|

Organic Society

Patriarchs in the Middle Ages

and in Ancient Rome

Plinio Corrêa de Oliveira

In the Middle Ages, many landlords living in a particular area were related among themselves. They descended from the same chief, the same founder, whose memory they held in reverence. To maintain their cohesion, those families admitted as chief the firstborn of the firstborn of the firstborn of a far distant founder.

King Philip the Fair and his family in a 14th century manuscript |

So, little by little, small familiar “monarchies” were constituted, based on a leadership transmitted hereditarily, a principle that would endure in almost all the monarchies of the West.

A chief ruled over all the members of the family. Under him were sub-chiefs who ruled branches of the family. So, within a large family there was a kind of federative system, as for instance, in our Brazilian federative system, where the governor of a State is independent but ultimately answers to the President. That is, there were different types of autonomous powers inside that larger group which was the family.

What should we call the chief who was the firstborn of the firstborn of the firstborn? We should call him by a beautiful name: patriarch. Pater in Latin means father. Arch in Greek is the one who governs. A monarch is a single man who governs an entire political body. A patriarch is one who, as a father, governs a large social, rather than political, unit. He is the founder or the one who has the power of the founder. He is the Adam of that world of which he is the head; he is the founder, the father, and in him also is the seed of a king.

Strasburg (town at the crossing of roads), is situated

near the encounter of Ill River with the Rhine |

Many rural states were constituted around patriarchates which dominated certain areas under the central authority of a chief. Many medieval cities,

as I have mentioned, spontaneously grew up for similar reasons around castles and convents, or at crossroads or where rivers meet, sites where it was easier for persons from different places to gather, exchange news, and engage in a simple commerce.

Gradually this system triumphed on the European side of the Mediterranean basin.

The patriarchal Roman society

This analysis of the source of authority in the Middle Ages raises a question: Was this type of patriarchal society characteristic only of the medieval man, or did it exist before then?

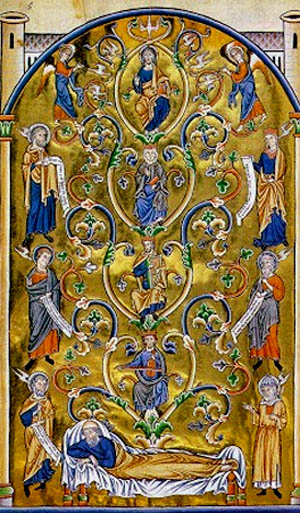

The Old Testament Patriarchs encircling

the ancestors of Christ who sprout from the root of Jesse |

Before the Middle Ages many peoples were led by patriarchs.

We could certainly look at the Jewish people, which from its beginning followed the patriarchal system. The Bible speaks of patriarchs from Adam to Abraham, Isaac and Jacob. They were the seed of a perfect system for the Jewish people: theocracy, which unfortunately did not develop.

As is known, the Jewish people found it too hard to be governed by God through Patriarchs and Prophets. Moved by human respect, they chose to follow the example of the other peoples. They asked for a king to govern them, instead of God. So, they abandoned that first plan, rejecting the governance of the Patriarchs and Prophets. Consequently their monarchy – even with outstanding kings such as David and Solomon – was not the tree that should have been born from that first seed. The Jewish example of patriarchate, therefore, is incomplete for our purpose.

An example closer to our topic is the formation of Roman society.

French historian and sociologist Fustel de Coulanges wrote a famous work, La Cité Antique [The Ancient City], in which the city is synonymous with the whole social-political reality. In this very interesting and informative book, which I recommend, he describes the formation of Roman society.

He shows us how Rome in its early days was familiar and patriarchal. The members of those few initial families venerated the chief, or head of the family, and followed him religiously. When he died, they would make a small statue of him to keep his memory alive and pay him their respects. With time, each family had some of these familial statues to venerate.

A Roman patriarch carries the busts of family ancestors in a public procession |

This veneration of the ancestors, however, went astray and gave rise to the worship of minor deities called the lares gods, the gods of the home place. Such gods were supposedly the protectors and guides of the family. Each family had some of them. Notwithstanding idolatry, which is a very bad thing, the Roman society, with its original veneration for its patriarchs, was established on a familiar and patriarchal foundation.

Those first Roman families living in Rome – legend and poetry tell us that there were seven first families on the seven Roman Hills – felt the need to unite in order to protect themselves. Each family had its own patriarch who represented it in a new ensemble that would one day become the Roman Senate.

In the first phase of their history, that ensemble of Roman patriarchs chose monarchy as a form of government and elected a king. After a while, however, the king wanted to govern on his own, without sharing the power with the other patriarchs or taking their views into consideration.

At the same time, the small Roman army started to be victorious over many adversaries. The city of Rome grew, and many foreign people who did not belong to those initial families came to live in it. These outsiders who came from far and wide understandably were not allowed to enter that familiar structure that gave origin to the city. I am not talking about slaves, but about those free men who came to live in Rome to make a living, establish commerce, study, enlist in the army, etc. They received the name of plebeians, to distinguish them from the Roman people, the members of those large families.

The outsiders who tried to enter the patriarchal structure to have a part in governing the city were not allowed to do so, a normal reaction of self-defense of those first families. This produced resentments, and the plebeians were habitually a force that fought against the patriarchal structure.

So, two forces appeared against the Roman patriarchate, on the one hand, the king and his cohorts, on the other hand, the plebeians.

The fighting between the patriarchate and those two forces escalated during the period of the seven Roman kings. The last king was killed by the members of the Senate, and a new regime – the Roman Republic – was established under the hegemony of the Roman Senate.

Patriarchs or patricians at the Roman Senate |

Members of the Roman patriarchate were also called patricians, a name that comes from the same origin, pater. As the population of the city grew, the patricians organically constituted an aristocratic class. The history of early Rome shows us that the kings united with the plebeians to fight against the patriarchal structure.

Something similar happened under Louis XIV. At that time you also find that the King united with the plebeians to destroy the French organic nobility and its feudal structure. The many complaints against Louis XIV found in the famous Memoirs of Saint-Simon, who was a Duke and a noble, were made because the King was destroying the organic structure of France. Louis XV and Louis XVI followed the same path. Thus History repeats itself.

In The Ancient City, Fustel de Coulanges presents the Roman Monarchy as a bad experience, and the Roman Republic as the regime that actually represented that organic structure of the patriarchs. I agree with him. As long as the Senate remained linked to the patriarchal structure, Rome was following the Natural Law.

Posted October 8, 2007

| | Prof. Plinio |

Organic Society was a theme dear to the late Prof. Plinio Corrêa de Oliveira. He addressed this topic on countless occasions during his life - at times in lectures for the formation of his disciples, at times in meetings with friends who gathered to study the social aspects and history of Christendom, at times just in passing.

Atila S. Guimarães selected excerpts of these lectures and conversations from the trancripts of tapes and his own personal notes. He translated and adapted them into articles for the TIA website. In these texts fidelity to the original ideas and words is kept as much as possible.

Related Topics of Interest

The Dream of a Catholic Empire and the Medieval Wars The Dream of a Catholic Empire and the Medieval Wars

Feudalism and the Modern State Feudalism and the Modern State

Vocations of the European Peoples Vocations of the European Peoples

The Organic Formation of Feudalism The Organic Formation of Feudalism

Overview: Revolution and Counter-Revolution Overview: Revolution and Counter-Revolution

What is Organic Society? What is Organic Society?

The Decline of Feudalism and Growth of the Modern State The Decline of Feudalism and Growth of the Modern State

Departure for the Crusade: A Desire for Sublimity Departure for the Crusade: A Desire for Sublimity

Groups of Friends and Guilds Groups of Friends and Guilds

|

Organic Society | Social-Political

| Home | Books | CDs | Search | Contact Us

© 2002- Tradition in Action, Inc. All Rights Reserved

|

|

|