|

World History

Refuting the Anti-Catholic Lies

of the e-pamphlet Life in the 1500’s

Marian T. Horvat, Ph.D.

Notre Dame, Paris

Cathedral of Cologne, Germany

Cathedral of Milan, Italy

Cathedral of Segovia, Spain

Mont St. Michel, France

|

The other day I received an e-mail titled “Life in the 1500s’ – a preposterous list of tales that all insinuate how hard, dirty and backward life was in the supposed “Dark Ages” of Christendom. (Actually, historians consider the 1500s the Renaissance/Early Modern period, so even the date is misleading.) These stories are so inaccurate it is difficult to believe that anyone with a higher than elementary education could take them seriously.

But several friends assured me that this e-mail has been going around for a long time, and that some uninformed people today believe these tales, since they are broadly spread by movies and television shows presenting the people of the Middle Ages as dingy, drab, and wallowing in miserable hovels while all the nobles lived in castles. Sometimes the falsification is deliberate, sometimes unconscious; but always the past is altered to suit the prejudice of the present against the time of Christendom.

The language of the facts

Now, let me present some historical facts in order to vaccinate my reader against what has been affirmed in the unfortunate e-mail on the Internet.

It is an insidious contrivance, in my view, to present the marvelous Age of Faith as a backward era filled with a superstitious, barbarian people who were more unintelligent and irrational than modern people. I think it is time to lay such myths to rest.

It is enough to view the grand cathedrals that were erected in the Middle Ages to realize that the people who built and enriched them with glorious works of art were far from backward. Consider, for example, this small sampling at left from various countries of Europe (at left, top to bottom):

• Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris, constructed in the 13th century;

• the Cathedral of Cologne, on the Rhine, begun in 1248, next to the Town Hall in the old section of the city;

• the magnificent Cathedral of Milan in Lombardy, Italy begun in the 14th century and still today, the third largest in the world;

• the Cathedral of Segovia, built in the 1500s;

• the island monastery Mont St. Michel in France dating from the 8th Century and today a premier tourist site;

• (Below, left to right) St. Stephen’s Cathedral, a Gothic masterpiece in Vienna, built largely in the 14th and 15th centuries;

• Salisbury Cathedral, the English version of the Gothic completed in the 13th century,

• St. Mark's Cathedral in Venice, begun c. 1050 and completed in the 1090s. As the private chapel of the Doges, it became a focus for state ceremonies as well as a place of pilgrimage.

This is not to mention the Cathedrals of Laon, Strasbourg, Worms, Siena, Pisa, the Duomo, or the sprawling Santiago de Compestella, the 13th century pilgrimage site crowning a city that looks today much as it did in the 1500s.

The list goes on and on. Every year Americans travel to Europe to view and marvel over these architectural masterpieces that reflect the spirit and mentality of the Catholic peoples who built Christendom.

In the next section, the paragraphs from “Life in the 1500s” will be in blue italics; my response will follow each historical invention.

Left to right, Cathedral of Vienna, Austria; Cathedral of Salisbury, England; St. Mark's Cathedral, Venice

Bathing & bouquets

The next time you are washing your hands and complain because the water temperature isn't just how you like it, think about how things used to be. Here are some facts about the 1500's:

Most people got married in June, because they took their yearly bath in May and still smelled pretty good by June. However, they were starting to smell, so brides carried a bouquet of flowers to hide the body odor. Hence the custom today of carrying a bouquet when getting married.

15th century illustration of a midwife attending a birth. The baby is washed in a fresh water basin immediately after birth. |

These are not facts, but falsehoods.

Many people married in May or June because they were Catholics and the Church wisely proscribed marriages from being celebrated during the Lenten season, a time of abstinence and penance. By the way, this pious law continued to be followed by good Catholics until Vatican II swept out so many of the good traditions that developed in the Age of Faith.

As for the yearly-bath myth, medievalists have long laid to rest the idea that people rarely bathed in the Middle Ages. The Middle Ages was a period of hygiene and cleanliness. The first bit of evidence we have is the prevalence of soap, a common product used for washing clothes and washing people. Next, there are multiple references in literature and manuscripts to bathing, treated matter-of-factly, as something common place. Charlemagne, for example, used to bathe each morning in a large pool or river, where he would meet with his ministers, who were also invited to bathe.

Bathing was part of a ritual before certain ceremonies, such as knighthood, and in the romances of chivalry we see that the laws of hospitality required offering guests a bath before they dined.

Scenes from 14th century thermal baths houses, popular at the time. The establishments were served by river currents

|

The first etiquette manuals (13th century), as well as the various monastic Rules, specified washing the hands before eating, and keeping the hair, fingernails and clothing clean. Clearly, washing was frequent – there is evidence all over the place for people washing their hands, faces and feet on a daily basis.

Monastic rules usually had previsions that stipulated washing one’s hair and bathing once each week, usually on a certain day. We can also see how the medievals utilized running rivers or streams. The monks of Cluny were the first to take advantage of the nearby running stream to use as a type of indoor plumbing system. One can still find there numerous lavatories close to the refectories.

A saying in France from those days shows how cleanliness was considered one of the pleasures of existence:

Venari, ludere, lavari, bibere; Hoc est vivere!

(To hunt, to play, to wash, to drink, - This is to live!)

One thing I might add, care should be taken not to attribute to the 13th century the revolting uncleanliness of the 16th and subsequent centuries which, in France at least, has continued up to our own time.

As for the bridal bouquet, it was one of numerous beautiful symbolic customs that developed around the Sacrament of Matrimony that we have inherited. For the medieval mind, which saw in all nature a reflection of the Creator, each flower had a symbolic value and displayed a message.

Orange blossom, popular for bridal bouquets, denoted chastity, purity and loveliness. A sprig of ivy was included in bouquets as a symbol of fidelity. Roses represented love, and the lily of the valley, happiness, and so on. The flowers of the bridal bouquet had real meaning; they were not meant to disguise foul odors from a supposedly unwashed bride and groom.

Baths & babies

Baths consisted of a big tub filled with hot water. The man of the house had the privilege of the nice clean water, then all the other sons and men, then the women and finally the children! Last of all the babies. By then the water was so dirty you could actually lose someone in it. Hence the saying, "Don't throw the baby out with the bath water.”

I guess if you believe that there was only one bath a year for most persons in the 1500s, then you can believe the family bath water would be so filthy you couldn’t find the baby...

First, the bathing tubs for babies in the 1500s, like today, were small basins, different from the tubs used for adults.

Second, the saying first appeared in English only in the 19th century in the writings of Thomas Carlyle (1853), who reported, 'The Germans say, 'You must empty out the bathing-tub, but not the baby along with it.' The saying, which in itself is proof that babies were bathed often, actually was used in a different context: ‘Don’t be careless. Don’t confuse the essential with the dispensable.”

Thatch roofs & canopy beds

Houses had thatched roofs-thick straw-piled high, with no wood underneath. It was the only place for animals to get warm, so all the cats and other small animals (mice, bugs) lived in the roof. When it rained it became slippery and sometimes the animals would slip and fall off the roof. Hence the saying "It's raining cats and dogs."

There was nothing to stop things from falling into the house. This posed a real problem in the bedroom where bugs and other droppings could mess up your nice clean bed. Hence, a bed with big posts and a sheet hung over the top afforded some protection. That's how canopy beds came into existence.

|

Traditional thatched cottages in Ireland (above), England and Brittany (below)

|

Tradition 16th-century Brittany cottage (above); English thatched houses, below

|

This explanation about “raining cats and dogs,” an expression that first appeared in the 17th century, is a complete hoax. The fact is that many peasant cottages and town buildings in England, Ireland, Wales, and parts of France and Belgium had thatched roofs.

Far from being piles of straw piled high, a thatch roof was a tightly woven mat made with wheat reed, long straw, or Norfolk reed. Such a roof had the advantage of keeping a cottage cool in the summer and warm in the winter with no need for artificial insulation.

Let the reader view some of these supposedly primitive thatch roofs and he will see that not only are they charming, but it would be impossible to house sleeping dogs and cats in them. At right, you can see some typical thatched hut cottages built in the styles of various regions.

Thatch roofs were not just for peasant houses; many town dwellings and country houses used them as well, especially in Brittany, France, where such homes are highly valued and preserved today. In fact, the thatch roof has seen a revival in popularity today on the Continent, and master thatchers are in high demand. The cost of their construction today is quite high, however, which only allows the well-to-do to have what was a common place luxury for the man of the 1500s…

Canopy bed of King Philip II (1527-1598) at the Escorial, built in the 1500s

|

As for the canopy bed, we are facing another complete fabrication. The canopy bed originated in the homes of the royalty and nobles for both symbolic and practical purposes.

In the 13th century, when bed canopies first appeared, sleeping places in castles often doubled as spaces for receiving guests, so the bed with a canopy signified the status of the lord and lady. The tall wood posts were adorned with rich tapestries and materials that also served to ward off the cold and assure privacy from servants and attendants, who might be sleeping at night in the same area.

By the 1500s, the canopy bed had also become popular in the homes of the prosperous bourgeoisie, who emulated the nobility in their fine clothing, tasteful furniture and good manners. This is why all the social levels in the Middle Ages tended to rise culturally and materially, the opposite of today, when all levels of the social sphere are increasingly adopting vulgar and egalitarian styles and customs.

Dirt floors & threshholds

The floor was dirt. Only the wealthy had something other than dirt. Hence the saying "dirt poor." The wealthy had slate floors that would get slippery in the winter when wet, so they spread thresh (straw) on the floors to help keep their footing. As the winter wore on, they added more thresh until when you opened the door it would all start slipping outside. A piece of wood was placed in the entranceway.

Hence the saying a "thresh hold."

The word origins of both terms above are again completely false and had nothing to do with the 1500s. The term “dirt poor” was first used in the 1930’s, and used in reference to the Protestant hillbillies of the Ozarks and Oklahoma who lived in extreme poverty and unclean conditions. The medieval Catholic peasants who may have been poor were generally “clean poor.”

The term threshold came from the middle English verb threshhen, which meant to stamp on or trample (e.g. threshing wheat). It is uncertain how the term threshold originated; perhaps because the entrance place was where one stamped his feet to clean them of mud and debris, another indication of the good habits of our civilized medievals.

In the early medieval period, skins of animals were used on the floor, and later rugs, to protect the feet from the cold stone floor. In the poor homes, straw mixed with fragrant herbs was strewn on the polished dirt or stone in the winter, also for purposes of warmth.

The picture of nobles slipping and sliding on their slate floors is as fabricated as the notion that they were throwing straw on the stone, marble, slate, plaster, or wood floors of their palaces and town houses. Such floorings were made to last through centuries – unlike the plastic linoleum of the modern house, and are highly prized today not only for their historical value but for their beauty and durability.

I present you with some pictures of the grandiose palaces and country manors that the wealthy would have inhabited in this period. Can you even imagine throwing straw on the floors of such edifices? Myths like these which try to propagate the idea of an uncouth, loutish populace are not just misleading, but malicious, in my view.

The Alcazar of Segovia, Spain

Burg Eltz, Germany

Edinburgh Castle, Scotland |

Chambord, southern France

Valencey, southern France

Penhurst Place, Kent, England |

Left, top: The imposing Alcazar of Segovia in central Spain was built in the 12th century by King Alfonso VI of Castile. It is hardly a rustic structure.

Left, center: Built in the 12th century, Burg Eltz sits above the town of Moselkern in Germany. It has been called the only perfectly preserved German castle. Burg Eltz is what is known as a Ganerbenburg, a castle with several owners, each of whom had his residence within the castle.

Left, bottom: Edinburgh Castle has dominated the capital city's skyline just as it has dominated Scotland's history for 900 years.

Right, top, middle: the Chateaus of Chambord and Valencay constructed in the 1500s make up part of a whole chain of magnificent country chateaus in southern France. Called the “Marvels of the Val de Loire,” they attract a multitude of tourists each year.

Right, bottom:The medieval masterpiece Penhurst Place, in Kent, completed in the 1500s, today the home of Viscount de L’Isle.

Then, lest you imagine the townspeople and peasants living in primitive conditions, let me show you samples of some rustic and town dwellings that have survived to our times. Many American tourists like to seek out the old medieval towns and country places throughout Europe to marvel at the homes of character, comfort and beauty that vary from region to region.

San Gimignamo, Italy

A Tuscan village

Florence, Italy

Marketplace of Tubingen, Germany |

Village houses in Kellerei, Germany

Venice, Italy

Hospices of Beaune, Burgundy, France |

As you can see by this small sampling of pictures, there were not just two classes, a very wealthy and a very poor, an idea that is often generated by hoaxes like this and other anti-Catholic literature. By the 1500s, in fact, there was a large and prosperous middle class, the bourgeoisie, which itself was divided into an upper, middle and petite bourgeoisie. The farmers and peasants were likewise spread into various levels, with all the groups intersecting harmoniously.

Left, top: The medieval “city of towers” of San Gimignamo in Tuscany looks today much as it would have in the 1500s, a testimony to the amiability of past village life. It still is famous for the cultivation of saffron, an extremely popular medieval spice. Would it be so bad to live in such a city? I think not.

Below, Radi, close to Siena, another charming Tuscan medieval village.

Left, third: The centuries old houses of Florence that set over the Arno River, a scene unchanged for centuries.

Left, bottom: The marketplace in front of the town hall of Tübingen gives an idea of the vivacity and color of the lower classes in the Middle Ages.

Right, top: The town of Kellerei in the wine-growing region of Germany

Right, middle: the colorful houses of Venice stand as testimony to the medieval imagination.

Right, bottom: Hotel-Dieu is the treasure of Beaune (France) - a ‘medieval jewel’ with its distinctive multi-colored Burgundian roof tiles. It was originally a hospice founded in 1443 as a charity house for the poor and infirm - hence the name, "God's Hotel." Today it houses the Museum of Wine of Burgundy.

Porridge & feasts

In those old days, they cooked in the kitchen with a big kettle that always hung over the fire. Every day they lit the fire and added things to the pot. They ate mostly vegetables and did not get much meat. They would eat the stew for dinner, leaving leftovers in the pot to get cold overnight and then start over the next day. Sometimes stew had food in it that had been there for quite a while. Hence the rhyme, "Peas porridge hot, peas porridge cold, peas porridge in the pot nine days old."

Sometimes they could obtain pork, which made them feel quite special. When visitors came over, they would hang up their bacon to show off. It was a sign of wealth that a man could "bring home the bacon." They would cut off a little to share with guests and would all sit around and "chew the fat." Getting quite an education, aren't you?)

Quite a bad education with such an imaginary etymology of sayings, I would say.

A medieval feast pictured from the Book of Hours of the Duke of Berry (early 1400s)

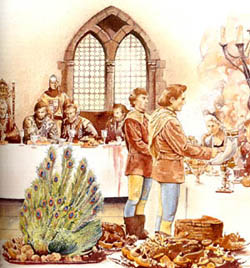

Another portrayal of the munificence of a late medieval feast

A typical tavern scene from the 15th century in one of the burgeoning Flemish urban centers |

The origins of these popular sayings, once again, are wrong. How the “peas porridge pot” rhyme came into being is unknown. The terms “chewing the fat” and “bringing home the bacon” seem to be American terms from the 19th century. Nothing medieval or even Renaissance about them.

What I protest is the general view being presented that “the people” – I guess that would include all the people, and especially the poor - had a very restricted bill of fare and primitive palate. The starving people would have subsisted on a single pot of porridge for nine days.

The charge is absurd in itself, since if the people were starving, they would have eaten the whole pot of porridge the first day. Also, the medievals were quite conscious of the dangers of food poisoning. They would have never taken chances with the rancid food of a nine-day-old pot of porridge.

So what did they eat? Today, there are numerous documents, including cookbooks from the 15th century, that show the palate of the nobles and bourgeoisie was very refined and their tables laden with a variety and quality of meats and foods that we find staggering today. We also learn that food was very well, even exquisitely cooked.

A late medieval banquet given by Count Gaston IV at Tours in 1457, for example, had seven courses, opening with spiced wine and dipping toast, moving on to grand pâtés of capon and ham and seven different kinds of pottage, all served on silver. Ragouts of game came next: pheasants, partridges, rabbits, peacocks, geese, swans and various river birds, not to mention venison. After this, a dish called oiseaux armes, where all the food was apparently gilded, or at least gave the appearance of being golden. The fifth course was tarts and fried oranges, the sixth, a red sweet wine served with wafers, and finally fruits and nuts (Feast, a History of Grand Eating, by Roy Strong, Harcourt, Inc.: 2002).

A meal at a country manor or merchant’s house would regularly serve four platters featuring, for example, capon with herbs, gross meats, jelly and a cream tart to revive the taste buds for the next platter, which could be stuffed shoulder of mutton and perch in yellow sauce. The meal would end with cooked pears, and shelled nuts and spiced wine (from the 14th century Le Menagier de Paris).

Peasant fare would be what we consider very healthful eating today. Brew (beer and ale) in England and wine on the Continent were mainstays at the peasant table. Bread and porridge were the principle staples, along with the companaticum (food accompanying bread, such as sausages, cold cuts, or cheese). Then there was the legumes (beans, peas and lentils), and garden vegetables (radishes, celery, squash, carrots, cabbage, onions, cucumbers in the East, and later also lettuce and spinach,) a multitude of herbs, and the various fruits and nuts of the areas.

Meat would have been more or less plentiful, taking into consideration the large differences in means in this class. Even more common than sheep and pigs were poultry, chickens, ducks, pigeons and geese. Some peasants also kept bees.

Tomatoes & bread

Those with money had plates made of pewter. Food with high acid content caused some of the lead to leach onto the food, causing lead poisoning death. This happened most often with tomatoes, so for the next 400 years or so, tomatoes were considered poisonous.

Scenes from the Hours of the Duke of Berry (early 1400s) refute the lies about the miserable lives of peasants

Above, a herd of sheep in the barn, and a warm fire indoors provide security and comfort

The July harvest and shearing season

A peasant hits the trees for acorns

to fall for his pigs |

A blatant falsehood, easily refutable. The tomato, native to the Americas, was only introduced in Europe in the 16th century, and was quickly accepted in the kitchens of Spain and southern Europe. In Britain and the North, it met with more resistance because the tomato plant was associated with the plant family that included the poisonous mandrake and deadly nightshade.

There are no instances I know of in medieval medical records – which were quite extensive by the 1500s – of any kind of poisoning being associated with pewter. That is because the tiny amount of lead leached from a pewter plate or vessel during a meal would be wholly inconsequential.

In fact, the most widespread use of pewter was in the 17th century, when pewter was the metal of choice for many household goods in England and colonial America. It was only in the 1970s that lead poisoning become a matter of health concern and topic of study, and pewter manufacturers began to make “lead-free” pewter. Incidentally, it is now known that one of the highest sources of lead came not from pewter, but from soda pop cans made in the 1960's.

Bread was divided according to status. Workers got the burnt bottom of the loaf, the family got the middle, and guests got the top, or "upper crust."

Again, this has nothing to do with the Middle Ages. A loaf of bread was served then, as now, whole. No one would have thought of cutting off the top and serving that “layer” to the master. If a loaf burned, no doubt what was good was salvaged in some way, as it would be in any times.

The expression “upper crust” developed much later in the 19th century, and actually refers not to bread, but to a pie symbolizing the population, with the upper class being at the top.

Wakes & death

Lead cups were used to drink ale or whisky. The combination would sometimes knock the imbibers out for a couple of days. Someone walking along the road would take them for dead and prepare them for burial. They were laid out on the kitchen table for a couple of days and the family would gather around and eat and drink and wait and see if they would wake up. Hence the custom of holding a "wake."

England is old and small and the local folks started running out of places to bury people. So they would dig up coffins and would take the bones to a "bone-house" and reuse the grave. When reopening these coffins, 1 out of 25 coffins were found to have scratch marks on the inside and they realized they had been burying people alive. So they would tie a string on the wrist of the corpse, lead it through the coffin and up through the ground and tie it to a bell. Someone would have to sit out in the graveyard all night (the "graveyard shift") to listen for the bell; thus, someone could be "saved by the bell" or was considered a "dead ringer."

And that's the truth... Now, whoever said that History was boring ! ! !

Educate someone... Share these facts with a friend.

Death was a very serious subject in the Age of Faith. The Church taught that all of life should be directed to the four last things, death, judgment, heaven or hell. For that reason, the rituals of death and burial were extremely important in the life of noble or peasant. A priest was always called if death were imminent to give the Last Rites and Blessed Sacrament. The wake provided the opportunity for family members and friends to gather together and offer prayers for the deceased soul to shorten his time in Purgatory.

The Church always condemned those occasions when wakes turned into occasions of drinking and merriment. For example, Robert Grosseteste, Bishop of Lincoln (12th century), warned that a dead man’s house should be one of “sorrow and remembrance,” not one of “laughter and play.”

Since these hoaxes deal specifically with England, I might note that the Protestant doctrine of the afterlife, which rejected Purgatory, brought greater prominence to secular aspects of the burial ritual. It was not long before Protestant doctrine was taken to its logical conclusion and burial became a secular ceremony conducted by the laity.

As for the sitting up all night to permit the corpse to awaken and ring a bell, the whole notion is ludicrous. The medieval man was not so stupid that he could not tell when a man had died. In monasteries and convents a wake was often extended for three days and nights, or until the body showed signs of putrefaction, a sure sign of death.

A simple review of the history of English burial practices shows that coffins were rarely used in the 1500s, making “the 1 in 25 coffins with scratch marks” a historical impossibility. The great and the wealthy were buried inside the churches. The norm, however, was a shroud burial straight in the ground in an unmarked grave, and often bodies were buried on top of others already interred.

It was later, in 17th and 18th century Protestant England, when the bones of those long dead might be removed to a charnel house, or ossuary, or to a crypt under the church, and the resurrectionists or body-snatchers began to steal bodies to supply the medical profession with corpses for scientific study.

Conclusion

I hope these explanations will help Catholics to question the many myths that circulate about the Middle Ages that have the ultimate aim of denigrating Christian Civilization.

I suggest that you take this opportunity to educate someone – share these facts with a friend.

Posted August 18, 2005

Related Topics of Interest

Defending the Crusades Defending the Crusades

The Swan's Song of Galileo's Myth The Swan's Song of Galileo's Myth

Gargoyles: Symbol of the Existence of Original Sin Gargoyles: Symbol of the Existence of Original Sin

Vice and Virtue Symbolized in the Animal Kingdom Vice and Virtue Symbolized in the Animal Kingdom

Symbol of the Crown in the Reign of Mary Symbol of the Crown in the Reign of Mary

Nourishing an Appetite for the Marvelous Nourishing an Appetite for the Marvelous

Related Works of Interest

|

History | Home | Books | CDs | Search | Contact Us | Donate

© 2002- Tradition in Action, Inc. All Rights Reserved

|

|

|

|