|

The Saint of the Day

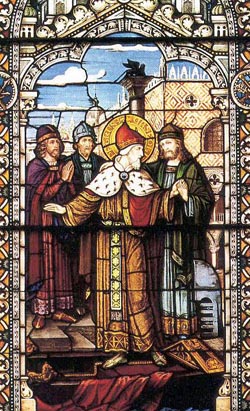

St. Peter Orseolo, January 10

Prof. Plinio Corrêa de Oliveira

Biographical selection:

St. Peter Orseolo, Doge of Venice

|

St. Peter Orseolo, born in 928, had an exciting life. Son of a noble and wealthy family of Venice, at age 20 he commanded the Venetian fleet in a successful effort to conquer the pirates that infested the Adriatic Sea.

He probably played a role in a revolution that led to the murder of Doge Peter Candiano IV in 976. During the overthrow, the Doge’s Palace was burned and part of Venice destroyed. Peter Orseolo then was chosen the next Doge of Venice.

He revealed himself to be an energetic, skillful, and indefatigable administrator. As soon as he accepted the office, he began to rebuild the edifices damaged by the fire. He rebuilt at his own expense the Doge’s Palace and the Church of St. Mark.

He had a passionate and complex personality. On September 1, 978, he left Venice secretly and traveled to Roussillon at the foot of the Pyrenees on the borders of France and Spain, and asked to enter the Abbey of Cuxa as a monk. Even his wife did not know where he was going.

Under the direction of the Abbot Guarinus, he lived a holy life and dedicated himself to prayer and penance until he died in 987. Many miracles were worked at his tomb. His only son became one of the greatest and most celebrated Doges of Venice.

Comments of Prof. Plinio:

The description of the life of St. Peter Orseolo transfers us to a time and place completely different from the one we are accustomed to. You need to imagine the city of Venice in a world different from ours.

The streets of Venice are channels of water. Below, a painting by Caneletto features the Doge's Palace, which was restored by St. Peter Orseolo after it was damaged by fire.

|

Venice is a grandiose and charming city in northern Italy on the shore of the Adriatic Sea. Originally there was just an ensemble of small islands very close to one another. But when the barbarians, especially the Huns, invaded Western Europe, some of the inhabitants of neighboring lands fled to those islands. After the danger passed, they remained and embarked on a lively commerce with the East. They became wealthy and built a unique city atop those numerous islands. Soon, however, they had used up the available land, so they started to build on the sea, on pillars. They found a secure way to do this and the number of houses and palaces multiplied. This is how the marvelous city of Venice was built

on part land and part sea.

You can imagine this Venice with hardly any streets. The streets are the canals that ran between the islands. When the Venetians want to go out, they get into very beautiful, elegant boats called gondolas, and are rowed through the channels, instead of walking or driving. The drivers of these gondolas – the gondolieri – did not use horns to avoid collisions. When they would cross channels where they could not see if other gondalas were coming, instead of honking a horn, they sang out a very harmonic call of warning.

Today the gondolas are black. In the time of St. Peter Orseolo the gondolas were golden with beautiful fabric overhead coverings, pillows for the seats, and rugs for the floor that offered the passengers both comfort and distinction. Traveling at night along those canals, a person would see Venice with its lights reflecting and dancing on the surface of the sea; he would hear the laughing, talk, and clinking of wine glasses mixed with the smell of good food that came from the banquets in the palaces. Then he would understand the prestige, beauty, and grandeur of Venice. Until today some of this still remains, and people from all over the world go to visit Venice, and most return charmed and enthused.

This picture comes to one’s mind listening to the life of St. Peter Orseolo, who was a Doge of Venice. The title doge is an archaic Italian way to say dux, chief. He was the chief, the duke of Venice. The doge had to be of a noble family and was elected by the famous Council of Ten. He wore a kind of tunic of purple silk and a special biretta on his head used only by the doges. The ensemble of this garb was quite imposing.

The bucintoro, a special ship used by the Doge for solemn occasions, goes out to sea surrounded by smaller regattas with the Venetian nobility |

Every year on Ascension Day, the doge celebrated the feast of “the marriage of Venice with the sea.” It was a symbolic marriage, of course, to signify that the very life of Venice relied on the sea. On this day the doge would travel to the high sea in a magnificent boat, as large as a small ship, called a bucintoro, or bucentaur. He was followed by numerous smaller, golden gondolas filled with the Venetian nobility. When the bucentaur reached the high sea, the doge threw a gold ring into the sea: the annual tribute to the marriage.

After this ceremony, he returned. When he reached Venice all the bells of the city were ringing, and in all the city squares there was song and dance, wine and food. It was a day of great joy for the people of Venice.

You have to imagine the future St. Peter Orseolo in such an ambience. He was, as you heard, very precocious. At age 20 he commanded a fleet to fight the pirates who were infesting the Adriatic Sea and shores of Venice. To fight pirates at that time was an important work. It would be more or less like fighting the hijackers who take over airplanes from South America and oblige them to land in Cuba. The pirates had ships, not planes, which they used to hijack the vessels of the civilized world – Venice included. They would steal the goods and cargo, and then take the Catholic crews and passengers to sell them to the Muslims as slaves in Africa or Asia.

So a passenger in one of these ships ran the risk of being captured by pirates, being deprived of the Sacraments, and spending the rest of his life as a slave of a sultan. Therefore, it was an important work of apostolate to fight the pirates. It was also a work that demanded great courage. Peter Orseolo, then, fought the pirates, conquered them, cleaned the Adriatic, and became famous for those feats.

Later, it seems that he took part in a revolution that set fire to and destroyed part of Venice and deposed the doge. The selection is insufficient and very unclear about these facts. I do not know the reason for the revolt, but it is strange to see a man, who supposedly was already good, taking part in a revolution. It is contrary to sanctity to be part of a revolution. Sanctity is supposed to support the law. St. Thomas Aquinas taught us that the revolutions, with some very rare exceptions, are illegitimate.

At any rate, he played some role in a revolution, perhaps as leader, and his party won. He faced all the dangers, deposed the old government, and arranged to be elected doge. For a while he governed Venice with an iron hand and reconstructed the buildings damaged by the fire. One can see he was quite well set in life. He was Doge of Venice, head of one of the most brilliant and wealthiest States of the time.

Above, The Return of the Bucintoro, top right, at the Ascension Day. Below, the event is still commemorate every year with two weeks of festivities and regattas for the marriage of the Doge with the sea.

|

Then came the mystery of grace. A man with such a steel temper, accustomed to conquer, dominate, and order suddenly was touched by grace. He recognized his sins and bad actions of the past and made the decision to abandon everything. He fled Venice secretly to prevent people from impeding him and traveled to a far away monastery. There he asked to be accepted as a monk. It was a complete change of scenario. The man who was a lion became a lamb; the governor who dominated a city became obedient; the prince who was brilliant and rich became a mere monk, with the simple life of saying the Divine Office, working the earth, reading and praying to God for forgiveness. It is a complete change.

In the profile of this monk, the figure of the doge began to fade to be replaced by the figure of the saint. His renunciation was blessed by God. Special graces poured over him. His virtue went beyond the common, and from a good monk he became a saint. He died admired by all, and soon the miracles multiplied on his tomb. Later he was canonized by the Church.

St. Orseolo bequeathed to us an idea of monk completely different from the one commonly spread by a certain sentimental piety. According to this piety, the monk is a soft, cheerful man, living a nice calm life without serious concerns; before dying he receives an ecstasy, understood as a last grand smile. This is not true.

The last phase of the life of St. Orseolo proved the opposite. He brought to the monastery his spirit of a fighter. Instead of fighting against pirates and political enemies, he embarked on a new and more difficult combat, the combat against himself. The man who is able to dominate himself must be an energetic man, because it is much more difficult to say “no” to oneself than to say “no” to others. The true saint is a hero. He has to practice all the virtues to a heroic degree. Every saint is a hero, but not every hero is a saint, since he still has some points in which he did not practice heroism.

These are some comments on the unusual life of St. Peter Orseolo. He left to History the Adriatic Sea free of pirates and Venice rebuilt. But much more than that, he left us the example of a true saint. Let us pray to St. Peter Orseolo asking him to give us the courage he had in the first part of his life so that we might face the enemies of the Church, and the courage he had in the second part of his life so we might fight against ourselves and our defects.

|

| Prof. Plinio Corrêa de Oliveira | |

The Saint of the Day features highlights from the lives of saints based on comments made by the late Prof. Plinio Corrêa de Oliveira. Following the example of St. John Bosco who used to make similar talks for the boys of his College, each evening it was Prof. Plinio’s custom to make a short commentary on the lives of the next day’s saint in a meeting for youth in order to encourage them in the practice of virtue and love for the Catholic Church. TIA thought that its readers could profit from these valuable commentaries.

The texts of both the biographical data and the comments come from personal notes taken by Atila S. Guimarães from 1964 to 1995. Given the fact that the source is a personal notebook, it is possible that at times the biographic notes transcribed here will not rigorously follow the original text read by Prof. Plinio. The commentaries have also been adapted and translated for TIA’s site.

|

Saint of the Day | Home | Books | CDs | Search | Contact Us | Donate

© 2002- Tradition in Action, Inc. All Rights Reserved

|

|

|