|

Organic Society

The Decay of the Medieval Guilds

Plinio Corrêa de Oliveira

In countries like the United States, there is a federation of states subdivided into counties and cities roughly similar to the distribution of political units in medieval Feudalism. These medieval units were governed by the great and middle nobility, as well as the small nobility, which was often municipal.

The nation was represented by the whole political organism encompassing the entire gamut of authorities – from the King at the top to the baron in the city. The State was progressively divided into smaller interrelated units.

In Feudalism, there were many intermediary societies between the State and the individual. These institutions were neither necessarily linked to the State nor restricted to an individual’s domain. In many ways they had their own autonomous power of government.

The medieval clockmakers reached a great perfection. From the top left, clockwise, the town clocks of Bern (Switzerland), Paris, Prague and Strasbourg (France) |

Take, for example, certain organizations of clockmakers in Switzerland. A family of clockmakers would establish its own workshop. Gradually, through several generations, that workshop would become a small industry, employing many workers to do various jobs under the direction of family members. The same process would take place in other families of clockmakers. Then, that group of families would normally develop a set of laws to govern that specific business. This statute, born from the needs of that industry and the relations between the owners and their employees, would aptly govern the industry of clockmakers in a specific area.

The clockmakers’ statute would be very different from that of the winemakers, the bookbinders, or the goldsmiths, since each different profession had its own organic development that would give rise to its own laws.

The medieval State used to recognize this restricted legislative power of the guilds. Each such particular code of law would apply to just one profession in a particular district or city.

One can see that such rules were made to protect and give stability to each trade and to those who worked in it. This is how the normal life of the guilds progressed in the ensemble of society. The guilds were respected and enjoyed a great autonomy.

The 'cyclone man'

This type of government accommodated the common man of the guilds, whom they benefited and helped. But they do not satisfy a type of 'cyclone man', the exceptional man with a great dynamism and strength of will. Such men have the capacity and means to be much more than the common man. The organic legislation of the guilds has the advantage of favoring the life of the average man in his profession. But it raises obstacles for the exceptional man, whom here I will call the 'cyclone man.' He does not fit well within the limits of those laws.

Is the 'cyclone man' a gift from God or a chastisement of God? It depends. If one gives every possible liberty to the 'cyclone man,' he can easily be a scourge of God. Consider the case of Winston Churchill, who was an exceptional man. Certainly his energetic will played an important role in preventing Europe from becoming Nazi, which was very good. However, he also played an important role in handing over a considerable part of Europe to Communism, which was very bad. So, the same man who is worthy of admiration in many aspects became a source of chastisement in many others.

This shows us that in a well-constituted society, there must be a social and juridical equilibrium that allows the possibility for the 'cyclone man' to ascend, but not without certain restraints. He must be controlled by a social and legal braking mechanism that will contain his bad sides.

Today’s liberal society, which adores the 'cyclone man,' is so constituted as to allow the cyclone man an almost free reign to reach the top. This is a characteristically American phenomenon.

Rotten bourgeois and revolted guilds

In their first phase, the guilds were healthy and used their restricted legislative powers in a balanced way. The guild head was very close to his workers, teaching them what to do and paternally keeping check on their work. After this phase, however, the heads increasingly assumed for themselves greater internal power, isolated the worker, and became excessively concerned over the profit margin of the business. This was the early seed of the unbridled capitalist who would follow.

The owner or master of the workshop began to distance himself from the workers, seeking exaggerated profits |

The guild head began to disproportionately accumulate money for himself and removed himself from the worker as if he were from a different social class. The bourgeois director, who was essentially as plebeian as the manual worker (both were men from the people), began pretending to be a noble and trying to arrange a marriage for his daughter with the baron’s or count’s son.

This attitude of the budding businessman created a disequilibrium inside two social classes: the people and the nobility. On the one hand, it produced an understandable discontent among the guild workers and even a revolt against the head, insofar as he exploited and despised the workers, pretending that he belonged to a different social class. On the other hand, his disproportionate profit made him very wealthy, wealthier than the regional noble, whose modest revenue came from his lands. This misplacement of wealth introduced instability inside the institution of the nobility. Instead of moral values being the criteria for making new nobles, money entered the picture. The nobles started to redorer leur blasons [to re-guild their shields], an expression that means giving one’s daughter in marriage to the son of a rich bourgeois in order to enrich the noble house with gold and help it to return to its old brilliance.

Adding to the social instability, a new economic power sprang up: the bourgeois began to offer money to the noble for his extra expenses such as wars, brilliant feasts, or just to keep up with the new fashions. In the beginning it was easy money with low interest rates. After a while, however, the interest increased, making the noble gradually more dependent on the bourgeois.

A cancer had entered the guilds’ life and metastasized into the nobility. The guild workers became revolted because of the new attitude of the bourgeois; the nobility became venal and increasingly entangled in financial debts.

A change of mentality in the guilds

This is the root of an unbridled Capitalism, which could easily be blamed for everything. There is something else, however, that we should consider. It is the role of the change of mentalities and principles inside the guilds.

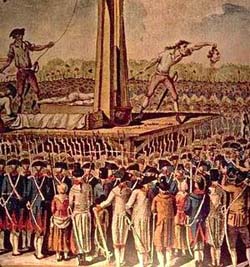

Top, Henri IV had to pretend a conversion to become King; bottom, the beheading of Louis XVI

|

When one studies how the guilds evolved and the exercise of power inside them, one sees that their chiefs made the same mistakes that the absolute Kings committed in their kingdoms. A bad wind swept through society, changing the mentalities at both its top and bottom. The nature of this change has not been sufficiently studied, but at the root of a psychological decay of institutions there is always a religious decay.

An upright spirit is what forms a healthy economy, and the decay of this spirit produces a bad economy. Since the true upright spirit comes only from the true Religion, it follows that religion is the base cause that moves men in one direction or another.

When the Valois dynasty ended in the 16th century, a Protestant candidate appeared for the Catholic throne of France, the Huguenot Henry of Navarre, who became Henry IV of France. At that time, the people of Paris, that is, the manual workers organized into guilds, were the strongest force opposing the Protestants. Henry IV had to pretend a conversion in order to ascend to the throne, given the strength of that corporative body of guilds representing the life of Paris. Parallel to the workers’ guilds was the Parliament of Paris, which was the guild of the juridical class that wielded enormous power and also supported the Catholic cause.

Some 200 years later, however, the principal force propelling the French Revolution was Paris, and in Paris, once again, the people and the Parliament organized into guilds.

What happened in those 200 years that caused the people of Paris, once the citadel of the Catholic monarchy, to become the citadel of the Revolution? What change occurred in the mentalities of those guilds which, at the time of Henry IV, had preserved the Kingdom of France, but 200 years later were destroying the Royalty? This is even more difficult to understand in that the French Revolution destroyed the organic life of guilds and the Parliament of Paris that had existed before. What came after were guilds emptied of life and tyrannically controlled.

Here, then, is the problem presented in its full clarity. We should keep it in mind as we look for a solution, a solution that I am still seeking.

Posted May 26, 2008

| | Prof. Plinio |

Organic Society was a theme dear to the late Prof. Plinio Corrêa de Oliveira. He addressed this topic on countless occasions during his life - at times in lectures for the formation of his disciples, at times in meetings with friends who gathered to study the social aspects and history of Christendom, at times just in passing.

Atila S. Guimarães selected excerpts of these lectures and conversations from the trancripts of tapes and his own personal notes. He translated and adapted them into articles for the TIA website. In these texts fidelity to the original ideas and words is kept as much as possible.

Related Topics of Interest

Respectability in the Medieval Professions Respectability in the Medieval Professions

Groups of Friends and Guilds Groups of Friends and Guilds

Proportion Between the City and the Man Proportion Between the City and the Man

The Clan and the Family The Clan and the Family

Clans and Human Types Clans and Human Types

Vocations of the European Peoples Vocations of the European Peoples

Revolution and Counter-Revolution in the Tendencies, Ideas, and Facts Revolution and Counter-Revolution in the Tendencies, Ideas, and Facts

|

Organic Society | Social-Political | Home | Books | CDs | Search | Contact Us

© 2002-

Tradition in Action, Inc. All Rights Reserved

|

|

|