Socio-Political Issues

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

La Pira: A Catholic Communist - Part VI

The Roots of La Pira's Revolutionary Agenda

A brief excursion through the early years of La Pira’s career will bring to light the roots of his political thinking which later blossomed into a utopian agenda that reflected the basic characteristics of the Soviet model – State interventionism and coercion. We need to go back to the ‘20s and ‘30s when Mgr. Montini (the future Pope Paul VI) was the National Chaplain of the Italian Catholic Universities Federation (FUCI). He gathered around him a group of young and ardent radicals, including La Pira, whom he trained up to be not only the future leaders of Italian society, (1) but also the future shock troops of the Vatican II revolution in the Church.

The agenda for Montini’s program had already been set by his close friend and collaborator, Jacques Maritain, whose vision of a democracy based on Integral Humanism Montini adopted wholeheartedly. It was a philosophy that preached respect for secular values and religious pluralism. Its aim was to create a new Christian civilization of universal fraternity in which the laity, freed from ecclesiastical authority (but not, alas, total State control) would work with the help of all who shared “human values” to achieve the “common good.” La Pira drank deeply from this poisoned well which became the source of his whole outlook, as expressed in the many Conferences he later organized to find “the ground of a common, Christian and human civilization.”

The dark art of deception

It is noteworthy that Montini was using his spiritual authority decades before Vatican II to preach this naturalistic world-view to his disciples, deceiving them into thinking that his revolutionary “new civilization of love” was a moral obligation drawn from the Gospels. In so doing, he stood condemned by Pope St. Pius X who had censured in Notre Charge Apostolique those who identified the Gospel with the Revolution. Montini’s student movement was evidently one of those “dark workshops” mentioned by Pius X “in which are elaborated these mischievous doctrines which ought not to seduce clear-thinking minds.”

Mischief and deceit were certainly elaborated in the secret meetings that La Pira attended at the Monastery of Camaldoli (2) just outside Florence in July 1943. It was none other than Mgr. Montini who had inaugurated these study weeks in Camaldoli for his FUCI graduates. (3) Among the participants were some prominent figures who had also been formed in the Montinian mould. These included:

The Code of Camaldoli

With views such as these, it is only to be expected that the plan they masterminded in their cloistered seclusion at Camaldoli aimed to produce a new society based on a coercive system of social control operated by a bureaucratic elite. To this end, they framed the Code of Camaldoli, a document originally named Per la Comunità Cristiana (For the Christian Community), consisting of 99 propositions to change the political, economic and social order in Italy. They claimed that the Code was a “third way” between Capitalism and Communism, that it was based on the social teaching of the Church, and that it was the embodiment of the Gospels.

But an examination of its contents (4) reveals that it had more in common with the spirit of the Manifesto of Equals of Gracchus Babeuf, as its carefully crafted language masked the latter’s cruder calls for “real equality” and an end to social privilege, particularly in relation to private property.

In the ideal “Christian” society sought by La Pira and his confederates, the following stipulations were considered to be in conformity with the Gospels:

Article 11 called for the creation of social conditions to eliminate privilege arising from wealth, social class or education. (5)

Article 11 called for the creation of social conditions to eliminate privilege arising from wealth, social class or education. (5)

Article 71 took “class war” as its point of departure. It affirmed that the ruling principle of economic life was no longer the rights of the individual but “la giustizia sociale” (“social justice”) which was to be achieved by an equal distribution of goods. (6)

Article 76 specifically undermined private ownership of the means of production;(7) if the owner was considered not to conform to the framers’ idea of the “common good,” i.e., if he has used his property to enrich himself, he could have his right to ownership curtailed.

Article 80 recommended State intervention to limit the consumption and use of goods and the accumulation of wealth. (8)

Article 86 aimed at the elimination of “excessive” economic disparities between citizens and at the transmission/distribution of goods among everyone. It accused the minority of rich people of exercising a despotic power over the economy. (9)

Article 88 attempted to justify State intervention in the economy on the mistaken grounds that the State, rather than private owners, can be trusted to produce fairer outcomes (utilità maggiore): wealth should not be left in the hands of individuals (nelle mani dei singoli).

Article 91 was the equivalent of Marx’s dictum “From each according to his ability, to each according to his need.”

Article 93 envisaged the imposition of taxes to soak the rich as the principal means of the redistribution of wealth (10)

There was even a clause to legitimize civil disobedience in matters that conflicted with the Code, and another to encourage the practice of working mothers.

An antithesis of the Gospel

Far from being the embodiment of the Gospels, what all this reflects is a bundle of old prejudices originating in the mindset that produced the French Revolution and was later popularized by Karl Marx. The Code represents a pattern of thinking that emanates from a visceral hostility to private capital and investment and that regards government means of economic organization as superior to free enterprise. If enacted in legislation, it would mean forcibly overriding the voluntary decisions of consumers and savers, violating their property rights and their freedom of association in order to realize the national government’s economic ambitions.

The drive for totalitarian solutions has always exercised a strong appeal among certain groups with a progressivist agenda. The Code of Camaldoli is, therefore, not inspired by the Gospel but by the antithesis of the Gospel – the lust for power not only to rule the kingdoms of this world but to shape them in the image of their own political opinions and prejudices. Unfortunately, this mentality is deeply rooted in the Church and reflects trends that have been accelerating for decades in the ranks of Catholic Action since the publication of Rerum Novarum (1891). The revival of the Distributist Movement is a case in point.

The drive for totalitarian solutions has always exercised a strong appeal among certain groups with a progressivist agenda. The Code of Camaldoli is, therefore, not inspired by the Gospel but by the antithesis of the Gospel – the lust for power not only to rule the kingdoms of this world but to shape them in the image of their own political opinions and prejudices. Unfortunately, this mentality is deeply rooted in the Church and reflects trends that have been accelerating for decades in the ranks of Catholic Action since the publication of Rerum Novarum (1891). The revival of the Distributist Movement is a case in point.

Even Pope Benedict XVI was drawn, wittingly or unwittingly, into the orbit of the Camaldoli Code. With reference to the monastery in which the Code was drawn up, the Pope stated that, “those same cloisters were the setting for the birth of the famous Code of Camaldoli, one of the most significant sources of the Constitution of the Italian Republic.” (11) It was also the basis for the Christian Democrat Party.

This statement shows the survival of the heirs to the old doctrinaire anti-capitalist consensus that framed Italy’s 1948 Constitution, particularly in its sections on social and economic relationship. But did the Pope know that Palmiro Togliatti, the Secretary of the Communist Party of Italy, had participated together with La Pira in the assembly that framed the Constitution of the Republic of Italy in 1948? If so, he certainly showed no apprehension that Socialism would be the natural consequence, the entirely predictable result, if the Code of Camaldoli were ever taken to its logical conclusion of concentration of all political power in the State.

In the next installment, we will be looking at ways in which La Pira harnessed the Camaldoli Code and drove it like a coach and four through the municipality of Florence during his various tenures as Mayor.

Continued

Posted May 20, 2013

The agenda for Montini’s program had already been set by his close friend and collaborator, Jacques Maritain, whose vision of a democracy based on Integral Humanism Montini adopted wholeheartedly. It was a philosophy that preached respect for secular values and religious pluralism. Its aim was to create a new Christian civilization of universal fraternity in which the laity, freed from ecclesiastical authority (but not, alas, total State control) would work with the help of all who shared “human values” to achieve the “common good.” La Pira drank deeply from this poisoned well which became the source of his whole outlook, as expressed in the many Conferences he later organized to find “the ground of a common, Christian and human civilization.”

The dark art of deception

It is noteworthy that Montini was using his spiritual authority decades before Vatican II to preach this naturalistic world-view to his disciples, deceiving them into thinking that his revolutionary “new civilization of love” was a moral obligation drawn from the Gospels. In so doing, he stood condemned by Pope St. Pius X who had censured in Notre Charge Apostolique those who identified the Gospel with the Revolution. Montini’s student movement was evidently one of those “dark workshops” mentioned by Pius X “in which are elaborated these mischievous doctrines which ought not to seduce clear-thinking minds.”

Mischief and deceit were certainly elaborated in the secret meetings that La Pira attended at the Monastery of Camaldoli (2) just outside Florence in July 1943. It was none other than Mgr. Montini who had inaugurated these study weeks in Camaldoli for his FUCI graduates. (3) Among the participants were some prominent figures who had also been formed in the Montinian mould. These included:

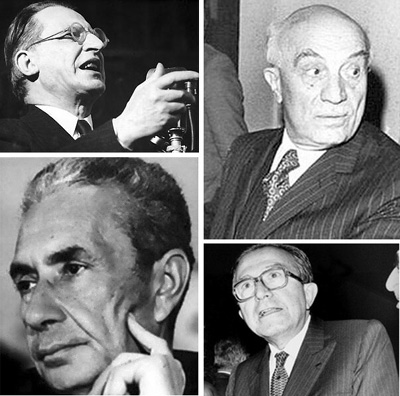

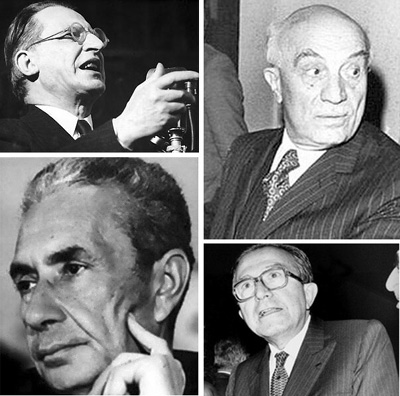

Four Italian Prime Ministers came from the secret group of Montini's disciples - top left, De Gasperi; right, Fanfani; bottom left, Moro; right, Andreotti

- Four future Italian Premiers: Alcide de Gasperi, Amintore Fanfani, Aldo Moro and Giulio Andreotti who made alliances with Communists and Socialists;

- Three economists: Sergio Paronetto, Ezio Vanoni and Paolo Emilio Taviani who favoured a State-planned economy and were later appointed as Cabinet Ministers;

- Pasquale Saraceno, Guido Gonella, Mario Ferrari Aggradi, Enrico Mattei and Giorgio La Pira who occupied leading positions in government or corporations and wanted the State to control the economy and labor;

- Pope Paul VI’s brother, Ludovico Montini, who was elected a Senator.

The Code of Camaldoli

With views such as these, it is only to be expected that the plan they masterminded in their cloistered seclusion at Camaldoli aimed to produce a new society based on a coercive system of social control operated by a bureaucratic elite. To this end, they framed the Code of Camaldoli, a document originally named Per la Comunità Cristiana (For the Christian Community), consisting of 99 propositions to change the political, economic and social order in Italy. They claimed that the Code was a “third way” between Capitalism and Communism, that it was based on the social teaching of the Church, and that it was the embodiment of the Gospels.

But an examination of its contents (4) reveals that it had more in common with the spirit of the Manifesto of Equals of Gracchus Babeuf, as its carefully crafted language masked the latter’s cruder calls for “real equality” and an end to social privilege, particularly in relation to private property.

In the ideal “Christian” society sought by La Pira and his confederates, the following stipulations were considered to be in conformity with the Gospels:

The Monastery of Camaldoli where the meetings of Montini's disciples took place to plan a Socialist Italy

Article 71 took “class war” as its point of departure. It affirmed that the ruling principle of economic life was no longer the rights of the individual but “la giustizia sociale” (“social justice”) which was to be achieved by an equal distribution of goods. (6)

Article 76 specifically undermined private ownership of the means of production;(7) if the owner was considered not to conform to the framers’ idea of the “common good,” i.e., if he has used his property to enrich himself, he could have his right to ownership curtailed.

Article 80 recommended State intervention to limit the consumption and use of goods and the accumulation of wealth. (8)

Article 86 aimed at the elimination of “excessive” economic disparities between citizens and at the transmission/distribution of goods among everyone. It accused the minority of rich people of exercising a despotic power over the economy. (9)

Article 88 attempted to justify State intervention in the economy on the mistaken grounds that the State, rather than private owners, can be trusted to produce fairer outcomes (utilità maggiore): wealth should not be left in the hands of individuals (nelle mani dei singoli).

Article 91 was the equivalent of Marx’s dictum “From each according to his ability, to each according to his need.”

Article 93 envisaged the imposition of taxes to soak the rich as the principal means of the redistribution of wealth (10)

There was even a clause to legitimize civil disobedience in matters that conflicted with the Code, and another to encourage the practice of working mothers.

An antithesis of the Gospel

Far from being the embodiment of the Gospels, what all this reflects is a bundle of old prejudices originating in the mindset that produced the French Revolution and was later popularized by Karl Marx. The Code represents a pattern of thinking that emanates from a visceral hostility to private capital and investment and that regards government means of economic organization as superior to free enterprise. If enacted in legislation, it would mean forcibly overriding the voluntary decisions of consumers and savers, violating their property rights and their freedom of association in order to realize the national government’s economic ambitions.

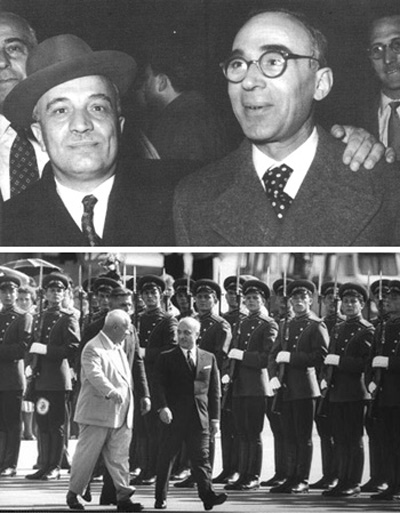

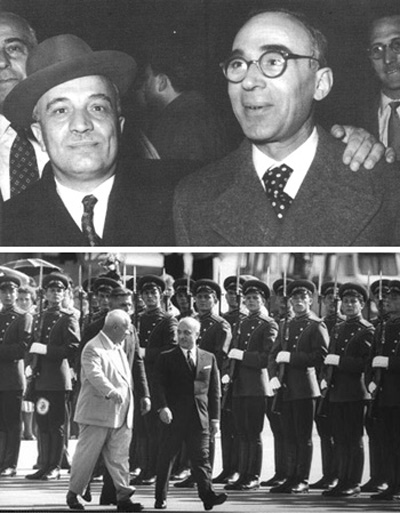

Above, Fanfani embraces La Pira, Florence 1958;

Below, Kruschev welcomes Fanfani, Moscow 1961

Even Pope Benedict XVI was drawn, wittingly or unwittingly, into the orbit of the Camaldoli Code. With reference to the monastery in which the Code was drawn up, the Pope stated that, “those same cloisters were the setting for the birth of the famous Code of Camaldoli, one of the most significant sources of the Constitution of the Italian Republic.” (11) It was also the basis for the Christian Democrat Party.

This statement shows the survival of the heirs to the old doctrinaire anti-capitalist consensus that framed Italy’s 1948 Constitution, particularly in its sections on social and economic relationship. But did the Pope know that Palmiro Togliatti, the Secretary of the Communist Party of Italy, had participated together with La Pira in the assembly that framed the Constitution of the Republic of Italy in 1948? If so, he certainly showed no apprehension that Socialism would be the natural consequence, the entirely predictable result, if the Code of Camaldoli were ever taken to its logical conclusion of concentration of all political power in the State.

In the next installment, we will be looking at ways in which La Pira harnessed the Camaldoli Code and drove it like a coach and four through the municipality of Florence during his various tenures as Mayor.

Continued

- Many members of FUCI (Federazione Universitaria Cattolica Italiana) became statesmen and/or leaders of the Democratic Party;

- The Monastery was founded in the 11th century by St. Romuald, a Benedictine monk. It is now a centre for ecumenical and interfaith dialogue;

- Mgr John Clancy, Apostle for our Time: Pope Paul VI, Collins, 1964, p. 43 (Also Avon, 1963, Ulan Press, 2012);

- See Nico Perrone, Il dissesto programmato: Le partecipazioni statali nel sistema di consenso democristiano, Dedalo, 1991, pp. 14-20;

- The rights of individuals and families are supposedly guaranteed but only “in modo che siano eliminate le situazioni di privilegio derivanti da differenze di classe, di ricchezza, di educazione” [in a way that elliminates privileged situations deriving from class, weath and education differences] i.e. they are subjected to the iron rule of egalitariansim;

- “per cui non possa un individuo o una classe escludere altri dalla partecipazione ai beni comuni” [by which an individual or a class cannot exclude any other from his participation in the common good];

- The State can intervene “escludendo che date categorie di beni strumentali possano essere oggetto di proprietà privata” oppure ponendo delle limitazioni a tale diritto” [to exclude that some categories of instrumental goods might be object of private property or to put limits to such a right];

- With regard to the consumption and use of goods (“beni di consumo e di godimento” [goods of consumme or pleasure]), the State can impose restrictions on their possession by individuals: “una limitazione nel loro uso e nel loro accumulo” [a limit to their use and saving];

- “Un buon sistema economico deve evitare l'arricchimento eccessivo che rechi danno a un'equa distribuzione; e in ogni caso deve impedire che attraverso il controllo di pochi su concentramenti di ricchezza, si verifichi lo strapotere di piccoli gruppi sull'economia.” [A good economic system must avoid the excessive wealth which brings harm to a equal distribution; at any rate it must avoid that by means of the control of a few over the concentration of weath an increased power of small groups may happen in economy];

- “una redistribuzione di beni disponibili” [a re-distribution of the disposible goods];

- Homily 10 March 2012 at an ecumenical gathering in the monastery with Rowan Williams, Archbishop of Canterbury -original here.

Posted May 20, 2013

______________________

______________________