|

Stories & Legends

The Superb Memory of

St. Thomas Aquinas

Hugh O'Reilly

Recently I started to read The Book of Memory by Mary Carruthers, (1) a classic study of memory in medieval culture. In the Introduction, she pays homage to the brilliant intellect and exceptionally trained memory of St. Thomas Aquinas.

This description of the Philosopher par excellence is from testimonies given at the first canonization inquiry compiled by Thomas of Celano, who also knew Friar Reginald, the secretary/assistant of St. Thomas:

St. Thomas greatly relied on his memory |

“Of the subtlety and brilliance of his intellect and soundness of his judgment, sufficient proof is his vast literary output, his many original discoveries, his deep understanding of the Scriptures. His memory was extremely rich and retentive: Whatever he had once read and grasped, he never forgot. It was as if knowledge were ever increasing in his soul as page is added to page in the writing of a book.

“Consider, for example, that admirable compilation of Patristic texts on the four Gospels which he made for Pope Urban [the Catena Aurea or Golden Chain], and which, for the most part, he seems to have put together from texts that he had read and committed to memory from time to time while staying in various religious houses.

“There is also the testimony of Friar Reginald, his socius, and of his pupils and of those who wrote to his dictation, who all declare that he used to dictate in his cell to three secretaries, and even occasionally to four, on different subjects at the same time. …

“No one could dictate simultaneously so many materials without a special grace. Nor did he seem to be searching for things as yet unknown to him; he seemed simply to let his memory pour out its treasures. …

“He never set himself to study or argue a point, or lecture or write or dictate without first having recourse inwardly to prayer for the understanding and the words required by the subject. When perplexed by a difficulty, he would kneel and pray. Then, on returning to his writing or dictation, he was accustomed to find that his thought had become so clear that it seemed to show him inwardly, as in a book, the words he needed.

He dictated to three scribes on different topics at one time |

“Even at meal times his recollection continued; dishes would be placed before him and taken away without his noticing. And when the brethren tried to get him into the garden for recreation, he would draw back swiftly and retire to his cell alone with his thoughts.” (2)

Because of the full accounts we have from the hearings held for his canonization as well as several surviving autograph drafts of some of his early works, we know a good deal about the actual procedures that St. Thomas followed in composing his works. A paleographic study conducted by Antoine Dondaine, a specialist in the field, confirmed that, indeed, St. Thomas truly did dictate to three or four secretaries. (3)

For example, the drafts we have show that St. Thomas wrote the Summa contra gentiles first in a lettera inintelligibilis, that is a shorthand of his own making, and then summoned a secretary to take down the text in a legible hand as St. Thomas read his own autograph aloud. When one scribe tired, another took his place.

At the table of St. Louis

We mentioned that St. Thomas made a compilation of patristic comments on the Gospels, the Catena aurea, around 1263. As Bernardo Gui notes, he put together those commentaries based on texts that he had read and committed to memory.

Another confirmation of the way he worked is the well-known incident of St. Thomas at dinner with King St. Louis IX, which took place around 1269-1270 when St. Thomas was working on the Part II of the Summa theologica.

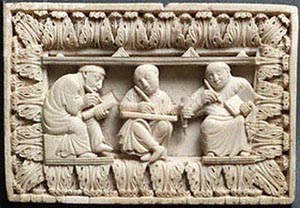

A university classroon in the Middle Ages |

St. Thomas at times would dine at the table of the King seated next to him. On one of these occasions, the Saint was extremely preoccupied by the argument he was developing against the Manicheans. As the dinner progressed, he suddenly struck the table, saying in a loud voice, “Ergo concluso contra Manichaeos” (“With this I finish with the Manichaens!”)

Then he called out to Friar Reginald, his secretary who had accompanied him, as though he were still at study in his cell: “Friar Reginald, get up and write!” Friar Reginald proceeded to commit to paper the thoughts of Friar Thomas.

This is not to say that St. Thomas never made reference to manuscripts, for it is known that he did. What is clear, however, is that he did not look up each quotation in a manuscript tome as he composed. The texts were filed in his memory, in an ordered form. Once there, they stayed there for use on other occasions.

It is a testimony to the great memory of the man, and to the mnemonic techniques of the time. The nature of those techniques and how they were taught is the subject of much of Carruthers’ book. Memoria meant, at that time, trained memory, educated and disciplined according to a well-developed pedagogy. In my opinion, it would be good for modern educators, so proud of the progress made in technology, to consider the regression we have suffered by disregarding the training of our memories.

Supernatural assistance

We should not suppose that St. Thomas relied just on a well-trained memory to compose his works. As Bernardo Gui pointed out, St. Thomas never studied without first having recourse to prayer, he also relied strongly on supernatural help for clarity and inspiration.

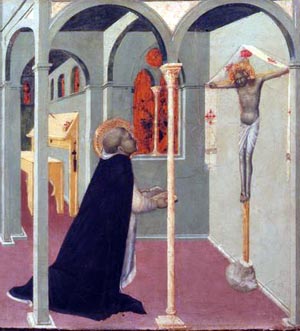

When facing a difficult question St. Thomas had recourse to prayer |

An example of the kind of supernatural assistance the Saint received is found in this interesting incident.

When he was writing his commentary on Isaiah, St. Thomas had been engrossed and troubled for days over the interpretation of a particular text. Finally, one night when he had stayed up to pray, Friar Reginald overhead him speaking with other persons in the room although he could not make out the words or recognize the other voices.

Then all fell silent, and he heard his master’s voice calling, “Friar Reginald, get up and bring a light and the commentary on Isaiah. I want you to write for me.”

So Friar Reginald rose and began to take down the dictation, which ran so clearly, he later testified, that is was as if the master was reading aloud from a book under his eyes.

Pressed by Friar Reginald for the names of his mysterious companions, St. Thomas finally replied that St. Peter and St. Paul had been sent to him, “and told me all I needed to know.” (4)

With these stories we can glimpse the culture of the Middle Ages, which relied so strongly on memory and was rooted so deeply in the supernatural.

1. M. Carruthers, The Book of Memory, A Study of Memory in Medieval Culture, Cambridge Univ. Press, 1990, Introduction.

2.“The Life of St. Thomas Aquinas,” by Bernardo Gui and Bartholomew of Capua, “Testimony at the First Canonization Inquiry,” trans. by K. Foster, Bibliographical Documents for the Life of St. Thomas Aquinas, Oxford: Blackfriars, 1949, pp. 50-51, 37, 107, in ibid., p. 3.

3. Ibid., p. 4.

4. Foster, Biographical Documents, p. 38, Gui, p. 16, Tocco, p. 31, in ibid, p. 5.

Posted April 11, 2012

Related Topics of Interest

St. Thomas Aquinas St. Thomas Aquinas

Two Aspects of the Medieval Mentality Two Aspects of the Medieval Mentality

The Moral Education of the Future Knight The Moral Education of the Future Knight

The Crisis in Catholic Education and St. Thomas’ Solution The Crisis in Catholic Education and St. Thomas’ Solution

Are Students Less Educated Today than 50 Years Ago? Are Students Less Educated Today than 50 Years Ago?

St. Thomas against the Socialist Distribution of Property St. Thomas against the Socialist Distribution of Property

Related Works of Interest

| |

|

Legends | Religious |

Home | Books | CDs | Search | Contact Us | Donate

© 2002-

Tradition in Action, Inc. All Rights Reserved

|

|

|