|

World History

Departure for the First Crusade

Plinio Corrêa de Oliveira

Excerpt by Montalembert:

The great Pope Urban II did not spare any effort to execute his plan of a Crusade in the East. The most valiant chivalry of Europe and the most zealous champions of the Church made haste to answer his call. Nothing was more admirable than that unstoppable resolution of the Pontiff and the response of the Catholic world. The shout “God wills it!” [Deus vult!] in reply to the words of Urban II at Clermont echoed from one end to the other of Christendom, and Europe was shaken by a strong wind that blew out all discords and sowed in souls a desire for sublimity and grandeur which no one could resist.

A kneeling crusader, before setting out on the First Crusade |

Not only Princes and knights, but also peasants and servants rose en masse to go against the infidels. The wealthy and poor, men and women, old men and youths, all sold everything to make the expedition of God. We saw how those who ridiculed it on the eve, drawn by the force of example, became enthusiasts of it the next day. As the simple peasants went on their way in oxcarts carrying all their belongings and even their children, each time a city or a castle would appear on the horizon, they would naively inquire if it were Jerusalem.

All were taken by a sweet thirst for pilgrimage. The nobility in particular showed religious recollection and gravity in their dispositions before leaving the homeland.

Etienne, Count of Blois, wrote in a document to the Abbey of Marmoutier, “As I await prepared to leave at the signal given by the Roman Pontiff, I want to give to this monastery the forest of Lôme in honor of my father Thibaud, whom I fear I have often offended during his life, which is cause for my constant sorrow when I recall it with my wife, friends and servants.”

Raymond, Count of Toulouse, the most powerful among the Princes who took part in the first Crusade, declared he took the Cross for the love of St. Giles, whose monastery he had offended. Godefroy of Bouillon, illustrious leader of the crusaders, brought with him Benedictine monks to sing the Divine Office day and night during the military expedition.

These and other moving scenes from the departure for the Holy War and everything that was realized in it gave this chapter of History this most beautiful name of a deed carried out by man’s hand: Gesta Dei per Francos– the epopee of God made by the Franks.”

(Excerpts of Les Moines d’Occident, Paris: Victor Lecoffre, 1882, vol. 7, pp. 149-158)

Comments of Prof. Plinio:

You can see by the narration of Montalembert that the ideal of Crusade raised by Blessed Urban II had been an object of mockery shortly before he spoke out on it in Clermont. But from the moment he preached the Crusade, a profound and sudden transformation occurred in the spirit of Europeans like a fuse of gunpowder. The change, as Montalembert points out very well, was a desire for sublimity and grandeur, which induced the Europeans to make every effort to liberate the Sepulcher of Our Lord Jesus Christ.

What is this desire for sublimity and grandeur? It is a disposition of soul that we can discern by its effects. Naturally those men, like all men, had attachments to their families, belongings, social situations and their own lives. They left everything behind in order to pursue that ideal. We should not imagine that the crusader was made of a material different than we. He was conceived in original sin, as we are. He only had the advantage of not having inherited the revolutionary spirit that we have, because then the Revolution did not exist. But the rest was the same. To abandon all these things was a great sacrifice for him.

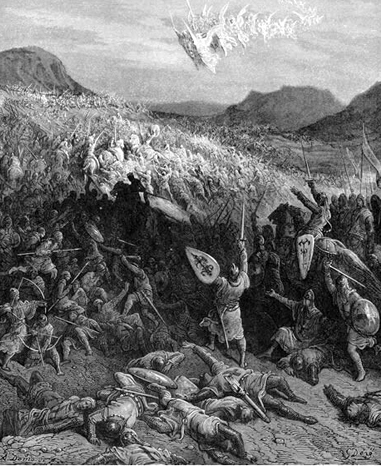

The knights who took the cross understood the brutal deaths that could await them |

You can imagine a man who left a castle, a stable situation, a luxurious life, and went to the East. He was not going on a pleasure trip or sight-seeing. He was going to face death, death as persons at that time knew it. That is, he could have his head split by a blow of an axe, or a spear could enter his mouth and exit the other side of his skull. Or he could fall to the ground in the shock of two cavalry charges and be trampled by horses that could smash his face, tear out his eyes, and leave him agonizing for hours on the ground, blind and unable to hear what was going on in the battlefield. All were aware that this kind of death could be awaiting them.

Nonetheless, from one moment to the next, they all acquired a desire of grandeur. What kind of grandeur? It was not earthly, but heavenly grandeur. They received a grace to understand that the values they were going to defend were enormously higher than the individual concerns of each one. They understood that for love of those values they should sacrifice everything to which they had attachments. That desire for grandeur and sublimity was the great surprise that fell from Heaven.

So, one can understand how all of Europe went on the Crusade. It was not just the nobles who went. It would be normal for the nobility to go because it was the warrior class. It had the moral obligation to fight to liberate the Sepulcher of Our Lord. But the plebeians also wanted to go. They did not have an obligation to fight, except in very exceptional circumstances. Both the nobles and plebeians were moved by that grace and left everything they had to be a part of that glorious fight.

The peasants and their families who set out would ask, with that charming naïveté characteristic of the Middle Ages, if the next city was Jerusalem. We can see that they were not in the habit of leaving their villages and had a vague, confused notion of the long distance they would have to travel and no knowledge of the dangerous seas they would have to cross.

Montalembert also points out the deep recollection of the nobility, its piety and religious spirit. This was the correct spirit of Crusade that unfortunately was lost in the next Crusades. Later, nobles would go on the Crusade principally for appearances and to make good figures at court, where they would praise their own deeds on their return. The first Crusade was principally a religious movement. Some examples were described: the acts of contrition, the spirit of penance, and the reparations offered before leaving for a trip that could be the last.

So, one noble donates a forest to a monastery and in the document that perpetuates his generosity, he also wants it registered that he committed a sin against his father and the donation was to repair for that evil. He did not have to record his transgression, but he did so as an act of humility before posterity. This is the real spirit of penance that the medieval man had and that we have lost. At the very hour that he offered everything to fight for God, he did not boast about what he was doing; he felt sorrow for the sins he had committed before.

Godefroy de Bouillon - Hofkirche, Insbruck |

The medieval sinner had the moral sense of the gravity of his sins. And he wanted his fellow countrymen, who had the same moral sense, to know that he was sorry for those sins and that he was leaving on pilgrimage to pay for them. That collective moral sense was characteristic of an epoch effectively under the kingship of Christ. The good had all the rights and the evil, when it existed, was ashamed of itself. Today we have the very opposite.

It was also very characteristic for Godefroy of Bouillon to take monks with him so that the Divine Office would be sung continuously, as in a monastery. That is, he had an ambulant monastery. You known that the monks have a delegation from the Church. When they sing the Divine Office it is an official prayer of the Church, and not just a private prayer of some monks. It is the whole Mystical Body of Christ that prays through the lips of the monks. Godefroy of Bouillon wanted to have the constant prayer of the Church with him as an assurance that his military efforts against the Arabs would be blessed.

You can imagine the harmonic and complementary contrast: thousands of mounted knights in their armor and helmets who rode along praying together with those monks asking God to bless their weapons. It was a way to move God by so much heroism allied with such great piety in order to win the grace to liberate the Sepulcher of Our Lord.

If a man with the revolutionary mentality of our times had been present then, he would have reasoned in this way: “Since it is in Christ’s interest to liberate His own Sepulcher, why should we pray asking Him to help us to do so? On the contrary, He should support us because His own interest is at stake. We are already doing a tremendous thing by fighting for Him. He should do His part, therefore, and send a troop of Angels to help us win.” This is the revolutionary and bourgeois mentality that imagines God as a business associate who should carry out his part of a contract.

The medieval spirit was different. Since God is infinite, perfect and most holy, He deserves everything. When we give to Him, we are just giving back what was already His. Everything we give to Him is not enough. He does not owe anything to any man. Therefore, man must fight for Him with a humble spirit, with the conviction that he, man, is the one who has received the advantage. Hence we can understand the great care of the crusaders to pray to God so that He would favor the effort of their arms. This is the true spirit of humility. To recognize that every good we have comes to us from God through Holy Mother Church.

We live in an epoch where it is not only the Sepulcher of Christ that was desecrated; rather, the Catholic Church herself is occupied by Progressivism, an evil that is a thousand times worse than Islamism. In this epoch, we should have a great Crusade to re-conquer the Holy Church from her enemies. Let us ask Our Lady to give us a grace similar to that which she gave to the first crusaders, so that we will forget our own interests and care only about the liberation and glorious restoration of the Roman Catholic Church.

Posted on October 9, 2006

Related Topics of Interest

Understanding the Crusades Understanding the Crusades

A Counter Crusade and New Notion of Infallibility A Counter Crusade and New Notion of Infallibility

Blessed Urban II Blessed Urban II

Debunking Myths about Life in the 1500s Debunking Myths about Life in the 1500s

The Swan's Song of Galileo's Myth The Swan's Song of Galileo's Myth

The Immaculate Character of the Church The Immaculate Character of the Church

How a Catholic Should Act in face of Bad Popes How a Catholic Should Act in face of Bad Popes

Related Works of Interest

|

History | Home | Books | CDs | Search | Contact Us | Donate

© 2002- Tradition in Action, Inc. All Rights Reserved

|

|

|