|

Catholic Customs

Pictorial Commentary on Pius X's Counsel to Priests

Pius X on Priestly Propriety and Dignity

Marian T. Horvat, Ph.D.

These were words of advice of Pope St. Pius X to Priests on the need for priestly dignity and propriety at the beginning of the last century:

“In order never to be guilty of any unedifying act, the priest must regulate his actions, his movements and his habits in harmony with the sublimity of his vocation. He who on the altar almost ceases to be mortal and takes on a divine form, remains always the same, even when he comes down from the holy hill and leaves the temple of the Lord. Wherever he is, wherever he goes, he never ceases to be a priest, and the serious reasons that compel him always to be grave and appropriate accompany him with his dignity everywhere.

“Hence he must have that gravity that will ensure that his words, his bearing, and his way of working arouse love, win authority and excite reverence. For, the very reasons that oblige him to be holy make it a duty for him to show it by his outward acts in order to edify all those with whom he is obliged to come into contact. A composed and dignified exterior is a powerful eloquence which wins souls in a much more efficacious manner than persuasive sermons. Nothing inspires greater confidence than an ecclesiastic who, never forgetting the dignity of his state, demonstrates in every situation that gravity which attracts and wins universal homage.

“If, on the contrary, he forgets the holiness of the sacred character which he bears indelibly impressed and engraved on his soul, and if he fails to show in his outward conduct a gravity superior to that of certain men of the world, then he causes his ministry and religion itself to be despised. For when gravity is wanting in its leaders, the people lose respect and veneration for them.” (1)

These comments of Pius X to priests reflect the customary teaching of the Church since the time of St. Peter until Vatican II. Rather than analyze this farsighted warning, let us apply the Pontiff’s words to the pictures we have before us in this article.

Informations Catholique Internationales, December 1, 1968 |

In this first picture, at left, the year is 1968, shortly after the close of Vatican II when the first deleterious effects of the secularization of the clergy were becoming apparent. Two French priests and a nun are at a bar demonstrating their “adaptation to the modern world.” The man at the far left in the photo, with whom Father X is engaging in a conversation, seems to be displaying surprise and mistrust at being approached by a priest in these circumstances. His suspicion is one of a person who might be saying, “What are you religious doing here? This is a place for me, not for priests and nuns.”

It should come as no surprise should he be censuring the attitude of the clergyman The scene recalls to us the words of Pius X that if a priest forgets the holiness of his sacred characters and fails to show in his outward conduct a gravity superior to that of men in the world, “then he causes his ministry and religion itself to be despised.”

On the contrary, at right, you can observe a young cleric, upright, serious, dressed with dignity, sitting erect with noble bearing, assurance and dignity in a stately chair. The position of the hands, closed with serenity but firmness, express the energy that a good priest should have to direct souls and combat errors. The face, also reflecting an air of serenity, is a face of a man who does not fear anything. The eyes reflect a man accustomed to facing the sad reality of this valley of tears and an extreme confidence in a strength much superior to his, which is the strength of the grace of God.

You are looking at Giuseppe Sarto, eldest of the eight children of a village postman and his seamstress wife, as an assistant priest of Tombolo, Italy.

The Leaven, August 23, 2002 |

Now I would ask you to direct your eyes to the picture at left, taken from the Kansas diocesan newspaper, and you will see Archbishop James Keheler trying to appear modern, joining in the “song of praise” and imitating the dance of some youth at the last World Youth Day.

The dance gestures of the Prelate seem so awkward and ridiculous that even though he is trying his best to be one of the young people, it is clear he does not fit in this role. Instead of drawing sympathy, as certainly he intended to do, his accommodation to the modern revolutionary dance makes him a target for ridicule and causes sadness in the viewer, who asks himself: “Why is a prince of the Church acting like this?”

It is a progressivist myth that insists the priest generates adhesion to the “good news of the Gospel” by making himself like today’s modern youth. Pope Pius X gives words of perennial wisdom on how the priest will earn true respect and veneration:

“If the faithless modern world has stripped the priest of that halo of veneration that he formerly was crowned with, it is more than necessary that in our times he should by his bearing win once again the people’s respect for his high dignity and propriety. The more so because experience teaches us that the world … is shocked not only by the slightest failings it discerns in ecclesiastics, but even by their most innocent actions whenever these do not bear the seal of that gravity which it has a right to expect of them …

“Thus we recommend to you priestly gravity … With St. Ambrose I say to you: “Nihil in sacerdote commune cum multitudine.” (2) [Let nothing in the priest be like the common crowds.]

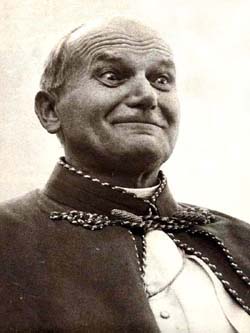

At right, you can observe a man with a different mentality. Always aware of his mission of being a Prince of the Church, he wears his full episcopal cassock, worn as a symbol of his dignity. Around his waist is the beautiful silk cincture, which symbolizes continence. On his head he wears the zucchetto, which indicates his status as Bishop. Befitting of the importance of his role, he also wears a majestic cloak, a sign that as a shepherd he covers his sheep from the dangers of the world and exposure to evil.

In his hand he holds his Bishop’s cap. A beautiful gold chain elegantly bears his pectoral cross, a reliquary for the True Cross, which reminds him to keep the Cross close to his breast. In synthesis, the entire man is a symbol of his elevated mission.

In the posture of his arms, one discerns a great calm and security. In the face, a profound honesty and seriousness before God and before himself, as well as a full vision of the evil that surrounds him and the Holy Church. His physiognomy expresses sadness for that evil and, at the same time, a determination to dedicate his life to combat it. It is a kind face, but with none of the soft sentimentality of the weak.

Once again, you are looking at Giuseppe Sarto, as Bishop of Mantua, who provides a living example of his wise counsels on priestly dignity and propriety.

Epoca, January 27, 1979 |

Let us return to the left column. The picture at left shows a man in a cassock making a humorous gesture to make people laugh – he is crossing his eyes, like a boy would do to divert and amuse his friends. He enjoys the laughter raised by his antic, by the surprise of onlookers at seeing the Vicar of Christ playing the clown.

It is John Paul II at a moment of relaxation entertaining the photographers in 1979.

It would be impossible to imagine such a clowning gesture from Pope Pius X at right below, even if he were not vested in the full majesty of papal pomp. Behind him one can see the pontifical throne. He wears the triple crown, and on his finger is the Fisherman’s Ring bearing a beautiful emerald. Over his shoulders, the solemn papal mantle is draped. All this radiates the splendor and dignity of the Papacy that existed in Holy Church before Vatican II began to relegate these symbols to the closets and museums.

The Pope, in a position of blessing, gazes at us as if to say these few words: “My mission is accomplished. I have fought the good fight.”

Everything that was in potential in the man in the first two photos is realized here in its plenitude. He is acting before God and before man with his only concern that of defending and glorifying the Catholic Church. He had smashed the enemy, Modernism; he had taken all the measures possible in his short pontificate to favor the good and thwart the evil. Quietly, with unshaken calm, he denounced and condemned evil wherever he saw it.

In his face in this photo is the same courage, the same determination, the same seriousness as in the others. But there is also more sadness, more peace, and complete solitude, the solitude of a saint in a revolutionary epoch. One can catch a glimpse of the meaning of the words he spoke, “De gentibus non est vir mecum.” [Among all the peoples, there is not one man with me.]

What was he seeing in that sad and profound gaze? Was he perhaps glimpsing something of the crisis that would rock the Catholic Church with the Council and its consequences? Who knows?

Certainly his urgent words to priests take on special significance today, worth pondering and remembering: “Great is the priestly dignity, but great also is his ruin if he is not faithful to his duties, because unfortunately it is true that the corruption of the very good is a frightful thing. Optimorum corruption, teterrimum.”

1. Recipe for Holiness: St. Pius X and the Priest, (Lumen Christi Press, Houston: 1970), “Dignity and Propriety,” pp. 81-2.

2. VI. Epistle ad Irenaeum, in ibid., pp. 82-3.

Posted August 8, 2003

|

Customs | Manners | Cultural | Home | Books | CDs | Search | Contact Us | Donate

© 2002- Tradition in Action, Inc. All Rights Reserved

|

|

|