|

The Saint of the Day

Blessed Charles the Good – March 2

Prof. Plinio Corrêa de Oliveira

Biographical selection:

Charles (1083-1127) was the son of St. Canute (or Knud), King of Denmark. His father was murdered when Charles was age five, and his mother Adele took him to the court of her father, the Count of Flanders, in Bruges. Charles became a knight and accompanied his uncle on the Second Crusade to recover the Holy Land from the Moors. Upon his return, he received the County of Flanders from his cousin Baldwin.

Count Charles had a profound love for justice. Every day after dinner, he would meet with three theologians who would explain two or three chapters of Scriptures, lessons to which he listened with great pleasure. He loved God’s Name so much that he forbade any of his subjects to blaspheme or take the name of God in vain. The punishment for blaspheming was to lose a hand or foot. His love for justice made him the terror of evildoers who oppressed the poor, exploited widows, and persecuted orphans.

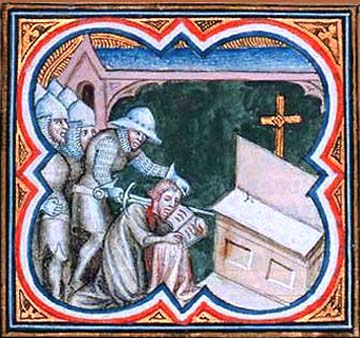

Charles the Good was murdered as he prayed before an altar of Our Lady

|

He acquired such a great reputation for justice and goodness that when the Imperial throne became vacant, it was offered to him. He refused it, as he had refused before to be the King of Jerusalem. He declined the honor because he needed time to take care of his people in Flanders.

When he found out that certain high-ranking bourgeois had stockpiled a large amount of grain to sell at exorbitant prices, he obliged them to sell it at once at a fair price. This aroused their fury and the leaders of the profiteers formed a plot to murder the Count.

Blessed Charles used to go to Mass every day in the Church of St. Donatian near his castle. One morning in 1127, Borchard, the nephew of one of the leaders of the plot, attacked and beheaded Charles at the moment when he was kneeling and praying alone before the altar of Our Lady.

Comments of Prof. Plinio:

The first thing one notes in this selection is the hatred that Blessed Charles of Flanders inspired among his enemies because he was a representative of the virtue of justice, especially in the case of the grain related above. He died as a witness of Catholic justice because he strove to install a civil order that followed the precepts of Our Lord.

A point we should consider today is that in the Middle Ages, the title “the good” that follows Charles’ name referred not only to the charitable characteristics of a person, as it would today, but also to his justice, to his zeal in defending the good cause. Today, “the good” would refer to the man who gives alms to the poor. In that time, however, the term had a broader sense that is useful for us to remember.

Also, we should realize that to be a Prince of Denmark at that time was much less than to be a Count of Flanders. The Danish Monarchy was considered a second class monarchy. The people and other Kings did not refer to the Danish King as His Majesty, but as His Highness, which is normally the title given to princes, not monarchs. The Danish Monarch was only recognized as His Majesty in the 18th century by Louis XIV in a censurable initiative; the other Kings then followed his example.

There was a good reason for this exclusion. Denmark was a semi-barbarian kingdom, where the normal ambience was one of unrestrained passions, reckless behavior, and barbarian habits. I say this not to disparage Denmark, but to demonstrate that the family of Blessed Charles had great valor in being faithful to Catholic principles, allowing the faith to govern reason, and the reason to subdue the passions. This description of the life of Charles of Flanders shows how faith completely governed his reason and bad tendencies.

In contrast to the Danish kingdom, the County of Flanders was very civilized, with a high cultural level. It was also quite wealthy. It enjoyed a great political importance in Europe at that time. After his father’s death, Charles went there with his mother Adele, who was from the family of Flanders. From age five onward, he received his formation in the court of Flanders. He became a knight and dedicated his life to the defense of the Church and the Catholic cause, accompanying his uncle on the Crusade. He had, therefore, the glory to fight for the defense of the Holy Land. On his return he inherited the throne of the County of Flanders and embarked on a new course of action, no longer as a warrior but as a governor.

The 12th century Castle of Gravensteen in the Flanders

|

As a ruler he distinguished himself in his admiration for Sacred Scriptures. He was not the kind of man with an obsession for only practical things, living exclusively to govern. He knew how to keep a psychological distance from the absorbing day-to-day matters. After dinner in the evening he would receive the visit of three theologians who were experts in Holy Letters. Charles wanted to know about the things of God. These ecclesiastics would read, comment upon and discuss this or that part of the Scripture with him.

You can imagine the scene. It is night in the Castle of the Count of Flanders: outside a complete silence reigns; only the song of a guard on his rounds can be heard from time to time. Inside, in a great drawing room, the fireplace is lighted. Seated on some large carved chairs are the Count and his three theologians, along with some members of the family who have remained to quietly listen and learn. The religious have one of those large, heavy and beautifully hand-written books of Scriptures, which has been placed on a stand. One of them goes to the stand, reads a passage, and then returns to his place.

Calm and elevated, the commentary and discussion that follows is turned toward understanding the designs of God and Our Lady for mankind and how to put them in practice. On those nights one could say that Heaven embraces earth and prepares those saintly men for their nightly repose and the next day’s work and fight. The life of that castle was noble and beautiful on those evenings, so very different from the cursed and tormented pagan nights of our times.

His zeal to defend the name of God led him to issue a law that punished a man who blasphemed with losing his hand or foot. He was a saint and he knew well what he was doing. With today’s mentality, steeped in liberalism and sentimentalism, many persons think that this is cruel and wrong. But this was not the thinking of Blessed Charles. He considered this measure would do a great good for the guilty ones as well as for public opinion in his County. He was right.

Someone who committed this crime and was punished would bear the mark of his sin and chastisement for his entire life to remind him and society how bad his action was. It was a grace for him to be punished in this life, and not in the next. Today people do not consider the punishments in Purgatory and Hell that we will certainly face unless we make expiation in this life. For this reason, they lack an indispensable reference point to make a fair judgment about what is an appropriate chastisement.

Charles was careful to protect the poor, widows and orphans because the supreme power of a State must watch over those who have nothing. His fame for looking after his people made him so celebrated that he was invited to become Emperor. It was the highest temporal dignity on earth, but he refused, just as he had refused earlier to be King of Jerusalem.

Someone could ask me: But wouldn’t it have been better for the Catholic cause to have a saint as Emperor? So, why didn’t he accept? In principle this is true. But God has a different plan for each one of us. Charles probably received an inspiration that made him know the will of God for him.

Then there is the episode of his brutal death, reflecting the hatred of the sons of darkness for the sons of light. After a life filled with battle, good acts of government, and prayer and meditation, a death abounding with merit came to him. The palm of martyrdom crowned his life while he was praying before the altar of Our Lady.

Let us ask Blessed Charles the Good to make us strong to bear the hatred, persecution, calumnies, tricks, and silence that the enemies of the Church – who have infiltrated into her very bosom – employ against us today. Let us ask him to prepare us, through the intercession of Our Lady, to follow the will of God for each one of us – in battle, work, command, prayer, obedience or even martyrdom.

| | Prof. Plinio Corrêa de Oliveira | |

The Saint of the Day features highlights from the lives of saints based on comments made by the late Prof. Plinio Corrêa de Oliveira. Following the example of St. John Bosco who used to make similar talks for the boys of his College, each evening it was Prof. Plinio’s custom to make a short commentary on the lives of the next day’s saint in a meeting for youth in order to encourage them in the practice of virtue and love for the Catholic Church. TIA thought that its readers could profit from these valuable commentaries.

The texts of both the biographical data and the comments come from personal notes taken by Atila S. Guimarães from 1964 to 1995. Given the fact that the source is a personal notebook, it is possible that at times the biographic notes transcribed here will not rigorously follow the original text read by Prof. Plinio. The commentaries have also been adapted and translated for TIA’s site.

|

Saint of the Day | Home | Books | CDs | Search | Contact Us | Donate

© 2002- Tradition in Action, Inc. All Rights Reserved

|

|

|