Catholic Customs

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

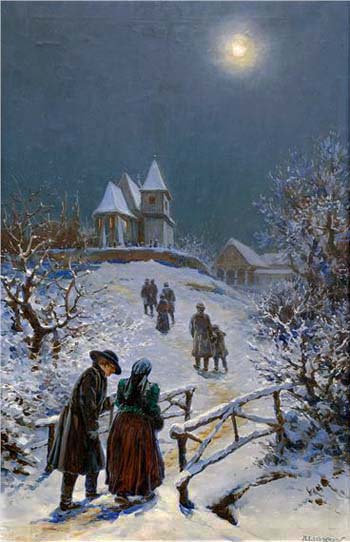

The Flame-lit Journey to Mass

As the hour of Midnight approached in Christendom of old, the desire of every man’s heart was to attend the Holy Sacrifice and gaze upon the newborn Man-God. The joyous peal of church bells cut through the cold air of the winter night and lights appeared on every mountain slope, hill and valley, making villages and cities glisten like hundreds of stars.

These lights were the torches of the people walking to grand cathedrals in picturesque plaza squares or making their way by foot or on sleighs to small country churches tucked amidst farmlands or mountainsides.

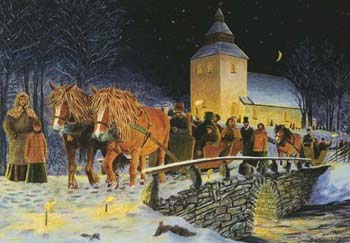

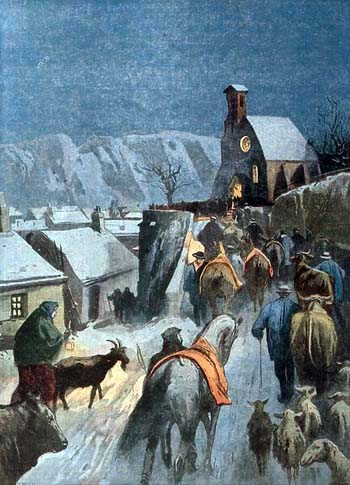

Villagers from Alsace carrying laterns to Mass; below, processing to Midnight Mass with their animals

The Eskimos of Alaska also traveled far through the frozen wilderness to attend the Midnight Mass at the mission chapel, after which the people fervently sang the traditional carols in their native Innuit tongue.

The Scandinavians of old rode in torch lit sleighs through dark forests to travel to the churches where great bonfires burned outside into which the people threw their torches before attending Mass. In the mountainous regions of France, these Christmas bonfires were called "fires of joy."

The cities too were filled with splendid lights. The villagers and pilgrims in the Provençal town of Séguret were guided to the Church of Saint-Denis by an enormous star that hung on a crag over the village. (1)

In Latin lands, the lights took on the vitality of the people. Not content with merely lighting their streets with torches, the Italians and peoples of Latin America illumined the Christmas sky with the blaze of fireworks, while Spaniards illumined the streets with innumerable oil lamps that reflected on the gaily dressed people. (2)

Villagers walking to Midnight Mass, below, brilliantly colored decor in a church in Puebla, Mexico

In the deserts and tropical islands, Catholic peoples adorned their churches and nativity scenes with bright tropical flowers, cacti, colored paper streamers, and colorful candles. In addition to the candles and flowers, the Filipinos often lowered a star from the top of the church during the singing of the Gloria in Excelsis to represent the Star of Bethlehem. In the East, richly woven rugs and tapestries gave special grandeur to the churches. (3)

The hour for all of this brilliance to shine forth was marked by the pealing of the church bells that were especially joyous on this Holy Night, for the Angels were said to assist the bell-ringers. (4) These bells were cherished especially by those who stayed home unable to attend the Midnight Mass; such people in England opened their doors to “welcome Christmas in.”

In some parts of the British Isles during medieval times, the church bells were rung at around 10 o’clock to toll in a funeral tone, one stroke for every year before Christ’s birth. This was known as “tolling the Devil’s Knell” because the people saw it as the funeral peal for the Devil whose demise began at midnight when Christ was born. (5)

From some Austrian churches, the bells were echoed by trumpets that blew a fanfare from the walls and towers of the city. Carols are still played from church towers in Central Europe that send the notes of cherished tunes deep into the quiet night. (6)

The beauty of the Liturgy & pious dramas

When all were assembled inside the beautifully adorned churches, the Midnight Mass began. The Mass became known as La Misa de Gallo (“the mass of the rooster”) in Spain and Spanish colonies, an expression that comes from ancient Rome when the “crow of the rooster” denoted the start of the new day at midnight. This was the first of the three Masses said during Christmas day, and pious Catholics strove to attend all three Masses.

Midnight Mass in Vienna 1853; below, the Canto de la Sibila is the oldest Christmas tradition in Mallorca

Other peoples, however, did sleep, and in order to ensure that they awoke on time men were chosen to awaken everyone. In Ireland, young men awakened the people on Christmas morning with loud salutes and the blowing of horns to call them to the early Mass. (8)

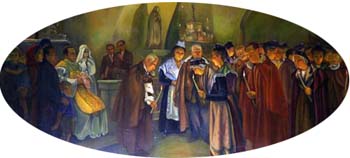

The Medieval Liturgy was embellished with ceremonies that brought the events of Bethlehem closer to the faithful with mystery plays. (See “The Christmas Creche & Mystery Plays”) Remnants of these ceremonies have even survived in some churches to this day.

In Mallorca, Spain, shortly before midnight the longings of Advent are brought to their climax with a reminder of the Last Judgment. A boy of about 10 is elected to play the role of a ‘Sibyl” in which he sings the prophetic hymn of the Sibyl announcing the imminent approach of the fulfillment of the prophecies of old: Jesus Christ, Universal King,

Man and true eternal God,

Will come from heaven to judge

Everyone and administer justice. (9)

Thus, were the Catholics of old reminded of the power and majesty of their Infant King. Every church in Rome and many throughout the surrounding Italian villages devised ways to give this King a fitting homage by erecting beautiful nativity scenes with a richly dressed Bambino (Christ Child) often wrapped in gold and silver tissue studded with gems.

The priest blesses Rome with the bejeweled Bambino

This ceremony, continued in many areas to this day, is the grandest in the Church of Santa Maria in Ara Coeli where a statue of the Santo Bambino is kept that was carved from olive-wood from Gethsemane by a Franciscan friar in Jerusalem at the end of 1400 and was painted by the hand of an Angel.

On Christmas Day, the statue clothed in silk and jewels is carried in procession to the top of the flight of steps that overlooks the square of Ara Coeli where the priest blesses the people with the Santo Bambino. Throughout the Christmas season, the Santo Bambino remains on His “throne” in the lap of a statue of Our Lady that rests in the midst of a lavishly decorated Nativity Scene in a side chapel. (11)

These endearing ceremonies in Rome gave inspiration to the rest of the Catholic world. In many churches, a statue of the Christ Child was laid in the Manger before Midnight Mass and the faithful were delighted in singing carols to the Infant King.

Shepherds processions

Many shepherds throughout Christendom processed with their sheep to the church on this night. Even to this day in the Basque village of Labastida, 12 shepherds wearing their festive pelts processed to the Nativity Scene before the town hall to sing carols and perform their traditional “Danza de los Pastores” (Dance of the Shepherds), using their staffs to pound the ground at specified intervals.

French shepherds processing to Midnight Mass; below, Danza de los Pastores in Labastida

Pyrenean shepherds dyed their rams’ fleeces bright colors and tied lighted candles to the ram’s horns. On arrival at the church, the shepherds taught their rams to kneel before the Crèche. (13)

The villagers of the ancient French town of Les Baux had a candlelit procession on Christmas Eve led by villagers dressed as the Holy Family, the shepherds, the Three Magi, the Angels and pilgrims.

At the Offertory of the Mass, the head shepherd of the town would lead a ribbon-bedecked ram to the altar pulling a cart adorned with candles, tinkling bells, flowers and greenery. Inside the cart was a spotless lamb.

Concluding the procession was a villager dressed as Our Lady, who presented a wax image of the Christ Child to the priest. He held this image uplifted in his arms as the shepherds and the Three Magi came forward to venerate the Christ Child.

Lastly, the lamb was taken from the cart and presented to the Christ Child. At the Consecration, the head shepherd pulled the lamb’s tail so that the bleating of the lamb would blend with the ringing of the bells to simulate the cries of the Child Jesus in the cave at Bethlehem. (13)

Moved by the noble sentiments of these ceremonies, Catholics assisted at the Midnight Mass with fervor. When Mass ended, everyone joyously returned to their own homes to make merry – for the long awaited day had finally arrived. Christmas had officially begun!

Continued

The head shepherd of Les Baux offers

his newest born lamb to the Christ Child

- Christmas in France (Chicago, Illinois: World Book-Childcraft International, 1980), p. 52.

- Dorothy Gladys Spicer, Festivals of Western Europe (New York: The H. W. Wilson Company, 1958), p. 218.

- James L. Monks, Great Catholic Festivals (London: Abelard-Schuman Ltd., 1958), p. 13.

- WM. Hackwood, Christ Lore: Being the Legends, Traditions, Myths, Symbols, Customs and Superstitions of the Christian Church (London: Elliot Stock, 1902), p. 47.

- Steve Roud, The English Year (Penguin Books: 2006), p. 370.

- Francis X. Weiser, The Christmas Book (New York: Harcourt, Brace and Company, 1952), p. 53.

- Dorothy Gladys Spicer, Festivals of Western Europe (New York: The H. W. Wilson Company, 1958), p. 218.

- https://www.irishcultureandcustoms.com/ACalend/XmasthenNow.html

- Nina Epton, Spanish Fiestas (Cranbury, New Jersey: A. S. Barnes and Company, 1969), p. 212.

- Dorothy Gladys Spicer, Festivals of Western Europe, p. 113.

- Mary P. Pringle and Clara A. Urann, Yule-tide in Many Lands (Boston: Lothrop Lee and Shepard Co., 1916), pp. 141-142.

- https://xn--espaaenfiestas-tnb.es/fiestas-espa%C3%B1a/fiestas-pa%C3%ADs-vasco/fiestas-%C3%A1lava-araba/fiestas-labastida-bastida/fiesta-pastores-labastida-bastida.html

- Violet Alford, Pyrenean Festivals: Calendar Customs, Magic and Music, Drama and Dance (London: Chatto and Windus, 1937), p. 57.

- Dorothy Gladys Spicer, Festivals of Western Europe, p. 61; Christmas in France, p. 51.

Posted December 13, 2024

______________________

______________________

|

|

|

|

|

|