Socio-Political Issues

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

La Pira: A Catholic Communist - Part III

What Was La Pira Doing Behind

the Iron Curtain?

“I have come to pray for peace and unity for all people of the world,” Giorgio La Pira announced flamboyantly during his visit to the schismatic Zagorsk Monastery in the outskirts of Moscow in August 1959, adding that peace among all nations was his “only objective.” (1)

The fact that the original report of the visit was written by his journalist friend, Vittorio Citterich, who had already decided that he was a “saint in the Kremlin,”(2) does not inspire much confidence that there was any substance behind La Pira’s rhetoric – or indeed whether there was any truth in it at all.

Why, we may ask, did La Pira need to go to the capital of the USSR to pray for peace and unity? It is true that his trip to Russia was preceded by a visit to Fatima where he prayed that the prophecy of world peace would be fulfilled. But he always omitted any reference to the essential conditions for the fulfilment of that prophecy, namely the consecration of Russia to Our Lady’s Immaculate Heart.

Why, we may ask, did La Pira need to go to the capital of the USSR to pray for peace and unity? It is true that his trip to Russia was preceded by a visit to Fatima where he prayed that the prophecy of world peace would be fulfilled. But he always omitted any reference to the essential conditions for the fulfilment of that prophecy, namely the consecration of Russia to Our Lady’s Immaculate Heart.

Instead, he fantasized about Florence as the centre of a global network of cities to promote peace, with himself, of course, highlighted on the world stage as the instigator of this unique project.

The real reason for his “pilgrimage” to Russia is not difficult to discern. The Zagorsk monastery was the headquarters of the Russian “Orthodox” Church for ecumenical relations with other religions, particularly with Catholicism. Dorothy Day had it on her “must visit” list during her stay in Moscow (Catholic Worker, October-November 1971) but found it was off limits.

La Pira spoke at the Theological Academy which was housed in the monastery. It was a well-known venue for Soviet-sponsored conferences to promote “peace and cooperation among all nations.”

There, he took advantage of the opportunity to advertise Pope John XXIII’s intention to convene the Second Vatican Council. “The Pope is indeed a father who, with the calling of the Ecumenical Council, has opened his arms to all Christians and all peoples of the world,” he said to the Academy Rector. (3)

Then he told Metropolitan Nikolai that he had come as the “Marian bridge of prayer between Fatima and Moscow, the Churches of East and West.” (4)

A bridge too far

Beneath this pious verbiage about bridges lies the false ecumenism denounced by previous Popes which, as subsequent events have shown, resulted in the betrayal of the Gospel and the rejection of traditional Catholicism. It seems that La Pira was more interested in advancing his own brand of politics than preserving the integrity of the Catholic Faith.

We need to keep in mind that the Russian “Orthodox” Church was a bureaucratic organization controlled by the KGB-infiltrated Council for Religious Affairs. It was – as Solzhenitsyn put it bluntly – a Church run by atheists.

We need to keep in mind that the Russian “Orthodox” Church was a bureaucratic organization controlled by the KGB-infiltrated Council for Religious Affairs. It was – as Solzhenitsyn put it bluntly – a Church run by atheists.

It was also a communist front organization operating as a means of Soviet-manipulated Pacifism for political ends: it was used by Stalin and Khrushchev to win the confidence of Catholics in the West and soften their opposition to Communism.

La Pira’s “peace initiative” with Metropolitan Nikolai in 1959 can be regarded as a preamble to the Pact of Metz which ensured that Communism would not be condemned at Vatican II. It is significant that when La Pira spoke to the Soviet leaders in Moscow and urged them to get rid of State atheism, he did not ask them to give up Communism. That is because, like most progressivist Catholics, he believed that Communism, shorn of its atheism, represented not a danger but a great force for the liberation of humanity.

‘The dove that goes boom’ (5)

What realistic chances were there for the success of La Pira’s “peace pilgrimage” to Moscow? In 1950 Metropolitan Nikolai was elected a member of the Permanent Committee of the World Peace Council, which was the major communist international front organization. It had been established by Stalin to promote the foreign policy aims of the Soviet Union by infiltrating and controlling peace organisations in Western countries.

As Chairman of the External Church Relations Department, both Nikolai and his successor, Archbishop Nikodim (who was to sign the Pact of Metz with the Vatican a few years later), were expected to toe the Party line, a role they carried out so successfully that they were highly valued by the KGB as agents of Russian “peace” propaganda.

As Chairman of the External Church Relations Department, both Nikolai and his successor, Archbishop Nikodim (who was to sign the Pact of Metz with the Vatican a few years later), were expected to toe the Party line, a role they carried out so successfully that they were highly valued by the KGB as agents of Russian “peace” propaganda.

But the call for peace and nuclear disarmament was simply a device calculated to deceive those who were unversed in the subtleties of communist propaganda, for the aim was always to disarm the USA and neutralize the nations of Western Europe while increasing Soviet military capability.

It was not just in military matters that the Russian Schismatic Church used Soviet “peace” propaganda to undermine the will to resist the advance of Communism. The same applied to the ecumenical contacts between the Russian Schismatics and the Vatican.

La Pira’s 1959 “peace pilgrimage” to Moscow was based on irrational assumptions of Soviet good will. But it coincided with the start of the wave of persecution against Catholics in the USSR under Khrushchev. During this time, Nikolai and his successor, Nikodim, managed to convince Western opinion (with Vatican collaboration) of the “friendly” face of Communism towards Catholicism.

In 1973, La Pira made another “pilgrimage” to Zagorsk, this time to meet Patriarch Pimen and Archbishop Nikodim for dialogue about “peace and unity.” The message from the Russian religious leaders was that “Christians should try to understand the positive aspects of the trend towards Socialism evident in many places.” (6) But for La Pira and the Russian Schismatics, “peace and unity” had a particular meaning – the removal of all obstacles in the way of Communism being accepted in the Catholic Church. The Pact of Metz lives on.

The calculus of risk ignored by Catholic communists

We can see from these examples of ecumenism in action how the “peace pilgrimages” changed the whole calculus of risk according to which the representatives of the Catholic Church had always approached contacts with potential enemies of the Faith. The result was that the Church and society were left open to infiltration by false religions and Communism.

Little wonder, then, that even communists voted La Pira into office as Mayor of Florence and President Gorbachev eulogized him for his efforts to “knock down walls and build bridges.” (7)

Continued

Posted April 12, 2013

The fact that the original report of the visit was written by his journalist friend, Vittorio Citterich, who had already decided that he was a “saint in the Kremlin,”(2) does not inspire much confidence that there was any substance behind La Pira’s rhetoric – or indeed whether there was any truth in it at all.

Giorgio la Pira peace initiative - a preamble to the Pact of Metz

Instead, he fantasized about Florence as the centre of a global network of cities to promote peace, with himself, of course, highlighted on the world stage as the instigator of this unique project.

The real reason for his “pilgrimage” to Russia is not difficult to discern. The Zagorsk monastery was the headquarters of the Russian “Orthodox” Church for ecumenical relations with other religions, particularly with Catholicism. Dorothy Day had it on her “must visit” list during her stay in Moscow (Catholic Worker, October-November 1971) but found it was off limits.

La Pira spoke at the Theological Academy which was housed in the monastery. It was a well-known venue for Soviet-sponsored conferences to promote “peace and cooperation among all nations.”

There, he took advantage of the opportunity to advertise Pope John XXIII’s intention to convene the Second Vatican Council. “The Pope is indeed a father who, with the calling of the Ecumenical Council, has opened his arms to all Christians and all peoples of the world,” he said to the Academy Rector. (3)

Then he told Metropolitan Nikolai that he had come as the “Marian bridge of prayer between Fatima and Moscow, the Churches of East and West.” (4)

A bridge too far

Beneath this pious verbiage about bridges lies the false ecumenism denounced by previous Popes which, as subsequent events have shown, resulted in the betrayal of the Gospel and the rejection of traditional Catholicism. It seems that La Pira was more interested in advancing his own brand of politics than preserving the integrity of the Catholic Faith.

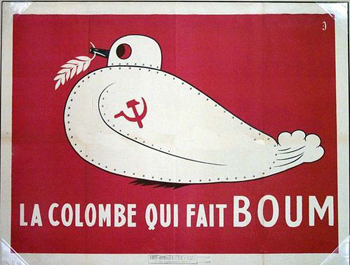

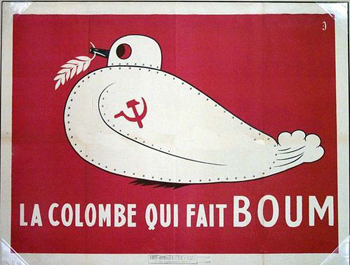

To fool the West Communism promoted peace, symbolized by a dove by fellow communist Picasso

It was also a communist front organization operating as a means of Soviet-manipulated Pacifism for political ends: it was used by Stalin and Khrushchev to win the confidence of Catholics in the West and soften their opposition to Communism.

La Pira’s “peace initiative” with Metropolitan Nikolai in 1959 can be regarded as a preamble to the Pact of Metz which ensured that Communism would not be condemned at Vatican II. It is significant that when La Pira spoke to the Soviet leaders in Moscow and urged them to get rid of State atheism, he did not ask them to give up Communism. That is because, like most progressivist Catholics, he believed that Communism, shorn of its atheism, represented not a danger but a great force for the liberation of humanity.

‘The dove that goes boom’ (5)

What realistic chances were there for the success of La Pira’s “peace pilgrimage” to Moscow? In 1950 Metropolitan Nikolai was elected a member of the Permanent Committee of the World Peace Council, which was the major communist international front organization. It had been established by Stalin to promote the foreign policy aims of the Soviet Union by infiltrating and controlling peace organisations in Western countries.

Above, a dove shaped as a tank ridicules the communist pretense of peace

But the call for peace and nuclear disarmament was simply a device calculated to deceive those who were unversed in the subtleties of communist propaganda, for the aim was always to disarm the USA and neutralize the nations of Western Europe while increasing Soviet military capability.

It was not just in military matters that the Russian Schismatic Church used Soviet “peace” propaganda to undermine the will to resist the advance of Communism. The same applied to the ecumenical contacts between the Russian Schismatics and the Vatican.

La Pira’s 1959 “peace pilgrimage” to Moscow was based on irrational assumptions of Soviet good will. But it coincided with the start of the wave of persecution against Catholics in the USSR under Khrushchev. During this time, Nikolai and his successor, Nikodim, managed to convince Western opinion (with Vatican collaboration) of the “friendly” face of Communism towards Catholicism.

In 1973, La Pira made another “pilgrimage” to Zagorsk, this time to meet Patriarch Pimen and Archbishop Nikodim for dialogue about “peace and unity.” The message from the Russian religious leaders was that “Christians should try to understand the positive aspects of the trend towards Socialism evident in many places.” (6) But for La Pira and the Russian Schismatics, “peace and unity” had a particular meaning – the removal of all obstacles in the way of Communism being accepted in the Catholic Church. The Pact of Metz lives on.

The calculus of risk ignored by Catholic communists

We can see from these examples of ecumenism in action how the “peace pilgrimages” changed the whole calculus of risk according to which the representatives of the Catholic Church had always approached contacts with potential enemies of the Faith. The result was that the Church and society were left open to infiltration by false religions and Communism.

Little wonder, then, that even communists voted La Pira into office as Mayor of Florence and President Gorbachev eulogized him for his efforts to “knock down walls and build bridges.” (7)

Continued

- Catholic Herald, 28th August 1959

- Citterich accompanied La Pira to Moscow and wrote a report of the visit in the Florentine Christian Democrat daily, Giornale del Mattino. He wrote several articles about La Pira and published a book entitled Un Santo al Cremlino: Giorgio La Pira, Edizioni Paoline in Torino, 1986. If La Pira was considered a living saint before he died, it was largely due to the hyperbolic reports of Vittorio Citterich.

- Ibid., Catholic Herald, August 28, 1959

- See here.

- This was a 1951 anti-communist cartoon designed as a satire of Pablo Picasso’s “Dove of Peace” which was the symbol of the international communist “peace” movement. The cartoon depicted a dove in the form of a Soviet tank to expose the real motives behind Stalin’s “peace” propaganda.

- Catholic Herald, 6 July 1973. This information was first published in the Osservatore Romano, 16 June 1973. Quoted in Jonathon Luxmoore and Jolanta Babiuch, The Vatican and the Red Flag, Geoffrey Chapman, 1998, p. 164.

- Gorbachev received the Giorgio La Pira Award for Culture and Peace in November 1999.

Posted April 12, 2013

______________________

______________________