Catholic Customs

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The Wren Boys & St. Stephen’s Ride

Wren Boys singing for alms

Boys hunting the wren

The “Wren Boys” who hunted the birds darkened their faces with burnt cork or put on straw masks. When they found a wren in the bush and scrub they shouted out and made a commotion. The most traditional manner of killing the wren was by stoning in memory of St. Stephen’s death. (4)

Alms boxes in the Roche Abbey, England, 1950

The first and most ancient verse of the traditional song, which was nearly the same in every area, goes as follows:

A group of Irish Wren Boys in the 1950s enjoy a glass of wine after performing the wren song

On Stephen’s Day the bird was caught.

He is small himself, his family is great,

And if he gets an oaten cake, he will make a dance.(5)

Sometimes the Wren Boys performed a mummer’s play or were accompanied by a piper, fiddler or expert trickster and tumbler. If two different parties of Wren Boys met, they had a contest to see which group would get the bird. After making their rounds, the Wren Boys in the Isle of Man closed the day by placing the wren on a bier and carried it in a funeral procession to a graveyard where they buried him while singing their ancient funeral dirges. (6)

St. Stephen & the horses

St. Stephen’s patronage also extends to horses. The Germans call this feast day der grosse Pferdstag (the great day of the Horse). (7)

It is uncertain why St. Stephen is so closely associated with horses. A 10th century poem tells a tale of St. Stephen owning a horse that was miraculously cured by Our Lord, but this does not fully explain the patronage.

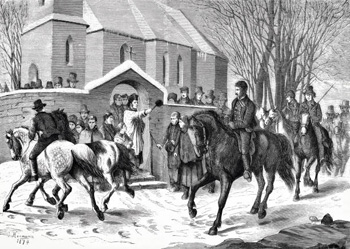

A priest blesses the horses on St. Stephen’s Day

But a better hypothesis proposes that Stephen’s patronage of horses originated with the honor given to animals in medieval times during the Twelve Days of Christmas when domestic animals were given extra food and rest from work. The horse, being the noblest domestic animal, was naturally given a feast of its own on St. Stephen’s Day. (9)

Hitching up the horses for a sleigh ride

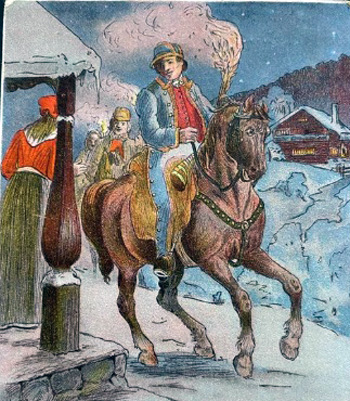

In Poland and other Eastern European countries, the people feasted on special sweet rolls in the form of horseshoes (podkovy or St. Stephen’s Horns) when they arrived home. Later in the day, the horses were hitched to a wagon or sleigh for the “St. Stephen’s ride.” (11) In Finland, every family was obliged to open its home to the passengers of any sleigh that stopped by their house.

In some areas of Sweden, masters had their servants mount their horses and ride them to the nearest north-flowing water source; there the horses were obliged to drink to assure them of good health in the coming year. (12)

Above, Stephen Riders in Sweden;

below, Hungarian men in a horse race

Farmers also brought sheaves of oats and hay along with water and salt to be blessed with their horses; hence the French name for the feast: “Straw Day.”

Polish peasants used kerchiefs to tie their oat sheaves specially chosen from those standing in a corner of the dining room during the Christmas Eve meal. After the sheaves were blessed, the people threw oats and peas at each other and at the priest, in remembrance of the stoning of St. Stephen. (14)

These blessed provisions were preserved and some were fed to the horses as a protection against accidents and sickness. (15) In some places, a portion was also fed to the cows and chickens to protect them from disease, and the rest was saved and mixed with the seed grain to bring blessings upon the coming year’s sowing. Some families even hung bundles of the oats in the house to ward off fire and lightning.

In England, there is an ancient custom believed to have originated with the Danes of bleeding horses (and sometimes cattle) on this day to preserve them from sickness in the coming year. Up until the modern era, most farmers and tradesmen with horses scrupulously followed this custom, being sure to bring their horses to a sweat in a full gallop before the proceedings. (16) Even in Rome, the Pope’s horse was bled and the blood was reserved to be used in the treatment of many disorders. (17)

Thus did the blessings of St. Stephen’s sacrifice descend even into the animal kingdom. Our Catholic forefathers were mindful of Stephen’s presence in many ways on his feast day and delighted in receiving the blessings that the Church bestowed on the noble steeds that were so vital for their daily lives.

A family sleigh ride on St. Stephen’s Day

- M. A. Courtney, Cornish Feasts and Folklore (Penzance: Beare and Son, 1890)

- Steve Roud, The English Year (Penguin Books: 2006), pp. 408-410.

- James Mooney, “The Holiday Customs of Ireland,” Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 26, No. 130 (Jul.- Dec., 1889), p. 417.

- https://www.irishcultureandcustoms.com/ACalend/StStephens.html

- J Mooney, “The Holiday Customs of Ireland,” p. 418.

- T. F. Thiselton-Dyer, British Popular Customs, Present and Past; Illustrating the Social and Domestic Manners of the People (London: George Bell and Sons, 1876), p. 495.

- William S. Walsh, Curiosities of Popular Customs and of Rites, Ceremonies, Observances, and Miscellaneous Antiquities (Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott Company, 1898), p. 900.

- A Celebration of Christmas, ed. Gillian Cooke (New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1980), p. 129.

- Francis X Weiser, The Holyday Book (London: Staples Press Limited), pp. 137-138.

- Bonnie Blackburn and Leofranc Holford-Strevens, The Oxford Companion to the Year (New York: Oxford University Press, 1999), p. 533.

- Evelyn Birge Vitz, A Continual Feast (San Fransisco: Ignatius Press, 1985), pp. 155-156.

- A Celebration of Christmas, ed. Gillian Cooke (New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1980), p. 130.

- Elisabeth Luard, European Festival Food (London: Bantam Press, 1990), p. 74.

- Sophie Hodorowicz Knab, Polish Customs, Traditions, and Folklore (New York: Hippocrene Books, 1996), p. 43.

- W. Walsh, Curiosities of Popular Customs, p. 900.

- Steve Roud, The English Year (Penguin Books: 2006), p. 407.

- W. Walsh, Curiosities of Popular Customs, p. 900.

Posted December 20, 2024

______________________

______________________

|

|

|

|

|

|