About the Church

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The Holy Mass – Part I

The Early History of the Mass

The first Holy Mass, the chief and central act of Catholic worship, was said on the same night on which Our Lord was betrayed by Judas (cf. 1 Cor 11:23). On Holy Thursday the 12 Apostles had gathered with Our Lord for the paschal meal. The Last Supper certainly was one of the most important events in History.

After the washing of the feet, they came to the table for the supper. Then, Our Lord took bread into his Hands, looked up to heaven, gave thanks, blessed and broke it and gave it to His Apostles saying: “Take ye and eat. This is My Body.”

And after the Apostles had received the Body of Christ, He took the chalice in which was wine, gave thanks, blessed it and gave it to His Apostles saying: “Drink ye all of this for this is My Blood, the Blood of the new and eternal Covenant, the Mystery of Faith which shall be shed for you and for many for the remission of sins. Do this in memory of Me.” (1)

And after the Apostles had received the Body of Christ, He took the chalice in which was wine, gave thanks, blessed it and gave it to His Apostles saying: “Drink ye all of this for this is My Blood, the Blood of the new and eternal Covenant, the Mystery of Faith which shall be shed for you and for many for the remission of sins. Do this in memory of Me.” (1)

Thus, it was Christ himself who gave the essential core of Holy Sacrifice of the Mass, who established the words of the act of the Transubstantiation, that central moment when the unleavened bread and wine were transformed into the Body and Blood of Christ and, then, elevated them in the sight of the Apostles, who represented the whole Church, Hierarchy and faithful.

The New Testament clearly reflects the origin of the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass in written accounts of the Last Supper (Matt 26:26-28, Mark 14:23-24, Lk 23:19-20, Cor 11:23-25). Sacred Tradition and the Extraordinary Magisterium clearly substantiated Sacred Scripture.

Importantly, Our Lord said at the Last Supper in Aramaic the words “Mystery of Faith” or Mysterium Fidei, in Latin. This formula was always used in the Tridentine Mass, but was removed from the ICEL Novus Ordo Missae. Mysterium Fidei is the heart of the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass, the Transubstantiation. The absence of this formula was gladly accepted by the Protestants, interpreted by them as a denial of the Real Presence. (2)

Also, many modern liturgists deny that the first Mass occurred on Holy Thursday, a position that repeats exactly that taken at the time of the Protestant Revolution. The Protestants consider the first Mass to be on Good Friday, thus turning the ‘eucharistic supper’ of Holy Thursday into nothing more than a commemorative meal. This is also a position that was adopted by progressivists in the New Mass, which abolished the sacrificial character of the Mass and give emphasis to it as a memorial supper.

An unbloody Sacrifice

At the last Supper on Holy Thursday, Our Lord Jesus Christ instituted the visible unbloody sacrifice of the Mass in order to represent the bloody sacrifice that He would offer on Good Friday on the Cross, where all of His Blood was shed for the redemption of mankind until the end of the world. The setting for the first Mass was significant: the paschal lamb meal that the Jews celebrated every year was to recall the exodus from Egypt and to prefigure the great expectation of the Redemption.

The words Our Lord used at the Last Supper were quite similar to those which Moses spoke on the institution of the Old Covenant. After Moses revealed the law of sacrifice on Mount Sinai, he slaughtered an animal and sprinkled the blood upon the people, saying: “This is the blood of the covenant which the Lord hast made with you.” (Ex 24:8)

The words Our Lord used at the Last Supper were quite similar to those which Moses spoke on the institution of the Old Covenant. After Moses revealed the law of sacrifice on Mount Sinai, he slaughtered an animal and sprinkled the blood upon the people, saying: “This is the blood of the covenant which the Lord hast made with you.” (Ex 24:8)

The sacrifice of Moses was a prelude of Our Lord's Passion and Death. Jesus Christ desired that His Passion and Death should follow immediately after the Last Supper, signifying that they were one and the same act. The sacrifice in the Holy Mass begins at the consecration of the bread and wine into the Body, Blood, Soul and Divinity of Our Lord, the Transubstantiation, which is the very heart of the Mass.

According to the Venerable Mary of Agreda in The Mystical City of God, the Infant Jesus was transfixed after the Angel Gabriel placed Him in the arms of Our Lady. He revealed to His Mother the details of the Last Supper, His Passion and Death, and the sword of sorrow that would pierce her heart. Seven days after the Nativity at the Circumcision, He shed the first drops of His Precious Blood – enough to redeem mankind according to Ven Mary of Agreda. But, by the Divine Plan He was to shed all of His Precious Blood for our redemption.

At the Last Supper Our Lord transmitted to the Apostles the power to transubstantiate with the words: “Do this in memory of Me,” and all priestly successors also have this miraculous power (Council of Trent 22, 1).

The first Sacramentaries

In the first three centuries, Greek was the liturgical language at Rome and the names used for the whole sacrifice of the Mass were Eucharistia, or Eucharist, translated from Greek to Latin it is Divina Sacrificia or Divine Sacrifice, and Sacrificia Dei meaning Sacrifice of God.

In the year 88, the fourth Pope, St. Clement of Rome, martyr, wrote in his letter to the Corinthinians that Our Lord laid down the order of the Mass, referring specifically to the Offertory, Consecration and Communion. St. Clement made it clear this order was established by Christ: "We must do all things that the Lord told us to do at stated times” (Chapter xi). (3)

From the first century the services of the Church were performed in a fixed order with exact formulae; there is a graduated hierarchy, and the function of the clergy is clearly distinguished from the role of the laity. (4)

From the first century the services of the Church were performed in a fixed order with exact formulae; there is a graduated hierarchy, and the function of the clergy is clearly distinguished from the role of the laity. (4)

In the second century, St. Justin, martyr, wrote that after His Resurrection, Our Lord taught the Apostles how to say the Mass. St. Justin gave an open and complete account of the whole service and of its meaning, attributing the rite to Our Lord's institution as contained in the Gospels. (5)

It is generally held that the writings of St. Clement and St. Justin were formally expressed by St. Ambrose circa 387 AD in a book entitled De Sacramentis, which reiterated that the essential parts of the Mass are the Offertory, the Consecration and the Communion and was undertaken to form a uniform, unchanging Canon. It was in this century that Latin became the official language of the Church and the word Missa was introduced by St. Ambrose. To this day the Eastern Rites use the word Liturgia for the Holy Sacrifice.

The Leonine Sacramentary by Pope Leo the Great in the year 450, the essential parts of the Mass were the same as the form found in the Tridentine Mass. The Gelasian Sacramentary of Pope Gelasius I in 496 made the same order and formulae even clearer. There we find the same Canon as we had until Vatican II.

During the very important reign of Pope Gregory I, known as Gregory the Great, at the end of the 6th century (590-604), the finishing touches of the Mass were put on his Gregorian Sacramentary, which is essentially the same Mass codified by the Council of Trent (1545-1563), 10 centuries later, for the Ordinary of the Mass. The Mass Propers, the scriptural texts that change daily with the liturgical calendar, of course had many additions over the years.

From this history, summarily presented here, there is one important fact to be stated by Fr. Adrian Fortescue in his landmark study on the Mass, and underscored by us: “From roughly the time of St. Gregory [d. 604] we have the text of the Mass, its order and arrangement, as a sacred tradition that no one has ventured to touch except in unimportant details."

This statement was true until Vatican Council II.

Continued

After the washing of the feet, they came to the table for the supper. Then, Our Lord took bread into his Hands, looked up to heaven, gave thanks, blessed and broke it and gave it to His Apostles saying: “Take ye and eat. This is My Body.”

The Mass was instituted by Christ at the

Last Supper on Holy Thursday

Thus, it was Christ himself who gave the essential core of Holy Sacrifice of the Mass, who established the words of the act of the Transubstantiation, that central moment when the unleavened bread and wine were transformed into the Body and Blood of Christ and, then, elevated them in the sight of the Apostles, who represented the whole Church, Hierarchy and faithful.

The New Testament clearly reflects the origin of the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass in written accounts of the Last Supper (Matt 26:26-28, Mark 14:23-24, Lk 23:19-20, Cor 11:23-25). Sacred Tradition and the Extraordinary Magisterium clearly substantiated Sacred Scripture.

Importantly, Our Lord said at the Last Supper in Aramaic the words “Mystery of Faith” or Mysterium Fidei, in Latin. This formula was always used in the Tridentine Mass, but was removed from the ICEL Novus Ordo Missae. Mysterium Fidei is the heart of the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass, the Transubstantiation. The absence of this formula was gladly accepted by the Protestants, interpreted by them as a denial of the Real Presence. (2)

Also, many modern liturgists deny that the first Mass occurred on Holy Thursday, a position that repeats exactly that taken at the time of the Protestant Revolution. The Protestants consider the first Mass to be on Good Friday, thus turning the ‘eucharistic supper’ of Holy Thursday into nothing more than a commemorative meal. This is also a position that was adopted by progressivists in the New Mass, which abolished the sacrificial character of the Mass and give emphasis to it as a memorial supper.

An unbloody Sacrifice

At the last Supper on Holy Thursday, Our Lord Jesus Christ instituted the visible unbloody sacrifice of the Mass in order to represent the bloody sacrifice that He would offer on Good Friday on the Cross, where all of His Blood was shed for the redemption of mankind until the end of the world. The setting for the first Mass was significant: the paschal lamb meal that the Jews celebrated every year was to recall the exodus from Egypt and to prefigure the great expectation of the Redemption.

The sacrifice of Moses prefigured

the Passion and Death of Our Lord

The sacrifice of Moses was a prelude of Our Lord's Passion and Death. Jesus Christ desired that His Passion and Death should follow immediately after the Last Supper, signifying that they were one and the same act. The sacrifice in the Holy Mass begins at the consecration of the bread and wine into the Body, Blood, Soul and Divinity of Our Lord, the Transubstantiation, which is the very heart of the Mass.

According to the Venerable Mary of Agreda in The Mystical City of God, the Infant Jesus was transfixed after the Angel Gabriel placed Him in the arms of Our Lady. He revealed to His Mother the details of the Last Supper, His Passion and Death, and the sword of sorrow that would pierce her heart. Seven days after the Nativity at the Circumcision, He shed the first drops of His Precious Blood – enough to redeem mankind according to Ven Mary of Agreda. But, by the Divine Plan He was to shed all of His Precious Blood for our redemption.

At the Last Supper Our Lord transmitted to the Apostles the power to transubstantiate with the words: “Do this in memory of Me,” and all priestly successors also have this miraculous power (Council of Trent 22, 1).

The first Sacramentaries

In the first three centuries, Greek was the liturgical language at Rome and the names used for the whole sacrifice of the Mass were Eucharistia, or Eucharist, translated from Greek to Latin it is Divina Sacrificia or Divine Sacrifice, and Sacrificia Dei meaning Sacrifice of God.

In the year 88, the fourth Pope, St. Clement of Rome, martyr, wrote in his letter to the Corinthinians that Our Lord laid down the order of the Mass, referring specifically to the Offertory, Consecration and Communion. St. Clement made it clear this order was established by Christ: "We must do all things that the Lord told us to do at stated times” (Chapter xi). (3)

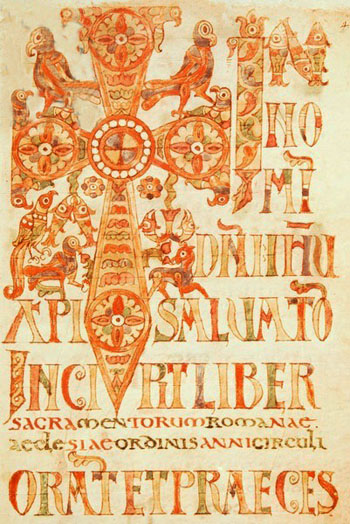

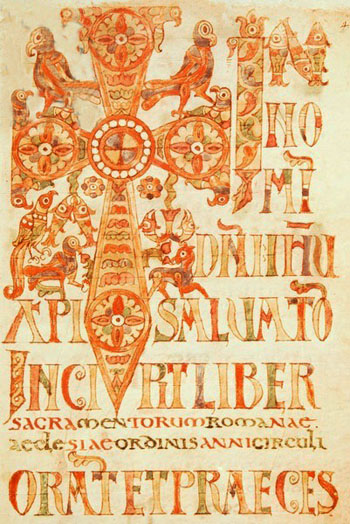

The frontipiece of a Gelasian Sacramentary

dating from the 8th century

In the second century, St. Justin, martyr, wrote that after His Resurrection, Our Lord taught the Apostles how to say the Mass. St. Justin gave an open and complete account of the whole service and of its meaning, attributing the rite to Our Lord's institution as contained in the Gospels. (5)

It is generally held that the writings of St. Clement and St. Justin were formally expressed by St. Ambrose circa 387 AD in a book entitled De Sacramentis, which reiterated that the essential parts of the Mass are the Offertory, the Consecration and the Communion and was undertaken to form a uniform, unchanging Canon. It was in this century that Latin became the official language of the Church and the word Missa was introduced by St. Ambrose. To this day the Eastern Rites use the word Liturgia for the Holy Sacrifice.

The Leonine Sacramentary by Pope Leo the Great in the year 450, the essential parts of the Mass were the same as the form found in the Tridentine Mass. The Gelasian Sacramentary of Pope Gelasius I in 496 made the same order and formulae even clearer. There we find the same Canon as we had until Vatican II.

During the very important reign of Pope Gregory I, known as Gregory the Great, at the end of the 6th century (590-604), the finishing touches of the Mass were put on his Gregorian Sacramentary, which is essentially the same Mass codified by the Council of Trent (1545-1563), 10 centuries later, for the Ordinary of the Mass. The Mass Propers, the scriptural texts that change daily with the liturgical calendar, of course had many additions over the years.

From this history, summarily presented here, there is one important fact to be stated by Fr. Adrian Fortescue in his landmark study on the Mass, and underscored by us: “From roughly the time of St. Gregory [d. 604] we have the text of the Mass, its order and arrangement, as a sacred tradition that no one has ventured to touch except in unimportant details."

This statement was true until Vatican Council II.

Continued

- Francis Spirago, The Catechism Explained, ed by Richard F. Clarke, New York: Benzinger Bros, 1899; reprinted by TAN books in 1993, p. 532

- The commission appointed by Paul VI to write the New Ordinary of the Mass, as well as the translation of it proposed for the English speaking world by the ICEL and adopted by the American Bishops, were responsible for this new formula. That commission was headed by the radical progressivist Fr. Annibale Bugnini, a supposed Freemason, and included six Protestants. Fr. Bugnini stated that his aim in designing the New Mass was “to strip from our Catholic prayers and from the Catholic liturgy everything which can be the shadow of a stumbling block for our separated brethren, that is, for the Protestants.” (L'Osservatore Romano, March 19, 1965)

- Adrian Fortescue, The Mass: A Study of the Roman Liturgy, London, New York: Longmans, Green. 1912, pp. 11-12.

- Ibid.

- Ibid., pp. 2, 21-22

- Ibid., pp. . 128, 149-150, 213

- Ibid., pp. 111, 117,138

- Catholic Encyclopedia, entry Liturgical Books, New Advent online edition.

- A. Fortescue, The Mass: A Study of the Roman Liturgy, p. 173

Posted November 14, 2014