Catholic Customs

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

St. Stephen's Day - 1

Alms Boxes & Gift Giving on the

Second Day of Christmas

St. Stephen’s Martyrdom:

Book of Hours of Simon de Varie

The herald of truth; the first witness of Christian grace;

The living foundation-stone,

And ground-work of martyrdom.”

(Hymn from an ancient Roman-French Breviary

This great Proto-Martyr received due honor in medieval times through the special privileges bestowed on deacons during his feast of December 26. In many churches, deacons fulfilled every office that was not beyond their order: they were the chanters and choristers, and the Epistle relating the history of St. Stephen’s death was sung by a deacon. (1)

Alms boxes & gift giving

While the Church thus gave special honor to the diaconate, all of her children were inspired to manifest in the celebrations of this second day of Christmas their zeal for the great Arch-Deacon by imitating his generosity towards God and neighbor through generous almsgiving.

St. Stephen giving alms by Fra Angelico; below, prominent members of Aldeia Viçosa, Portugal, announce the day while men prepare to throw chestnuts to the crowd from the tower

Farmer’s wives often baked pies for their farm workers. People from the North Riding of Yorkshire baked many large goose pies on this day and distributed all but one to their poor neighbors, the one pie being saved for the family to eat on Candlemas. (4)

Norwegians had an old tradition that required any passer-by (young or old, rich or poor) to stop at every farmhouse that he passed on this day to partake of food and drink. (5) Every household offered hospitality. Throughout the Germanic lands, people drank to each other the “Stephen-Cup” for good health, while the Finns traditionally exchanged food, wine and clothing amongst their neighbors on this day. (6) In Austria, married children visited their paternal homes to perform the ancient ritual of cutting the Störi (special bread seasoned with anise seed). (7)

The Italians and Portuguese shared roasted chestnuts with each other on this feast. In Aldeia Viçosa, a wealthy Portuguese matron left a perpetual income to her parish church to be used to purchase chestnuts and wine for the poor on the day after Christmas with the request that all who should receive these gifts should pray for her soul.

The parish has continued this even to this day, although her name has been forgotten and she is referred to simply as the “Old Woman.” Chestnuts are thrown from the top of the church tower and the poor scramble to collect the gifts. (8)

An alms box in the Roche Abbey, England, 1450

Then a few days before Christmas, carrying their Christmas boxes they made rounds to the houses of patrons to receive their generous offerings. By St. Stephen’s Day, their boxes would be filled, so they broke the boxes and counted the money, which was often used to buy presents for their friends and family. This custom led to St. Stephan’s Day being named “Christmas Boxing Day” which was shortened to “Boxing Day” in England.

Germany and Holland had a similar custom whereby children stored extra money that they had earned in earthen pig-shaped boxes. On Christmas, they were permitted to open the “feast pigs”: from this originated the “piggy bank” of today. (9)

Often the employers gave extra money to their laborers or servants on this day. This gift would often be used to have Masses said, for this was a great privilege that the poorer classes could only afford with much difficulty.

One scholar suggested that Christmas boxes may have originated with ship chaplains who carried Christ’s Mass boxes on board to collect money for masses that would be said for the safety of ships taking long voyages. (10)

If the ship had no chaplain, a priest of the crew’s home parish put a box on the ship. Crewmen who wanted to ensure a safe return would drop money into the box, which was then sealed and kept on board for the entire voyage. Upon safe arrival on land, the box was given to the priest who offered a Mass in thanksgiving for the successful voyage. (11)

A day of public visits & communal celebrations

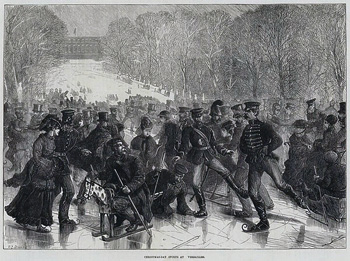

Ice skating on a large ice rink at Versailles in the 1800s

There’s no fast at his Even.

Throughout Christendom, the second day of Christmas was the day on which families left their homes to visit friends and neighbors, attend village dances, and enjoy other forms of merrymaking in the community. Caroling reached its height at this time. Indeed, this was a fitting day to bring the joy of Christmas into the public for it commemorates the Saint who was one of the first to preach about the Savior.

Before dawn in Swedish villages, “Stephen’s men” traveled through the streets singing traditional Stephen’s songs (Stafansvisa) to awaken the villagers and receive ale as a reward. (11) In Transdanubia, Hungary, the village boys also processed on this day singing traditional songs: “We have come, the servants of St. Stephen.” (12)

In addition to caroling, people everywhere engaged in folk dancing and outdoor sports (especially ice skating, sledding and skiing in the northern countries).

A Swedish family dances in a ring

around their Christmas tree

It's Christmas again, it’s Christmas again,

And Christmas lasts until Easter!

But that wasn’t true, no, that wasn’t true

Because in between comes Lent!

Processions and dramatic reenactments were also popular on this feast. In Baiano, Italy, the woodcutters and young men of the village hewed down a large chestnut tree and drew it on a cart into the church piazza where it was blessed by a priest. Wood was then piled around the tree, and as it was ignited, rifles fired and music filled the air. Once the fire had died down, the ashes were sold to those who made soap and home remedies, and the profits given to the poor. (14)

In the small Portuguese village of Ousilhão, men were chosen to be the officers of the festival of St. Stephen. One man was the “king” and he was accompanied by two “vassals” and four young men who acted as his “stewards.” Before the Mass began on December 26, the villagers assembled at the “king’s” house and formed a procession to the church.

The Zangarrón walks through the streets clanging the cowbells on his back & begging for his Epiphany gift

In the Spanish town of Sanzoles del Vino, a man dressed as a Zangarrón, went through the streets clanging the cowbells on his back and begging for his Epiphany gift and frightening the children with large pig bladders he held in his hand. He was accompanied by the year’s recruits who joined him in dancing before the statue of St. Stephen in the main square of the village after the Mass. (16)

Thus, all over Christendom the second day of Christmas brought joy and merriment as our Catholic forefathers sought to bring the memory of St. Stephen into the city streets and lonely country sides, so that the mysteries of Christmas that he died defending would penetrate every corner of their small worlds. May the great Proto-Martyr procure for us a similar fervor and joy, so that the Catholic society of old may be restored in our homes and communities.

Christmas caroling

- Dom Prosper Guéranger, The Liturgical Year, vol. II (Fitzwilliam, New Hampshire: Loreto Publications, 2013) p. 412

- https://projectbritain.com/Xmas/boxingday.html

- Elisabeth Luard, European Festival Food (London: Bantam Press, 1990), p. 74

- William S. Walsh, Curiosities of Popular Customs and of Rites, Ceremonies, Observances, and Miscellaneous Antiquities (Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott Company, 1898), pp. 897-898.

- Dorothy Gladys Spicer, Festivals of Western Europe (New York: The H. W. Wilson Company, 1958), p. 170.

- Ann Ball, Catholic Traditions in Cooking (Huntington, Indiana: Our Sunday Visitor, 1993), p. 146.

- http://www.brauchtumskalender.at/brauch-125-stephanitag

- https://www.portugalnummapa.com/magusto-da-velha/

- Francis X. Weiser, The Christmas Book (New York: Harcourt, Brace and Company, 1952), p. 159.

- Walsh, Curiosities of Popular Customs, p. 898; Bonnie Blackburn and Leofranc Holford-Strevens, The Oxford Companion to the Year (New York: Oxford University Press, 1999), p. 534.

- https://projectbritain.com/Xmas/boxingday.html

- A Celebration of Christmas, ed. Gillian Cooke (New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1980), p. 129.

- https://www.arcanum.com/hu/online-kiadvanyok/MagyarNeprajz-magyar-neprajz-2/vii-nepszokas-nephit-nepi-vallasossag-A33C/szokasok-A355/jeles-napok-unnepi-szokasok-A596/december-A912/december-26-karacsony-istvan-napja-A9E6/.

- Lee Wyndham, Holidays in Scandinavia (Champaign, Illinois: Garrard Publishing Company, 1975), p. 86; Festivals of Western Europe, p. 113.

- https://www.portugalnummapa.com/caretos-de-ousilhao/.

- Cristina Garcia Rodero, Festivals and Rituals of Spain (New York: Harry N. Abrams Inc, 1994), p. 273.

Posted December 20, 2024

______________________

______________________

|

|

|

|

|

|