Catholic Customs

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The ‘Boy Bishops’ of Holy Innocents Day

Icon from the Chapel of the Holy Innocents, Bethlehem

And grievously bewilder

So he gave the word to slay

And slew the little childer

And slew the little childer.

(15th century, tr. G. R. Woodward)

White pudding with red sauce

honoring the Holy Innocents

The moving sentiments that filled the souls of our Catholic forbearers inspired them to give special attention to children on this feast by allotting them special privileges.

In monasteries and convents, the youngest members of the monastery were treated with special regard and were served a type of "infant food" at the evening meal. This dish was either a hot porridge sweetened with sugar and cinnamon or a light-colored pudding covered with a red sauce to honor the purity and the blood of the Holy Innocents. (1)

The boy-bishops

In Medieval monastery schools, cathedrals, parish churches and the chapels of nobles, the choir or altar boys elected a boy-bishop (Episcopus Puerorum) who took charge of the abbey or cathedral for the whole day on Holy Innocents Day. This custom is believed to have originated in Germany where, by the 10th century, the tradition was established of allowing the lower clergy to take charge on chosen days.

A boy bishop processes through

the streets of Bamburg, Germany

The eve of St. Nicholas' Day (December 5) became the traditional day for electing the bishops who held their “office” until Holy Innocents' Day, when they performed their main ceremonial duties. (3)

Adorned in pontifical vestments proper to his "office," the boy-bishop performed all of the duties of the normal clergy except that of saying the Mass. He led processions, presided at vespers, gave benedictions, delivered sermons and sometimes conducted a visitation. During the boy-bishop's "reign," several choir boys were selected to form his chapter of "canons," and the group was often referred to as "Nicholas and his clerks." (4)

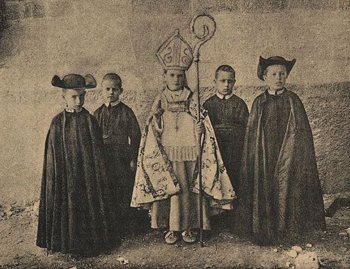

Boy bishops in Montserrat, Spain

Beginning at vespers on December 27, the boy-bishop and his "canons" would sit in the stalls of the upper canons, while the latter performed the usual roles of the boys as acolytes, thurifers, and lower clerks. Finally, on the feast of the Holy Innocents the boy-bishop delivered a sermon that had been written by a distinguished Prelate. As his clear voice resonated through the cathedral, the people were drawn to praise God who has perfected praise “out of the mouth of infants and of sucklings.” (Ps 8:2).

This reversal of roles was performed very respectfully, with attention to the dignity of the ecclesiastical state. Always under the guidance and authority of the clergy, the boy-bishops were expected to be well-behaved and to take their role seriously as representatives of Princes of the Church.

So serious were the privileges given to the boy-bishops that even the royalty respected them. On December 7 in the year 1299, King Edward I of England permitted a boy-bishop with his "canons" to sing vespers for him in his chapel at Hetton. (6)

Imitating this practice, many monasteries and convents allowed the young members of the novitiate to rule for the day. In Franciscan monasteries, one young monk was elected to be the "Innocent" whose role was to take the Abbot's place by presiding at the prayers and preaching a sermon. (7)

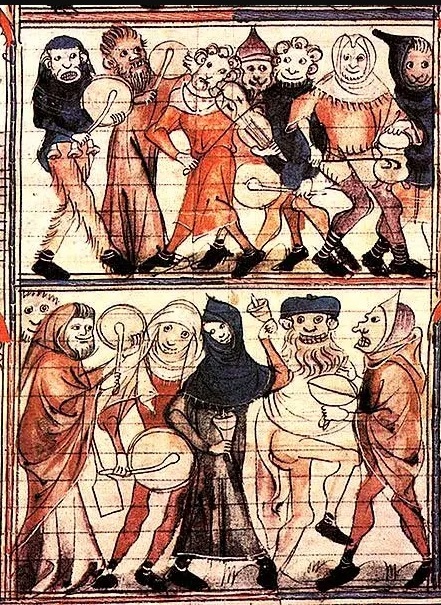

Medieval depiction of the ‘feast of fools’

Spain and the countries it influenced (Belgium, Latin America, Philippines) celebrated this feast as a Fool's Day with the traditional jokes and pranks. Mock monarchs or mayors were often elected, while masqueraders went through the streets making mischief. The Pranksters were called inocentadas and their victims received the name of inocentes.

Many of these customs are still preserved today. People from Yeste are expected to pay a fine to the masqueraders (calentureros) who appear with elaborate masks and whips to pursue those who obstinately refuse to pay. In Catalonia, a mock mayor is chosen whose chief task is to force the people to clean the streets. While the mayor rules, fires are lit in the town gate ways and any visitor entering the city is required to pay a toll. (8)

Lamentation for Rachel who bewails her children

Joyous merriment is accompanied by a somber spirit of mourning on this important Feast. For, while the Innocents rejoiced in their newfound glory, their mothers mourned and wept for the loss of their dear ones.

In the past in England, this day was called “Cross day” and the bells were rung in muffled tones. In the village of Norton in Worcestershire, the sorrow and joy of the day were united in the pealing of the bells that were first muffled as a sign of mourning, and then made to peal forth joyous tones to celebrate the deliverance of the Christ Child. (9)

Mothers grieve at the slaying of their children

The horror of the slaughter caused many medieval people of England and France to consider this a very unlucky day. According to the old lore, any new undertaking begun on this day would never reach fulfillment. Likewise, there was an ill omen for any man who worked, got married, washed or wore new clothes on this day.

So seriously was this lore taken, that in 1460 when Edward IV's coronation fell on Childermass, it was postponed to the next day. Workers in dangerous occupations (fisherman, miners, etc) often refused to work on this day. The Northumberland lead-miners upheld this conviction even up until the mid 1800s. (11)

Despite the sorrow that this feast brings, the joy of Christ’s birth and the victory of the Holy Innocents triumphs in the spirit of our Holy Mother the Church who, while a mother to the dear martyrs is yet the child of Him Whose birth dispels all sadness. With Our Mother, we ought to pay due homage to the “flowers of the Martyrs” by honoring in some way Catholic children, who by their baptism are living temples of the Most Holy Trinity and mirrors of the babes slain by Herod’s cruel hand.

- Evelyn Birge Vitz, A Continual Feast (San Fransisco: Ignatius Press, 1985), p. 158.

- Cristina Garcia Rodero, Festivals and Rituals of Spain (New York: Harry N. Abrams Inc, 1994), p. 31.

- Steve Roud, The English Year (Penguin Books: 2006), p. 362.

- William S. Walsh, Curiosities of Popular Customs and of Rites, Ceremonies, Observances, and Miscellaneous Antiquities (Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott Company, 1898), p. 145.

- https://www.liturgicalartsjournal.com/2021/01/customs-and-traditions-boy-bishop.html

- W. S. Walsh, Curiosities of Popular Customs, p. 145.

- Joanna Bogle, A Book of Feasts and Seasons (Herefordshire, England: Gracewing, 1992), p. 59.

- Violet Alford, Pyrenean Festivals: Calendar Customs, Magic and Music, Drama and Dance (London: Chatto and Windus, 1937), p. 15.

- W. S. Walsh, Curiosities of Popular Customs, p. 553.

- https://www.thebookofdays.com/months/dec/28.htm

- Bonnie Blackburn and Leofranc Holford-Strevens, The Oxford Companion to the Year (New York: Oxford University Press, 1999), p. 538.

Posted January 2, 2023

______________________

______________________

|

|

|

|

|

|