Symbolism

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Knowing the Saints by their Emblems

In spite of all their endeavors, all their impassioned desire to represent clear-cut personality, the 13th century artists could not contrive that men should unhesitatingly recognize the name of each of his statues representing saints. How would it be possible to prevent the confusion of two saintly knights – St. George and St. Theodore – or two maidens – St. Barbara and St. Agnes? In the 13th century men still sought the solution to the problem.

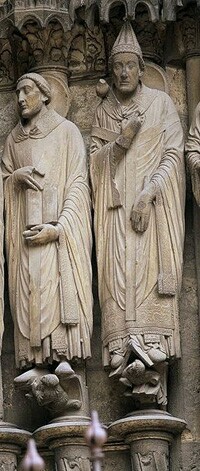

At Chartres it was solved in an ingenious way. A little scene which recalled some famous episode in the life or death of the saint was placed beneath his feet. For example, beneath the bracket on which stood the statue of St. Denis was carved one of the lions to which the martyr was exposed. Beneath the bracket of St. George’s statue, a wheel which recalled the manner of his death was sculpted. Above the instruments of their torture or above their persecutors stand the saints in triumph.

At Chartres it was solved in an ingenious way. A little scene which recalled some famous episode in the life or death of the saint was placed beneath his feet. For example, beneath the bracket on which stood the statue of St. Denis was carved one of the lions to which the martyr was exposed. Beneath the bracket of St. George’s statue, a wheel which recalled the manner of his death was sculpted. Above the instruments of their torture or above their persecutors stand the saints in triumph.

But the artists wished to arrest the attention still more completely, and they began to place the instrument of torture in the hand of the saint. First the Apostles appeared in the cathedral porches carrying the cross on which they had been fastened, the lance or the sword with which they had been pierced, the knife with which their bodies had been gashed. From the 14th century almost all the saints are represented holding a special attribute.

In the Portail des Libraires at Rouen St. Apollina holds the pincers with which her teeth had been drawn. St. Barbara holds the tower with the three windows (symbol of the Trinity) in which she had been imprisoned by her father. Proud and triumphant, the saints bear the instruments of torture that had opened to them the gate of Heaven.

Sometimes the attribute was furnished by some famous episode in the life of a saint. St. John is recognized by the cup surmounted by a serpent, for it recalls that after making the sign of the cross, the Apostle drank a poisoned cup unharmed. The little winged dragon often seen on the cup symbolizes the strength of the poison.

Sometimes the attribute was furnished by some famous episode in the life of a saint. St. John is recognized by the cup surmounted by a serpent, for it recalls that after making the sign of the cross, the Apostle drank a poisoned cup unharmed. The little winged dragon often seen on the cup symbolizes the strength of the poison.

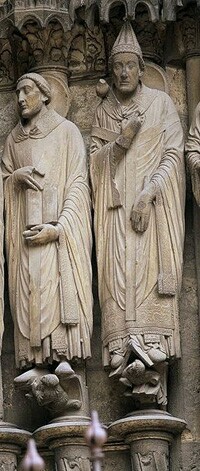

St. Gregory the Great is distinguished among other

Popes by the dove on his shoulder. For it was said that the dove dictated his books to him, and hidden behind a curtain his secretary one day saw it whispering in his ear.

St. Mary of Egypt cannot be confused with any other penitent, for she carries the three loaves of bread that she bought before retiring to the desert and on which she was nourished for 40 years.

Where does St. Genevieve’s candle come from if not from a metaphor? The saint holds the flame of the Wise Virgins, the symbolic lamp spoken of in the Gospel. Unless guarded by an Angel, a breath of the evil spirit might well extinguish that flickering light.

An illustration used in sermons because the scene full of humor found in the porch of Notre Dame at Paris, where on one side the Devil blows out the Saint’s candle, on the other side an Angel re-lights it. The mystical simile of the lamp of the Wise Virgins was also used in Flanders, where St. Gudule is seen on the seal of the chapter of Brussels carrying her lantern between the Devil and an Angel.

Closely connected with men’s daily life, the saints at times received strange attributes in popular art. St. Martin, for example, is sometimes represented accompanied by a wild goose. No incident in his history justifies this emblem. The goose is in fact intended as a reminder that the feast of St. Martin at the beginning of winter coincides with the migration of the birds.

Thus was the whole life of the Saint gathered up in one distinctive feature. Such was the people’s familiarity with these attributes that they were never mistaken in their reading of the saints in the porches and windows.

Continued

St. Denis, left, has a lion under his feet; St. Georges, right, is represented attached to a wheel - Chartres

But the artists wished to arrest the attention still more completely, and they began to place the instrument of torture in the hand of the saint. First the Apostles appeared in the cathedral porches carrying the cross on which they had been fastened, the lance or the sword with which they had been pierced, the knife with which their bodies had been gashed. From the 14th century almost all the saints are represented holding a special attribute.

In the Portail des Libraires at Rouen St. Apollina holds the pincers with which her teeth had been drawn. St. Barbara holds the tower with the three windows (symbol of the Trinity) in which she had been imprisoned by her father. Proud and triumphant, the saints bear the instruments of torture that had opened to them the gate of Heaven.

St. Jerome, left, holds the Bible he translated; St. Gregory has a dove on his shoulder - Chartres

St. Gregory the Great is distinguished among other

Popes by the dove on his shoulder. For it was said that the dove dictated his books to him, and hidden behind a curtain his secretary one day saw it whispering in his ear.

St. Mary of Egypt cannot be confused with any other penitent, for she carries the three loaves of bread that she bought before retiring to the desert and on which she was nourished for 40 years.

Where does St. Genevieve’s candle come from if not from a metaphor? The saint holds the flame of the Wise Virgins, the symbolic lamp spoken of in the Gospel. Unless guarded by an Angel, a breath of the evil spirit might well extinguish that flickering light.

An illustration used in sermons because the scene full of humor found in the porch of Notre Dame at Paris, where on one side the Devil blows out the Saint’s candle, on the other side an Angel re-lights it. The mystical simile of the lamp of the Wise Virgins was also used in Flanders, where St. Gudule is seen on the seal of the chapter of Brussels carrying her lantern between the Devil and an Angel.

Closely connected with men’s daily life, the saints at times received strange attributes in popular art. St. Martin, for example, is sometimes represented accompanied by a wild goose. No incident in his history justifies this emblem. The goose is in fact intended as a reminder that the feast of St. Martin at the beginning of winter coincides with the migration of the birds.

Thus was the whole life of the Saint gathered up in one distinctive feature. Such was the people’s familiarity with these attributes that they were never mistaken in their reading of the saints in the porches and windows.

Continued

Selected from Emile Mâle,

The Gothic Image: Religious Art in France of the 13th Century.

NY: Harper & Brothers, pp 285-286.

Posted August 16, 2014

The Gothic Image: Religious Art in France of the 13th Century.

NY: Harper & Brothers, pp 285-286.

Posted August 16, 2014

______________________

______________________