|

Socio-Political Issues

Defining the ‘Left’ and the ‘Right’

Plinio Corrêa de Oliveira

The words “right” and left” are currently used to describe positions taken on varied themes. Their use commonly relates to political, social or economic matters, literature and arts, but also to ways of feeling or being. The terms have such diverse meanings that many observers claim they have lost any value to classify ideological, cultural or moral positions.

Regardless of the talent, culture and notoriety of those with this opinion, “right” and “left” have continued to be commonly used terms and are indispensable for ideological analysts.

This fact seems to demonstrate there is something substantial and authentically expressive at the very core of these terms. Therefore, they cannot be so simply disregarded, at least not until common usage consecrates other words to replace them.

I propose to make a brief analysis here of this “something substantial” to check with my readers whether my feeling about these terms corresponds to theirs, as well as to that of the general public.

I begin by noting that not everything is imprecise in the meaning of these two words. There is one clear zone that can be defined. Then, after showing this, we can detect the connecting thread that will lead us, step by step, through the more ambiguous meanings to a final clarification of what is meant by “right” and “left.”

Left: Radical acceptance of the ideals of the French Revolution

The clear zone is in the word “left.” One need only think of the trilogy of the French Revolution: liberty, equality and fraternity. To this day, the general consensus describes the perfect leftist as one who defends not just any liberty, equality and fraternity, but a total liberty, a complete equality and an almost universal fraternity.

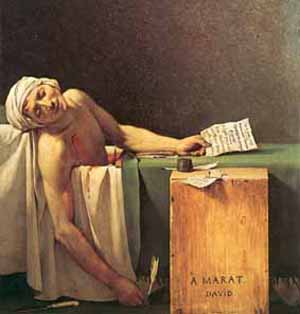

Marat's position, the extreme of the French Revolution radicalism, represents the entire left |

In short, he would be an anarchist in the etymological and radical sense of the word (from the Greek an – without – and arche – government), with or without the connotation of violence or terrorism.

Moderate leftists consider the dream of the radical leftist as utopian (it is “unfortunately utopian,” they say). None of them would deny, however, the full leftist authenticity of this utopia. If this is the pole of absolute leftism, then it is easy to discern how – on the leftist scale – a program or method can be described as being more or less leftist. Its classification derives from its distance from that total Anarchism.

For example, the more a socialist is leftist, the broader and more operational is the equality he demands. One who demands total equality will be totally leftist.

A similar appraisal can be made about another “value” of the 1789 trilogy. I refer especially to political liberalism. The more a person calls for total liberty, the more leftist he is.

Of course, there are certain contradictions between Socialism and Liberalism that lead to objections to what I have just affirmed. One such objection is that economic totalitarianism can easily destroy political liberty, and vice versa. But this contradiction exists only in the intermediary stages before total Anarchism is reached. Neither Socialism nor Liberalism represents total

Anarchism, although they can both prepare the way for it. For one can reach total Anarchism either through absolute liberty or, more often the case, through absolute equality.

Absolute equality is more readily adopted by those who are less or have less against those who are more or have more. Complete liberty, in its turn, results in the denial of all authority and, therefore, all law. These two ways that appear so different are not parallel roads that run infinitely without ever touching. However contradictory they may appear to today’s moderate, they converge at a final anarchical point, where one meets and completes the other.

Thus, according to the general consensus, leftism has a well-defined goal and scale of “values.”

The true right defends proportional, harmonic inequalities

The question then turns to whether the “right” also has a well-defined goal and values.

Here there is undeniable confusion. We need to find a connecting thread – like that which we found on the left – which will lead us step by step toward classifying the subtle nuances of rightism.

Justice lies in harmonic and proportional inequalities |

The words “right” and “left” surged in the political, social and economic vocabulary of 19th century Europe. Leftism was an ideological participation in the thinking and work of something still new and quite defined in its general lines, that is, the French Revolution. The left was not only a volcanic negation of a tradition that appeared to be dead, but also the affirmation of an inescapable future. In face of this devastating Revolution, the right has only gradually come to define itself – in an undecided and contradictory way (cf. Michel Denis, Les Royalistes de la Mayenne et le Monde Moderne, Publications de l'Université de Haute-Bretagne, 1977).

What, in the full rigor of logic, would be the right, if it were defined as anti-leftist and a fortiori as anti-anarchist?

As I already noted, total Anarchism affirms that each and every inequality is unjust. Thus, the less the inequality, the less the injustice. Liberty is dear to Anarchism precisely because authority is in itself a denial of equality.

On the other hand, rightism affirms that inequality in itself is not unjust. Rather, in a universe where God created all beings unequal, especially men, injustice would be imposing an order of things contrary to the one that God, for the highest reason, made unequal (cf. Mt. 25:14-30; 1 Cor. 12: 28-31; St. Thomas Aquinas, Summa contra gentiles, Book III, chap. 57).

Thus, justice lies in inequality.

In passing, let me note that from this basic truth one cannot deduce that the greater the inequality, the more perfect the justice. For leftism, the antithetical affirmation is logical (e.g. the greater the inequality, the greater the injustice). There is, however, a flagrant difference between the leftist and rightist perspectives.

The rightist knows that the inequalities God created are not terrifying and monstrous, but proportioned to the nature, well-being and progress of each being, as well as appropriate for the general ordering of the universe. This is the Christian inequality.

Similar considerations could be made about liberty in the universe and in society.

It is important to understand that the standard of rightism is not an absolute inequality, symmetrically opposed to absolute equality. It is a harmonic inequality. The more a doctrine opposes the trilogy of 1789 and comes closer to this standard of harmonic and proportional inequalities, the more it will be rightist.

Those thinkers or men of action who rose up the 19th and 20th centuries against the Revolution were called rightists only for this reason. But they not always understand this important rule of rightism. They – or those who studied them – imagined at times that the label of rightism could justify abysmal inequalities (political, social and mostly economic), as if the extreme right position coherently were this.

False right and true right

Franco, although adopting a few points of Christian rightism, was fundamentaly a National Socialist |

Other “rightists” made concessions to the egalitarian spirit because they were themselves infected by the revolutionary principles they were combating. Or they made concessions for tactical reasons to protect their power or gain it. We see this in the official socialist character of Fascism, and in the unofficial but evident nature of Nazism.

For these reasons, the term “right” was much less clearly defined than “left” in current language. It came to designate not just the true rightism of a sacral, hierarchical and harmonic Catholic inspiration, but also “rightisms” modeled in part by some Christian traditions and in part by some atypical ideological principles (and experiences).

What seems certain to me is that even though certain so-called rightist currents have had socialist notes, the current language nonetheless only calls them rightist because it supposes they have a greater or smaller affinity with the ideal Christian rightism that I described above. This ideal, through a centuries-old tradition, entered the consciousness as well as the sub-consciousness of everyone.

In summary, there are defining marks for both the right and the left, and a whole gamut of intermediary nuanced stages proceeds from them.

Related Topics of Interest

Liberals, Modernists and Progressivists Liberals, Modernists and Progressivists

French Revolution Condemned by the Popes French Revolution Condemned by the Popes

Patriarchs at the Origin of the Middle Ages Patriarchs at the Origin of the Middle Ages

The Organic Formation of Feudalism The Organic Formation of Feudalism

Revolution and Counter-Revolution Revolution and Counter-Revolution

Nazism: A Gnostic Sect Nazism: A Gnostic Sect

Related Works of Interest

|

|

Social-Political | Hot Topics | Home | Books | CDs | Search | Contact Us | Donate

© 2002- Tradition in Action, Inc. All Rights

Reserved

|

|

|