|

Formation of Children

A Manual of Civility for Youth

Marian T. Horvat

Recently I received a Small Manual of Civility for Youth kindly sent to me by good friends. It was used in the Catholic high schools of Brazil in the ‘50s and ‘60s for the formation of young men. On the front is a quote from Fenelon: It is virtue that generates true courtesy. And another from Pope Leo XIII: Civility and urbanity in customs strongly predispose minds to attain wisdom and follow the light of truth. This gives a small taste of the delightful lost fruit one finds on the pages inside.

In an illustration from the Manual, a young man shows the proper way to sit and cut meat at the table |

I say lost fruit because the kind of manners the Small Manual sets out have fallen into such disuse that they are very rarely found today. Most modern men extol what is spontaneous and easy; the Catholic gentleman of the past measured his every act and word. The modern man treats every man, woman and child equally; civility moved the Catholic man to honor his neighbor with the respect and esteem owed to him, taking into account the factors of gender, status, rank and profession. In short, this is a manual from the old European school, something I have sought for some time.

I have found that the English-written manners books are practical, usually a set of rules of etiquette. The older ones like Emily Post give detailed instructions on how to eat properly, make introductions, write invitations, and so on. As with most rule books, these readings can be somewhat slow and monotonous. The contents are more about setting out norms rather than forming the entire man and imparting civility as a virtue.

I don’t even consider the more recent etiquette books, which tend toward a loose, casual style and have “adapted” the rules to meet the low morals of our day: how to announce the divorce announcement, stepsiblings do’s and don’ts, birth announcements for a single woman ...

This Manual for Youth is simple and unpretentious in style even while it maintains a ceremonial, respectful attitude. It understands civility as much more than following rules. First and foremost, it insists, civility is the knowledge and practice of the rules of good treatment that men should observe in relations of domestic and social life. No, it is not just “company behavior” rules one learns in order to keep a good reputation and get ahead in life. It is a way of being to adopt both at home and in public.

For example, in the introduction, the youth is warned: The uncivil man will be the object of criticism and sarcasm and his presence inopportune. And the reason for this rejection by good society? Because his external ways of being and acting reveal the lowness of his soul. Good, pure, and ordered customs reveal a man of good character. Bad, vulgar, and sloppy ways are the appanage of egoists.

It continues: True civility is a virtue. It allows us to be master of ourselves, because it demands an assiduous vigilance over words, gestures, and actions. It is the day-to-day victory that forms good character, a principal element of sociability.

I am finding the handbook most instructive, charming and even enlightening. Part One is titled “The well-raised man,” and there are chapters on how one should order his gaze, smile, laughter, and tone of voice as well as norms regarding discretion, modesty, loyalty and distinction. Each chapter ends with a small story section with examples from History or Scriptures that support the lesson. Or, as in the case of one of the first chapters that define civility, politeness, courtesy, and rusticity, there are these practical applications of the definitions for students that are useful for us Americans to know:

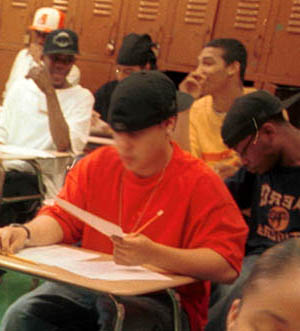

Above, the good posture of the students in a classroom half a century ago. The teacher sets the example.

Below, in this classrom typical of our times, young men slouch, whisper to friends, and wear hats indoors.

|

Civil: the youth who has a natural, erect stance, resting the weight of his body equally over his two feet. He holds his head straight, slightly inclined to the front, with his feet almost together at the heels and slightly open at the toes.

Uncivil: the youth who, when standing, shifts the weight of his body from one side to another, who leans against some piece of furniture or inclines his head to one side or another.

Courteous: the young man who has a firm upper body when seated; he leans neither backward nor forward on the chair. He keeps his feet straight in front of him.

Discourteous: the one who slouches back on the chair, who carelessly extends or swings his legs, or sets his feet one on top of the other, or who puts his elbow on the knee to rest his head on his hand.

Polite: the student who remains quiet in his seat so as not to bother his companions.

Impolite: the one who thoughtlessly rocks back and forth on his chair, at times just to bother his colleagues.

Rustic: the young man incapable of walking without making a ruckus, who does not wash his face or hands when he wakes up, who uses saliva to get out dirty spots on his clothes, who scratches himself or combs his hair in public, who picks his teeth with his fingers or looks in his handkerchief after blowing his nose.

As one can see, being polite and courteous is not limited to learning to say "Please" and "thank you." Rather, it reflects in the deportment and bearing of the young man. It involves the whole person and the first impression he makes. Quite obviously, we are in the presence of almost abandoned "old school" rules, most closely approximated in our country by the refined manners of the courteous and well-bred Southern gentleman.

Part Two looks at “The social man,” that is, a person’s relations with others in society. There is a profound awareness of social hierarchy and status in this Catholic manual that I have never found in American etiquette books. Perhaps it is because even our protocol books fear offending the egalitarian sensibilities of many Americans.

To the contrary, this manual instructs the youth that one of the most important points in the matter of civility is the art of treating each one according to the dignity, precedence and merits that he has acquired. It is the exact opposite of the boast of the egalitarian man: “I don’t care who he or she is. I treat everyone the same.”

We are offered the example of the behavior of a nobleman in France, the Prince of Talleyrand, renowned for his courtesy in dealing with others. At a dinner in his home with members of noble society, he served the beef that he had sliced at the table. He offered portions of this main meat to each of his guests with different nuances of address and tone:

To the guest of honor, the brother of the King, he said, “Monseigneur, would you do me the great honor of accepting a slice of beef?”

To the second in stature, he said: “Monsieur Duke, could I have the great joy of offering you this slice of beef?”

To the third, he said, “Monsieur Marquis, would you give me the pleasure of accepting this slice?”

To the fourth, “My dear Count, would you please permit me?”

To the fifth, “Baron, may I serve you beef?”

To the sixth, “Chevalier, would you like some?

To the seventh, “And what about you, Montrond?”

Finally, to the eighth: “Durand, beef?"

As one sees, the addresses and offers of servings of beef were graduated according to the social levels of the guests. Stories like this raise the admiration of those with the Catholic spirit and help us understand how things were in a hierarchical society.

Such incidents both fascinate and startle many young parents today who have little to no idea about the refined, disciplined customs of our glorious Catholic past. These relatively young men and women are realizing the importance of civility for maintaining the cordiality and well-being of family life, but they are also acutely aware of the lacunas in their own formation. In fact, many of these good-willed parents are themselves the children of the hippy generation, those "free-spirited" minds who cast aside all the rules and declared war on norms and formalities. Now they are returning to the good path of civilization.

It seems to me that this Small Manual of Civility is exactly what they have been looking for. There is, however, an obstacle, but not an insurmountable one. The book is in Portuguese. Therefore, to assist the many readers who have been asking me for Catholic rules of civility, I plan to offer them a small part every few weeks from this manual, along with some commentary.

I imagine it will give an assistance to all, but especially to the men who truly desire to see a restoration of Christian Civilization in the customs, manners and ways of being, which have been systematically smashed and destroyed by the Revolution, especially after World War II.

Posted July 27, 2006

Related Topics of Interest

Chapter 2: Bearing Chapter 2: Bearing

Chapter 3: How to Sit, Stand, Walk Chapter 3: How to Sit, Stand, Walk

Chapter 4: Order and the Spirit of Order Chapter 4: Order and the Spirit of Order

Chapter 5: Order in the Professional Life Chapter 5: Order in the Professional Life

Chapter 6: The Eyes and the Gaze Chapter 6: The Eyes and the Gaze

Dressing Well - Vanity or Virtue? Dressing Well - Vanity or Virtue?

St. Isidore of Seville on the Importance of Being Dignified in Manner St. Isidore of Seville on the Importance of Being Dignified in Manner

Four Ways to Discern a Man's Soul by His Appearance Four Ways to Discern a Man's Soul by His Appearance

Related Works of Interest

|

|

Formation | Cultural |

Home | Books | CDs

| Search | Contact Us

| Donate

© 2002- Tradition in Action, Inc. All Rights Reserved

|

|

|