Personalities

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Freud’s Religious & Philosophical Lacunae

Continuing on with my study of the main founders of Psychoanalysis, I will comment on some aspects of the work The Future of an Illusion written by Sigmund Freud in Vienna in the year 1927.

In this book Freud takes a cultural approach on the topic of religion instead of a clinical one. His last clinical-theoretical work had been The Ego and the Id, published in 1923. After that, he only wrote works on culture, civilization and religion: for example, his Civilization and its Discontents (1930) and Moses and Monotheism (1938) one year before his death.

As a confirmed atheist, Freud had an extremely negative view of religion, which he called an “illusion” and a “childhood neurosis.”

At the very beginning of the book, he affirms he does not intend to discuss the idea of God, but only what he called “religious ideas.”

He states that the idea of a God who punishes and rewards is nothing but a “childhood neurosis,” a vestige of the child each one of us has living in our unconscious.

In simpler words, let me explain what he is saying.

Principally in the first years of his life, every child feels abandonment, solitude and fear. He has a fear of darkness, annihilation, death, violent and dangerous animals.

It is the persons of the mother and, afterwards, the father, who protect the child from these fears. When the child cries because he is hungry or feels pain, it is the mother who comes to his succor. The mother or the one who plays that role – a sister, a grandmother, an aunt or another adult – gives him protection and affection. It is the mother who brings him food – milk; it is she who bathes him and sings lullabies to him; it is she who sits him on her lap, which means protection. In a word: It is the mother who comforts him.

It is the persons of the mother and, afterwards, the father, who protect the child from these fears. When the child cries because he is hungry or feels pain, it is the mother who comes to his succor. The mother or the one who plays that role – a sister, a grandmother, an aunt or another adult – gives him protection and affection. It is the mother who brings him food – milk; it is she who bathes him and sings lullabies to him; it is she who sits him on her lap, which means protection. In a word: It is the mother who comforts him.

I remember a young patient once told me that when he was a child he had great fear of sleeping alone. But he felt strong when his parents allowed him to move to their bed and sleep there with them.

Another patient told me that when he was with his father, he felt brave enough to cross a “dark forest,” since his father protected him from any evil.

Freud saw in these children’s needs the origin of the religious idea. Hence his affirmation that Religion is a childhood neurosis. What he meant by this was that, just as a child needs an adult to feel secure, so also when he becomes an adult he needs God to feel good. Religion, for Freud, would be nothing more than the vestiges of the child’s mindset that still lives in the adult man.

Thus, Freud reduced all mystical and religious experiences to psychoanalytic categories that he could study, control and disregard at will on the couch in his consulting room.

Thus, Freud reduced all mystical and religious experiences to psychoanalytic categories that he could study, control and disregard at will on the couch in his consulting room.

He went further. He stated without hesitation that the sole field of knowledge that can save man is science. At the end of his work he affirmed: “No, our science is no illusion. But it would be an illusion to think that what science cannot give us we can get elsewhere.”

This is the core of his thought.

For Freud, all the religious practices, all the quests of man for transcendence, all mystical experiences, all of Revelation in the Bible and Tradition are nothing but this: a childish desire to find in adulthood the security and well-being that his mother and his father gave him! It is a very deficient conception, to say the least.

Let us look at another example of Freud’s poor philosophy.

At times I ask myself: What would Freud think if he were living today? After the tragic 20th century with its two World Wars and the Sexual Revolution of the ‘60s with the lifting of all repressions, what would he say?

It is evident that the world did not get better. Instead, there was a strong decline in civilization. The world got much worse than it was at his time. But, according to Freud, this should not have happened. He affirmed that when there were no more repressions, when people became freer with more relaxed styles of dress and sexual liberty, then we would all be much happier.

But we are not. Never in History has man been prescribed so many psychiatric medications as today. Never has he had so much anxiety, anguish and depression as today.

Freud erred. His philosophy that sexual freedom and the advancement of the sciences would bring

great progress in mental health was completely wrong.

But we are not. Never in History has man been prescribed so many psychiatric medications as today. Never has he had so much anxiety, anguish and depression as today.

Freud erred. His philosophy that sexual freedom and the advancement of the sciences would bring

great progress in mental health was completely wrong.

As I have mentioned before, Freud was strongly influenced by Auguste Comte, the founder of Positivism. Positivism refers to the experimental knowledge man receives from external natural phenomena that can be known by the senses. According to this theory, man is incapable of knowing the inner nature and causes of things. He must content himself with knowing the observable laws that govern the existence of things. The so-called philosophy of Positivism rejects as valueless any conception different from this. It refers, therefore, to the so-called natural sciences.

Freud as well as Comte believed that the cure of all the evils of mankind would come through science.

No doubt that there was much scientific progress in the 19th century. These include, for example, the discovery of radioactivity; the establishment of the laws of electricity; an understanding of many natural elements that gave birth to chemistry; the foundations for neurology and biology were also laid during that epoch.

No doubt that there was much scientific progress in the 19th century. These include, for example, the discovery of radioactivity; the establishment of the laws of electricity; an understanding of many natural elements that gave birth to chemistry; the foundations for neurology and biology were also laid during that epoch.

One would expect that a sound philosophy would enter to support these discoveries. Unfortunately, that philosophy was Positivism, which is in itself a contradiction in terms. Indeed, when the base of Positivism is admittedly only what happens in the external physical sphere, it is implicitly affirmed that the metaphysical sphere does not exist, or at the least does not matter. Now then, since a philosophy by definition is an abstract ensemble of metaphysical knowledge, it follows that Positivism is a denial of all philosophy.

Freud agreed with Comte in this regard. He expressed a hatred for philosophy. In talks with his friends he warned them to not allow Psychoanalysis be transformed into Philosophy. Jung confirms this concern of Freud in his book Memories, Dream, Reflections.

Freud treasured science as the sole form of knowledge. He dismissed, therefore, philosophy, religion, art and even common sense as other ways to acquire knowledge. He denied any other field of knowledge but science. It is not so different from being partially blind.

The approach of Freud toward reality was, therefore, highly superficial and surprisingly simplistic. To reduce religion to children’s memories is absolutely inadmissible.

Continued

In this book Freud takes a cultural approach on the topic of religion instead of a clinical one. His last clinical-theoretical work had been The Ego and the Id, published in 1923. After that, he only wrote works on culture, civilization and religion: for example, his Civilization and its Discontents (1930) and Moses and Monotheism (1938) one year before his death.

As a confirmed atheist, Freud had an extremely negative view of religion, which he called an “illusion” and a “childhood neurosis.”

At the very beginning of the book, he affirms he does not intend to discuss the idea of God, but only what he called “religious ideas.”

He states that the idea of a God who punishes and rewards is nothing but a “childhood neurosis,” a vestige of the child each one of us has living in our unconscious.

In simpler words, let me explain what he is saying.

Principally in the first years of his life, every child feels abandonment, solitude and fear. He has a fear of darkness, annihilation, death, violent and dangerous animals.

The protection of her mother lets the girl know the world

I remember a young patient once told me that when he was a child he had great fear of sleeping alone. But he felt strong when his parents allowed him to move to their bed and sleep there with them.

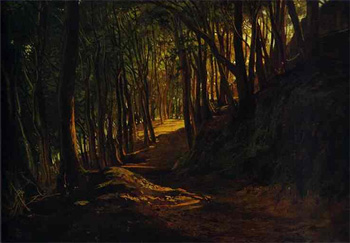

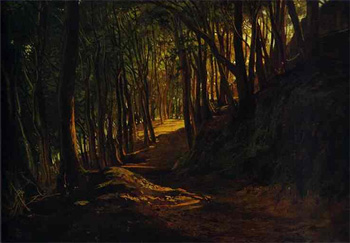

Another patient told me that when he was with his father, he felt brave enough to cross a “dark forest,” since his father protected him from any evil.

Freud saw in these children’s needs the origin of the religious idea. Hence his affirmation that Religion is a childhood neurosis. What he meant by this was that, just as a child needs an adult to feel secure, so also when he becomes an adult he needs God to feel good. Religion, for Freud, would be nothing more than the vestiges of the child’s mindset that still lives in the adult man.

A boy can cross a dark forest without fear when he is with his father

He went further. He stated without hesitation that the sole field of knowledge that can save man is science. At the end of his work he affirmed: “No, our science is no illusion. But it would be an illusion to think that what science cannot give us we can get elsewhere.”

This is the core of his thought.

For Freud, all the religious practices, all the quests of man for transcendence, all mystical experiences, all of Revelation in the Bible and Tradition are nothing but this: a childish desire to find in adulthood the security and well-being that his mother and his father gave him! It is a very deficient conception, to say the least.

Let us look at another example of Freud’s poor philosophy.

At times I ask myself: What would Freud think if he were living today? After the tragic 20th century with its two World Wars and the Sexual Revolution of the ‘60s with the lifting of all repressions, what would he say?

It is evident that the world did not get better. Instead, there was a strong decline in civilization. The world got much worse than it was at his time. But, according to Freud, this should not have happened. He affirmed that when there were no more repressions, when people became freer with more relaxed styles of dress and sexual liberty, then we would all be much happier.

History has never seen so much anxiety, anguish and depression as we have today

As I have mentioned before, Freud was strongly influenced by Auguste Comte, the founder of Positivism. Positivism refers to the experimental knowledge man receives from external natural phenomena that can be known by the senses. According to this theory, man is incapable of knowing the inner nature and causes of things. He must content himself with knowing the observable laws that govern the existence of things. The so-called philosophy of Positivism rejects as valueless any conception different from this. It refers, therefore, to the so-called natural sciences.

Freud as well as Comte believed that the cure of all the evils of mankind would come through science.

Auguste Comte, founder of Positivism

One would expect that a sound philosophy would enter to support these discoveries. Unfortunately, that philosophy was Positivism, which is in itself a contradiction in terms. Indeed, when the base of Positivism is admittedly only what happens in the external physical sphere, it is implicitly affirmed that the metaphysical sphere does not exist, or at the least does not matter. Now then, since a philosophy by definition is an abstract ensemble of metaphysical knowledge, it follows that Positivism is a denial of all philosophy.

Freud agreed with Comte in this regard. He expressed a hatred for philosophy. In talks with his friends he warned them to not allow Psychoanalysis be transformed into Philosophy. Jung confirms this concern of Freud in his book Memories, Dream, Reflections.

Freud treasured science as the sole form of knowledge. He dismissed, therefore, philosophy, religion, art and even common sense as other ways to acquire knowledge. He denied any other field of knowledge but science. It is not so different from being partially blind.

The approach of Freud toward reality was, therefore, highly superficial and surprisingly simplistic. To reduce religion to children’s memories is absolutely inadmissible.

Continued

Posted May 8, 2020

______________________

______________________