various regions of Europe. For example, in France there were fundamental differences among the Bretons, the Gascons and the Alsatians, but at a certain moment they had integrated sufficiently to make up what is called the French people. The same happened with other peoples, who after a period of integration, came to constitute a whole. This was the moment when the Middle Ages started. It is a simplified way to present History, but it is essentially what happened.

Medieval society sprouts

With Charlemagne one is in the Middle Ages. It is a time when the period of barbarians and the period of the Moors merged. I would say that even before the Carolingians, under the Merovigians, the Middle Ages was already present.

Pope Leo III crowns Charlemagne as Emperor |

Charlemagne’s Empire was a magnificent institution established and supported by the Holy See. His grandfather, Charles Martel, had expelled the Moors from France and broken their impetus at the Battle of Poitiers (732). The Moors remained on the Iberian Peninsula – Spain and Portugal – and were expelled only when Boabdil, the last King of Granada, was sent out of Spain by King Ferdinand of Aragon and Queen Isabel of Castile in 1492. But the Arabs from the Iberian Peninsula were no longer able to cross into France and go wherever they wanted in Europe. Their momentum had been broken at Poitiers.

Charlemagne fought not only the Moors, but also the barbarians who came from the North and the East. He faced waves of German barbarian tribes invading the territories along the borders of the Rhine and Danube Rivers that would later constitute Germany and Austria. Facing those surges of barbarian hordes was an endless effort. After one tribe was defeated, another would come, and no one could predict when such attacks would end.

Charlemagne combated as a perfect Catholic warrior, facing the enemy stalwartly without knowing if he would ever see a final victory.

When the German danger was almost under control, another invasion began: the sailor-kings - the Vikings - the Norsemen who entered his Empire by way of the French rivers. They were very agile sailors who invaded France from the north in their relatively small boats, attacking, burning and looting innumerable cities. Charlemagne died at the point when this invasion was starting.

After his death the Empire had a short period of union under the government of his son Louis the Pious, but soon it entered into civil wars caused by multiple disputes among his grandsons. His sons and grandsons were so insignificant that when the Chanson de Geste sang the glory of Charlemagne, it honored his nephew – Roland – as his perfect follower and not one of his direct progeny. No one took them into much account.

The grandsons of Charlemagne, Lothar, Pepin, Louis and Charles, were also unable to hold for long either front of the war, in the Pyrenees against the Moors, or on the Rhine-Danube against the Germans. Those Kings utterly failed to organize an efficient system of defense such as their grandfather had achieved.

The local lord organized the defense of his people

In this situation, the great landowners felt the need to defend themselves against both dangers – the Arabs and the Germans – that were knocking at their doors. The immediate problem for these property owners was no longer to defend the whole Empire, something they knew they could not do, but rather to defend their own area, the local church that housed the Blessed Sacrament and relics of saints, their families and the families of their workers, as well as their sources of income, i.e., the land, crops and livestock.

Catholics suffered constant military harrassment from the Arab and German invaders |

Naturally, in order to defend themselves against those common enemies, the landowner and the peasants who worked the land joined together. Both owners and workers fought together in an alliance to avoid losing their respective properties. Yes, the workers also had properties, small pieces of land with some livestock and crops. Perhaps the peasants had even more reason to fight than the large landowner, because for them, their land represented their whole property, while the master might still have other lands elsewhere. So, facing a common enemy the collaboration of two social classes – the owners and the laborers – became very close and strong.

Before this general breakdown of order, a landowner would appeal to the central power when his property was invaded, as we would today. However, this no longer worked because the old Roman roads had fallen into ruin. A long time could pass before the central government received the message that an area was being invaded; then more time would elapse before the King’s troops would arrive to defend the area. By that time, the enemy was already far away, burning and looting other places. Therefore, a local defense had to be prepared and maintained.

In practice, the King ceased to have any function. He was still the King who wore a crown and received special honors and protocol. But on the practical level of defense, no one could expect his protection in face of immediate danger.

Catholic warriors of the 9th century |

Everyone still had a monarchical mentality, but in the order of facts, the monarchy was like a mist in the air, without any concrete means to govern the kingdom. The local authority needed to take over the defense or everything would be lost.

The simple laborers, who understood that they needed someone to command them, adopted a principle that is fundamental to organic society. Before that time, when there was peace in the land, several officials appointed by the Emperor would exercise the various offices for the area. One governed, another was the judge, another was in charge of the police, etc. If one of those officials died or moved, another would temporarily accumulate two or more functions. Only the priest’s functions could not be assumed by a lay person. So, in face of a weak central power and realizing that a strong defense relied on a single leader, the people tended to place all the various functions into the hands of the landowner. He became simultaneously the governor, judge, chief of police, etc. Theoretically he still relied on the King, but in practice he was the one who commanded.

Everywhere these small kings, who still paid respect to a central but inefficient King, started to sprout up. For the peasant, the King was a mythical personage; but the one who resolved his dispute with the man who stole his cow was the landowner of his territory. He was the one whom he dealt with, who actually mattered. This owner was called the feudal lord.

This process explains the birth of Feudalism. It describes the essence of Feudalism. It is the regime which, by force of circumstance, added the right to rule to the right of ownership. Feudalism was the addition of local power to the right of property.

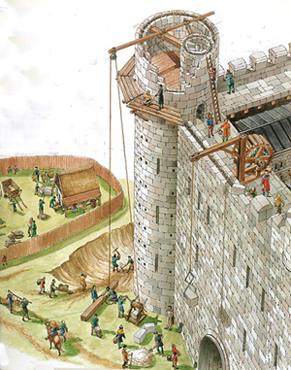

Both the lord and the local population built the castle

Given this situation, it was natural that the local population would voluntarily help the feudal lord to build a common fortress to protect them all should the enemy draw near. In face of that constant threat, the protection of such a fortress was essential. This fortress was the castle.

The noblest and more secure part of the castle housed the chapel where the Blessed Sacrament and the sacred relics were kept. They deserved to be saved above everything else. Thus, the chapel was in the center of the fortress. When the inhabitants of the area heard that the enemy was approaching, they would flee to the castle. A long procession of families carrying what possessions they could save would enter the castle gates. Inside, they would encounter God, present in the Blessed Sacrament. There they had full access to the Sacraments of the Church; the vicar heard their confessions, celebrated Mass for them, gave them religious instruction, preached the fight as a sacred duty, spoke to them of Heaven and explained that they could attain eternal salvation if they fought defending the Catholic Religion, which also was assailed when the Moors or barbarians attacked the fief.

Nobles and peasants joined together to build the common defense, the castle |

Inside the castle lived the feudal lord, also in the center of the castle, often in the tower. One of his duties was to be the first in attack and the last in retreat. He led the fight and was the very soul of the defense. If his castle was a small one, he counted on perhaps five to ten knights for the defense, as well as some infantry, 15 archers and 20 or 30 lances, as the foot soldiers carrying these weapons were called. With these simple armed bodies that lacked any sophisticated training, the lord would set out from the castle gates on expeditions or skirmishes. If the enemy was surrounding the castle, the lord organized its defense from the high walls and exterior towers, where the soldiers would shoot arrows, throw stones or pour boiling oil on the enemy.

In the background, the women would assist the men in the defense as much as they could. Should the enemy conquer, the lord would remain fighting in his tower to his last breath. Or, should all be lost, he might go with those who still remained to a basement tunnel, which would lead him to a hidden place from which he could reach the castle of some nearby relative.

Often, the wall and towers of the castle were strong enough to discourage a long siege. The enemies, after looting the houses abandoned by the peasants, killing some livestock, and destroying the crops, would go on their way to the next village or an easier target. The lord and his men would attack the rear guards of the enemy, inflicting what harm they could to avenge the damages, punish the guilty and raise the morale of the people.

The castle, therefore, was a place of defense where all the peasants found refuge in hours of danger and distress.

After the Saracen and barbarian dangers had passed, this dust made up of very small “kingdoms” – which were called fiefs – entered into a general process of assimilation. This happened organically, without the need for a planning commission of the U.N. or Maastricht. They merged together and formed larger fiefs with larger cities, all offering homage to the King. So, from the grassroots up, the old kingdoms were reconstituted, with the exception of Lotharingia. History saw France, Germany with its Roman German Empire, and several kingdoms in Spain restarted in this way.

From that dust made of small unities, Feudalism advanced to form civil organizations with their respective organized States. This is how the Western World from which we came was founded.

Posted July 12, 2007

| | Prof. Plinio |

Organic Society was a theme dear to the late Prof. Plinio Corrêa de Oliveira. He addressed this topic on countless occasions during his life - at times in lectures for the formation of his disciples, at times in meetings with friends who gathered to study the social aspects and history of Christendom, at times just in passing.

Atila S. Guimarães selected excerpts of these lectures and conversations from the trancripts of tapes and his own personal notes. He translated and adapted them into articles for the TIA website. In these texts fidelity to the original ideas and words is kept as much as possible.

Related Topics of Interest

Vocations of the European Peoples Vocations of the European Peoples

The Personality of Charlemagne The Personality of Charlemagne

Overview: Revolution and Counter-Revolution Overview: Revolution and Counter-Revolution

What is Organic Society? What is Organic Society?

The Steps of an Organic Relationship The Steps of an Organic Relationship

Organic Society and Desire of Heaven Organic Society and Desire of Heaven

The Moon and its Halo The Moon and its Halo

Departure for the Crusade: A Desire for Sublimity Departure for the Crusade: A Desire for Sublimity

Groups of Friends and Guilds Groups of Friends and Guilds

|

Organic Society | Social-Political | Home | Books | CDs | Search | Contact Us

© 2002- Tradition in Action, Inc. All Rights Reserved

|

|

|