1. Introduction

The veil has been a topic of increasing interest in the last few years, largely because of the recent fascination with Islam. Particularly regarding the recent law in France forbidding the display of any religious symbol in public schools, many have asked what the religious significance of the veil is. Is it simply a social custom, or is it actually required by the Islamic religion? Is a simple covering on the head sufficient, or does the law require the full-headed burkhas of Afghanistan? These questions have been of some mild interest of late, and always in reference to Islam.

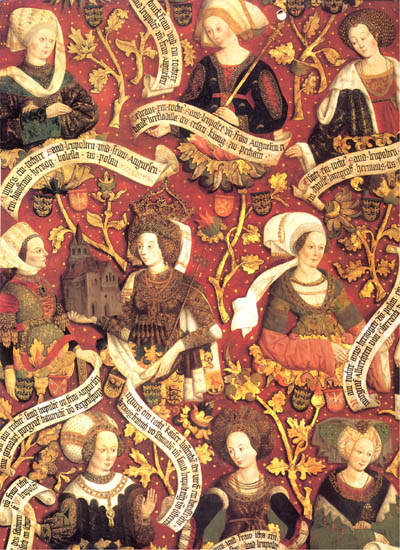

Ladies in an Austrian family tree picture (1490) wear various kinds of veils and headcoverings |

But is there a Catholic tradition of veils, and if so, what does it entail? Clearly it has been out of practice for a long time, if it ever did exist. What is the tradition? What does it require? Does it bind under any penalty? These questions and many others are what this essay intends to answer. For it is clear that there is a Catholic tradition of the veil; it persisted even until the 1960s, in the form of the custom of women wearing head coverings in churches, and even exists to this day in many Eastern-rite Catholic communities.

This article will examine the tradition of the veil from apostolic times through the present day, with particular emphasis on the teachings of Fathers and the great Angelic Doctor, St. Thomas Aquinas. It shall further examine the ramifications of this tradition on the present day, and discuss the arguments on whether this tradition ought to be revived, in whatever form, or allowed to lie where it has fallen. My methodology, however, demands a certain degree of explanation; before I begin, then, I shall explain how I set out to do what I have done.

First, I did not want my discussion to be limited by the opinions of modern translators who have brought the works of great Catholic scholars to the English readers of today. While I have no doubt that most translators approach their task firmly intending to convey the works of their subject with the greatest possible degree of accuracy, it is impossible for a translation to accurately reflect the passage in the original tongue. Indisputably, they may come very close, particularly when the languages are closely related to one another, such as English and French; with two languages like Latin and English, however, there cannot but be some missing meaning in the original that has not found its way into the translation, as well as some additional meaning in the translation which cannot be found in the original. No comment upon translators is intended by this observation; I only mean to set up my methodology for dealing with foreign-language texts.

For this reason, I have elected to do as much of my own translating as possible. Some of these works have never been translated, and so I have been assisted in my determination by a lack of any possible alternatives. The bulk of St. Thomas and St. Augustine, however, have been translated, and I have therefore ignored many excellent translations in the production of this essay. However, in doing so I have had recourse to the original, which should assuage the reader’s conscience when he considers the neglect which these superlative translators are now receiving. I have also translated certain Scriptural passages from the original Greek, where it seemed relevant; however, I have not attempted to translate the works of the Greek Father St. John Chrysostom anew, and have instead used a pre-existing translation. Partly, my insufficient knowledge of Greek is to blame; partly, the difficulty of finding St. John in Greek is at fault. Either way, however, I hope that the reader will forgive me, and if the translation is such that St. John’s own words would render my analysis of his text merit less, I hope that the rest of my work will stand on its own.

Furthermore, because I lack an established reputation as a translator, I elected to supply the reader with the original text wherever my translation has come into play. While this does somewhat encumber the documentation, it acts as my gesture of good faith by supplying the original of each translated passage. For those who cannot read it, it is at least a statement of confidence that I will not be exposed to ridicule by those who can; and for those who can, the original provides far more expressive power than anything my translation can convey and will greatly enrich my discussion of this topic. I hope that this decision will prove a burden to no one, and a boon at least to some.

In the next installment, I will begin my discussion. My examination of the Catholic veil tradition shall be centered upon the only infallible text concerning the veil ever promulgated throughout History, and shall build from there. And so I embark upon my quest, and I pray for the blessing of Almighty God upon my project and upon the reader, whom may Our Lord and Savior shower with blessings and open to the knowledge of the truth.

Posted March 31, 2005

Go to Part 1 Part 2 Part 3 Part 4 Part 5 Part 6 Conclusion

The pleasure TIA has to publish collaborations of our guest columnists does not imply that it endorses all the opinions expressed in their articles.

Return to TOP

Related Topics of Interest

Restoration: Let's Begin with the Veil Restoration: Let's Begin with the Veil

St. Pius X on Priestly Dignity and Propriety St. Pius X on Priestly Dignity and Propriety

Titles and Signs of Respect for Priests and Religious Titles and Signs of Respect for Priests and Religious

|