|

Symbolism

The Man, The Ox, The Lion & The Eagle

Marian Therese Horvat, Ph.D.

The Age of Faith was well named, for during that happy age, the Faith influenced everything, even the way of thinking of men in the presence of nature. Not only the learned medieval doctors but also the simple peasant people knew how to find the rich symbolic meanings of the created world. When Hugh of St. Victor, the great doctor of the Victorine School of Theology, saw a dove, he thought of the Church, for the dove has two wings even as the Christian has two ways of life – the active and the contemplative. The blue sheen of the wings represents thoughts of heaven. Its yellow eyes are the looks full of wisdom that the Church casts on the future. Its red feet reveal how the Church touches the world with her feet in the blood of the martyrs.

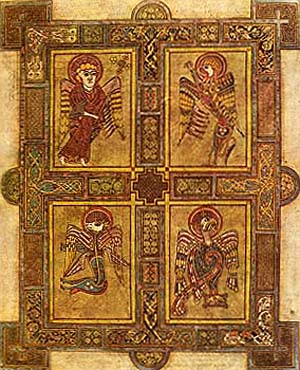

The man, the ox, the lion and the eagle represent the four Apostles who wrote the Books of the New Testament, Matthew, Mark, Luke and John - Book of Kells |

When the simple peasants contemplated the shortening days of winter and what seems to be the triumph of darkness over light, they thought of the long centuries of twilight that preceded the coming of Christ, and they understood that in the divine drama both light and darkness have a place. It was at the winter solstice, when the light begins to reappear and the days to lengthen, that the Son of God was born.

Most certainly this is not a kind of primitive “superstitious thinking” of the poor men of the Dark Ages, unenlightened by the scientific method and unburdened by statistical evidence. No, suave and subtle interpretations like these date back to the early days of the Church. In their writings, the Church Fathers saw the material world as a constant image of the spiritual world: even the images of nature in Scriptures were interpreted in this light. The juniper tree and the snow-capped mountains of Lebanon are the thoughts of God. The roses in Ecclesiasticus signify the blood of martyrs and the nettles represent the evil that chokes the good.

Four of the best-known animal forms still familiar to us today are the four beasts of the Gospels. From earliest Christian times, the man, the eagle, the lion and the ox, first seen in Ezekiel’s vision by the river Chebar and later by St. John surrounding the throne of God, have been accepted as the symbols of the four evangelists. The man symbolized St. Matthew, because his Gospel begins by stating the genealogy of the ancestors of Christ. The lion is St. Mark, who early in his Gospel speaks of a voice crying in the wilderness. The ox, the sacrificial animal of the Old Covenant, symbolizes St. Luke, whose Gospel opens with the sacrifice offered by Zacharias. The eagle, believed to be the only animal that could gaze straight into the light of the sun, is St. John, who in his Gospel soars into the mystery of the Incarnation of God so naturally and contemplates it so profoundly that he seems like an eagle flying toward the sun.

By the twelfth century, the medieval doctors of the Church had enlarged upon the symbolism of the four beasts to also recall the major events in the life of Christ. The man is the reminder that God became man in the Incarnation. The ox recalls the sacrificial victim of the New Law, Our Lord Jesus Christ and His Passion. The lion, a symbol of vigilance because it was believed to sleep with its eyes open, symbolized the Resurrection when Our Lord appeared to sleep in death, even though His divine nature never dies and remains watching. Finally, as the eagle rises to the unknown heights, Christ rose to Heaven in the Ascension.

But there was yet a third meaning and teaching in the four beasts, which also showed man the virtues he must practice. Every pilgrim on his arduous journey through life to heaven must be a man, because God gave to man alone the gift of reason, which he must use to achieve heaven. He must also be an ox, the sacrificial victim, because it is necessary to make penance and mortify the flesh. He must be the lion in his courage and noble hearted deeds. And he must pray and contemplate God and the things of eternity like the eagle, which looks straight into the sun.

This is the Church’s marvelous symbolism on the four animals, although only the one that likens the beasts to the Evangelists survived medieval times. The others fell into oblivion during the Protestant Revolution, which stripped so much of the rich and mystical meaning from Catholic symbols. One of the first things the Philistines did when they caught Samson was to put out his eyes. So it seems that, in an age that began to reverence cold facts and hard statistics, the devil contrived to blind the man of Faith to the more profound meanings of the created world. This is why this kind of meditation is of such great value – truly it opens the eyes to find and see God in the created world.

Someone might say, “But what about the ecological movement? Doesn’t it include a return to an appreciation of the values of nature and a kind of restoration of this kind of medieval thinking?

I often think that the “return to nature” movement of the ‘60s that gave birth to today’s ecological movement was a comprehensible, although not justifiable, reaction to the type of cold positivism that could reduce the Niagara Falls only to frigid statistics, instead of a symbol of the power and magnificence of God. It is a comprehensible reaction because it is true that the industrial revolution did not put a high priority on the working conditions for man or the harm to nature, and this is really a bad thing. But it is not a justifiable reaction, because the ideas of the ecological revolution cloak a philosophy that is an even worse thing. As part of its agenda to protect animals and nature, the ecological movement returns to the erroneous pantheist idea that every living creature – man, animal and plant – has the right to exist because God would be immanent in the essence of everything.

This is the deeper side of the ecologist philosophy, and from it comes the tendency of Western man to embrace Buddhism, the latest fad among considerable segments of today’s youth as well as artistic and upper society circles in Europe and the United States. It is not difficult to see that both the ecologist philosophy and the Buddhist religion are heading toward a new paganism, which means the denial of the Catholic Faith.

Thus, the symbolic teaching of the Middle Ages has all the more need to be recalled and restored, to provide a healthy Catholic alternative to the immanentist and pantheist errors of the ecological revolution. The images of the man, the ox, the lion and the eagle, for example, become a catechism class, charming in its simplicity and imagery. For those readers who share my interest in this kind of meditation, let me suggest a helpful book that has been translated from French to English and describes the rich symbolism of the figures and motifs of the cathedrals of the Middle Ages: The Gothic Image: Religious Art in France of the Thirteenth Century by Emile Mâle. It is available in paperback from Dover Books.

|

Symbolism | Religious | Home | Books | CDs | Search | Contact Us | Donate

© 2002-

Tradition in Action, Inc. All Rights Reserved

|

|

|