Personalities

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Overview on Jung’s Work

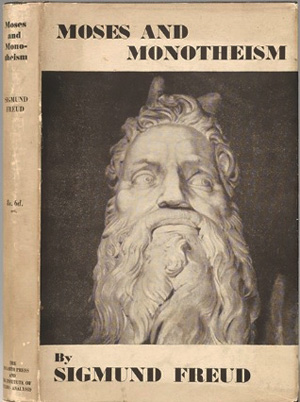

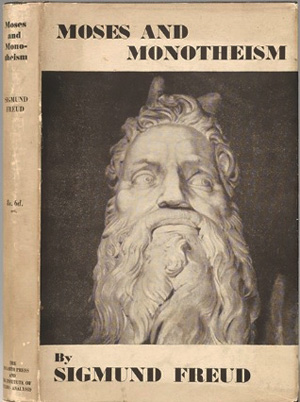

A brief initial note on Freud and religion: There is no report of Freud’s links with religion either during his long life – he died at age 83 – or at the hour of his death. On the contrary, he infuriated European rabbis because in his book Moses and Monotheism written in 1938 when he was already in England, he affirmed that Moses was not Hebrew but Egyptian. The work caused great turmoil among both Jews and Christians.

So, with one stroke of his pen, he denied the Bible and the Torah.

So, with one stroke of his pen, he denied the Bible and the Torah.

Nor did he provide any solid argument to prove his statement that Moses was not a Jew. His reason for such a bombastic declaration remains in the realm of mystery.

The first reaction of the rabbis was a decision to ban him from Judaism; they ended, however, by not doing so because of the growing Nazism in Europe with its persecution of Jews. To condemn Freud, who was a known scholar, would increase the animosity against the rabbis.

Having thus confirmed Freud's anti-religious attitude, let me continue on to deal with Jung.

Scholarly phase

Different from his master, Carl Jung was a religious child and youth. His father was a pastor in the Swiss Reformed Church and he grew up attending an evangelical service every week. The reading of the Bible was mandatory in his house and his father often tested him on biblical episodes. In his book Memories, Dreams, Reflections he mentions this phase in his life.

This religious sentiment faded away sharply when Jung began to study medicine at the University of Basel in 1895. In those years he dived into studies of anatomy, physiology and the other disciplines of the medical curriculum. But, as he affirmed in the mentioned Memoirs, his “interest for the mysteries of the human soul” continued in his subconscious.

After a specialization in Psychiatry, he graduated in 1900 and started to work at Burghölzli Psychiatric Hospital in Zurich. This was when he entered into contact with Freud, as I have mentioned in previous articles (here and here). He was 30 when he met Freud in 1906 in Vienna. At that first meeting they talked almost unceasingly for 13 hours, and the meeting turned into a close friendship. Indeed, even the spouses of both Freud and Jung became friends, writing frequent letters to each other and exchanging family photos.

On a trip to the United States in 1909, Jung traveled with Freud, who in his lectures would always give a sexual tonus to the etiology (origin) of his clinical cases. Jung, however, disagreed with this focus, considering that the problems of patients were produced by other causes, primarily religious frustrations. This initial discordance between Freud’s Atheism and Jung’s Protestant notions would generate their separation.

On a trip to the United States in 1909, Jung traveled with Freud, who in his lectures would always give a sexual tonus to the etiology (origin) of his clinical cases. Jung, however, disagreed with this focus, considering that the problems of patients were produced by other causes, primarily religious frustrations. This initial discordance between Freud’s Atheism and Jung’s Protestant notions would generate their separation.

In that time, however, Jung did not openly clash with his authoritarian master. In his Memoirs he described the acute personal dilemma he had to face. He admitted that at that time he even thought he would go mad, so great were his scientific and existential doubts. At the same time, he feared that opposing his master Freud was also madness. During this crisis, which took place between the years 1910 and 1913, his health deteriorated to the point Jung’s wife became very concerned.

Finally, he wrote a work affirming the importance of religion for the healthy life of men and especially for his patients. It was the publication of this book Psychology of the Unconscious that led to the break with Freud.

Freud frontally censured him with rough language and demanded that he reconsider his conclusions. In his book History of Psychoanalysis (1914), he openly refused to accept any changes to his science, affirming: “Psychoanalysis is my discovery.” When Jung refused to retract, Freud expelled him from the Psychoanalysis Society.

Freud frontally censured him with rough language and demanded that he reconsider his conclusions. In his book History of Psychoanalysis (1914), he openly refused to accept any changes to his science, affirming: “Psychoanalysis is my discovery.” When Jung refused to retract, Freud expelled him from the Psychoanalysis Society.

After this rupture, Jung began to publish journal articles and books, which were well accepted by many scholars. His books include: Psychology of the Unconscious, Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious, Psychological Types, The Relations between the Ego & the Unconscious and The Complexes & the Unconscious.

In 1934, he was invited to give a series of lectures in the Tavistock Clinic in London that were published in a collection titled Tavistock Lectures (1936). He criticized Nazi Germany and National Socialism affirming, for example that “the Jewish collective unconscious is much older than that of the Germans.” This position caused his works to be prohibited throughout the German Reich and he was forbidden to enter the country.

Jung's entire work was published in 24 volumes in Zurich in what is called the Standard Edition.

Esoteric phase

After World War II, Jung started to fall under the influence of Gnostic authors and theories. He engaged in studies of alchemy and began to entertain heresies like those of the Cathars and Albigensians. He wrote heavy and difficult-to-understand hermetic books, and was rightly accused of obscurantism.

His books Aion, Researches into the Phenomenology of the Self and Seven Sermons to the Dead as well as his concepts of the Hermetic Law of Correspondence and Pleroma, constituted part of his new “philosophical” interest. He also studied polytheist ancient cults like the Egyptian religion with its gods Osiris and Set, and even contributed Forewords to books on Zen Buddhism, Holy Men of India and the I Ching, Chinese book of divinations.

His books Aion, Researches into the Phenomenology of the Self and Seven Sermons to the Dead as well as his concepts of the Hermetic Law of Correspondence and Pleroma, constituted part of his new “philosophical” interest. He also studied polytheist ancient cults like the Egyptian religion with its gods Osiris and Set, and even contributed Forewords to books on Zen Buddhism, Holy Men of India and the I Ching, Chinese book of divinations.

Jung wrote extensively on these subjects in books that were tiresome and difficult reads. In this phase, he lost the scholarly standing he had acquired as an eminent psychologist.

Jung never bothered to study philosophy, neither the Greek philosophers nor Catholic Patrology and Scholasticism. Because of his dismal ignorance of St. Augustine and St. Thomas, he makes ridiculous affirmations, as in his Studies on the Trinity. Incidentally, this was the subject of my master's thesis in Clinical Psychology in the Pontifical Catholic University of São Paulo.

In conclusion, I would affirm that the work of Carl Jung is a mixture of useful truths for the study and treatment of mental illnesses and grave philosophical-gnostic errors that taint his thinking. Although he made some important discoveries, he entered the ranks of History as an esoteric author rather than a serious intellectual.

Continued

Freud angered Jews & Christians with his unfounded statement that Moses was Egyptian

Nor did he provide any solid argument to prove his statement that Moses was not a Jew. His reason for such a bombastic declaration remains in the realm of mystery.

The first reaction of the rabbis was a decision to ban him from Judaism; they ended, however, by not doing so because of the growing Nazism in Europe with its persecution of Jews. To condemn Freud, who was a known scholar, would increase the animosity against the rabbis.

Having thus confirmed Freud's anti-religious attitude, let me continue on to deal with Jung.

Scholarly phase

Different from his master, Carl Jung was a religious child and youth. His father was a pastor in the Swiss Reformed Church and he grew up attending an evangelical service every week. The reading of the Bible was mandatory in his house and his father often tested him on biblical episodes. In his book Memories, Dreams, Reflections he mentions this phase in his life.

This religious sentiment faded away sharply when Jung began to study medicine at the University of Basel in 1895. In those years he dived into studies of anatomy, physiology and the other disciplines of the medical curriculum. But, as he affirmed in the mentioned Memoirs, his “interest for the mysteries of the human soul” continued in his subconscious.

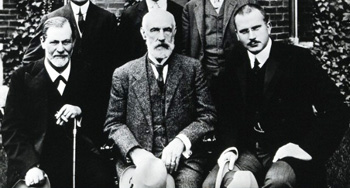

After a specialization in Psychiatry, he graduated in 1900 and started to work at Burghölzli Psychiatric Hospital in Zurich. This was when he entered into contact with Freud, as I have mentioned in previous articles (here and here). He was 30 when he met Freud in 1906 in Vienna. At that first meeting they talked almost unceasingly for 13 hours, and the meeting turned into a close friendship. Indeed, even the spouses of both Freud and Jung became friends, writing frequent letters to each other and exchanging family photos.

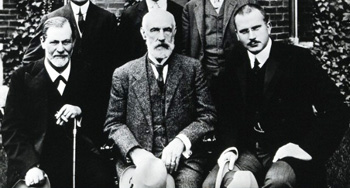

Mentor Freud, at left, & student Jung, at right, during the first phase of their relationship

In that time, however, Jung did not openly clash with his authoritarian master. In his Memoirs he described the acute personal dilemma he had to face. He admitted that at that time he even thought he would go mad, so great were his scientific and existential doubts. At the same time, he feared that opposing his master Freud was also madness. During this crisis, which took place between the years 1910 and 1913, his health deteriorated to the point Jung’s wife became very concerned.

Finally, he wrote a work affirming the importance of religion for the healthy life of men and especially for his patients. It was the publication of this book Psychology of the Unconscious that led to the break with Freud.

Jung's works were well accepted until he entered his 'esoteric phase'

After this rupture, Jung began to publish journal articles and books, which were well accepted by many scholars. His books include: Psychology of the Unconscious, Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious, Psychological Types, The Relations between the Ego & the Unconscious and The Complexes & the Unconscious.

In 1934, he was invited to give a series of lectures in the Tavistock Clinic in London that were published in a collection titled Tavistock Lectures (1936). He criticized Nazi Germany and National Socialism affirming, for example that “the Jewish collective unconscious is much older than that of the Germans.” This position caused his works to be prohibited throughout the German Reich and he was forbidden to enter the country.

Jung's entire work was published in 24 volumes in Zurich in what is called the Standard Edition.

Esoteric phase

After World War II, Jung started to fall under the influence of Gnostic authors and theories. He engaged in studies of alchemy and began to entertain heresies like those of the Cathars and Albigensians. He wrote heavy and difficult-to-understand hermetic books, and was rightly accused of obscurantism.

Jung drifted into a confused gnostic world of thought

Jung wrote extensively on these subjects in books that were tiresome and difficult reads. In this phase, he lost the scholarly standing he had acquired as an eminent psychologist.

Jung never bothered to study philosophy, neither the Greek philosophers nor Catholic Patrology and Scholasticism. Because of his dismal ignorance of St. Augustine and St. Thomas, he makes ridiculous affirmations, as in his Studies on the Trinity. Incidentally, this was the subject of my master's thesis in Clinical Psychology in the Pontifical Catholic University of São Paulo.

In conclusion, I would affirm that the work of Carl Jung is a mixture of useful truths for the study and treatment of mental illnesses and grave philosophical-gnostic errors that taint his thinking. Although he made some important discoveries, he entered the ranks of History as an esoteric author rather than a serious intellectual.

Continued

Posted April 17, 2020

______________________

______________________