Organic Society

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Customary Law - II

The Barbarian Invasions

Molded a New Juridical Situation

During the 9th and 10th centuries, Europe was literally devastated by barbarian invasions coming from every direction. There were invasions of Hungarians, the remote descendents of the Huns, who swept through Germany with their small, rapid horses and ravaged it, then crossed over Austria and destroyed northern Italy. From there they passed over the mountains of Switzerland until they reached the heart of France and the Champagne region.

Then came the invasions of the Vikings, who originated from Scandinavia. They penetrated Europe via its rivers, burning, looting and causing devastation. They were so skillful as sailors that they crossed through all of Europe and ended by invading Constantinople. This demonstrates well the impetus and ferocity of that people.

Then came the invasions of the Vikings, who originated from Scandinavia. They penetrated Europe via its rivers, burning, looting and causing devastation. They were so skillful as sailors that they crossed through all of Europe and ended by invading Constantinople. This demonstrates well the impetus and ferocity of that people.

Another group of equestrian warrior nomads of Altaic extraction who invaded Central and Eastern Europe was the Avars, a people who later disappeared. Finally, we have the Saracens who entered France through the Pyrenees and crossed all of Italy.

These invasions – hostile to Europe and to one another – that came from every side literally broke Europe into pieces. When we speak of invasion, we normally imagine an assailing column that enters an area with a calculated agenda. Only what stands in the way of that pillaging column is devastated. This is not what happened with those hordes.

They were barbarians, they had no maps; they wandered without the aim of conquering a country but just of plundering it. They did not have any defined aim to stay and dwell in those lands they looted, nor did they have the clear intention to return to their places of origin. They just want to pillage and live from the land until they were ready to move on or were driven away by another group.

They were barbarians, they had no maps; they wandered without the aim of conquering a country but just of plundering it. They did not have any defined aim to stay and dwell in those lands they looted, nor did they have the clear intention to return to their places of origin. They just want to pillage and live from the land until they were ready to move on or were driven away by another group.

Now, you can imagine such hordes moving here and there through Europe, going back and forth in this way. A city could be ransacked by Hungarians, and then, shortly afterward, become the prey of Saracens or Vikings. Nobody could know for sure who would come to ravage the land, why they would come or when they would leave. It was impossible to plan anything simply because the invaders had no plan.

I ask you to put yourselves in the position of a king. Let us suppose the King of France is in Paris surrounded by barbarians. He is without telegraph, telephone or radio. He only knows what happens through messengers who arrive by horse to report to him what has happened in this or that place.

Two factors jeopardized this source of information: first, the messengers would be caught by the enemies and prevented from delivering their news to the King; second, the nobles stopped sending news since the King could not help them. The impossibility of him offering assistance is understandable. If the invasion were focused at a single point, he could gather together forces and send them there. But the fact that the hordes were entering everywhere made it impossible to plan any reasonable counter-attack.

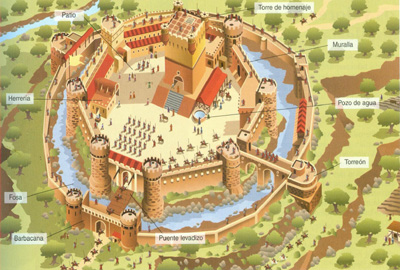

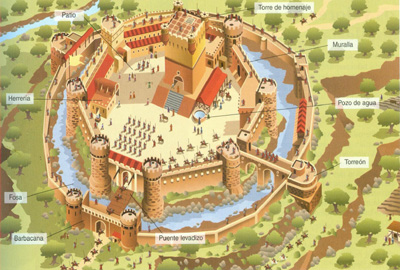

Therefore, the only resistance had to be local: strongholds were built to face the enemies and resist their sieges. Thus, France and Europe started to fill with castles to protect the families of the large landowners, their servants, their provisions and livestock.

Therefore, the only resistance had to be local: strongholds were built to face the enemies and resist their sieges. Thus, France and Europe started to fill with castles to protect the families of the large landowners, their servants, their provisions and livestock.

Now, imagine this situation continuing for a period of more or less two centuries. Imagine if our country had been continuously ravaged by barbarians for the last 200 years. It would be a phenomenon that would profoundly mark the physiognomy of the country. How did it mark Europe?

Everywhere the local landowners began to exercise their natural authority to maintain order and keep life going. The same thing happens, for example, when a ship goes off course in a storm without hope of returning. Its passengers make up a small social group with its own internal life, a tiny segment of mankind, and the captain ends by becoming a kind of king. He is the only one who knows how to direct the ship. The other forms of authority naturally fall to him, and he is the one who takes command. This is, analogically, how Feudalism was born in Europe.

I smile when I hear pseudo-historians make this kind of tirade: “In the dark ages of medieval times, the decadent Carolingian Kings were unable to hold the scepter of Charlemagne in their trembling hands, nor could their uncouth minds discern the thinking of the great founder of the Empire to preserve its unity.”

I would like to see what one of these critics would do with the scepter of Charlemagne if he were besieged by these ravaging hordes in the capital of the Kingdom. He would most probably flee, leaving the scepter in the road or selling it to a Jew. Regarding the demands of unity, I doubt he would even be thinking about them.

In other words, this was simply the way things were, what that brutal play of circumstances imposed.

Good sense versus sociology

Those men of the Middle Ages had an enormous advantage over us. They did not know Sociology. They did not have, therefore, the vice of recording statistics, studying them and resolving social problems that are not their own. In our times this has become a veritable mania, a kind of psychosis in contemporary society. We have crowds of such hunters of problems who pursue statistics in order to prove, first, that the problem exists and, only then, to seek solutions.

Medieval men were different: They did not make scholarly theories about society. They only had time to resolve their problems with the good sense of a person who lives his daily life, and nothing more. So, between invasions, they would sow and harvest because they needed wheat to not die of hunger; they had to dig a new well because in the last siege the previous one was destroyed or found to be insufficient. They needed to send help to an ally who was being attacked or else all would be killed and their own position weakened. In short, they did not have time for poetry, sociology and the making of laws and regulations.

Medieval men were different: They did not make scholarly theories about society. They only had time to resolve their problems with the good sense of a person who lives his daily life, and nothing more. So, between invasions, they would sow and harvest because they needed wheat to not die of hunger; they had to dig a new well because in the last siege the previous one was destroyed or found to be insufficient. They needed to send help to an ally who was being attacked or else all would be killed and their own position weakened. In short, they did not have time for poetry, sociology and the making of laws and regulations.

However, throughout those 200 years those people continued to live, buy, sell, make loans, and follow a whole juridical life. The juridical reality suffered the impact of the new situation.

This altered panorama is what decisively changed the system of law from written law to customary law.

Continued

The Hungarian or Magyar invasion ravaged a large part of Europe

Another group of equestrian warrior nomads of Altaic extraction who invaded Central and Eastern Europe was the Avars, a people who later disappeared. Finally, we have the Saracens who entered France through the Pyrenees and crossed all of Italy.

These invasions – hostile to Europe and to one another – that came from every side literally broke Europe into pieces. When we speak of invasion, we normally imagine an assailing column that enters an area with a calculated agenda. Only what stands in the way of that pillaging column is devastated. This is not what happened with those hordes.

Entering via the rivers, the Vikings constituted an uncertain and terrible danger for the people

Now, you can imagine such hordes moving here and there through Europe, going back and forth in this way. A city could be ransacked by Hungarians, and then, shortly afterward, become the prey of Saracens or Vikings. Nobody could know for sure who would come to ravage the land, why they would come or when they would leave. It was impossible to plan anything simply because the invaders had no plan.

I ask you to put yourselves in the position of a king. Let us suppose the King of France is in Paris surrounded by barbarians. He is without telegraph, telephone or radio. He only knows what happens through messengers who arrive by horse to report to him what has happened in this or that place.

Two factors jeopardized this source of information: first, the messengers would be caught by the enemies and prevented from delivering their news to the King; second, the nobles stopped sending news since the King could not help them. The impossibility of him offering assistance is understandable. If the invasion were focused at a single point, he could gather together forces and send them there. But the fact that the hordes were entering everywhere made it impossible to plan any reasonable counter-attack.

Now, imagine this situation continuing for a period of more or less two centuries. Imagine if our country had been continuously ravaged by barbarians for the last 200 years. It would be a phenomenon that would profoundly mark the physiognomy of the country. How did it mark Europe?

Everywhere the local landowners began to exercise their natural authority to maintain order and keep life going. The same thing happens, for example, when a ship goes off course in a storm without hope of returning. Its passengers make up a small social group with its own internal life, a tiny segment of mankind, and the captain ends by becoming a kind of king. He is the only one who knows how to direct the ship. The other forms of authority naturally fall to him, and he is the one who takes command. This is, analogically, how Feudalism was born in Europe.

I smile when I hear pseudo-historians make this kind of tirade: “In the dark ages of medieval times, the decadent Carolingian Kings were unable to hold the scepter of Charlemagne in their trembling hands, nor could their uncouth minds discern the thinking of the great founder of the Empire to preserve its unity.”

I would like to see what one of these critics would do with the scepter of Charlemagne if he were besieged by these ravaging hordes in the capital of the Kingdom. He would most probably flee, leaving the scepter in the road or selling it to a Jew. Regarding the demands of unity, I doubt he would even be thinking about them.

In other words, this was simply the way things were, what that brutal play of circumstances imposed.

Good sense versus sociology

Those men of the Middle Ages had an enormous advantage over us. They did not know Sociology. They did not have, therefore, the vice of recording statistics, studying them and resolving social problems that are not their own. In our times this has become a veritable mania, a kind of psychosis in contemporary society. We have crowds of such hunters of problems who pursue statistics in order to prove, first, that the problem exists and, only then, to seek solutions.

The building of the castles represented a complete change in the previous social and juridical order

However, throughout those 200 years those people continued to live, buy, sell, make loans, and follow a whole juridical life. The juridical reality suffered the impact of the new situation.

This altered panorama is what decisively changed the system of law from written law to customary law.

Continued

Posted July 21, 2014

Organic Society was a theme dear to the late Prof. Plinio Corrêa de Oliveira. He addressed this topic on countless occasions during his life - at times in lectures for the formation of his disciples, at times in meetings with friends who gathered to study the social aspects and history of Christendom, at times just in passing.

Prof. Plinio

Atila S. Guimarães selected excerpts of these lectures and conversations from the transcripts of tapes and his own personal notes. He translated and adapted them into articles for the TIA website. In these texts fidelity to the original ideas and words is kept as much as possible.

______________________

______________________